A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Rhythm

RHYTHM. This much-used and many-sided term may be defined as 'the systematic grouping of notes with regard to duration.' It is often inaccurately employed as a synonym for its two sub-divisions, Accent and Time, and in its proper signification bears the same relation to these that metre bears to quantity in poetry.

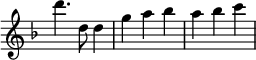

The confusion which has arisen in the employment of these terms is unfortunate, though ao frequent that it would appear to be natural, and therefore almost inevitable. Take a number of notes of equal length, and give an emphasis to every second, third, or fourth, the music will be said to be in 'rhythm' of two, three, or four—meaning in time. Now take a number of these groups or bars and emphasize them in the same way as their sub-divisions: the same term will still be employed, and rightly so. Again, instead of notes of equal length, let each group consist of unequal notes, but similarly arranged, as in the following example from Schumann—

![\relative d { \clef bass \time 2/4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \partial 8 \key d \major

<d fis a>8 | q8.[ <fis a d>16 <a d fis>8] <d fis a> |

q8.[ <a d fis>16 <fis a d>8] q |

<g b e>8.[ <fis b fis'>16 <e b' g'>8] <cis a' e' a> |

<b a' d fis>8.[ <fis' a d>16 <a cis e>8] }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/a/q/aquyfme9jgfbe9vc4dvv01g9ivns20i/aquyfme9.png)

or in the Vivace of Beethoven's No. 7 Symphony: the form of these groups also is spoken of as the 'prevailing rhythm,' though here accent is the only correct expression.

Thus we see that the proper distinction of the three terms is as follows:—

Accent arranges a heterogeneous mass of notes into long and short;

Time divides them into groups of equal duration;

Rhythm does for these groups what Accent does for notes.

In short, Rhythm is the Metre of Music.

This parallel will help us to understand why the uneducated can only write and fully comprehend music in complete sections of four and eight bars.

Rhythm, considered as the orderly arrangement of groups of accents—whether bars or parts of bars—naturally came into existence only after the invention of time and the bar-line. Barbarous music, though more attentive to accent than melody, plain-chant and the polyphonic church music of the 16th century, fugues and most music in polyphonic and fugal style, all these present no trace of rhythm as above defined. In barbarous music and plain-chant this is because the notes exist only with reference to the words, which are chiefly metre-less: in polyphonic music it is because the termination of one musical phrase (foot, or group of accents) is always coincident with and hidden by the commencement of another. And this although the subject may consist of several phrases and be quite rhythmical in itself, as is the case in Bach's Organ Fugues in G minor and A minor. The Rhythmus of the ancients was simply the accent prescribed by the long and short syllables of the poetry, or words to which the music was set, and had no other variety than that afforded by their metrical laws. Modern music, on the other hand, would be meaningless and chaotic—a melody would cease to be a melody—could we not plainly perceive a proportion in the length of the phrases.

The bar-line is the most obvious, but by no means a perfect, means of distinguishing and determining the rhythm; but up to the time of Mozart and Haydn the system of barring was but imperfectly understood. Many even of Handel's slow movements have only half their proper number of bar-lines, and consequently terminate in the middle of a bar instead of at the commencement; as for instance, 'He shall feed His flock' (which is really in 6–8 time), and 'Surely He hath borne our griefs' (which should be 4–8 instead of ![]() ). Where the accent of a piece is strictly binary throughout, composers, even to this day, appear to be often in doubt about the rhythm, time, and barring of their music. The simple and unmistakable rule for the latter is this: the last strong accent will occur on the first of a bar, and you have only to reckon backwards. If the piece falls naturally into groups of four accents it is four in a bar, but if there is an odd two anywhere it should all be barred as two in a bar. Ignorance or inattention to this causes us now and then to come upon a sudden change from

). Where the accent of a piece is strictly binary throughout, composers, even to this day, appear to be often in doubt about the rhythm, time, and barring of their music. The simple and unmistakable rule for the latter is this: the last strong accent will occur on the first of a bar, and you have only to reckon backwards. If the piece falls naturally into groups of four accents it is four in a bar, but if there is an odd two anywhere it should all be barred as two in a bar. Ignorance or inattention to this causes us now and then to come upon a sudden change from ![]() to 2–4 in modern music.

to 2–4 in modern music.

With regard to the regular sequence of bars with reference to close and cadence—which is the true sense of rhythm—much depends upon the character of the music. The dance-music of modern society must necessarily be in regular periods of 4, 8, or 16 bars. Waltzes, though written in 3–4 time, are almost always really in 6–8, and a dance-music writer will sometimes, from ignorance, omit an unaccented bar (really a half-bar), to the destruction of the rhythm. The dancers, marking the time with their feet, and feeling the rhythm in the movement of their bodies, then complain, without understanding what is wrong, that such a waltz is 'not good to dance to.'

In pure music it is different. Great as are the varieties afforded by the diverse positions and combinations of strong and weak accents, the equal length of bars, and consequently of musical phrases, would cause monotony were it not that we are allowed to combine sets of two, three, and four bars. Not so freely as we may combine the different forms of accent, for the longer divisions are less clearly perceptible; indeed the modern complexity of rhythm, especially in German music, is one of the chief obstacles to its ready appreciation. Every one, as we have already said, can understand a song or piece where a half-close occurs at each fourth and a whole close at each eighth bar, where it is expected; but when an uneducated ear is continually being disappointed and surprised by unexpected prolongations and alterations of rhythm, it soon grows confused and unable to follow the sense of the music. Quick music naturally allows—indeed demands—more variety of rhythm than slow, and we can scarcely turn to any Scherzo or Finale of the great composers where such varieties are not made use of. Taking two-bar rhythm as the normal and simplest form—just as two notes form the simplest kind of accent—the first variety we have to notice is where one odd bar is thrust in to break the continuity, as thus in the Andante of Beethoven's C minor Symphony:

![\relative e' { \key aes \major \time 3/8 \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \partial 8

ees16. g32 | \mark "•" <aes ees c>8 q <bes g ees> |

<c aes>4 <aes ees c>16. <bes g ees>32 | \mark "•"

<c aes>8 q <des bes> | <ees c>4 ees16. f32 | \mark "•"

<< { <ges ees c>4 ees16. f32 | \mark "•" <ges ees c>4 ees16. f32 } \\

{ r8 a,4 | r8 a4 } >>

<aes c ees fis>4.:64 | \mark "•"

<g c e g>16.[ ees32] c8[ <d b g>] | c4 }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/u/nup1jrfrsz03ujmaz2ogn85vodv9dqi/nup1jrfr.png)

this may also be effected by causing a fresh phrase to begin with a strong accent on the weak bar with which the previous subject ended, thus really eliding a bar, as for instance in the minuet in Haydn's 'Reine de France' Symphony:

Here the bar marked (a) is the overlapping of two rhythmic periods.

Combinations of two-bar rhythm are the rhythms of four and six bars. The first of these requires no comment, being the most common of existing forms. Beethoven has specially marked in two cases (Scherzo of 9th Symphony, and Scherzo of C♯ minor Quartet) 'Ritmo de 4 battute,' because, these compositions being in such short bars, the rhythm is not readily perceptible. The six-bar rhythm is a most useful combination, as it may consist of four bars followed by two, two by four, three and three, or two, two and two. The well-known minuet by Lulli (from 'Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme') is in the first of these combinations throughout.

And the opening of the Andante of Beethoven's 1st Symphony is another good example. Haydn is especially fond of this rhythm, especially in the two first-named forms. Of the rhythm of thrice two bars a good specimen is afforded by the Scherzo of Schubert's C major Symphony, where, after the two subjects (both in four-bar rhythm) have been announced, the strings in unison mount and descend the scale in accompaniment to a portion of the first theme, thus:

A still better example is the first section of 'God save the Queen.'

This brings us to triple rhythm, uncombined with double.

Three-bar rhythm, if in a slow time, conveys a very uncomfortable lop-sided sensation to the uncultivated ear. The writer remembers an instance when the band could hardly be brought to play a section of an Andante in 9–8 time and rhythm of three bars. The combination of 3 x 3 x 3 was one which their sense of accent refused to acknowledge. Beethoven has taken the trouble in the Scherzo of his 9th Symphony to mark 'Ritmo di tre battute,' although in such quick time it is hardly necessary; the passage,

being understood as though written—

Numerous instances of triple rhythm occur, which he has not troubled to mark; as in the Trio of the C minor Symphony Scherzo:—

Rhythm of five bars is not, as a rule, productive of good effect, and cannot be used—any more than the other unusual rhythms—for long together. It is best when consisting of four bars followed by one, and is most often found in compound form—that is, as eight bars followed by two.

Minuet, Mozart's Symphony in C (No. 6).

A very quaint effect is produced by the unusual rhythm of seven. An impression is conveyed that the eighth bar—a weak one—has got left out through inaccurate sense of rhythm, as so often happens with street-singers and the like. Wagner has taken advantage of this in his 'Tanz der Lehrbuben' ('Die Meistersinger'), thus:—

It is obvious that all larger symmetrical groups than the above need be taken no heed of, as they are reducible to the smaller periods. One more point remains to be noticed, which, a beauty in older and simpler music, is becoming a source of weakness in modern times. This is the disguising or concealing of the rhythm by strong accents or change of harmony in weak bars. The last movement of Beethoven's Pianoforte Sonata in D minor (op. 31) affords a striking instance of this. At the very outset

we are led to think that the change of bass at the fourth bar, and again at the eighth, indicates a new rhythmic period, whereas the whole movement is in four-bar rhythm as unchanging as the semiquaver figure which pervades it. The device has the effect of preventing monotony in a movement constructed almost entirely on one single figure. The same thing occurs in the middle of the first movement of the Sonatina (op. 79, Presto alla Tedesca). Now in both of these cases the accent of the bars is so simple that the ear can afford to hunt for the rhythm and is pleased by the not too subtle artifice; but in slower and less obviously accented music such a device would be out of place: there the rhythm requires to be impressed on the hearer rather than concealed from him.

On analysing any piece of music it will be found that whether the ultimate distribution of the accents be binary or ternary, the larger divisions nearly always run in twos, the rhythms of three, four, or seven being merely occasionally used to break the monotony. This is only natural, for, as before remarked, the comprehensibility of music is in direct proportion to the simplicity of its rhythm, irregularity in this point giving a disturbed and emotional character to the piece, until, when all attention to rhythm is ignored, the music becomes incoherent and incomprehensible, though not of necessity disagreeable. In 'Tristan and Isolde' Wagner has endeavoured, with varying success, to produce a composition of great extent, from which rhythm in its larger signification shall be wholly absent. One consequence of this is that he has written the most tumultuously emotional opera extant;, but another is that the work is a mere chaos to the hearer until it is closely studied. Actual popularity and general appreciation for such music is out of all question for some generations to come.[ F. C. ]