William Blake, a critical essay/The prophetic books

III.—THE PROPHETIC BOOKS.

Before entering upon any system of remark or comment on the Prophetic Books, we may set down in as few and distinct words as possible the reasons which make this a thing seriously worth doing; nay, even requisite to be done, if we would know rather the actual facts of the man's nature than the circumstances and accidents of his life. Now, first of all, we are to recollect that Blake himself regarded these works as his greatest, and as containing the sum of his achieved ambitions and fulfilled desires: as in effect inspired matter, of absolute imaginative truth and eternal import. We shall not again pause to rebut the familiar cry of response, to the effect that he was mad and not accountable for the uttermost madness of error. It must be enough to reply here that he was by no means mad, in any sense that would authorise us in rejecting his own judgment of his own aims and powers on a plea which would be held insufficient in another man's case. Let all readers and all critics get rid of that notion for good—clear their minds of it utterly and with all haste; let them know and remember, having once been told it, that in these strangest of all written books there is purpose as well as power, meaning as well as mystery. Doubtless, nothing quite like them was ever pitched out headlong into the world as they were. The confusion, the clamour, the jar of words that half suffice and thoughts that half exist—all these and other more absolutely offensive qualities—audacity, monotony, bombast, obscure play of licence and tortuous growth of fancy—cannot quench or even wholly conceal the living purport and the imperishable beauty which are here latent.

And secondly we are to recollect this; that these books are not each a set of designs with a text made by order to match, but are each a poem composed for its own sake and with its own aim, having illustrations arranged by way of frame or appended by way of ornament. On all grounds, therefore, and for all serious purpose, such notices as some of those given in this biography are actually worse than worthless. Better have done nothing than have done this and no more. All the criticism included as to the illustrative parts merely, is final and faultless, nothing missed and nothing wrong; this could not have been otherwise, the work having fallen under hands and eyes of practical taste and trained to actual knowledge, and the assertions being therefore issued by authority. So much otherwise has it fared with the books themselves, that (we are compelled in this case to say it) the clothes are all right and the body is all wrong. Passing from some phrase of high and accurate eulogy to the raw ragged extracts here torn away and held up with the unhealed scars of mutilation fresh and red upon them, what is any human student to think of the poet or his praisers? what, of the assertion of his vindicated sanity with such appalling counterproof thrust under one's eyes? In a word, it must be said of these notices of Blake's prophetic books[1] (except perhaps that insufficient but painstaking and well-meant chapter on the Marriage of Heaven and Hell) that what has been done should not have been done, and what should have been done has not been done.

Not that the thing was easy to do. If any one would realize to himself for ever a material notion of chaos, let him take a blind header into the midst of the whirling foam and rolling weed of this sea of words. Indeed the sound and savour of these prophecies constantly recall some such idea or some such memory. This poetry has the huge various monotonies, the fervent and fluent colours, the vast limits, the fresh sonorous strength, the certain confusion and tumultuous law, the sense of windy and weltering space, the intense refraction of shadow or light, the crowded life and inanimate intricacy, the patience and the passion of the sea. By no manner of argument or analysis will one be made able to look back or forward with pure confidence and comprehension. Only there are laws, strange as it must sound, by which the work is done and against which it never sins. The biographer once attempts to settle the matter by asserting that Blake was given to contradict himself, by mere impulse if not by brute instinct, to such an extent that consistency is in no sense to be sought for or believed in throughout these works of his: and quotes, by way of ratifying this quite false notion, a noble sentence from the Proverbs of Hell, aimed by Blake with all his force against that obstinate adherence to one external opinion which closes and hardens the spirit against all further message from the new-grown feelings or inspiration from the altering circumstances of a man. Never was there an error more grave or more complete than this. The expression shifts perpetually, the types blunder into new forms, the meaning tumbles into new types; the purpose remains, and the faith keeps its hold.

There are certain errors and eccentricities of manner and matter alike common to nearly all these books, and distinctly referable to the character and training of the man. Not educated in any regular or rational way, and by nature of an eagerly susceptible and intensely adhesive mind, in which the lyrical faculty had gained and kept a preponderance over all others visible in every scrap of his work, he had saturated his thoughts and kindled his senses with a passionate study of the forms of the Bible as translated into English, till his fancy caught a feverish contagion and his ear derived a delirious excitement from the mere sound and shape of the written words and verses. Hence the quaint and fervent imitation of style, the reproduction of peculiarities which to most men are meaningless when divested of their old sense or invested with a new. Hence the bewildering catalogues, genealogies, and divisions which (especially in such later books as the Jerusalem) seem at first invented only to strike any miserable reader with furious or lachrymose lunacy. Hence, though heaven knows by no fault of the originals, the insane cosmogony, blatant mythology, and sonorous aberration of thoughts and theories. Hence also much of the special force and supreme occasional loveliness or grandeur in expression. Conceive a man incomparably gifted as to the spiritual side of art, prone beyond all measure to the lyrical form of work, incredibly contemptuous of all things and people dissimilar to himself, of an intensely sensitive imagination and intolerant habit of faith, with a passionate power of peculiar belief, taking with all his might of mental nerve and strain of excitable spirit to a perusal and reperusal of such books as Job and Ezekiel. Observe too that his tone of mind was as far from being critical as from being orthodox. Thus his ecstacy of study was neither on the one side tempered and watered down by faith in established forms and external creeds, nor on the other side modified and directed by analytic judgment and the lust of facts. To Blake either form of mind was alike hateful. Like the Moses of Rabbinical tradition, he was "drunken with the kisses of the lips of God." Rational deism and clerical religion were to him two equally abhorrent incarnations of the same evil spirit, appearing now as negation and now as restriction. He wanted supremacy of freedom with intensity of faith. Hence he was properly neither Christian nor infidel: he was emphatically a heretic. Such men, according to the temper of the times, are burnt as demoniacs or pitied as lunatics. He believed in redemption by Christ, and in the incarnation of Satan as Jehovah. He believed that by self-sacrifice the soul should attain freedom and victorious deliverance from bodily bondage and sexual servitude; and also that the extremest fullness of indulgence in such desire and such delight as the senses can aim at or attain was absolutely good, eternally just, and universally requisite. These opinions, and stranger than these, he put forth in the cloudiest style, the wilfullest humour, and the stormiest excitement. No wonder the world let his books drift without caring to inquire what gold or jewels might be washed up as waifs from the dregs of churned foam and subsiding surf. He was the very man for fire and faggot; a mediæval inquisitor would have had no more doubt about him than a materialist or "theophilanthropist " of his own day or of ours.

A wish is expressed in the Life that we could accompany the old man who appears entering an open door, star in hand, at the beginning of the Jerusalem, and thread by his light those infinite dark passages and labyrinthine catacombs of invention or thought. In default of that desirable possibility, let us make such way as we can for ourselves into this submarine world, along its slippery and unpaven ways, under its roof of hollow sound and tumbling storm.

We shall see, while above us

The waves roar and whirl,

A ceiling of amber,

A pavement of pearl."

At the entrance of the labyrinth we are met by huge mythologic figures, created of fire and cloud. Titans of monstrous form and yet more monstrous name obstruct the ways; sickness or sleep never formed such savage abstractions, such fierce vanities of vision as these: office and speech they seem at first to have none: but to strike or clutch at the void of air with feeble fingers, to babble with vast lax lips a dialect barren of all but noise, loud and loose as the wind. Slowly they grow into something of shape, assume some foggy feature and indefinite colour: word by word the fluctuating noise condenses into music, the floating music divides into audible notes and scales. The sound which at first was as the mere collision of cloud with cloud is now the recognizable voice of god or demon. Chaos is cloven into separate elements; air divides from water, and earth releases fire. Upon each of these the prophet, as it were, lays hand, compelling the thing into shape and speech, constraining the abstract to do service as a man might. These and such as these make up the personal staff or executive body of his prophecies. But it would be waste of time to conjecture how or why he came to inflict upon them such incredible names. These hapless energies and agencies are not simply cast into the house of allegoric bondage, and set to make bricks without straw, to construct symbols without reason; but find themselves baptized with muddy water and fitful fire, by names inconceivable, into a church full of storm and vapour; regenerated with a vengeance, but disembodied and disfigured in their resurrection. Space fell into sleep, and awoke as Enitharmon: Time suffered eclipse, and came forth as Los. The Christ or Prometheus of this faith is Orc or Fuzon; Urizen takes the place of "Jehovah, Jove, or Lord." Hardly in such chaotic sounds can one discern the slightest element of reason gone mad, the narrowest channel of derivation run dry. In this last word, one of incessant recurrence, there seems to flicker a thin reminiscence of such names as Uranus, Uriel, and perhaps Urien; for the deity has a diabolic savour in him, and Blake was not incapable of mixing the Hellenic, the Miltonic, and the Celtic mythologies into one drugged and adulterated compound. He had read much and blindly; he had no leaning to verbal accuracy, and never acquired any faculty of comparison. Any sound that in the dimmest way suggested to him a notion of hell or heaven, of passion or power, was significant enough to adopt and register. Commentary was impossible to him: if his work could not be apprehended or enjoyed by an instinct of inspiration like his own, it was lost labour to dissect or expound; and here, if ever, translation would have been treason. He took the visions as they came; he let the words lie as they fell. These barbarous and blundering names are not always without a certain kind of melody and an uncertain sort of meaning. Such as they are, they must be endured; or the whole affair must be tossed aside and thrown up. Over these clamorous kingdoms of speech and dream some few ruling forces of supreme discord preside: and chiefly the lord of the world of man; Urizen, God of cloud and star, "Father of jealousy," clothed with a splendour of shadow, strong and sad and cruel; his planet faintly glimmers and slowly revolves, a horror in heaven; the night is a part of his thought, rain and wind are in the passage of his feet; sorrow is in all his works; he is the maker of mortal things, of the elements and sexes; in him are incarnate that jealousy which the Hebrews acknowledged and that envy which the Greeks recognized in the divine nature; in his worship faith remains one with fear. Star and cloud, the types of mystery and distance, of cold alienation and heavenly jealousy, belong of right to the God who grudges and forbids: even as the spirit of revolt is made manifest in fiery incarnation—pure prolific fire, "the cold loins of Urizen dividing." These two symbols of "cruel fear" or "starry jealousy" in the divine tyrant, of ardent love or creative lust in the rebellious saviour of man, pervade the mystical writings of Blake. Orc, the manchild, with hair and flesh like fire, son of Space and Time, a terror and a wonder from the hour of his birth, containing within himself the likeness of all passions and appetites of men, is cast out from before the face of heaven; and falling upon earth, a stronger Vulcan or Satan, fills with his fire the narrowed foreheads and the darkened eyes of all that dwell thereon; imprisoned often and fed from vessels of iron with barren food and bitter drink,[2] a wanderer or a captive upon earth, he shall rise again when his fire has spread through all lands to inflame and to infect with a strong contagion the spirit and the sense of man, and shall prevail against the law and the commandments of his enemy. This endless myth of oppression and redemption, of revelation and revolt, runs through many forms and spills itself by strange straits and byways among the sands and shallows of prophetic speech. But in these books there is not the substantial coherence of form and reasonable unity of principle which bring within scope of apprehension even the wildest myths grown out of unconscious idealism and impulsive tradition. A single man's work, however exclusively he may look to inspiration for motive and material, must always want the breadth and variety of meaning, the supple beauty of symbol, the infectious intensity of satisfied belief, which grow out of creeds and fables native to the spirit of a nation, yet peculiar to no man or sect, common yet sacred, not invented or constructed, but found growing and kept fresh with faith. But for all the dimness and violence of expression which pervert and darken the mythology of these attempts at gospel, they have qualities great enough to be worth finding out. Only let none conceive that each separate figure in the swarming and noisy life of this populous dæmonic creation has individual meaning and vitality. Blake was often taken off his feet by the strong currents of fancy, and indulged, like a child during its first humour of invention, in wild byplay and erratic excesses of simple sound; often lost his way in a maze of wind-music, and transcribed as it were with eyes closed and open ears the notes caught by chance as they drifted across the dream of his subdued senses. Alternating between lyrical invention and gigantic allegory, it is hard to catch and hold him down to any form or plan. At one time we have mere music, chains of ringing names, scattered jewels of sound without a thread, tortuous network of harmonies without a clue; and again we have passages, not always unworthy of an Æschylean chorus, full of fate and fear; words that are strained wellnigh in sunder by strong significance and earnest passion; words that deal greatly with great things, that strike deep and hold fast; each inclusive of some fierce apocalypse or suggestive of some obscure evangel. Now the matter in hand is touched with something of an epic style; the narrative and characters lose half their hidden sense, and the reciter passes from the prophetic tripod to the seat of a common singer; mere names, perhaps not even musical to other ears than his, allure and divert him; he plays with stately cadences, and lets the wind of swift or slow declamation steer him whither it will. Now again he falls with renewed might of will to his purpose; and his grand lyrical gift becomes an instrument not sonorous merely but vocal and articulate. To readers who can but once take their stand for a minute on the writer's footing, look for a little with his eyes and listen with his ears, even the more incoherent cadences will become not undelightful; something of his pleasure, with something of his perception, will pass into them; and understanding once the main gist of the whole fitful and high-strung tune, they will tolerate, where they cannot enjoy, the strange diversities and discords which intervene.

Among many notable eccentricities we have touched upon but two as yet; the huge windy mythology of elemental dæmons, and the capricious passion for catalogues of random names, which make obscure and hideous so, much of these books. Akin to these is the habit of seeing or assuming in things inanimate or in the several limbs and divisions of one thing, separate forms of active and symbolic life. This, like many other of Blake's habits, grows and swells enormously by progressive indulgence. At first, as in Thel, clouds and flowers, clods and creeping things, are given speech and sense; the degree of symbolism is already excessive, owing to the strength of expression and directness of dramatic vision peculiar to Blake; but in later books everything is given a soul to feel and a tongue to speak; the very members of the body become spirits, each a type of some spiritual state. Again, in the prophecies of Europe and America, there is more fable and less allegory, more overflow of lyrical invention, more of the divine babble which sometimes takes the place of earthly speech or sense, more vague emotion with less of reducible and amenable quality than in almost any of these poems. In others, a habit of mapping out and marking down the lines of his chaotic and Titanic scenery has added to Blake's other singularities of manner this above all, that side by side with the jumbled worlds of Tharmas and Urthona, the whirling skies and plunging planets of Ololon and Beulah, the breathless student of prophecy encounters places and names absurdly familiar; London streets and suburbs make up part of the mystic antediluvian world; Fulham and Lambeth, Kentish Town and Poland Street, cross the courses and break the metres of the stars. This apparent madness of final absurdity has also its root in the deepest and soundest part of Blake's mind and faith. In the meanest place as in the meanest man he beheld the hidden spirit and significance of which the flesh or the building is but a type. If continents have a soul, shall suburbs or lanes have less? where life is, shall not the spirit of life be there also? Europe and America are vital and significant; we mean by all names somewhat more than we know of; for where there is anything visible or conceivable, there is also some invisible and inconceivable thing. This is but the rough grotesque result of the tenet that matter apart from spirit is non-existent. Launched once upon that theory, Blake never thought it worth while to shorten sail or tack about for fear of any rock or shoal. It is inadequate and even inaccurate to say that he allotted to each place as to each world a presiding dæmon or deity. He averred implicitly or directly, that each had a soul or spirit, the quintessence of its natural life, capable of change but not of death; and that of this soul the visible externals, though a native and actual part, were only a part, inseparable as yet but incomplete. Thus whenever, to his misfortune and ours, he stumbles upon the proper names of terrene men and things, he uses these names as signifying not the sensual form or body but the spirit which he supposed to animate these, to speak in them and work through them. In America the names of liberators, in Jerusalem the names of provinces, have no separate local or mundane sense whatever; throughout the prophecies "Albion" is the mythical and typical fatherland of human life, much what the East might seem to other men: and by way of making this type actual and prominent enough, Blake seizes upon all possible divisions of the modern visible England in town or country, and turns them in his loose symbolic way into minor powers and serving spirits. That he was wholly unconscious of the intolerably laughable effect we need not believe. He had all the delight in laying snares and giving offence, which is proper to his kind. He had all the confidence in his own power and right to do such things and to get over the doing of them which accompanies in such men the subtle humour of scandalizing. And unfortunately he had not by training, perhaps not by nature, the conscience which would have reminded him that whether or not an artist may allowably play with all other things in heaven and earth, one thing he must certainly not play with; the material forms of art: that levity and violence are here prohibited under grave penalties. Allowing however for this, we may notice that in the wildest passages of these books Blake merely carries into strange places or throws into strange shapes such final theories as in the dialect of calmer and smaller men have been accounted not unreasonable.

Further preface or help, however loudly the subject might seem to call for it, we have not in this place to give; and indeed more words would possibly not bring with them more light. What was explicable we have endeavoured to explain; to suggest where a hint was profitable; to prepare where preparation was feasible: but many voices might be heard crying in this wilderness before the paths were made straight. The pursuivant would grow hoarse and the outrider saddle-sick long before the great man's advent; and for these offices we have no further taste or ability. Those who will may now, with what furtherance they have here, follow us through some brief revision of each book in its order.[3]

The Book of Thel, first in date and simplest in tone of the prophecies, requires less comment than the others. This poem is as the one sister, feeblest if also fairest, among that Titanic brotherhood of books. It has the clearness and sweetness of spring-water; they have in their lips the speech, in their limbs the pulses of the sea. In this book, as in the illustrations to Blair, the poet attempts to comfort life through death; to assuage by spiritual hope the fleshly fear of man. The "shining woman," youngest and mortal daughter of the angels of God, leaving her sisters to tend the flocks and close the folds of the stars, fills herself with the images of perishable things; she feeds upon the sorrow that comes of beauty, the heathen weariness of heart, that is sick of life because death will come, seeing how "our little life is rounded with a sleep." Let all these things go, for they are mortal; but if I die with the flowers, let me also die as they die. This is the end of all things, to sleep; but let me fall asleep softly, not without the lulling sound of

It is well worth while to compare any average copy of Thel with the smaller volume of designs now in the British Museum, which reproduces among others the main illustrations of this book. The clear, sweet, pallid colour of the fainter version will then serve to throw into full effect the splendour of the more finished work. Especially in the separate copy of the frontispiece, the sovereignty of colour and glorious grace of workmanship double and treble its original beauty; give new light and new charm to the fervent heaven, to the bowing figure of the girl, to the broad cloven blossoms whose flickering and sundering petals release the bright leaping forms of loving spirits, raindrop and dewdrop wedded before the sun; and again, where Thel sees the worm in likeness of a newborn child, the colours of tree and leaf and sky are of a more excellent and lordly beauty than in any copy known to me of the book itself; though in all good copies these designs appear full of great and gracious qualities. Of the book of designs here referred to more must not now be said; not even of the twelfth plate where the mother-goddess and her fiery first-born child exult with flying wingless limbs through splendid spaces of the infinite morning, coloured here like opening flowers and there like climbing fire, where all the light and all the wind of heaven seem to unite in fierce gladness as of a supreme embrace and exultation; for to these better praise than ours has been already given at p. 374 of the Life, in words of choice and incomparable sufficiency, not less bright and sweet, significant and subtle, than the most tender or perfect of the designs described.

In 1790 Blake produced the greatest of all his books; a work indeed which we rank as about the greatest produced by the eighteenth century in the line of high poetry and spiritual speculation. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell gives us the high-water mark of his intellect. None of his lyrical writings show the same sustained strength and radiance of mind; none of his other works in verse or prose give more than a hint here and a trace there of the same harmonious and humorous power, of the same choice of eloquent words, the same noble command and liberal music of thought; small

It was part of Blake's humour to challenge misconception, conscious as he was of power to grapple with it: to blow dust in their eyes who were already sandblind, to strew thorns under their feet who were already lame. Those whom the book in its present shape would perplex and repel he knew it would not in any form have attracted; and how such readers may fare is no concern of such writers; nor in effect need it be. Aware that he must at best offend a little, he did not fear to offend much. To measure the exact space of safety, to lay down the precise limits of offence, was an office neither to his taste nor within his power. Those who try to clip or melt themselves down to the standard of current feeling, to sauce and spice their natural fruits of mind with such condiments as may take the palate of common opinion, deserve to disgust themselves and others alike. It is hopeless to reckon how far the timid, the perverse, or the malignant irrelevance of human remarks will go; to set bounds to the incompetence or devise landmarks for the imbecility of men. Blake's way was not the worst; to indulge his impulse to the full and write what fell to his hand, making sure at least of his own genius and natural instinct. In this his greatest book he has at once given himself freer play and set himself to harder labour than elsewhere: the two secrets of great work. Passion and humour are mixed in his writing like mist and light; whom the light may scorch or the mist confuse it is not his part to consider.

In the prologue Blake puts forth, not without grandeur if also with an admixture of rant and wind, a chief tenet of his moral creed. Once the ways of good and evil were clear, not yet confused by laws and religions; then humility and benevolence, the endurance of peril and the fruitful labour of love, were the just man's proper apanage; behind his feet the desert blossomed; by his toil and danger, by his sweat and blood, the desolate places were made rich and the dead bones clothed with flesh as the flesh of Adam. Now the hypocrite has come to reap the fruits, to divide and gather and eat; to drive forth the just man and to dwell in the paths which he found perilous and barren, but left safe and fertile. Churches have cast out apostles; creeds have rooted out faith. Henceforth anger and loneliness, the divine indignation of spiritual exile, the salt bread of scorn and the bitter wine of wrath, are the portion of the just man; he walks with lions in the waste places, not worth making fertile that others may reap and feed. "Rintrah," the spirit presiding over this period, is a spirit of fire and storm; darkness and famine, wrath and want, divide the kingdoms of the world. "Prisons are built with stones of Law; brothels with bricks of Religion." "As the caterpillar chooses the fairest leaves to lay her eggs on, so the priest lays his curse on the fairest joys." In a third proverb the view given of prayer is no less heretical; "As the plough follows words, so God rewards prayers." This was but the outcome or corollary of his main doctrine; as what we have called his "evangel of bodily liberty" was but the fruit of his belief in the identity of body with soul. The fear which restrains and the faith which refuses were things as ignoble as the hypocrisy which assumes or the humility which resigns. Veils and chains must be lifted and broken. "Folly is the cloak of knavery; shame is pride's cloak." Again; "He who desires but acts not breeds pestilence." "Sooner murder an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires." The doctrine of freedom could hardly run further or faster. Translated into rough practice, and planted in a less pure soil than that of the writer's mind, this philosophy might bring forth a strange harvest. Together with such width of moral pantheism as will hardly admit a "tender curb," leave "a little curtain of flesh on the bed of our desire," there is a vehemence of faith in divine wrath, in the excellence of righteous anger and revenge, to be outdone by no prophet or Puritan. "A dead body revenges not injuries." Sincerity and plain dealing at least are virtues not to be thrown over; Blake indeed could not conceive an impulse to mendacity, a tortuous habit of mind, a soul born crooked. This one quality of falsehood remains damnable in his sight, to be consumed with all that comes of it. In man or beast or any other part of God he found no native taint or birthmark of this. Upon all else the divine breath and the divine hand are sensible and visible.

The pride of the peacock is the glory of God;

The lust of the goat is the bounty of God;

The wrath of the lion is the wisdom of God;

The nakedness of woman is the work of God."

All form and all instinct is sacred; but no invention or device of man's. All crafts and creeds of theirs are "the serpent's meat:" and that a man should be born cruel and false is barely imaginable. "If the lion was advised by the fox he would be cunning." Such counsel was always wasted on the high clear spirit and stainless intellect of Blake.

We have given some of the most subtle and venturous "Proverbs of Hell"—samples of their depth of doctrine and plainness of speech. But even here Blake rarely indulges in such excess and exposure. There are jewels in this treasure-house neither set so roughly nor so sharply

these things come from hell, let us look to it and hold them fast, that we may see what it is that divides hell from heaven.

"As a new heaven is begun, and it is now thirty-three years since its advent: the Eternal Hell revives. And lo! Swedenborg is the Angel sitting at the tomb : his writings are the linen clothes folded up. Now is the dominion of Edom, and the return of Adam into Paradise; see Isaiah xxxiv. and xxxv. chap.

"Without Contraries is no progression. Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate, are necessary to Human exisence.

"From these Contraries spring what the religious call Good and Evil. Good is the passive that obeys Reason.

"Evil is the active springing from Energy.

"Good is Heaven. Evil is Hell.

"THE VOICE OF THE DEVIL.

"All Bibles or sacred codes have been the causes of the following Errors.

"1. That man has two real existing principles - viz., a Body and a Soul.

"2. That Energy, called Evil, is alone from the Body; and that Reason, called Good, is alone from the Soul.

"3. That God will torment Man in Eternity for following his Energies.

"But the following contraries to these are True.

"1. Man has no Body distinct from his Soul, for that called Body is a portion of Soul discerned by the five Senses, the chief inlets of Soul in this age.

"2. Energy is the only life, and is from the Body; and Reason is the bound or outward circumference of Energy.

"3. Energy is Eternal Delight.

"Those who restrain desire to do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained; and the restrainer, or reason, usurps its place and governs the unwilling.

"And being restrained it by degrees becomes passive, till it is only the shadow of desire.

"The history of this is written in ' Paradise Lost,' and the Governor, or Reason, is called Messiah.

"And the original Archangel, or possessor of the command of the heavenly host, is called the Devil or Satan, and his children are called Sin and Death.

"But in the Book of Job Milton's Messiah is called Satan.

"For this history has been adopted by both parties.

"It indeed appeared to Reason as if Desire was cast out; but the Devil's account is, that the Messiah fell, and formed a heaven of what he stole from the Abyss.

"This is shewn in the Gospel, where he prays to the Father to send the comforter or Desire, that Reason may have Ideas to build on, the Jehovah of the Bible being no other than he who dwells in flaming fire. Know that after Christ's death, he became Jehovah.

"But in Milton the Father is Destiny, the Son a Ratio of the five Senses, and the Holy Ghost, Vacuum.

"Note.—The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true Poet, and of the Devil's party without knowing it."

Something of these high matters we have seen before, and should now be able to allow for the subtle intricate fashion in which Blake labours to invert the weapons of his antagonists upon themselves. Neither can the banns of marriage be published between heaven and hell with the voice of a parish clerk. This prophet came to do what Swedenborg his precursor had left undone, being but the watchman by the empty sepulchre, and his writings as the grave-clothes cast off by the risen Christ. Blake's estimate of Swedenborg, right or wrong, was, as we shall see, distinct and consistent; to this effect; that his inspiration was limited and timid, superficial and derivative; that he was content with leaves and husks, and had not the courage to examine the root and the kernel of things; that he clove to the heaven and shrank from the hell of other men; whereas, to men in whom "a new heaven is begun," the one must not be terrible nor the other desirable. To them the "flaming fire" wherein dwells a God whom men call devil, must seem a purer element of life than the starry and cloudy space wherein dwells a devil whom they call God. It must be remembered that Blake uses the current terms of religion, now as types of his own peculiar faith, now in the sense of ordinary preachers: impugning therefore at one time what at another he will seem to vindicate. Vague and violent as this overture may appear, it must be followed with care, that the writer's intensity of spiritual faith may be hereafter kept in sight. The senses, "the chief inlets of soul in this age" of brute doubt and brute belief, are worthy only as parts of the soul. This, it cannot be too much repeated and insisted on, this and no prurience of porcine appetite for rotten apples, no vulgarity of porcine adoration for unctuous wash, is what lies at the root of Blake's sensual doctrine. Let no reader now or ever forget, that while others will admit nothing beyond the body, the mystic will admit nothing outside the soul. That the two extremes, if reduced to hard practice, might run round and meet, not without lamentably curious consequences, those may assert who will; it is none of our business to decide. Even granting that the result will be about equivalent if one man does for his soul's sake all that another would do for his body's sake, we might plead that the difference of thought and eye between these two would remain great and important. Indulgence bracketed to faith and vivified by that vigorous contact with things divine is not (we might say) the same, whether seen from the actual side of life or from the speculative, as indulgence cut loose and left to decompose. But these pleas we will leave the mystic to advance, if it please him, on his own behalf.

"A Memorable Fancy.

"As I was walking among the fires of hell, delighted with the enjoyments of Genius, which to Angels look like torment and insanity, I collected some of their Proverbs: thinking that as the sayings used in a nation mark its character, so the Proverbs of Hell show the nature of the Infernal wisdom better than any description of buildings or garments. When I came home, on the abyss of the five senses, where a flat-sided steep frowns over the present world, I saw a mighty Devil folded in black clouds, hovering on the sides of the rock; with corroding fires he wrote the following sentence, now perceived by the minds of men, and read by them on earth:—

"'How do you know but ev'ry Bird that cuts the airy way

Is an immense world of delight, clos'd by your senses five?'"

Here follow the "Proverbs of Hell," which give us the quintessence and the most fine gold of Blake's alembic. Each, whether earnest or satirical, slight or great in manner, is full of that passionate wisdom and bright rapid strength proper to the step and speech of gods. The simplest give us a measure of his energy, as this: "Think in the morning, act in the noon, eat in the evening, sleep in the night." The highest have a light and resonance about them, as though in effect from above or beneath; a spirit which lifts thought upon the high levels of verse.

From the ensuing divisions of the book we shall give full extracts; for these detached sections have a grace and coherence which we shall not always find in Blake; and the crude excerpts given in the Life are inadequate to help the reader much towards a clear comprehension of the main scheme.

"The ancient Poets animated all sensible objects with Gods or Geniuses, calling them by the names and adorning them with the properties of woods, rivers, mountains, lakes, cities, nations, and whatever their enlarged and numerous senses could perceive.

"And, particularly, they studied the genius of each city and country, placing it under its mental deity.

"Till a system was formed, which some took advantage of and enslaved the vulgar by attempting to realize or abstract the mental deities from their objects: thus began Priesthood,

"Choosing forms of worship from poetic tales;

"And at length they pronounced that the Gods had ordered such things.

"Thus men forgot that All deities reside in the human breast."

From this we pass to higher tones of exposition. The next passage is one of the clearest and keenest in the book, full of faith and sacred humour, none the less sincere for its dramatic form. The subtle simplicity of expression is excellently subservient to the intricate force of thought.

"A Memorable Fancy.

"The Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel dined with me, and I asked them how they dared so roundly to assert that God spoke to them; and whether they did not think at the time that they would be misunderstood, and so be the cause of imposition.

"Isaiah answered, "I saw no God, nor heard any, in a finite or organical perception; but my senses discovered the infinite in everything, and as I was then persuaded, I remain confirmed, that the voice of honest indignation is the voice of God. I cared not for consequences, but wrote.'

"Then I asked, 'Does a firm persuasion that a thing is so, make it so?'

"He replied, 'All poets believe that it does, and in ages of imagination this firm persuasion removed mountains. But many are not capable of a firm persuasion of anything.'

"Then Ezekiel said, "The philosophy of the East taught the first principles of human perception. Some nations held one principle for the origin and some another. We of Israel taught that the Poetic Genius (as you now call it) was the first principle, and all the others merely derivative, which was the cause of our despising the Priests and Philosophers of other countries, and prophesying that all Gods would at last be proved to originate in ours, and to be the tributaries of the Poetic Genius. It was this that our great poet King David desired so fervently and invokes so pathetically, saying by this he conquers enemies and governs kingdoms; and we so loved our God, that we cursed in his name all the deities of surrounding nations, and asserted that they had rebelled; from these opinions the vulgar came to think that all nations would at last be subject to the Jews.

"'This,' said he, 'like all firm persuasions, is come to pass, for all nations believe the Jews' code and worship the Jews' God, and what greater subjection can be?'

"I heard this with some wonder, and must confess my own conviction. After dinner, I asked Isaiah to favour the world with his lost works. He said none of equal value was lost. "Ezekiel said the same of his.

"I also asked Isaiah what made him go naked and barefoot three years? He answered, the same that made our friend Diogenes the Grecian.

"I then asked Ezekiel, why he eat dung, and lay so long on his right and left side? he answered, the desire of raising other men into a perception of the infinite. This the North American tribes practise; and is he honest who resists his genius or conscience, only for the sake of present ease or gratification?"

The doctrine of perception through not with the senses, beyond not in the organs, as also of the absolute existence of things thus apprehended, is again directly enforced in our next excerpt; in praise of which we will say nothing, but leave the words to burn their way in as they may.

"The ancient tradition that the world will be consumed in fire at the end of six thousand years is true, as I have heard from Hell.

"For the cherub with his flaming sword is hereby commanded to leave his guard at the tree of life; and when he does, the whole creation will be consumed, and appear infinite and holy, whereas it now appears finite and corrupt.

"This will come to pass by an improvement of sensual enjoyment.

"But first the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul is to be expunged; this I shall do, by printing in the infernal method, by corrosives, which in Hell are salutary and medicinal, melting apparent surfaces away and displaying the infinite which was hid.

"If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.

"For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things through narrow chinks of his cavern."

"The Giants who formed this world into its sensual existence, and now seem to live in it in chains, are in truth the causes of its life and the sources of all activity; but the chains are, the cunning of weak and tame minds, which have power to resist energy; according to the proverb, the weak in courage is strong in cunning.

"Thus one portion of being is the Prolific, the other, the Devouring; to the devourer it seems as if the producer was in his chains; but it is not so; he only takes portions of existence and fancies that the whole.

"But the Prolific would cease to be Prolific, unless the Devourer as a sea received the excess of his delights.

"Some will say, Is not God alone the Prolific?

"I answer, God only Acts and Is in existing beings or Men.

"These two classes of men are always upon earth, and they should be enemies; whoever tries to reconcile them, seeks to destroy existence.

"Religion is an endeavour to reconcile the two.

"Note.—Jesus Christ did not wish to unite but to separate them, as in the Parable of sheep and goats! and he says I came not to send Peace but a Sword.

"Messiah or Satan or Tempter was formerly thought to be one of the Antediluvians who are our Energies."

These are hard sayings; who can hear them? At first sight also, as we were forewarned, this passage seems at direct variance with that other in the overture, where our prophet appears at first sight, and only appears, to speak of the fallen "Messiah" as the same with the Christ of his belief. Verbally coherent we cannot hope to make the two passages; but it must be remarked and remembered that the very root or kernel of this creed is not the assumed humanity of God, but the achieved divinity of Man; not incarnation from without, but development from within; not a miraculous passage into flesh, but a natural growth into godhead. Christ, as the type or sample of manhood, thus becomes after death the true Jehovah; not, as he seems to the vulgar, the extraneous and empirical God of creeds and churches, human in no necessary or absolute sense, the false and fallen phantom of his enemy, Zeus in the mask of Prometheus. We are careful to note and as far as may be to correct any apparent slips or shortcomings in expression, only because if left without a touch of commentary they may seem to make worse confusion than they do actually make. Subtle, trenchant and profound as is this philosophy, there is no radical flaw in the book, no positive incongruity, no inherent contradiction. A single consistent principle keeps alive the large relaxed limbs, makes significant the dim great features of this strange faith. It is but at the opening that the words are even partially inadequate and obscure. Revision alone could have righted and straightened them; and revision the author would not give. Impatient of their insufficiency, and incapable of any labour that implies rest, he shook them together and flung them out in an irritated hurried manner, regardless who might gather them up or let them lie.

In the next and longest division of the book, direct allegory and imaginative vision are indivisibly mixed into each other. The stable and mill, the twisted root and inverted fungus, are transparent symbols enough: the splendid and stormy apocalypse of the abyss is a chapter of pure vision or poetic invention. Why "Swedenborg's volumes" are the weights used to sink the travellers from the "glorious clime" to the passive and iron void between the fixed stars and the coldest of the remote planets, will be conceivable in due time.

"A Memorable Fancy.

"An Angel came to me and said, 'O pitiable foolish young man! O horrible! O dreadful state! Consider the hot burning dungeon thou art preparing for thyself to all eternity, to which thou art going in such career.'

"I said, 'Perhaps you will be willing to show me my eternal lot and we will contemplate upon it and see whether your lot or mine is most desirable.'

"So he took me through a stable and through a church and down into the church vault at the end of which was a mill; through the mill we went, and came to a cave; down the winding cavern we groped our tedious way, till a void, boundless as a nether sky, appeared beneath us, and we held by the roots of trees and hung over this immensity; but I said, 'If you please, we will commit ourselves to this void, and see whether Providence is here also; if you will not, I will.'

"But he answered, 'Do not presume, O young man, but as we here remain, behold thy lot, which will soon appear when the darkness passes away.'

"So I remained with him, sitting in the twisted root of an oak; he was suspended in a fungus, which hung with the head downward into the deep.

"By degrees we beheld the infinite Abyss, fiery as the smoke of a burning city; beneath us at an immense distance was the sun, black but shining; round it were fiery tracks on which revolved vast spiders, crawling after their prey; which flew or rather swam in the infinite deep, in the most terrific shapes of animals sprung from corruption; and the air was full of them, and seemed composed of them; these are Devils, and are called Powers of the air. I now asked my companion which was my eternal lot? he said, between the black and white spiders.

"But now, from between the black and white spiders a cloud and fire burst and rolled through the deep blackening all beneath, so that the nether deep grew black as a sea and rolled with a terrible noise: beneath us was nothing now to be seen but a black tempest, till looking east between the clouds and the waves, we saw a cataract of blood mixed with fire, and not many stones' throw from us appeared and sunk again the scaly fold of a monstrous serpent; at last, to the east, distant about three degrees, appeared a fiery crest above the waves; slowly it reared, like a ridge of golden rocks, till we discovered two globes of crimson fire, from which the sea fled away in clouds of smoke: and now we saw it was the head of Leviathan; his forehead was divided into streaks of green and purple, like those on a tiger's forehead: soon we saw his mouth and red gills hang just above the raging foam, tinging the black deep with beams of blood, advancing toward us with all the fury of a spiritual existence.

"My friend the Angel climbed up from his station into the mill; I remained alone, and then this appearance was no more; but I found myself sitting on a pleasant bank beside a river by moonlight, hearing a harper who sung to the harp, and his theme was, The man who never alters his opinion is like standing water, and breeds reptiles of the mind.

"But I arose, and sought for the mill, and there I found my Angel, who, surprised, asked me how I escaped?

"I answered, 'All that we saw was owing to your metaphysics: for when you ran away, I found myself on a bank by moonlight hearing a harper. But now we have seen my eternal lot, shall I show you yours?' He laughed at my proposal: but I by force suddenly caught him in my arms, and flew westerly through the night, till we were elevated above the earth's shadow: then I flung myself with him directly into the body of the sun; here I clothed myself in white, and taking in my hand Swedenborg's volumes, sunk from the glorious clime, and passed all the planets till we came to Saturn: here I staid to rest, and then leaped into the void, between Saturn and the fixed stars.

"'Here,' said I, 'is your lot, in this space, if space it may be called.' Soon we saw the stable and the church, and I took him to the altar and opened the Bible, and lo! it was a deep pit, into which I descended, driving the Angel before me; soon we saw seven houses of brick; one we entered; in it were a number of monkeys, baboons, and all of that species chained by the middle, grinning and snatching at one another, but withheld by the shortness of their chains; however, I saw that they sometimes grew numerous, and then the weak were caught by the strong and, with a grinning aspect, first coupled with and then devoured, by plucking off first one limb and then another, till the body was left a helpless trunk; this, after grinning and kissing it with seeming kindness, they devoured too; and here and there I saw one savourily picking the flesh off of his own tail. As the stench terribly annoyed us both, we went into the mill, and I in my hand brought the skeleton of a body, which in the mill was Aristotle's 'Analytics.'

"So the Angel said; 'Thy phantasy has imposed upon me, and thou oughtest to be ashamed.'

"I answered; 'We impose on one another, and it is but lost time to converse with you, whose works are only Analytics.'"

The "seven houses of brick" we may take to be a reminiscence of the seven churches of St. John; as indeed the traces of former evangelists and prophets are never long wanting when we track the steps of this one. Lest however we be found unawares on the side of these hapless angels and baboons, we will abstain with all due care from any not indispensable analysis. It is evident that between pure "phantasy" and mere "analytics" the great gulf must remain fixed, and either party appear to the other deceptive and deceived. That impulsive energy and energetic faith are the only means, whether used as tools of peace or as weapons of war, to pave or to fight our way toward the realities of things, was plainly the creed of Blake; as also that these realities, once well in sight, will reverse appearance and overthrow tradition: hell will appear as heaven, and heaven as hell. The abyss once entered with due trust and courage appears a place of green pastures and gracious springs: the paradise of resignation once beheld with undisturbed eyes appears a place of emptiness or bondage, delusion or cruelty. On the humorous beauty and vigour of these symbols we need not expatiate; in these qualities Rabelais and Dante together could hardly have excelled Blake at his best. What his meaning is should by this time be as clear as the meaning of a mystic need be; it is but partially expressible by words, as (to borrow Blake's own symbol) the inseparable soul is yet but incompletely expressible through the body. Whether it be right or wrong, foolish or wise, we will neither inquire nor assert: the autocercophagous monkeys of the mill may be left to settle that for themselves with "Urizen."

We come now to a chapter of comments, intercalated between two sufficiently memorable "fancies."

"I have always found that Angels have the vanity to speak of themselves as the only wise; this they do with a confident insolence sprouting from systematic reasoning.

"Thus Swedenborg boasts that what he writes is new, though it is only the Contents or Index of already published books.

"A man carried a monkey about for a show, and because he was a little wiser than the monkey, grew vain, and conceived himself as much wiser than seven men. It is so with Swedenborg: he shows the folly of churches and exposes hypocrites, till he imagines that all are religious and himself the single one on earth that ever broke a net.

"Now hear a plain fact: Swedenborg has not written one new truth.

"Now hear another: He has written all the old falsehoods.

"And now hear the reason: He conversed with Angels who are all religious and conversed not with Devils who all hate religion; for he was incapable, through his conceited notions.

"Thus Swedenborg's writings are a recapitulation of all superficial opinions, and an analysis of the more sublime, but no further.

"Hear now another plain fact: Any man of mechanical talents may, from the writings of Paracelsus or Jacob Behmen, produce ten thousand volumes of equal value with Swedenborg's; and from those of Dante or Shakespeare, an infinite number. But when he has done this, let him not say that he knows better than his master, for he only holds a candle in sunshine."

This also we will leave for those to decide who please, and attend to the next and final vision. That the fire of inspiration should absorb and convert to its own nature all denser and meaner elements of mind, was the prophet's sole idea of redemption: the dead cloud of belief consumed becomes the vital flame of faith.

"A Memorable Fancy.

"Once I saw a Devil in a flame of fire, who arose before an Angel that sat on a cloud, and the Devil uttered these words.

"The worship of God is: Honouring his gifts in other men, each according to his genius, and loving the greatest men best; those who envy or calumniate great men hate God, for there is no other God.

"The Angel hearing this became almost blue, but mastering himself, he grew yellow, and at last white, pink, and smiling; and then replied, Thou Idolater, is not God one? and is not he visible in Jesus Christ? and has not Jesus Christ given his sanction to the law of ten commandments? and are not all other men fools, sinners, and nothings?

"The Devil answered; Bray a fool in a mortar with wheat, yet shall not his folly be beaten out of him: if Jesus Christ is the greatest man, you ought to love him in the greatest degree; now hear how he has given his sanction to the law of the ten commandments: did he not mock at the sabbath, and so mock the sabbath's God? murder those who were murdered, because of him? turn away the law from the woman taken in adultery? steal the labour of others to support him? bear false witness when he omitted making a defence before Pilate? covet when he prayed for his disciples, and when he bid them shake off the dust of their feet against such as refused to lodge them? I tell you, no virtue can exist without breaking these ten commandments. Jesus was all virtue, and acted from impulse, not from rules.

"When he had so spoken, I beheld the Angel who stretched out his arms embracing the flame of fire, and he was consumed, and arose as Elijah.

"Note.—This Angel, who is now become a Devil, is my particular friend: we often read the Bible together in its infernal or diabolical sense, which the world shall have if they behave well.

"I have also the Bible of Hell, which the world shall have, whether they will or no."

Under this title at least the world was never favoured with it; but we may presumably taste some savour of that Bible in these pages. After this the book is wound up in a lyric rapture, not without some flutter and tumour of style, but full of clear high music and flame-like aspiration. Epilogue and prologue are both nearer in manner to the dubious hybrid language of the succeeding books of prophecy than to the choice and noble prose in which the rest of this book is written. The overture must be read by the light of its meaning; of the mysterious universal mother and her son, the latest birth of the world, we have already taken account. The date of 1790 must here be kept in mind, that all may remember what appearances of change were abroad, what manner of light and tempest was visible upon earth, when the hopes of such men as Blake made their stormy way into speech or song.

1. The Eternal Female groan'd! it was heard over all the Earth.

2. Albion's coast is sick silent; the American meadows faint!

3. Shadows of Prophecy shiver along by the lakes and the rivers, and mutter across the ocean. France, rend down thy dungeon;

4. Golden Spain, burst the barriers of old Rome;

5. Cast thy keys, Rome, into the deep down falling, even to eternity down falling;

6. And weep.

7. In her trembling hands she took the new-born terror howling:

8. On those infinite mountains of light now barred out by the Atlantic sea, the new-born fire stood before the starry King!

9. Flag'd with grey-browed snows and thunderous visages the jealous wings waved over the deep.

10. The speary hand burned aloft, unbuckled was the shield, forth went the hand of jealousy among the flaming hair, and hurled the new-born wonder thro' the starry night.

11. The fire, the fire is falling!

12. Look up! look up! O citizen of London, enlarge thy countenance: O Jew, leave counting gold! return to thy oil and wine; O African! black African! (go, winged thought, widen his forehead.)

13. The fiery limbs, the flaming hair, shot like the sinking sun into the western sea.

14. Waked from his eternal sleep, the hoary element roaring fled away.

15. Down rushed, beating his wings in vain, the jealous King; his grey-browed councillors, thunderous warriors, curled veterans, among helms and shields, and chariots, horses, elephants; banners, castles, slings and rocks;

16. Falling, rushing, ruining! buried in the ruins, on Urthona's dens;

17. All night beneath the ruins, then their sullen flames faded emerge round the gloomy King.

18. With thunder and fire, leading his starry hosts thro' the waste wilderness, he promulgates his ten commands, glancing his beamy eyelids over the deep in dark dismay;

19. Where the son of fire in his eastern cloud, while the morning plumes her golden breast,

20. Spurning the clouds written with curses, stamps the stony law to dust, loosing the eternal horses from the dens of night, crying, Empire is no more! and now the lion and the wolf shall cease.

CHORUS.

Let the Priests of the Raven of dawn no longer in deadly black with hoarse note curse the sons of joy; Nor his accepted brethren, whom, tyrant, he calls free, lay the bound or build the roof; Nor pale religious letchery call that virginity that wishes but acts not;

For everything that lives is Holy."

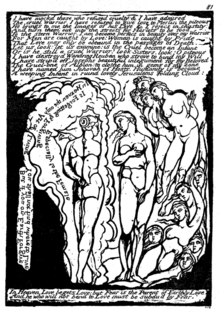

The decorations of this great work, though less large and complete than those of the subsequent prophecies, are full of noble and subtle beauty. Over every page faint fibres and flickering threads of colour weave a net of intricate design. Skies cloven with flame and thunder, half-blasted trees round which huddled forms of women or men cower and cling, strange beasts and splendid flowers, alternate with the engraved text; and throughout all the sunbeams of heaven and fires of hell shed fiercer or softer light. In minute splendour and general effect the pages of Blake's next work fall short of these; though in the Visions of the Daughters of Albion the separate designs are fuller and more composed. This poem, written in a sort of regular though quasi-lyrical blank verse, is more direct and lucid in purpose than most of these books; but the style is already laxer, veers more swiftly from point to point, stands weaker on its feet, and speaks with more of a hurried and hysterical tone. With "formidable moral questions," as the biographer has observed, it does assuredly deal; and in a way somewhat formidable. This, we are told, "the exemplary man had good right to do" Exemplary or not, he in common with all men had undoubtedly such a right; and was not slow to use it. Nowhere else has the prophet so fully and vehemently set forth his doctrine of indulgence; too Albigensian or antinomian this time to be given out again in more decorous form. Of pure mythology there is happily little; of pure allegory even less. "The eye sees more than the heart knows;" these words are given on the title-page by way of motto or key-note. Above this inscription a single design fills the page; in it the title is written with characters of pale fire upon cloud and rainbow; the figure of the typical woman, held fast to earth but by one foot, seems to soar and yearn upwards with straining limbs that flutter like shaken flame: appealing in vain to the mournful and merciless Creator, whose sad fierce face looks out beyond and over her, swathed and cradled in bloodlike fire and drifted rain. In the prologue we get a design expressive of plain and pure pleasure; a woman gathers a child from the heart of a blossom as it breaks, and the sky is full of the golden stains and widening roses of a sundawn. But elsewhere, from the frontispiece to the end, nothing meets us but emblems of restraint and error; figures rent by the beaks of eagles though lying but on mere cloud, chained to no solid rock by the fetters only of their own faiths or fancies; leafless trunks that rot where they fell; cold ripples of barren sea that break among caves of bondage. The perfect woman, Oothoon, is one with the spirit of the great western world; born for rebellion and freedom, but half a slave yet, and half a harlot. "Bromion," the violent Titan, subject himself to ignorance and sorrow, has defiled her;[5] "Theotormon," her lover, emblem of man held in bondage to creed or law, will not become one with her because of her shame; and she, who gathered in time of innocence the natural flower of delight, calls now for his eagles to rend her polluted flesh with cruel talons of remorse and ravenous beaks of shame: enjoys his infliction, accepts her agony, and reflects his severe smile in the mirrors of her purged spirit.[6]

But he

"sits wearing the threshold hard

With secret tears; beneath him sound like waves on a desert shore

The voice of slaves beneath the sun, and children bought with money."

From her long melodious lamentation we give one continuous excerpt here. Sweet, and lucid as Thel, it is more subtle and more strong; the allusions to American servitude and English aspiration, which elsewhere distract and distort the sense and scheme of the poem, are here well cleared away.

I cry Arise, O Theotormon; for the village dog

Barks at the breaking day; the nightingale has done lamenting;

The lark does rustle in the green corn, and the eagle returns

From nightly prey and lifts his golden beak to the pure east;

Shaking the dust from his immortal pinions, to awake

The sun that sleeps too long. Arise my Theotormon, I am pure

Because the night is gone that closed me in its deadly black.

They told me that the night and day were all that I could see;

They told me that I had five senses to enclose me up,

And they enclosed my infinite beam into a narrow circle,

And sank my heart into the abyss, a red round globe hotburning

Till all from life I was obliterated and erased:

Instead of morn arises a bright shadow like an eye

In the eastern cloud; instead of night a sickly charnel-house.

But Theotonnon hears me not: to him the night and morn

Are both alike; a night of sighs, a morning of fresh tears.

And none but Bromion can hear my lamentations.

With what sense is it that the chicken shuns the ravenous hawk?

With what sense does the tame pigeon measure out the expanse?

With what sense does the bee form cells? have not the mouse and frog

Eyes and ears and sense of touch? yet are their habitations

And their pursuits as different as their forms and as their joy.

Ask the wild ass why he refuses burdens, and the meek camel

Why he loves man: is it because of eye, ear, mouth or skin,

Or breathing nostrils? no: for these the wolf and tiger have.

Ask the blind worm the secrets of the grave and why her spires

Love to curl around the bones of death: and ask the ravenous snake

Where she gets poison; and the winged eagle why he loves the sun;

And then tell me the thoughts of man, that have been hid of old.

Silent I hover all the night, and all day could be silent,

If Theotormon once would turn his loved eyes upon me;

How can I be denied when I reflect thy image pure?

Sweetest the fruit that the worm feeds on, and the soul prey'd on by woe;

The new-washed lamb tinged with the village smoke, and the bright swan

By the red earth of our immortal river; I bathe my wings

And I am white and pure to hover round Theotormon's breast.

Then Theotormon broke his silence, and he answered;

Tell me what is the night or day to one overflowed with woe?

Tell me what is a thought? and of what substance is it made?

Tell me what is joy? and in what gardens do joys grow?

And in what rivers swim the sorrows? and upon what mountains

Wave shadows of discontent? and in what houses dwell the wretched

Drunken with woe forgotten, and shut up from cold despair?

Tell me where dwell the thoughts forgotten till thou call them forth?

Tell me where dwell the joys of old? and where the ancient loves?

And when will they renew again and the night of oblivion be past?

That I might traverse times and spaces far remote and bring

Comfort into a present sorrow and a night of pain!

Where goest thou, O thought? to what remote land is thy flight?

If thou returnest to the present moment of affliction

Wilt thou bring comforts on thy wings and dews and honey and balm

Or poison from the desert wilds, from the eyes of the envier?"

After this Bromion, with less musical lamentation, asks whether for all things there be not one law established? "Thou knowest that the ancient trees seen by thine eyes have fruit; but knowest thou that trees and fruits flourish upon the earth to gratify senses unknown, in worlds over another kind of seas?" Are there other wars, other sorrows, and other joys than those of external life? But the one law surely does exist "for the lion and the ox," for weak and strong, wise and foolish, gentle and fierce; and for all who rebel against it there are prepared from everlasting the fires and the chains of hell. So speaks the violent slave of heaven; and after a day and a night Oothoon lifts up her voice in sad rebellious answer and appeal.

O Urizen, Creator of men! mistaken Demon of heaven!

Thy joys are tears: thy labour vain, to form man to thine image;

How can one joy absorb another? are not different joys

Holy, eternal, infinite? and each joy is a Love.

Does not the great mouth laugh at a gift? and the narrow eyelids mock

At the labour that is above payment? and wilt thou take the ape

For thy counsellor, or the dog for a schoolmaster to thy children?

* * * * * *

Does the whale worship at thy footsteps as the hungry dog?

Or does he scent the mountain prey, because his nostrils wide

Draw in the ocean? does his eye discern the flying cloud

As the raven's eye? or does he measure the expanse like the vulture?

Does the still spider view the cliffs where eagles hide their young?

Or does the fly rejoice because the harvest is brought in?

Does not the eagle scorn the earth and despise the treasures beneath?

But the mole knoweth what is there, and the worm shall tell it thee."

Perhaps there is no loftier note of music and of thought struck anywhere throughout these prophecies. For the rest, we must tread carefully over the treacherous hot ashes strewn about the latter end of this book: which indeed speaks plainly enough for once, and with high equal eloquence; but to no generally acceptable effect. The one matter of marriage laws is still beaten upon, still hammered at with all the might of an insurgent prophet: to whom it is intolerable that for the sake of mere words and mere confusions of thought "she who burns with youth and knows no fixed lot" should be "bound by spells of law to one she loathes," should "drag the chain of life in weary lust," and "bear the wintry rage of a harsh terror driven to madness, bound to hold a rod over her shrinking shoulders all the day, and all the night to turn the wheel of false desire;" intolerable that she should be driven by "longings that wake her womb" to bring forth not men but some monstrous "abhorred birth of cherubs," imperfect, artificial, abortive; counterfeits of holiness and mockeries of purity; things of barren or perverse nature, creatures inhuman or diseased, that live as a pestilence lives and pass away as a meteor passes; "till the child dwell with one he hates, and do the deed he loathes, and the impure scourge force his seed into its unripe birth ere yet his eyelids can behold the arrows of the day:" the day whose blinding beams had surely somewhat affected the prophet's own eyesight, and left his eyelids lined with strange colours of fugitive red and green that fades into black. However, all these things shall be made plain by death; for "over the porch is written Take thy bliss, man! and sweet shall be thy taste, and sweet thy infant joys renew." On the one hand is innocence, on the other modesty; infancy is "fearless, lustful, happy;" who taught it modesty, "subtle modesty, child of night and sleep?" Once taught to dissemble, to call pure things impure, to "catch virgin joy, and brand it with the name of whore and sell it in the night;" once corrupted and misled, "religious dreams and holy vespers light thy smoky fires: once were thy fires lighted by the eyes of honest morn." Not pleasure but hypocrisy is the unclean thing; Oothoon is no harlot, but "a virgin filled with virgin fancies, open to joy and to delight wherever it appears; if in the morning sun I find it, there my eyes are fixed in happy copulation:" and so forth—further than we need follow.

Is it because acts are not lovely that thou seekest solitude

Where the horrible darkness is impressed with reflections of desire?—

Father of Jealousy, be thou accursed from the earth!

Why hast thou taught my Theotormon this accursed thing?

Till beauty fades from off my shoulders, darkened and cast out,

A solitary shadow wailing on the margin of non-entity;"

as in a later prophecy Ahania, cast out by the jealous God, being the type or embodiment of this sacred natural love "free as the mountain wind."

Can that be love which drinks another as a sponge drinks water?

That clouds with jealousy his nights, with weepings all the days?

* * * * * *

Such is self-love, that envies all; a creeping skeleton

With lamp-like eyes watching around the frozen marriage-bed."

But instead of the dark-grey "web of age" spun around man by self-love, love spreads nets to catch for him all wandering and foreign pleasures, pale as mild silver or ruddy as flaming gold; beholds them without grudging drink deep of various delight, "red as the rosy morning, lustful as the first-born beam." No single law for all things alike; the sun will not shine in the miser's secret chamber, nor the brightest cloud drop fruitful rain on his stone threshold; for one thing night is good and for another thing day: nothing is good and nothing evil to all at once.

'The sea-fowl takes the wintry blast for a covering to her limbs,

And the wild snake the pestilence, to adorn him with gems and gold;

And trees and birds and beasts and men behold their eternal joy.

Arise, you little glancing wings, and sing your infant joy!

Arise and drink your bliss! For everything that lives is holy.'

Thus every morning wails Oothoon, but Theotormon sits

Upon the margined ocean, conversing with shadows dire.

The daughters of Albion hear her woes, and echo back her sighs."

It may be feared that Oothoon has yet to wait long before Thetoormon will leave off "conversing with shadows dire;" nor is it surprising that this poem won such small favour; for had it not seemed inexplicable it must have seemed unbearable. Blake, as evidently as Shelley, did in all innocence believe that ameliorated humanity would be soon qualified to start afresh on these new terms after the saving advent of French and American revolutions. "All good things are in the West;" thence in the teeth of "Urizen" shall human deliverance come at length. In the same year Blake's prophecy of America came forth to proclaim this message over again. Upon this book we need not dwell so long; it has more of thunder and less of lightning than the former prophecies; more of sonorous cloud and less of explicit fire. The prelude, though windy enough, is among Blake's nobler myths: the divine spirit of rebellious redemption, imprisoned as yet by the gods of night and chaos, is fed and sustained in secret by the "nameless" spirit of the great western continent; nameless and shadowy, a daughter of chaos, till the day of their fierce and fruitful union.

Silent as despairing love and strong as jealousy,

The hairy shoulders rend the links, free are the wrists of fire."

At his embrace "she cast aside her clouds and smiled her first-born smile, as when a black cloud shows its lightnings to the silent deep."

Soon as she saw the terrible boy then burst the virgin's cry;

I love thee; I have found thee, and I will not let thee go.

Thou art the image of God who dwells in darkness of Africa,

And thou art fallen to give me life in regions of dark death."

Then begins the agony of revolution, her frost and his fire mingling in pain; and the poem opens as with a sound and a light of storm. It is throughout in the main a mere expansion and dilution of the "Song of Liberty" which we have already heard; and in the interludes of the great fight between Urizen and Orc the human names of American or English leaders fall upon the ear with a sudden incongruous clash: not perhaps unfelt by the author's ear also, but unheeded in his desire to make vital and vivid the message he came to deliver. The action is wholly swamped by the allegory; hardly is it related how the serpent-formed "hater of dignities, lover of wild rebellion and transgressor of God's Law," arose in red clouds, "a wonder, a human fire;" "heat but not light went from him;" "his terrible limbs were fire; "his voice shook the ancient Druid temple of tyranny and faith, proclaiming freedom and "the fiery joy that Urizen perverted to ten commands;" the "punishing demons" of the God of jealousy

|

"Crouch howling before their caverns deep like skins dried in the wind; |

"Thus wept the angel voice" of the guardian-angel of Albion; but the thirteen angels of the American provinces rent off their robes and threw down their sceptres and cast in their lot with the rebel; gathered together where on the hills

"called Atlantean hills,

Because from their bright summits you may pass to the golden world,

An ancient palace, archetype of mighty emperies,

Hears its immortal pinnacles, built in the forest of God

By Ariston the king of beauty for his stolen bride."

A myth of which we are to hear no more, significant probably of the rebellion of natural beauty against the intolerable tyranny of God, from which she has to seek shelter in the darkest part of his creation with the angelic or daemonic bridegroom (one of the descended "sons of God") who has wedded her by stealth and built her a secret shelter from the strife of divine things; where at least nature may breathe freely and take pleasure; whither also in their time congregate all other rebellious forces and spirits at war with the Creator and his laws. But the speech of "Boston's angel" we will at least transcribe: not without a wish that he had never since then spoken more incoherently and less musically.

|

"Must the generous tremble and leave his joy to the idle, to the pestilence, |

This is perhaps the finest and clearest passage in the book; and beyond this point there is not much extractable from the clamorous lyrical chaos. Here again besides the mere outward violence of battle, the visible plague and fire of war, we have sight of a subtler and wider revolution.

For the female spirits of the dead pining in bonds of religion

Run from their fetters reddening and in long-drawn arches sitting.

They feel the nerves of youth renew, and desires of ancient times."

Light and warmth and colour and life are shed from the flames of revolution not alone on city and valley and hill, but likewise

Over their pale limbs, as a vine when the tender grape appears;

* * * * * *

The heavens melted from north to south; and Orizen who sat

Above all heavens in thunders wrapt, emerged his leprous head

From out his holy shrine; his tears in deluge piteous

Falling into the deep sublime."