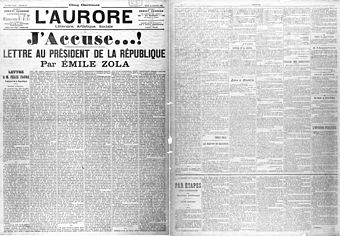

Translation:J'Accuse...!

I Accuse...!

LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC

By ÉMILE ZOLA

Letter to Mr. Félix Faure,

President of the Republic

Would you allow me, in my gratitude for the benevolent reception that you gave me one day, to draw the attention of your rightful glory and to tell you that your star, so happy until now, is threatened by the most shameful and most ineffaceable of blemishes?

You have passed healthy and safe through base calumnies; you have conquered hearts. You appear radiant in the apotheosis of this patriotic festival that the Russian alliance was for France, and you prepare to preside over the solemn triumph of our World Fair, which will crown our great century of work, truth and freedom. But what a spot of mud on your name—I was going to say on your reign—is this abominable Dreyfus affair! A council of war, under order, has just dared to acquit Esterhazy, a great blow to all truth, all justice. And it is finished, France has this stain on her cheek, History will write that it was under your presidency that such a social crime could be committed.

Since they dared, I too will dare. The truth I will say, because I promised to say it, if justice, regularly seized, did not do it, full and whole. My duty is to speak, I do not want to be an accomplice. My nights would be haunted by the specter of innocence that suffer there, through the most dreadful of tortures, for a crime it did not commit.

And it is to you, Mr. President, that I will proclaim it, this truth, with all the force of the revulsion of an honest man. For your honour, I am convinced that you are unaware of it. And with whom will I thus denounce the criminal foundation of these guilty truths, if not with you, the first magistrate of the country?

First, the truth about the lawsuit and the judgment of Dreyfus.

A nefarious man carried it all out, did everything: Lieutenant Colonel Du Paty de Clam, at that time only a Commandant. He is the entirety of the Dreyfus business; it will be known only when one honest investigation clearly establishes his acts and responsibilities. He seems a most complicated and hazy spirit, haunting romantic intrigues, caught up in serialised stories, stolen papers, anonymous letters, appointments in deserted places, mysterious women who sell condemning evidences at night. It is he who imagined dictating the Dreyfus memo; it is he who dreamed to study it in an entirely hidden way, under ice; it is him whom commander Forzinetti describes to us as armed with a dark lantern, wanting to approach the sleeping defendant, to flood his face abruptly with light and to thus surprise his crime, in the agitation of being roused. And I need hardly say that that what one seeks, one will find. I declare simply that commander Du Paty de Clam, charged to investigate the Dreyfus business as a legal officer, is, in date and in responsibility, the first culprit in the appalling miscarriage of justice committed.

The memo was for some time already in the hands of Colonel Sandherr, director of the office of information, who has since died of general paresis. "Escapes" took place, papers disappeared, as they still do today; the author of the memo was sought, when ahead of time one was made aware, little by little, that this author could be only an officer of the High Comman and an artillery officer: a doubly glaring error, showing with which superficial spirit this affair had been studied, because a reasoned examination shows that it could only be a question of an officer of troops. Thus searching the house, examining writings, it was like a family matter, a traitor to be surprised in the same offices, in order to expel him. And, while I do not want to retell a partly known history here, Commander Paty de Clam enters the scene, as soon as first suspicion falls upon Dreyfus. From this moment, it is he who invented Dreyfus, the affair becomes that affair, made actively to confuse the traitor, to bring him to a full confession. There is the Minister of War, General Mercier, whose intelligence seems poor; there are the head of the High Command, General De Boisdeffre, who appears to have yielded to his clerical passion, and the assistant manager of the High Command, General Gonse, whose conscience could put up with many things. But, at the bottom, there is initially only Commander Du Paty de Clam, who carries them all out, who hypnotizes them, because he deals also with spiritism, with occultism, conversing with spirits. One could not conceive of the experiments to which he subjected unhappy Dreyfus, the traps into which he wanted to make him fall, the insane investigations, monstrous imaginations, a whole torturing insanity.

Ah! this first affair is a nightmare for those who know its true details! Commander Du Paty de Clam arrests Dreyfus, in secret. He turns to Mrs. Dreyfus, terrorises her, says to her that, if she speaks, her husband is lost. During this time, the unhappy one tore his flesh, howled his innocence. And the instructions were made thus, as in a 15th century tale, shrouded in mystery, with a savage complication of circumstances, all based on only one childish charge, this idiotic affair, which was not only a vulgar treason, but was also the most impudent of hoaxes, because the famously delivered secrets were almost all without value. If I insist, it is that the kernel is here, from whence the true crime will later emerge, the terrible denial of justice from which France is sick. I would like to touch with a finger on how this miscarriage of justice could be possible, how it was born from the machinations of Commander Du Paty de Clam, how General Mercier, General De Boisdeffre and General Gonse could be let it happen, to engage little by little their responsibility in this error, that they believed a need, later, to impose like the holy truth, a truth which is not even discussed. At the beginning, there is not this, on their part, this incuriosity and obtuseness. At most, one feels them to yield to an ambiance of religious passions and the prejudices of the physical spirit. They allowed themselves a mistake.

But here Dreyfus is before the council of war. Closed doors are absolutely required. A traitor would have opened the border with the enemy to lead the German emperor to Notre-Dame, without taking measures to maintain narrow silence and mystery. The nation is struck into a stupor, whispering of terrible facts, monstrous treasons which make History indignant; naturally the nation is so inclined. There is no punishment too severe, it will applaud public degradation, it will want the culprit to remain on his rock of infamy, devoured by remorse. Is this then true, the inexpressible things, the dangerous things, capable of plunging Europe into flames, which one must carefully bury behind these closed doors? No! There was behind this, only the romantic and lunatic imaginations of Commander Paty de Clam. All that was done only to hide the most absurd of novella plots. And it suffices, to ensure oneself of this, to study with attention the bill of indictment, read in front of the council of war.

Ah! the nothingness of this bill of indictment! That a man could be condemned for this act, is a wonder of iniquity. I defy decent people to read it, without their hearts leaping in indignation and shouting their revolt, while thinking of the unwarranted suffering, over there, on Devil's Island. Dreyfus knows several languages, crime; one found at his place no compromising papers, crime; he returns sometimes to his country of origin, crime; he is industrious, he wants to know everything, crime; he is unperturbed, crime; he is perturbed, crime. And the naiveté of drafting formal assertions in a vacuum! One spoke to us of fourteen charges: we find only one in the final analysis, that of the memo; and we even learn that the experts did not agree, than one of them, Mr. Gobert, was coerced militarily, because he did not allow himself to reach a conclusion in the desired direction. One also spoke of twenty-three officers who had come to overpower Dreyfus with their testimonies. We remain unaware of their interrogations, but it is certain that they did not all charge him; and it is to be noticed, moreover, that all belonged to the war offices. It is a family lawsuit, one is there against oneself, and it is necessary to remember this: the High Command wanted the lawsuit, it was judged, and it has just judged it a second time.

Therefore, there remained only the memo, on which the experts had not concurred. It is reported that, in the room of the council, the judges were naturally going to acquit. And consequently, as one includes/understands the despaired obstinacy with which, to justify the judgment, today the existence of a secret part is affirmed, overpowering, the part which cannot be shown, which legitimates all, in front of which we must incline ourselves, the good invisible and unknowable God! I deny it, this part, I deny it with all my strength! A ridiculous part, yes, perhaps the part wherein it is a question of young women, and where a certain D… is spoken of which becomes too demanding: some husband undoubtedly finding that his wife did not pay him dearly enough. But a part interesting the national defense, which one could not produce without war being declared tomorrow, no, no! It is a lie! and it is all the more odious and cynical that they lie with impunity without one being able to convince others of it. They assemble France, they hide behind its legitimate emotion, they close mouths by disturbing hearts, by perverting spirits. I do not know a greater civic crime.

Here then, Mr. President, are the facts which explain how a miscarriage of justice could be made; and the moral evidence, the financial circumstances of Dreyfus, the absence of reason, his continual cry of innocence, completes its demonstration as a victim of the extraordinary imaginations of commander Du Paty de Clam, of the clerical medium in which it was found, of the hunting for the "dirty Jews", which dishonours our time.

And we arrive at the Esterhazy affair. Three years passed, many consciences remain deeply disturbed, worry, seek, end up being convinced of Dreyfus's innocence.

I will not give the history of the doubts and of the conviction of Mr. Scheurer-Kestner. But, while this was excavated on the side, it ignored serious events among the High Command. Colonel Sandherr was dead, and Major Picquart succeeded him as head of the office of the information. And it was for this reason, in the performance of his duties, that the latter one day found in his hands a letter-telegram, addressed to commander Esterhazy, from an agent of a foreign power. His strict duty was to open an investigation. It is certain that he never acted apart from the will of his superiors. He thus submitted his suspicions to his seniors in rank, General Gonse, then General De Boisdeffre, then General Billot, who had succeeded General Mercier as the Minister of War. The infamous Picquart file, about which so much was said, was never more than a Billot file, a file made by a subordinate for his minister, a file which must still exist within the Ministry of War. Investigations ran from May to September 1896, and what should be well affirmed is that General Gonse was convinced of Esterhazy's guilt, and that Generals De Boisdeffre and Billot did not question that the memo was written by Esterhazy. Major Picquart's investigation had led to this unquestionable observation. But the agitation was large, because the condemnation of Esterhazy inevitably involved the revision of Dreyfus's trial; and this, the High Command did not want at any cost.

There must have been a minute full of psychological anguish. Notice that General Billot was in no way compromised, he arrived completely fresh, he could decide the truth. He did not dare, undoubtedly in fear of public opinion, certainly also in fear of betraying all the High Command, General De Boisdeffre, General Gonse, not mentioning those of lower rank. Therefore there was only one minute of conflict between his conscience and what he believed to be the military's interest. Once this minute had passed, it was already too late. He had engaged, he was compromised. And, since then, his responsibility only grew, he took responsibility for the crimes of others, he became as guilty as the others, he was guiltier than them, because he was the Master of justice, and he did nothing. Understand that! Here for a year General Billot, General De Boisdeffre and General Gonse have known that Dreyfus is innocent, and they kept this appalling thing to themselves! And these people sleep at night, and they have women and children whom they love!

Major Picquart had fulfilled his duty as an honest man. He insisted to his superiors, in the name of justice. He even begged them, he said to them how much their times were ill-advised, in front of the terrible storm which was to pour down, which was to burst, when the truth would be known. It was, later, the language that Mr. Scheurer-Kestner also used with General Billot, entreating him with patriotism to take the affair in hand, not to let it worsen, on the verge of becoming a public disaster. No! The crime had been committed, the High Command could no longer acknowledge its crime. And Major Picquart was sent on a mission, one that took him farther and farther away, as far as Tunisia, where there was not even a day to honour his bravery, charged with a mission which would have surely ended in massacre, in the frontiers where Marquis de Morès met his death. He was not in disgrace, General Gonse maintained a friendly correspondence with him. It is only about secrets he was not good to have discovered.

To Paris, the truth inexorably marched, and it is known how the awaited storm burst. Mr. Mathieu Dreyfus denounced commander Esterhazy as the true author of the memo just as Mr. Scheurer-Kestner demanded a revision of the case to the Minister of Justice. And it is here that commander Esterhazy appears. Testimony shows him initially thrown into a panic, ready for suicide or escape. Then, at a blow, he acted with audacity, astonishing Paris by the violence of his attitude. It is then that help had come to him, he had received an anonymous letter informing him of the work of his enemies, a mysterious lady had come under cover of night to return a stolen evidence against him to the High Command, which would save him. And I cannot help but find Major Paty de Clam here, considering his fertile imagination. His work, Dreyfus's culpability, was in danger, and he surely wanted to defend his work. The retrial was the collapse of such an extravagant novella, so tragic, whose abominable outcome takes place in Devil's Island! This is what he could not allow. Consequently, a duel would take place between Major Picquart and Major Du Paty de Clam, one with face uncovered, the other masked. They will soon both be found before civil justice. In the end, it was always the High Command that defended itself, that did not want to acknowledge its crime; the abomination grew hour by hour.

One wondered with astonishment who were protecting commander Esterhazy. It was initially, in the shadows, Major Du Paty de Clam who conspired all and conducted all. His hand was betrayed by its absurd means. Then, it was General De Boisdeffre, it was General Gonse, it was General Billot himself, who were obliged to discharge the commander, since they cannot allow recognition of Dreyfus's innocence without the department of war collapsing under public contempt. And the beautiful result of this extraordinary situation is that the honest man there, Major Picquart, who only did his duty, became the victim of ridicule and punishment. O justice, what dreadful despair grips the heart! One might just as well say that he was the forger, that he manufactured the carte-télegramme to convict Esterhazy. But, good God! why? with what aim? give a motive. Is he also paid by the Jews? The joke of the story is that he was in fact an anti-Semite. Yes! we attend this infamous spectacle, of the lost men of debts and crimes upon whom one proclaims innocence, while one attacks honor, a man with a spotless life! When a society does this, it falls into decay.

Here is thus, Mr. President, the Esterhazy affair: a culprit whose name it was a question of clearing. For almost two months, we have been able to follow hour by hour the beautiful work. I abbreviate, because it is not here that a summary of the history's extensive pages will one day be written out in full. We thus saw General De Pellieux, then the commander of Ravary, lead an investigation in which the rascals are transfigured and decent people are dirtied. Then, the council of war was convened.

How could one hope that a council of war would demolish what a council of war had done?

I do not even mention the always possible choice of judges. Isn't the higher idea of discipline, which is in the blood of these soldiers, enough to cancel their capacity for equity? Who says discipline breeds obedience? When the Minister of War, the overall chief, established publicly, with the acclamations of the national representation, the authority of the final decision; you want a council of war to give him a formal denial? Hierarchically, that is impossible. General Billot influenced the judges by his declaration, and they judged as they must under fire, without reasoning. The preconceived opinion that they brought to their seats, is obviously this one: "Dreyfus was condemned for crime of treason by a council of war, he is thus guilty; and we, a council of war, cannot declare him innocent, for we know that to recognize Esterhazy's guilt would be to proclaim the innocence of Dreyfus." Nothing could make them leave that position.

They delivered an iniquitous sentence that will forever weigh on our councils of war, sullying all their arrests from now with suspicion. The first council of war could have been foolish; the second was inevitably criminal. Its excuse, I repeat it, was that the supreme chief had spoken, declaring the thing considered to be unassailable, holy and higher than men, so that inferiors could not say the opposite. One speaks to us about the honor of the army, that we should like it, respect it. Ah! admittedly, yes, the army which would rise to the first threat, which would defend the French ground, it is all the people, and we have for it only tenderness and respect. But it is not a question of that, for which we precisely want dignity, in our need for justice. It is about the sword, the Master that one will give us tomorrow perhaps. And do not kiss devotedly the handle of the sword, by god!

I have shown in addition: the Dreyfus affair was the affair of the department of war, a High Command officer, denounced by his comrades of the High Command, condemned under the pressure of the heads of the High Command. Once again, it cannot restore his innocence without all the High Command being guilty. Also the offices, by all conceivable means, by press campaigns, by communications, by influences, protected Esterhazy only to convict Dreyfus a second time. What sweeping changes should the republican government should give to this [Jesuitery], as General Billot himself calls it! Where is the truly strong ministry of wise patriotism that will dare to reforge and to renew all? What of people I know who, faced with the possibility of war, tremble of anguish knowing in what hands lies national defense! And what a nest of base intrigues, gossips and dilapidations has this crowned asylum become, where the fate of fatherland is decided! One trembles in face of the terrible day that there has just thrown the Dreyfus affair, this human sacrifice of an unfortunate, a "dirty Jew"! Ah! all that was agitated insanity there and stupidity, imaginations insane, practices of low police force, manners of inquisition and tyranny, good pleasure of some non-commissioned officers putting their boots on the nation, returning in its throat its cry of truth and justice, under the lying pretext and sacrilege of the reason of State.

And it is a yet another crime to have [pressed on ?] the filthy press, to have let itself defend by all the rabble of Paris, so that the rabble triumphs insolently in defeat of law and simple probity. It is a crime to have accused those who wished for a noble France, at the head of free and just nations, of troubling her, when one warps oneself the impudent plot to impose the error, in front of the whole world. It is a crime to mislay the opinion, to use for a spiteful work this opinion, perverted to the point of becoming delirious. It is a crime to poison the small and the humble, to exasperate passions of reaction and intolerance, while taking shelter behind the odious antisemitism, from which, if not cured, the great liberal France of humans rights will die. It is a crime to exploit patriotism for works of hatred, and it is a crime, finally, to turn into to sabre the modern god, when all the social science is with work for the nearest work of truth and justice.

This truth, this justice, that we so passionately wanted, what a distress to see them thus souffletées, more ignored and more darkened! I suspect the collapse which must take place in the heart of Mr. Scheurer-Kestner, and I believe well that he will end up feeling remorse for not having acted revolutionarily, the day of questioning at the Senate, by releasing all the package, [for all to throw to bottom]. He was the great honest man, the man of his honest life, he believed that the truth sufficed for itself, especially when it seemed as bright as the full day. What good is to turn all upside down when the sun was soon to shine? And it is for this trustful neutrality for which he is so cruelly punished. The same for Major Picquart, who, for a feeling of high dignity, did not want to publish the letters of General Gonse. These scruples honour it more especially as, while there remained respectful discipline, its superiors covered it with mud, informed themselves its lawsuit, in the most unexpected and outrageous manner. There are two victims, two good people, two simple hearts, who waited for God while the devil acted. And one even saw, for Major Picquart, this wretched thing: a French court, after having let the rapporteur charge a witness publicly, to show it of all the faults, made the closed door, when this witness was introduced to be explained and defend himself. I say that this is another crime and that this crime will stir up universal conscience. Decidedly, the military tribunals have a singular idea of justice.

Such is thus the simple truth, Mr. President, and it is appalling, it will remain a stain for your presidency. I very much doubt that you have no capacity in this affair, that you are the prisoner of the Constitution and your entourage. You do not have of them less one to have of man, about which you will think, and which you will fulfill. It is not, moreover, which I despair less of the world of the triumph. I repeat it with a more vehement certainty: the truth marches on and nothing will stop it. Today, the affair merely starts, since today only the positions are clear: on the one hand, the culprits who do not want the light to come; the other, the carriers of justice who will give their life to see it come. I said it elsewhere, and I repeat it here: when one locks up the truth under ground, it piles up there, it takes there a force such of explosion, that, the day when it bursts, it makes everything leap out with it. We will see, if we do not prepare for later, the most resounding of disasters.

But this letter is long, Mr. President, and it is time to conclude.

I accuse Major Du Paty de Clam as the diabolic workman of the miscarriage of justice, without knowing, I have wanted to believe it, and of then defending his harmful work, for three years, by the guiltiest and most absurd of machinations.

I accuse General Mercier of being an accomplice, if by weakness of spirit, in one of greatest iniquities of the century.

I accuse General Billot of having held in his hands the unquestionable evidence of Dreyfus's innocence and of suppressing it, guilty of this crime that injures humanity and justice, with a political aim and to save the compromised Chie of High Command.

I accuse General De Boisdeffre and General Gonse as accomplices of the same crime, one undoubtedly by clerical passion, the other perhaps by this spirit of body which makes offices of the war an infallible archsaint.

I accuse General De Pellieux and commander Ravary of performing a rogue investigation, by which I mean an investigation of the most monstrous partiality, of which we have, in the report of the second, an imperishable monument of naive audacity.

I accuse the three handwriting experts, sirs Belhomme, Varinard and Couard, of submitting untrue and fraudulent reports, unless a medical examination declares them to be affected by a disease of sight and judgment.

I accuse the offices of the war of carrying out an abominable press campaign, particularly in the Flash and the Echo of Paris, to mislead the public and cover their fault.

Finally, I accuse the first council of war of violating the law by condemning a defendant with unrevealed evidence, and I accuse the second council of war of covering up this illegality, by order, by committing in his turn the legal crime of knowingly discharging the culprit.

While proclaiming these charges, I am not unaware of subjecting myself to articles 30 and 31 of the press law of July 29, 1881, which punishes the offense of slander. And it is voluntarily that I expose myself.

As for the people I accuse, I do not know them, I never saw them, I have against them neither resentment nor hatred. To me, they are only entities, spirits of social evil. And the act I am hereby accomplishing is only a revolutionary means to hasten the explosion of truth and justice.

I have only one passion, that of the light, in the name of humanity which has suffered so much and is entitled to happiness. My ignited protest is nothing more than the cry of my heart. So may one dare bring me to criminal court, and may the investigation take place in broad daylight!

I am waiting.

Please accept, Mr. President, the assurance of my deep respect.

![]()

![]() This work is a translation and has a separate copyright status to the applicable copyright protections of the original content.

This work is a translation and has a separate copyright status to the applicable copyright protections of the original content.

| Original: |

This work was published before January 1, 1929, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse |

|---|---|

| Translation: |

This work is licensed under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License. The Terms of use of the Wikimedia Foundation require that GFDL-licensed text imported after November 2008 must also be dual-licensed with another compatible license. "Content available only under GFDL is not permissible" (§7.4). This does not apply to non-text media.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse |