A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Recitative

RECITATIVE (Ital. Recitativo; Germ. Recitativ, Fr. Récitatif; from the Latin recitare). A species of declamatory Music, extensively used in those portions of an Opera, an Oratorio, or a Cantata, in which the action of the Drama is too rapid, or the sentiment of the Poetry too changeful, to adapt itself to the studied rhythm of a regularly-constructed Aria.

The invention of Recitative marks a crisis in the History of Music, scarcely less important than that to which we owe the discovery of Harmony. Whether the strange conception in which it originated was first clothed in tangible form by Jacopo Peri, or Emilio del Cavaliere, is a question which has never been decided. There is, however, little doubt, that both these bold revolutionists assisted in working out the theory upon which that conception was based; for, both are known to have been members of that æsthetic brotherhood, which met in Florence during the later years of the 16th century, at the house of Giovanni Bardi, for the purpose of demonstrating the possibility of a modern revival of the Classic Drama, in its early purity; and it is certain that the discussions in which they then took part led, after a time, to the invention of the peculiar style of Music we are now considering. The question, therefore, narrows itself to one of priority of execution only. Now, the earliest specimens of true Recitative we possess are to be found in Peri's Opera, 'Euridice,' and Emilio's Oratorio, 'La Rappresentazione dell' Anima e del Corpo,' both printed in the year 1600. The Oratorio was first publicly performed in the February of that year, at Rome: the Opera, in December, at Florence. But Peri had previously written another Opera, 'Dafne,' in exactly the same style, and caused it to be privately performed, at the Palazzo Corsi, in Florence, in 1597. Emilio del Cavaliere, too, is known to have written at least three earlier pieces—'Il Satiro,' 'La Disperazione di Fileno,' and 'Il Giuoco della Cieca.' No trace of either of these can now be found: and, in our doubt as to whether they may not have contained true Recitatives, we can scarcely do otherwise than ascribe the invention to Peri, who certainly did use them in 'Dafne,' and whose style is, moreover, far more truly declamatory than the laboured and half rhythmic manner of his possible rival. [See Opera, vol. ii. 498–500; Oratorio, vol. ii. 534, 535.]

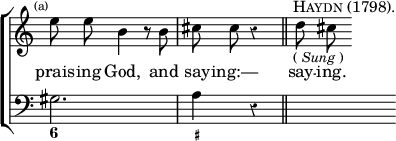

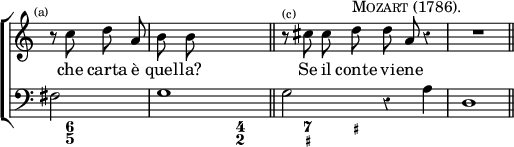

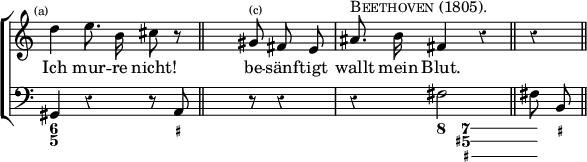

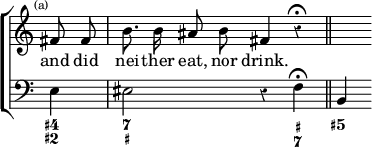

Thus first launched upon the world, for the purpose of giving a new impetus to the progress of Art, this particular Style of Composition has undergone less change, during the last 280 years, than any other. What Simple or Unaccompanied Recitative (Recitativo secco) is to-day, it was, in all essential particulars, in the time of 'Euridice.' Then, as now, it was supported by an unpretentious Thorough-Bass (Basso continuo), figured, in order that the necessary Chords might be filled in upon the Harpsichord, or Organ, without the addition of any kind of Symphony, or independent Accompaniment. Then, as now, its periods were moulded with reference to nothing more than the plain rhetorical delivery of the words to which they were set; melodious or rhythmic phrases being everywhere carefully avoided, as not only unnecessary, but absolutely detrimental to the desired effect so detrimental, that the difficulty of adapting good Recitative to Poetry written in short rhymed verses is almost insuperable, the jingle of the metre tending to crystallise itself in regular form with a persistency which is rarely overcome except by the greatest Masters. Hence it is, that the best Poetry for Recitative is Blank Verse: and hence it is, that the same Intervals, the same Progressions, and the same Cadences, have been used over and over again, by Composers, who, in other matters, have scarcely a trait in common. We shall best illustrate this by selecting a few set forms from the inexhaustible store at our command, and shewing how these have been used by some of the greatest writers of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries: premising that, in phrases ending with two or more reiterated notes, it has been long the custom to sing the first as an Appoggiatura, a note higher than the rest. We have shewn this in three cases, but the rule applies to many others.

Typical Forms.

Examples of their occurrence.

The universal acceptance of these, and similar figures, by Composers of all ages, from Peri down to Wagner, sufficiently proves their fitness for the purpose for which they were originally designed. But, the staunch conservatism of Recitativo secco goes even farther than this. Its Accompaniment has never changed. The latest Composers who have employed it have trusted for its support, to the simple Basso continuo, which neither Peri, nor Carissimi, nor Handel, nor Mozart, care to reinforce by the introduction of a fuller Accompaniment. The only modification of the original idea which has found favour in modern times has been the substitution of Arpeggios, played by the principal Violoncello, for the Harmonies formerly filled in upon the Harpsichord, or Organ and we believe we are right in asserting that this device has never been extensively adopted in any other country than our own. Here it prevailed exclusively for many years. A return has however lately been made to the old method by the employment of the Piano, first by Mr. Otto Goldschmidt at a performance of Handel's L'Allegro in 1863, and more recently by Dr. Stainer, at St. Paul's, in various Oratorios.

Again, this simple kind of Recitative is as free, now, as it was in the first year of the 17th century, from the trammels imposed by the laws of Modulation. It is the only kind of Music which need not begin and end in the same Key. As a matter of fact, it usually begins upon some Chord not far removed from the Tonic Harmony of the Aria, or Concerted Piece, which preceded it; and ends in, or near, the Key of that which is to follow: but its intermediate course is governed by no law whatever beyond that of euphony. Its Harmonies exhibit more variety, now, than they did two centuries ago; but they are none the less free to wander wherever they please, passing through one Key after another, until they land the hearer somewhere in the immediate neighbourhood of the Key chosen for the next regularly-constructed Movement. Hence it is, that Recitatives of this kind are always written without the introduction of Sharps, or Flats, at the Signature; since it is manifestly more convenient to employ any number of Accidentals that may be needed, than to place three or four Sharps at the beginning of a piece which is perfectly at liberty to end in seven Flats.

But, notwithstanding the unchangeable character of Recitative secco, declamatory Music has not been relieved from the condition which imposes progress upon every really living branch of Art. As the resources of the Orchestra increased, it became evident that they might be no less profitably employed, in the Accompaniment of highly impassioned Recitative, than in that of the Aria, or Chorus: and thus arose a new style of Rhetorical Composition, called Accompanied Recitative (Recitative stromentato), in which the vocal phrases, themselves unchanged, received a vast accession of power, by means of elaborate Orchestral Symphonies interpolated between them, or even by instrumental passages designed expressly for their support. The invention of this new form of impassioned Monologue is generally ascribed to Alessandro Scarlatti (1659–1725), who used it with admirable effect, both in his Operas and his Cantatas; but its advantages, in telling situations, were so obvious, that it was immediately adopted by other Composers, and at once recognised as a legitimate form of Art—not, indeed, as a substitute for Simple Recitative, which has always been retained for the ordinary business of the Stage, but, as a means of producing powerful effects, in Scenes, or portions of Scenes, in which the introduction of the measured Aria would be out of place. [App. p.767 "for correction [of this sentence] see vol. iii. p. 695, note 2."]

It will be readily understood, that the stability of Simple Recitative was not communicable to the newer style. The steadily increasing weight of the Orchestra, accompanied by a correspondent increase of attention to Orchestral Effects, exercised an irresistible influence over it. Moreover, time has proved it to be no less sensitive to changes of School, and Style, than the Aria itself; whence it frequently happens that a Composer may be as easily recognised by his Accompanied Recitatives as by his regularly constructed Movements. Scarlatti's Accompaniments exhibit a freedom of thought immeasurably in advance of the age in which he lived. Sebastian Bach's Recitatives, though priceless, as Music, are more remarkable for the beauty of their Harmonies, than for that spontaneity of expression which is rarely attained by Composers unfamiliar with the traditions of the Stage. Handel's, on the contrary, though generally based upon the simplest possible harmonic foundation, exhibit a rhetorical perfection of which the most accomplished Orator might well feel proud: and we cannot doubt that it is to this high quality, combined with a never-failing truthfulness of feeling, that so many of them owe their deathless reputation to the unfair exclusion of many others, of equal worth, which still lie hidden among the unclaimed treasures of his long-forgotten Operas. Scarcely less successful, in his own peculiar style, was Haydn, whose 'Creation' and 'Seasons,' owe half their charm to their pictorial Recitatives. Mozart was so uniformly great, in his declamatory passages, that it is almost impossible to decide upon their comparative merits; though he has certainly never exceeded the perfection of 'Die Weiselehre dieser Knaben,' or 'Non temer.' Beethoven attained his highest flights in 'Abscheulicher! wo eilst du hin?' and 'Ah, perfido!' Spohr, in 'Faust,' and 'Die letzten Dinge.' Weber, in 'Der Freischütz.' The works of Cimarosa, Rossini, and Cherubini, abound in examples of Accompanied Recitative, which rival their Airs in beauty: and it would be difficult to point out any really great Composer who has failed to appreciate the value of Scarlatti's happy invention.

Yet, even this invention failed, either to meet the needs of the Dramatic Composer, or to exhaust his ingenuity. It was reserved for Gluck to strike out yet another form of Recitative, destined to furnish a more powerful engine for the production of a certain class of effects than any that had preceded it. He it was, who first conceived the idea of rendering the Orchestra, and the Singer, to all outward appearance, entirely independent of each other: of filling the Scene, so to speak, with a finished orchestral groundwork, complete in itself, and needing no vocal Melody to enhance its interest, while the Singer declaimed his part in tones, which, however artfully combined with the Instrumental Harmony, appeared to have no connection with it whatever; the resulting effect resembling that which would be produced, if, during the interpretation of a Symphony, some accomplished Singer were to soliloquise, aloud, in broken sentences, in such wise as neither to take an ostensible share in the performance, nor to disturb it by the introduction of irrelevant discord. An early instance of this may be found in 'Orfeo.' After the disappearance of Euridice, the Orchestra plays an excited Crescendo, quite complete in itself, during the course of which Orfeo distractedly calls his lost Bride, by name, in tones which harmonise with the Symphony, yet have not the least appearance of belonging to it. In 'Iphigénie en Tauride,' and all the later Operas, the same device is constantly adopted; and modern Composers have also used it, freely—notably Spohr, who opens his 'Faust' with a Scene, in which a Band behind the stage plays the most delightful of Minuets, while Faust and Mephistopheles sing an ordinary Recitative, accompanied by the usual Chords played by the regular Orchestra in front.

By a process of natural, if not inevitable development, this new style led to another, in which the Recitative, though still distinct from the Accompaniment, assumed a more measured tone, less melodious than that of the Air, yet more so, by far, than that used for ordinary declamation. Gluck has used this peculiar kind of Mezzo Recitativo with indescribable power, in the Prison Scene, in 'Iphigénie en Tauride.' Spohr employs it freely, almost to the exclusion of symmetrical Melody, in 'Die letzten Dinge.' Wagner makes it his cheval de bataille, introducing it everywhere, and using it, as an ever-ready medium, for the production of some of his most powerful Dramatic Effects. We have already discussed his theories on this subject, so fully, that it is unnecessary to revert to them here. [See Opera, vol. ii. pp. 526–539.] Suffice it to say that his Melos, though generally possessing all the more prominent characteristics of pure Recitative, sometimes approaches so nearly to the rhythmic symmetry of the Song, that—as in the case of 'Nun sei bedankt, mein lieben Schwann!'—it is difficult to say, positively, to which class it belongs. We may, therefore, fairly accept this as the last link in the chain which fills up the long gap between simple 'Recitative secco,' and the finished Aria.[ W. S. R. ]