A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Rondo

RONDO (Fr. Rondeau). A piece of music having one principal subject, to which a return is always made after the introduction of other matter, so as to give a symmetrical or rounded form to the whole.

From the simplicity and obviousness of this idea it will be readily understood that the Rondo-form was the earliest and most frequent definite mould for musical construction. For a full tracing of this point see Form [i. 541, 552]. In fact the First Movement and the Rondo are the two principal types of Form, modifications of the Rondo serving as the skeleton for nearly every piece or song now written. Dr. Marx ('Allgemeine Musiklehre') distinguishes five forms of Rondo, but his description is involved, and, in the absence of any acknowledged authority for these distinctions, scarcely justifiable.

Starting with a principal subject of definite form and length, the first idea naturally was to preserve this unchanged in key or form through the piece. Hence a decided melody of eight or sixteen bars was chosen, ending with a full close in the tonic. After a rambling excursion through several keys and with no particular object, the principal subject was regained and an agreeable sense of contrast attained. Later on there grew out of the free section a second subject in a related key, and still later a third, which allowed the second to be repeated in the tonic. This variety closely resembles the first-movement form, the third subject taking the place of the development of subjects, which is rare in a Rondo. The chief difference lies in the return to the first subject immediately after the second. which is the invariable characteristic of the Rondo. The first of these classes is the Rondo from Couperin to Haydn, the second and third that of Mozart and Beethoven. The fully developed Rondo-form of Beethoven and the modern composers may be thus tabulated:—

| 1st sub. | 2nd sub. (dominant). |

1st sub. | 3rd sub. | 1st sub. | 2nd sub. (tonic). |

Coda. |

In the case of a Rondo in a minor key, the second subject would naturally be in the relative major instead of in the dominant.

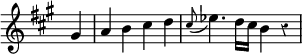

One example—perhaps the clearest as well as the best known in all music—will suffice to make this plan understood by the untechnical reader. Taking the Rondo of Beethoven's 'Sonata Pathetique' (op. 13) we find the first subject in C minor:—

this is of 17½ bars in length and ends with a full close in the key. Six bars follow, modulating into E♭, where we find the second subject, which is of unusual proportions compared with the first, consisting as it does of three separate themes:—

After this we return to the 1st subject, which ends just as before. A new start is then made with a third subject (or pair of subjects?) in A♭:—

this material is worked out for 24 bars and leads to a prolonged passage on a chord of the dominant seventh on G, which heightens the expectation of the return of the 1st subject by delaying it. On its third appearance it is not played quite to the end, but we are skilfully led away, the bass taking the theme, till, in the short space of four bars, we find the whole of the 2nd subject reappearing in C major. Then, as this is somewhat long, the 1st subject comes in again for the fourth time and a Coda formed from the 2nd section of the 2nd subject concludes the Rondo with still another 'positively last appearance' of No. 1.

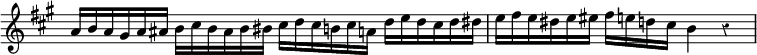

Beethoven's Rondos will all be found to present but slight modifications of the above form. Sometimes a 'working-out' or development of the 2nd subject will take the place of the 3rd subject, as in the Sonata in E (op. 90), but in every case the principal subject will be presented in its entirety at least three times. But as this was apt to lead to monotony—especially in the case of a long subject like that in the Sonata just quoted—Beethoven introduced the plan of varying the theme slightly on each repetition, or of breaking off in the middle. It is in such delicate and artistic modifications and improvements as these that the true genius shows itself, and not in the complete abandonment of old rules. In the earliest example we can take—the Rondo of the Sonata in A (op. 2, No. 2), the form of the opening arpeggio is altered on every recurrence, while the simple phrase of the third and fourth bars

is thus varied:—

In the Rondo of the Sonata in E♭ (op. 7) again, we find the main subject cut short on its second appearance, while on its final repetition all sorts of liberties are taken with it; it is played an octave higher than its normal place, a free variation is made on it, and at last we are startled by its being thrust into a distant key—E♮. This last effect has been boldly pilfered by many a composer since—Chopin in the Rondo of his E minor Pianoforte Concerto, for instance. It is needless to multiply examples: Beethoven shows in each successive work how this apparently stiff and rigid form can be invested with infinite variety and interest; he always contradicted the idea (in which too few have followed him) that a Rondo was bound in duty to be an 8-bar subject in 2-4 time, of one unvarying, jaunty, and exasperatingly jocose character. The Rondo of the E♭ Sonata is most touchingly melancholy, so is that to the Sonata in E (op. 90), not to mention many others. There will always remain a certain stiffness in this form, owing to the usual separation of the subject from its surroundings by a full close. When this is dispensed with, the piece is said to be in Rondo-form, but is not called a Rondo (e.g. the last movement of Beethoven's Sonata op. 2, No. 3).

[ F. C. ]