Yule Logs/The King of Spain's Will

THE KING OF SPAIN'S WILL

By JOHN BLOUNDELLE-BURTON

CHAPTER I

I CAN tell you there was a pretty bustle around Paris that night when the news came of the downfall of the old Fox—the fox being none other than Cardinal Alberoni, who had just been turned out of Spain for his intrigues, King Philip V. having had enough of him. Not that the man, who had been a gardener's son, and a sort of buffoon once to the Duke of Parma, was so wondrous old, since in this year of grace 1719 he was but fifty-five. Only, when a man is a scheming knave, who has passed his full prime, and is also a fox—why, one generally calls him an old one.

Now, the news of Alberoni's disgrace at Madrid came first to us at Versailles, just about four of the afternoon, what time we of the Grey Musketeers were going off duty, our place till midnight being taken by those of the cavalry regiment of Vermandois, which had arrived a week ago from Blois—came at the hands of the Comte St. Denis de Pile, who had been sent off post-haste to Paris with the information, and also with another piece of intelligence, at which, I protest, not one of us could help laughing, serious enough though the thing was. This news being none other than that the crafty old Italian, who was on his way to Marseilles, there to embark with all his wealth for his native land, had absolutely carried off in his possession the will of the late King of Spain, Charles II., in which he bequeathed his throne to the very man who now sat upon it.

"And," exclaimed St. Denis de Pile, as he drank down a flask of Florence wine which we produced for him in the guard-room, "I'll be sworn that he means to send that will to the Emperor of Austria, who, if he is not a fool, will at once destroy it. And then, poof! poof! poof!" and the Count blew out his moustache in front of his lip, "what becomes of all that we fought for in the War of the Succession? Tête de mon chien! it will have to begin all over again. Your countrymen, my boy," and he slapped me affectionately on the shoulder, for we had met often enough before, "your countrymen, the English, will want another war, King George may be willing enough to oblige them, and the Treaty of Utrecht may as well be used to light a fire."

Now here was what some of my countrymen call a pretty kettle of fish. Peace was expected to be proclaimed in Europe at this moment, since the war of the Pyrenees was over. France and England were sworn allies and bosom friends, otherwise be sure that I, an Englishman, young and enthusiastic, would not have been holding the commission of a cornet in the Musketeers, and serving the Regent, or, rather, the boy king for whom he ruled. And all in a moment it was just as likely as not that that war might break out again through the craftiness of the Cardinal, who, since he had fallen, evidently did not mean to do so without pulling others down with him. For Austria had never willingly resigned her claims on the throne of Spain, remembering that the old French King had once formally waived all the claims of his own family to it, Will or no Will, and had then instantly asserted them on the death of Charles; while for my country—well! we English are not over fond of retreating from anything we have undertaken, though, for widely-known considerations not necessary to set down here, we had at last agreed to that peace of Utrecht, our having thoroughly beaten the French by sea and land before we did so, being, perhaps, the reason why we at last came in.

"What's to be done?" said old D'Hautefeuille now, who was in command of the Grey Musketeers at this time.

"What? What? Le Débonnaire is at the Palais Royal—he must know the news at once. De Pile, you must ride on to Paris."

"Fichtre for Paris!" exclaimed the Count. "I am battered enough already with my long ride. Think on't—from Madrid! Through storms and burning suns, over mountains and through plains, over two hundred leagues and across half a score of horses' backs. Also, observe—the letter is inscribed to the Regent's Grace at Versailles. I have done my duty—"

"But—"

"No ‘buts,’ D'Hautefeuille. My work is done. Let the King's lieutenant of Versailles, who commands in his and the Regent's absence, take charge of the paper. For me a bottle and a meal, also a bed."

"Then take it to the lieutenant," said fiery D'Hautefeuille; "hand it to him yourself, and bid him find a courier to Paris. Peste! you, a royal messenger who can ride from Madrid here, and yet cannot finish the journey to Paris! Bah! go and get your bottle and your bed and much good may they do you."

Whereon the old fellow turned grumpily away, bidding some of the younger ones amongst us not to be loitering about the galleries endeavouring to catch the eyes of the maids of honour, but, instead, to get off to our quarters and be ready to relieve the officers of the Vermandois regiment at midnight.

Yet, one amongst us, at least, was not to hear the chimes of midnight summoning us to the night guard, that one being myself, as you shall see. Nay, not one hour later was to ring out from the palace clock ere, as luck would have it, I was called forth from my own quarters—or rather from the little salon of Alison de Prie (who was a maid of honour, and who had invited me in to partake of a pâté de bécasse which her father had sent her from his property near Tours) by an order to attend on D'Hautefeuille in his quarters.

Whereon I proceeded thither and found him in a very bad temper—a thing he suffered much from lately, since he also suffered from a gout that teased him terribly. Then, immediately, he burst out on my putting in an appearance.

"Now, Adrian Trent, it is your month of special service, is it not?"

"It is, monsieur," I answered, wondering what was coming next.

"So! very well. Here then is something for you to do—that is, if the turning of my officers into couriers and post-boys and lackeys constitutes ‘special service.’ However, three creatures have to obey orders in this world, soldiers, wives, and dogs, therefore I—and you—must do so. Here, take this," and he tossed to me across his table a mighty great letter on which was a formidable red seal—"have your horse saddled and be off with you to Paris. Give it into the Regent's hand. It is the account of Alberoni's disgrace which that fainéant De Pile could bring all this way, but no farther. Away with you! The King's lieutenant seems to think that De Pile is discharged of his duty here. Away with you! What are you stopping for? You know the road to Paris, I suppose? You ought to. It's hard enough to keep you boys out of it if I give you an afternoon's leave. Be off!"

So off I went, and five minutes afterwards my best grey, La Rose, was saddled, and I was riding swiftly towards where the Regent was at the present moment.

Now, who'd have thought when I went clattering through Sévres and Issy, on that fine winter afternoon, in all the bravery of my full costume—which was the handsomest of any regiment in France, not even excepting our comrades of the Black Musketeers—who'd have thought, I say, that I was really taking the first steps of a long, toilsome journey, which, ere it was ended, was to bring me pretty near to danger and death? However, no need to anticipate, since those who read will see.

An hour later I was in Paris, and then, even as I went swiftly along amidst the crowds that were in the streets, especially in those streets round about the Palais Royal, I found that one thing was very certain, namely, that though I might be now carrying on De Pile's message from the Court of Spain to the Court of France, the purport of it was already known. Near the Palais Royal were numerous groups gathered, who cheered occasionally for France and England, which did me good to hear; then for Spain and France, which did not move me so much; while, at the same time, I distinctly heard Alberoni's name mentioned, with, attached to it, expressions and epithets that were anything but flattering. Also, as I made for the entrance opposite the Louvre, people called attention to me, saying, "Voila le beau Mousquetaire—chut! doubtless he rides from Versailles. Brings confirmation of the old trickster's downfall. Ho! le beau Mousquetaire." While a strident-voiced buffoon cried out to me, asking if all my gold galloon and feathers and lace did not sometimes get spoilt by the damp of the wintry weather, and another desired to know if my sweetheart did not adore me in my regimental fallals?

However, La Rose made her way through them all, shaking her bridle-chain angrily if any got before her, breathing out great gusts from her fiery nostrils, and casting now and again the wicked white of her eye around; she was a beauty who loved not to be pestered or interfered with. And at last I was off her back, at the door near the Regent's apartments on the south side, and asking for the officer of the guard; and half-an-hour later I was in the presence of the Regent himself, who sat writing in a little room about big enough to make a cage for a bird. Yet, in spite of the way in which his Highness spent his evenings and nights, and also of his supper parties and other dissipations, he did as much work in that little cabinet as any other twelve men in France.

Because he was a very perfect gentleman—no matter what his faults were (he answered for them to his Maker but a little while after I met him)—he treated me exactly as though I were his equal, and bade me be seated while he read the letter calmly; then, looking up at me, he said—

"I knew something of this before. Even my beloved Parisians know of it—how they have learnt it Heaven alone can say. Still it is known. Alberoni was to leave Madrid in forty-eight hours from the time of receiving notice. But—"

Here he paused, and seemed to be reflecting deeply. Then he said aloud, though more to himself than to me, "I wonder, if he has got the will?"

It not being my place to speak, I said nothing, waiting to receive orders from him. And a moment later he again addressed me.

"You mousquetaires have always the best of horses and are proud of them. I know; I know. I have seen you riding races against each other at Versailles and Marly. And, for endurance, they will carry you far, both well and swiftly, in spite of your weight and trappings. Is it not so?"

"It is so, monseigneur," I answered, somewhat wonderingly, and not quite understanding what way this talk tended.

"How fast can you go? Say—a picked number of you—ten—twenty—go for two days?"

"A long way, monseigneur. Perhaps, allowing for rest for the animals, nearer forty than thirty leagues."

"So! Nearer forty than thirty leagues. 'Tis well."

Here he rose from his chair (I, of course, rising also), turned himself round, and gazed at a map of France hanging on the wall; ran, too, his finger along it from the Pyrenees in the direction of Marseilles, while, as he did so, he muttered continually, yet loud enough to be quite audible to me—

"He would cross there—there, surely. Fifteen days to quit Spain, two to quit Madrid—seventeen altogether.

"Ran his finger along a map of France."

From the fifth. The fifth! This is the twelfth. Ten days still."

Then he continued to run his finger along the coast line of the Mediterranean until it rested on Marseilles, at which he stood gazing for some time. But now he said nothing aloud for me to listen to, though it was evident enough that he was considering deeply; but at last he spoke again.

"His Eminence must be met and escorted—yes, escorted—that is it—escorted in safety through the land. Ay, in safety and safely. He must not be molested nor—" while, though he turned his face away to gaze at the map again, I would have been sworn that I heard him mutter—"allowed to depart quite yet." Then he suddenly said, "Do you know the house of the Chevalier de Marcieu? It is in the Rue des Mauvais Garçons."

"I know the street, monseigneur. I can find the house."

"Good! Therefore proceed there at once—the number is three—you are mounted, of course? Give my orders to him that he is to come here instantly; then return and I will give you some instructions for your commander."

Whereon I bowed respectfully as I went to the door, the Regent smiling pleasantly upon me. Yet, ere I left him, he said another word, asked a question.

"You mousquetaires gris have not had much exercise lately at Versailles, I think. Have you?"

"No, monseigneur, not our troop at least. The men have been but recently remounted."

"So. Very well. You shall have some exercise now. 'Twill do you good. You shall have a change of billet for a little while. In any case, Versailles is too luxurious a place for soldiers. Now, away with you to Marcieu's house and bid him come here. Return also yourself. Forget not that."

CHAPTER II

A GIRL CALLED DAMARIS

A week later, or, to be exact, six days, and the troop of Grey Musketeers, commanded by Captain the Vicomte de Pontgibaud—which was the one in which I rode as cornet—was making its way pleasantly enough along the great southern road that runs down from Paris to Toulouse. Indeed, we were very near that city now, and expected to be in it by the time that the wintry evening had fallen. In it, and safely housed for the night, not forgetting that the suppers of Southern France are most excellent and comforting meals, and that the Lunel and Roussillon are equally suited to the palate of a soldier, even though that soldier be but twenty years old; as I was in those days, now, alas! long since vanished.

But, ere I go on with what I have to tell, perhaps you would care to hear in a few words how I, Adrian Trent, an Englishman, am riding as cornette or porte drapeau in a corps d'élite of our old hereditary enemies, the French. Well, this is how it was. The Trents have ever been Royalists, by which I mean that they and I, and all of our thinking, were followers of the House of Stuart. Now, you who read this may be one of those—or your father may have been one of those—who invited the Elector of Hanover to come over and ascend the English throne, or you may be what my family and I are at the present moment, Jacobites. Never mind for that, however. You can keep your principles and we will keep ours, and need not quarrel about them. Suffice it, therefore, if I say that our principles have led us to quit England and to take up our abode in France. And if ever King James III. sits on— However, no matter for that either; it concerns not this narrative.

My father was attached to the court of this King, who was just then in temporary residence in Rome—though, also, he sojourned some time in Spain—but, ere he followed his sovereign's errant fortunes, he obtained for me my guidon in the Musketeers, which service is most agreeable to me, who, from a boy, had sworn that I would be a soldier or nothing; while, since I cannot be an English one, I must, perforce, be in the service of France. And, as I trust that never more will France and England be flying at each other's throats, I do hope that I may long wear the uniform of the regiment. If not— But of that, too, we will not speak.

To get on with what I have to tell, we rode into Toulouse just as the winter day was coming to an end, and a brave show we made, I can assure you, as we drew up in the great courtyard of the old "Taverne du Midi," a place that had been the leading hostelry ever since the dark ages. For in that tavern, pilgrims, knights on their road to Rome and even the Holy Land, men of different armies, wandering minstrels and troubadours, had all been accustomed to repose; even beggars and monks (who paid for nothing) could be here accommodated, if they chose to lie down in the straw amongst the horses and sing a good song in return for their supper.

And I do protest that, on this cold December night, when the icicles were hanging a foot long from the eaves, and bitter blasts were blowing all around the city—the north-east winds coming from away over the Lower Alps of Savoy—you might have thought that you were back again in those days, if you looked around the great salle-à-manger of the tavern. For in that vast room was gathered together a company which comprised as many different kinds of people as any company could have consisted of when met together in it in bygone ages. First, there was the nobleman who, because he was one, had had erected round his corner a great screen of arras by his domestics; such things being always carried in France by persons of much distinction, since they could neither endure to be seen by the commoner orders, nor, if they had private rooms, could they endure to look upon the bare whitewashed walls of the rooms, wherefore the arras was in that case hung on those walls. This great man we did not set eyes on, he being enshrouded in his haughty seclusion, but there was plenty else to be observed. Even now, in these modern days of which I write, there were monks, travellers, a fantoccini troupe, some other soldiers besides ourselves, they being of the regiment of Perche, the intendant of the solitary lord, and ourselves. Our troopers alone numbered twenty, they having a table to themselves; while we, the officers, viz., the captain (De Pontgibaud), the lieutenant (whose name was Camier), and I (the cornet), had also a table to ourselves.

Yet, too, there was one other, and, if only from her quaint garb, a very conspicuous person. This was a girl—and a mighty well-favoured girl too—dark, with her hair tucked up all about her head; with superb full eyes, and with a colour rich and brilliant as that of the Provence rose. She made good use of those eyes, I can tell you, and seemed nothing loth to let them encounter the glance of every one else in the room. For the rest, she was a sort of wandering singer and juggler, clad in a short spangled robe, carrying a tambour de basque in her hand, while by her side hung a coarse canvas bag, in which, as we soon saw, she had about a dozen of conjuring balls.

"Who is that?" asked De Pontgibaud of the server, as he came near our table bearing in his hand a succulent ragôut, which was one of our courses—"who and what? A traveller, or a girl belonging to Toulouse?"

"Oh!" said the man, with the true southern shrug of his shoulders, "that!—elle! She is a wandering singer, a girl called Damaris. On her road farther south. Pray Heaven she steals nothing. She is as like to if she has the chance. A purse or even a spoon, I'll wager. If I were the master she should not be here. Yet, she amuses the company. Sings love ballads and such things, and juggles with those balls. Ha! giglot," he exclaimed, seeing the girl jump off the table she had been sitting on, talking to a bagman, and come towards us, "away. The gentlemen of the mousquetaires require not your company."

"Ay, but they do though," the girl called Damaris said, as she drew close to where we sat. "Soldiers like amusement, and I can amuse them. Pretty gentlemen," she went on, "would you like a love song made in Touraine, or to see a trick or two? Or I have a snake in a box that can do quaint things. Shall I go fetch it—it will dance if I pipe——"

"To confusion with your snake!" exclaimed the waiting man, "we want no snakes here. Snakes, indeed——!"

"Well, then, a love song. This pretty boy," and here she was forward enough to fix her eyes most boldly on me, "looks as if he would like a love song. How blue his eyes are!"

Alas! they are somewhat dim and old now, but then, because I was young and foolish, and because my eyes were blue, I felt flattered at this wandering creature's remark. However, without waiting for an answer, she went on.

"Come, we will have a trick first. Now," she said, pulling out three of the balls from her bag, "you hold that ball, mon enfant—thus," and she put one red one—the only red one—into my hand. "You have it?"

"Yes," I said, "I have it;" and, because it was as big as a good-sized apple, I closed my two hands over it.

"You are sure?"

"Certain."

"Show it then." Whereon I opened my hands again, and, lo! it was a gilt ball and not a red one that was in them.

"Show that trick to me," said a voice at my back, even as De Pontgibaud and Camier burst out a-laughing, and so, too, did some of the people in the great hall who were supping, while I felt like a fool. "Show that trick to me." And, looking round, I saw that it was the Chevalier de Marcieu who had spoken; the man to whom the Regent had sent me, and who had ridden from Paris with us as a sort of civilian director, or guide; the man from whom we were to take our orders when acting as guard to Alberoni when he passed this way, presuming that we had the good fortune to encounter his Eminence; he who was to be responsible for the safety of the Cardinal.

Now, he knew well enough that we of the mousquetaires gris did not like him, that we regarded him as a spy—which, in truth, he was, more or less—and that his company was not absolutely welcome to us. Wherefore, all along the road from Paris he had kept himself very much apart from us, not taking his meals at our table—where he was not wanted!—and riding ever behind the troop, saying very little except when necessary. But now he had evidently left the table at which he ate alone and had come over to ours, drawn there, perhaps, by a desire to witness the girl's performances.

"No," she said, "I shall not show it to you. I do not do the same trick twice. But, if you choose, I will fetch my little snake. Perhaps that would amuse you."

"I wish to see that trick with the red ball," said De Marcieu quietly, taking no notice whatever of her emphasis on the word "you." "Show it to me."

For answer, however, she dropped the balls into the bag, and, drawing up a vacant chair which stood against our table—she was a free and easy young woman, this!—said she was tired, and should do no more tricks that night. Also, she asked for some of our Roussillon as a payment for what she had done. Whereupon Camier poured her out a gobletful and passed it over to her, which, with a pretty little bow and grimace, she took, drinking our healths saucily a moment later.

Meanwhile I was eyeing this stroller and thinking that she was a vastly well-favoured one in spite of her brown skin, which, both on face and hands, was a strange colour, it not being altogether that wholesome, healthy brown which the winds and sun bring to those who are always in the open, but, instead, a sort of muddy colour, so that I thought, perhaps, she did not use to wash overmuch—which, maybe, was like enough. Also, I wondered at the shapeliness of her fingers and hands, the former being delicate and tapering, and the nails particularly well kept. Likewise, I observed something else that I thought strange. Her robe—for such it was—consisted of a coarse, russet-coloured Nîmes serge, such as the poor ever wear in France, having in it several tears and jags that had been mended roughly, yet, all the same, it looked new and fresh —too new, indeed, to have been thus torn and frayed. Then, also, I noticed that at her neck, just above the collar of her dress, there peeped out a piece of lace of the finest quality, lace as good as that of my steinkirk or the ruffles of a dandy's frills. And all this set me a-musing, I know not why.

Meanwhile Marcieu was persistent about that red ball, asking her again and again to try the trick on him, and protesting in a kind of rude good-humour that she did not dare to let him inspect the ball, since she feared he would discover some cunning artifice in it which would show how she made it change from red to gilt.

"Bah!" she replied, "I can do it with anything else. Here, I will show you the trick with other balls." Whereon, as she spoke, she drew out two of the gilt ones and said, "Now, hold out your hands and observe. See, this one has a scratch on it; that one has none. Put the second in your hand and I will transfer the other in its place."

"Nay," said the chevalier; "you shall do it with the red or not at all."

"I will conjure no more," she said pettishly. Then she snatched up the goblet of wine, drank it down at a gulp, and went off out of the room, saying—

"Good-night, mousquetaires. Good-night, Blue Eyes," and, I protest, blew me a kiss with the tips of her fingers. The sauciness of these mountebanks is often beyond belief.

The chevalier took the vacant chair she had quitted, though no one invited him to do so, his company not being desired by any of us, and Pontgibaud, calling for a deck of cards, challenged Camier to a game of piquet. As for me, I sat with my elbows on the table watching them play, though at the same time my eye occasionally fell on the spy, and I wondered what he was musing upon so deeply. But, presently, he called the drawer over to him and gave an order for some drink to be brought (since none of us had passed him over the flask, we aristocratic mousquetaires not deeming a mouchard fit bottle-companion for us), and when it came he turned his back to the table at which we sat, and asked the man a question in a low voice; though not so low a one but that I caught what he said, and the reply too.

"Where is that vagrant disposed of?" he asked. "With those other vagabonds, I suppose," letting his eye fall on the members of the fantoccini troupe, "or in one of the stables."

"Nay, nay," the server said, "she is not here, but at the ‘Red Glove’ in the next street. She told me to-night that that was her headquarters until she had visited every inn and tavern in Toulouse and earned some money. Then she will go on to Narbonne."

"So! The ‘Red Glove.’ A poor inn that, is it not?"

Whereon the man said it was good enough for a wandering ballad-singer anyhow, and went off swiftly to attend to another order at the end of the room, while Marcieu sat there sipping his drink, but now and again casting his eye also over some tablets which he had drawn out of his pocket.

But at this time nine o'clock boomed forth from the tower of the cathedral hard by, which we had noticed as we rode in, and Pontgibaud gave the troopers their orders to betake themselves to their beds; also one to me to go to the stables and see that all the horses were carefully bestowed for the night, since, though the troop-sergeant had made his report that such was the case, he required confirmation of it. Wherefore I went to the end of the room, and, taking my long grey houppelande, or horseman's cloak (which we mousquetaires, because we always had the best of everything, wore trimmed with costly grey fur), I donned it, and was about to go forth to the stables when I heard Pontgibaud's voice raised somewhat angrily as he spoke to the chevalier.

"We are soldiers, not——"

"Fichtre for such an arrest!" I heard him say, while the few strangers who had not gone to their beds—as most had done by now—cast their eyes in the direction where he and Marcieu were. "Not I! Body of my father! what do you take my gentlemen of the mousquetaires to be? Exempts! police! Bah! Go to La Poste. Get one of their fellows to do it. We are soldiers, not——"

"I have the Regent's orders," Le Marcieu replied quietly, "to arrest him or any one else I see fit. And, Monsieur le Vicomte, it is to assist me that your ‘gentlemen of the mousquetaires’ are here in Toulouse—have ridden with me from Paris. I must press it upon you to do as I desire."

Now, I could not wait any longer, since I had my orders from Pontgibaud to repair to the stables and see that the chargers were comfortable for the night, and as, also, I saw a glance shoot out of his eye over the other's head which seemed to bid me go on with my duty. Upon which I went out to the yard, noticing that the snow was falling heavily, and that it was like to be a hard winter night—went out accompanied by a stableman carrying a lantern.

"Give it me," I said, taking the lamp from him, "I will go the round myself. Also the key, so that I can lock the door when I have made inspection."

"Nay, monsieur," he answered, "the door cannot be locked. The inn is full; other travellers' horses are in the stable; they may be required at daybreak."

"Very well," I replied, "in that case one of our men must be roused and put as guard over the animals; they are too valuable to be left alone in an open stable," and, as I spoke, I thought particularly of my beautiful La Rose, for whom I had paid a hundred pistoles a year ago. Then I gave the fellow a silver piece and bade him go get a drink to warm himself with on this winter night, and entered the stable.

The whinny which La Rose gave as I went in showed me where all our horses were bestowed, and I proceeded down to the end of the stable, observing when I got there that they were all well housed for the night, and their

"Not so fast, mademoiselle, not so fast. What are you doing here?"

Then suddenly, as I raised the lantern to give a second glance at it, to my astonishment I saw the singing-girl, Damaris, dart out swiftly from near that stall and endeavour to push by me and escape through the door; which, however, I easily prevented her from doing, since I seized her at once by the arm and held her, while I exclaimed, "Not so fast, mademoiselle, not so fast. What are you doing here?—you, who are at the ‘Red Glove’ and have no business whatever in these stables."

CHAPTER III

"WHEN THE STEED HAS FLOWN"

At first she struggled a little, then all of a sudden she took a different tack, and exclaimed, "How dare you touch me, fellow. You—a common mousquetaire—to lay your hands on me! You! you! Let go—or——"

However, I had let go of her by now through astonishment at her impertinence. A common mousquetaire, indeed!—a common mousquetaire!—when, in all our regiment, there was scarce a trooper riding who was not of gentle blood—to say nothing of the officers.

"I may be ‘a common mousquetaire,’" I replied, as calmly as I could, "yet, all the same, commit no rudeness to a wandering ballad-singer whom I find in the stable where our horses are; and——"

"Why!" she exclaimed, with a look (I could see it by the rays of the lantern) that was, I'll be sworn, as much a pretence as her words—"why ! 'tis Blue Eyes. Forgive me; I thought it was one of your men—I—I—did not know you in your great furred cloak. It becomes you vastly well, Blue Eyes," and the hussy smiled up approvingly at me.

"Does it?" I said. "No doubt. Yet, nevertheless, I want an explanation of what you are doing in these stables at night, in the dark, when you are housed at the 'Red Glove';" and I spoke all the more firmly because I felt certain that she had not taken me for one of the troopers at all.

"Imbecile!" she exclaimed petulantly, and for all the world as if she was speaking to an inferior. "Imbecile! Idiot! Since you know I am at the 'Red Glove,' don't you know too that they have no stabling for us who put up there, and that the travellers' cattle are installed here? Oh, Blue Eyes, you are only a simple boy!"

"No, I don't know it!" I exclaimed, a little dashed at this intelligence;" but, pardon me, I would not be ill mannered—only—do ladies of your calling travel on horseback? I thought you wandered on foot from town to town giving your entertainments."

"I do not travel on horseback, but on muleback. There are such things as four-footed mules as well as two-footed ones, Blue Eyes. I assure you there are. And here is mine; look at it. Isn't it a sorry beast to be in company with the noble steeds of the aristocratic mousquetaires?"

"Oh, it's 'aristocratic' now, is it?" I thought to myself, "not 'common' mousquetaires," running my eye over the mule she pointed out, even as I held the lantern on high. Only, as I did so, I saw it was not a sorry beast at all; instead, a wiry, clean-limbed Pyrenean mule, whose hind-legs looked as though they could spring forward mighty fast if wanted; in truth, an animal that looked as if it could show its heels to many of its nobler kin, namely horses. But, also, I observed that its saddle was on, and that the halter was not fastened to the rack.

"Well, you see?" she said, looking at me with her mocking smile, and showing all her pretty white teeth as she did so. "You see? Now, Blue Eyes, let me go. I am tired and sleepy, and I want to go to bed."

This being sufficient explanation of her presence in the stables, there was no further reason why I should detain her and I said she might go, while, even as I spoke, I fastened up the halter for her. After which we went out into the yard, where we bade each other a sort of good-night, I doing so a little crossly since I was still sore at her banter, and she, on her part, speaking in still her mocking, gibing manner.

"And where do you go to," she asked, "after this? Eh, Blue Eyes? I should like to see you some day again, you know. I like you, Blue Eyes," and as she spoke I wondered what impish kind of thought was now in her mind, for she was standing close to me, and seemed to be emphasising her remarks about her liking for me by clutching tight my houppelande in her hand.

" That," I said, "is, if you will excuse me, our affair. Good-night; I hope you will sleep well at the 'Red Glove.'" Then, because I did not want to part in anger from the volatile creature, and because I was a soldier to whom such licence is permissible, I said, "Adieu, sweetheart."

"Sweetheart!" she exclaimed, turning round on me. "Sweetheart! You dare to speak to me thus—you—you—you base—" But, just as suddenly as she had flown out at me like a spitfire, she changed again, saying, "Peste! I forget—I am only a poor wandering vagrant. I did not mean that. I—I am sorry." And, as she vanished round the corner of the yard into the street, I heard her laugh and say softly, though loud enough, "Good-night, Blue Eyes; adieu—sweetheart;" and again she laughed as she disappeared.

Now, all this had taken some little time, as you may well suppose, so that the great clock of the Cathedral of St. Etienne was striking ten as I re-entered the inn and went on to the large guests'-room, or salle. It was empty at this time of all the sojourners in the house, except the captain, Pontgibaud, who was sitting in front of the huge fire, into which he stared meditatively while he drank some wine from a glass at his elbow.

"All well with the horses?" he asked, as I went up to him. "I thought you were never coming back." Then, without waiting for any explanation from me as to my absence, he said, "We go towards the Pyrenees, by Foix, to-morrow, thereby to intercept Alberoni if we can. That fellow, that mouchard, Marcieu, says he is due to cross into France from Aragon. Meanwhile—" but there he paused, saying no more. Instead, he gazed into the embers of the fire; then suddenly, a moment or so after, spoke again. "Adrian," he said, "it is fitting I should tell you what Marcieu knows, or rather suspects, from information he has received from Dubois, who himself has received it from Madrid. Camier has been informed; so must you be."

"What is it now?" I asked, my anxiety aroused.

"This. Alberoni, as Marcieu says, has all the old Spanish aristocracy on his side, simply because the King, Philippe, is a Frenchman. They are helping him—especially the ladies. Now, it is thought one of them has carried off the will of the late King Charles, and not Alberoni himself."

"Who is she?"

"He, Marcieu, will not tell, though he knows her rank and title. But—" and now Pontgibaud looked round the room, which was, as I have said, quite empty but for us, then lowered his voice ere he replied—"but—he is going to arrest that girl called Damaris to-morrow morning," and as he spoke he delivered himself of a grave, solemn wink.

"Is he?" I said; "is he?" and then fell a-musing. For this opened my eyes to much—opened them, too, in a moment. Now, I understood her indignation at a mousquetaire seizing hold of her, a high-born damsel, probably of some old Castile or Aragon family, instead of a wandering stroller as we had thought her to be—understood, too, why I had seen that piece of rich lace peeping out at her throat; why her dress of Nimes serge, which was a new one, was artfully torn and frayed. Also I understood, or thought I did, the strange colour of her face and hands, which were, I now made no manner of doubt, dyed or stained to appear dirty and weatherbeaten, and why the saddle was on her mule's back and the halter loose from the rack;—understood, I felt sure, all about it. Then, just as I was going to tell Pontgibaud this, we both started to our feet. For, outside, where the stables were, we heard a horse's hoofs strike smartly on the cobble-stones of the yard; we heard the animal break into a trot the moment it was in the street outside.

"Some one has stolen a horse from those stables," cried Pontgibaud, springing towards the door and rushing down the passage; "pray Heaven 'tis not one of our chargers."

To which I answered calmly, "I think not. There are other animals there than ours, horses and mules belonging to people staying at other inns. It is a traveller setting forth before the city gates are closed at midnight."

And, even as I spoke, I could not help laughing in my captain's face, as well as at the look upon it.

CHAPTER IV

ANA, PRINCESA DE CARBAJAL

We were riding through one of the innumerable valleys which are formed by the spurs of the Pyrenees running almost from where the Pic du Midi rises up to the city of Toulouse; a valley which was bordered on either side by shelving hills that were covered with woods nearly up to their summits. And now we were looking forward eagerly to meeting his Eminence, the Cardinal Alberoni, of whose arrival in this neighbourhood we had received certain intelligence from more than one of the innumerable spies whom both the Regent and Cardinal Dubois maintained ever in this region—a region dividing Spain from France.

As for Marcieu, who, as usual, rode behind the troop, he had been in such a towering rage ever since the morning of our departure from Toulouse, and had used such violent language, that I for one had been obliged to tell him to keep a civil tongue in his head, while Pontgibaud, who was an aristocrat to the tips of his fingers as well as captain of a troop of mousquetaires, told him he must be more respectful in his language or altogether silent. For, as naturally you have understood, it was the girl who was pleased to call herself Damaris, and to assume the disguise of a wandering juggler and singer, who had ridden off that night on her mule, and was, no doubt, far enough away from us in the morning.

And she had got the late King of Spain's will in her pocket! of that Marcieu swore there could be no doubt—the will which, in truth, was the principal thing that brought the nations to agreeing that the Duke of Anjou should sit as King Philippe V. on the throne of Spain—the will which, if it once fell into the hands of Austria, would instantly disappear for ever and set all Europe alight with the flames of war again. She had got it, and when Alberoni was searched it would not be found. Perhaps, after all, it was not strange that Marcieu's expressions were writ in a good round hand. He had missed the chance of his life!

"I know her," he stormed in the morning, when he found how abortive his attempts to arrest her had proved, "I know her. Dubois sent me intelligence of everything. She is the Princesa Ana de Carbajal, of an ancient and illustrious Catalonian house, a house faithful to all the interests of Austria before the days of Charles V. and of Philip. May the pest seize her! She came ahead of Alberoni disguised thus, and never thought she would encounter us. And I do believe she has the will in that accursed red ball. Such things have been used as hiding-places before. Even Alberoni once used his crook as a receptacle wherein to hide a slip of paper. And the late King's last will in favour of Philippe was itself but a slip of paper, signed when he was close to death." Then, again, he used strong language.

However, she was gone, and, on the frail chance of his being misinformed after all, and because he also had orders to meet Alberoni in any circumstances, and to escort him to the Mediterranean coast without allowing him to hold converse with any one, we set off to find him. For Dubois' spies had met us and said that Alberoni was on his way, that he was close at hand.

So we rode along, nearing rapidly the pass into Spain by which he was coming, and expecting every moment to meet the Cardinal's coach attended by all his servants and following. But suddenly, while we marched, there happened something which put all thoughts of the Cardinal and his devoted friend, the Princess Ana, out of our heads—something terrible—awful—to behold.

A house, an inn, on fire, blazing fiercely, as we could see, even as we all struck spurs into our horses and galloped swiftly towards it—a house from the upper windows of which we could observe the faces of people looking. The upper windows, because all the lower part was in flames, and because they who were inside had all retreated up and up and up. Only, what could that avail them! Soon the house, the top floor—there were two above the ground—must fall in and—then! Yes—then!

We reached that burning auberge—'twas terrible, ghastly, to see the flames bursting forth from it in the broad daylight and looking white in the glare of the warm southern sun, although 'twas winter—reached it, wondering what we could do to save those who were perishing; to save the screaming mother with her babe clasped to her breast, the white-faced man who called on God through the open window he was at to spare him and his, or, if not him, then his wife and child.

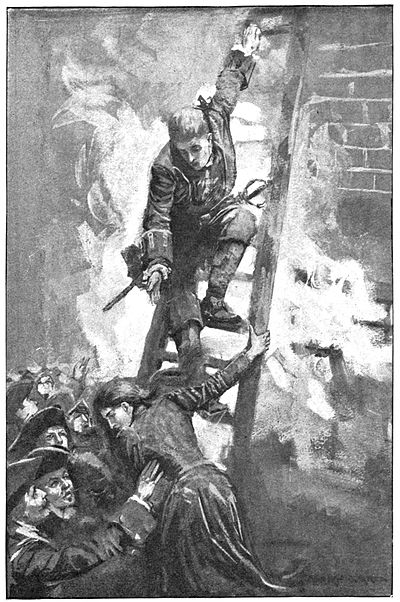

What could we do—what? Bid them leap down to us, fling themselves upon us—yes, at least we might do that. One thing at least we could undoubtedly do—bid them throw down the babe into our arms. And this was done. The troopers sat close upon their horses, their arms extended; a moment later the little thing was safe in the great strong arms of the men, and being caressed and folded to the breast of our great brawny sergeant. Then, even as I witnessed this, even, too, as I (dismounted now) hurried round with some mousquetaires to discover if, in God's mercy, there was any ladder behind in the outhouse or garden whereby the upper part might be reached, I myself almost screamed with horror; for, at that moment, on to the roof there had sprung a woman shrieking; a woman down whose back fell coils of long black hair; a woman, handsome, beautiful, even in her agony and fear; a woman who was the girl called Damaris.

"Damaris!" I called out, "Damaris!" for by that name I had come to think of her, had known her for a short hour or so, "Damaris! be calm, do nothing rash. We will save you; the walls will not fall in yet. Be cool." But in answer to my words she could do nothing but wring her hands and shriek.

"I cannot die like this—not like this. Oh, Blue Eyes, save me! Save me! Save me! You called me your sweetheart. Save me!"

Then, at that moment, I heard a calm, icy voice beside me say—it was the voice of Marcieu—"Does your highness intend to restore the late King of Spain's will? Answer that, or I swear, since I command here, that you shall not be saved."

In a moment I had sprung at him, would have pulled him off his horse, have struck him in the mouth, have killed him for his brutality, but that Camier and two of the troopers held me back, and, even as they did so, I heard the girl's voice ring out, "Yes! yes! yes! 'tis here;" while, as she spoke, she put her hand in the bag by her side, drew out the red ball, and flung it down from the roof to where we all were.

But by now, Heaven in its mercy be praised! some of the others had found a ladder and brought it round, and were placing it against the walls. Only, it was too short! God help her! it but reached to the sill of the top-floor window.

And now I was distraught, was mad with grief and horror, when again that cold-blooded creature, Marcieu, spoke, saying, "What matter? can she not descend from the roof to the room that window is in?" and at the same moment Pontgibaud called out to her to do that very thing, which she, at once understanding, prepared to accomplish.

Meanwhile, some of the men, who were all now dismounted, had sprung to the ladder, eager to save, first the girl, I think, then next the woman of the house, and then the man. But I ordered them back. I alone would save her, I said, I alone. Princess or stroller, noble or crafty adherent of a wronged monarchy, whichever she might be, I had taken a liking to this girl; she had called on me to save her, and I would do it. Wherefore, up the ladder I went as quickly as the weight of my great riding boots and trappings would permit me, while all the time the flames were shooting out from the lower windows—up, until I stood at the top one and received her in my arms, telling the woman and the man they should be saved immediately, which they were, the troopers fetching down the woman, and the man following directly after by himself; yet none too soon either, for, even as he came down, the flames had set the lower part of the ladder afire, so that it fell down and he got singed as he came to earth. But, nevertheless, all were now saved; and Damaris stood trembling by my side, and pouring out her thanks to, and blessings upon, me.

"I—I—did not mean what I said," stammered Marcieu. "I meant you should be saved. But I meant also to have that will, and I have got it." While, as his eye roved around us, he saw the disgust written upon all our faces, on the faces alike of officers and men.

"You have got it," she answered contemptuously. "You have! Much good may it do you, animal!" and again I saw the beautiful white teeth gleam between her lips.

"But why here, Dama-Señorita?" I whispered; "why here? You came the wrong way if you wished to escape with the precious document."

She gave me somewhat of a nervous, tremulous smile, and was about to answer me, and give me some explanation, when, lo! there came an interruption to all our talk. The long-expected Cardinal was approaching. Alberoni had crossed the Pyrenees.

But in what a way to come! We could scarcely

The Rescue.

"You are the man, I imagine, and those your troopers, whom Philippe the Regent has sent to intercept me. Ha! you are surprised that I know this," he went on, seeing the start that Marcieu gave when he heard those words. "Are you not? If you should ever know Alberoni better, you will learn that he is a match for most court spies in Europe."

Now the chevalier did seem so utterly taken aback at this (which caused Pontgibaud to give me a quaint look of satisfaction out of the tail of his eye—for every one of us hated that man mortally) that he could do nothing but bow, uttering no sound. Whereon the Cardinal proceeded:

"Well! What do you expect to do with me? Your comrades of Spain—the knaves and brigands whom the King sent after me from Madrid—have pillaged me of all. Some day I will pay his Majesty for the outrage—let him beware lest I place Austria back upon his throne. 'Twas a beggarly trick!—to take my carriages and mules, my jewels and wealth—even the will of the late King, which was most lawfully and rightfully in my possession."

"What!" broke from several of our lips, "what!" while from Marcieu's white and trembling ones came the words, "The late King's will! It is impossible. This girl—this lady—has handed it to me!"

For a moment the Cardinal's sly glance rested on the Princess, then on Marcieu, and then—then—he actually laughed, not loud, but long.

"Monsieur," he said at last, "you are a poor spy—easily to be tricked. You will never make a living at the calling. The will that lady gave you was a duplicate, a copy. It was meant that you should have that—that it should fall into your stupid hands. And, had I not been robbed on the other side of the mountains, you would not have seen me here."

"It is so," the Princess said, striding up to where the chevalier stood; "it is so. You spy! you spy! you mouchard! if that worthless piece of paper in the red ball had been the real will, I would have perished in the burning house before letting it fall into your hands." Then, sinking her voice still lower, though not so low but that some of us could hear what she said, she went on: "Have a care for your future. The followers of Austria have still some power left, even at the Court of France. Your threat to let me burn on the roof was not unmeant. It will be remembered."

And now there is no more to tell, except that the Princess knew that Marcieu meant to take the real will from the Cardinal if he met him, and so it had been arranged that, through her, the paper which he would suppose was that real will was to fall into his hands, and Alberoni would thus have been enabled to retain the original and escape with it out of France. She had preceded us to the foot of the mountains from Toulouse, meaning, when we came up, to let Marcieu obtain the red ball and thus be hoodwinked; and the accident of the fire at the inn only anticipated what she intended

"A friendship that eventually ripened—"

doing. The unexpected following of, and attack upon, the Cardinal, ere he quitted Spain and descended the Pyrenees into France, had, however, spoilt all their plans.

Here I should attempt that which most writers of narratives are in the habit of performing, namely, conclude by telling you what was the end of Ana de Carbajal's adventure, of how she won and broke hearts and eventually made a brilliant match. That is what Monsieur Marivaux or the fair Scuderi would have done, as well as some of the writers in my own native land. But I refrain, because this strange meeting between me and the beautiful and adventurous Spanish lady was but the commencement of a long friendship that eventually ripened—However, no matter. Some day, when my hand is not weary and the spirit is upon me, I intend to write down more of the history of the high-bred young aristocrat who first appeared before me as a wandering stroller, and passed for "a girl called Damaris."

![]()

This work was published before January 1, 1929, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse