A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Solmisation

SOLMISATION (Lat. Solmisatio). The art of illustrating the construction of the Musical Scale by means of certain syllables, so associated with the sounds of which it is composed as to exemplify both their relative proportions, and the functions they discharge as individual members of a system based upon fixed mathematical principles.

The laws of Solmisation are of scarcely less venerable antiquity than those which govern the accepted proportions of the Scale itself. They first appear among the Greeks, and doubtless proved as useful to the Fathers of the Lyric Drama, and the Singers who took part in its gorgeous representations in the great Theatre at Athens, as they have since done to Vocalists of all ages. Making the necessary allowance for differences of Tonality, the guiding principle in those earlier times was precisely the principle by which we are guided now. Its essence consisted in the adaptation to the Tetrachord of such syllables as should ensure the recognition of the Hemitone, wherever it occurred. Now, the Hemitone of the Greeks, though not absolutely identical with our Diatonic Semitone, was its undoubted homologue;[1] and, throughout their system, this Hemitone occurred between the first and second sounds of every Tetrachord; just as, in our Major Scale, the Semitones occur between the third and fourth Degrees of the two disjunct Tetrachords by which the complete Octave is represented. Therefore, they ordained that the four sounds of the Tetrachord should be represented by the four syllables, τα, τε, τη, τω; and that, in passing from one Tetrachord to another, the position of these syllables should be so modified, as in every case to place the Hemitone between τα and τε, and the two following Tones between τε and τη, and τη and τω, respectively.[2]

When, early in the 11th century, Guido d'Arezzo substituted his Hexachords for the Tetrachords of the Greek system, he was so fully alive to the value of this principle, that he adapted it to another set of syllables, sufficiently extended to embrace six sounds instead of four. In the choice of these he was guided by a singular coincidence. Observing that the Melody of a Hymn, written about the year 770 by Paulus Diaconus, for the Festival of S. John the Baptist, was so constructed, that its successive phrases began with the six sounds of the Hexachord, taken in their regular order, he adopted the syllables sung to these notes as the basis of his new system of Solmisation, changing them from Hexachord to Hexachord, on principles to be hereafter described, exactly as the Greeks had formerly changed their four syllables from Tetrachord to Tetrachord.

It will be seen, from this example, that the syllables, Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La,[3] were originally sung to the notes C, D, E, F, G, A; that is to say, to the six sounds of the Natural Hexachord: and that the Semitone fell between the third and fourth syllables, Mi and Fa, and these only. [See Hexachord.] But, when applied to the Hard Hexachord, these same six syllables represented the notes G, A, B, C, D, E; while, in the Soft Hexachord, they were sung to F, G, A, B♭, C, D. The note C therefore was sometimes represented by Ut, sometimes by Fa, and sometimes by Sol, according to the Hexachord in which it occurred; and was consequently called, in general terms, C sol-fa-ut. In like manner, A was represented either by La, Mi, or Re; and was hence called A la-mi-re, as indicated, in our example, by the syllables printed above the Stave. But, under no possible circumstances could the Semitone occur between any other syllables than Mi and Fa; and herein, as we shall presently see, lay the true value of the system.

So long as the compass of the Melody under treatment did not exceed that of a single Hexachord, the application of this principle was simple enough; but, for the Solmisation of Melodies embracing a more extended range, it was found necessary to introduce certain changes, called Mutations, based upon a system corresponding exactly with the practice of the Greeks. [See Mutation.] Whenever a given Melody extended (or modulated) from one Hexachord into another, the syllables pertaining to the new series were substituted for those belonging to the old one, at some convenient point, and continued, in regular succession, until it became convenient to change them back again; by which means the compass of the Scale could be enlarged to any required extent.

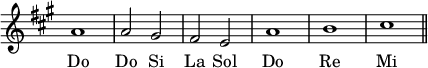

For instance, in the following example the passage begins at (a), in the Natural Hexachord of C, but extends upwards three notes beyond its compass, and borrows a B♭ from the Soft Hexachord of F. As it is not considered desirable to defer the change until the extreme limits of the first Hexachord have been reached, it may here be most conveniently made at the note G. Now, in the Natural Hexachord, G is represented by the syllable Sol; in the Soft Hexachord, by Re. In this case, therefore, we have only to substitute Re for Sol, at this point; and to continue the Solmisation proper to the Soft Hexachord to the end of the passage, taking no notice whatever of the syllable printed in Italics.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

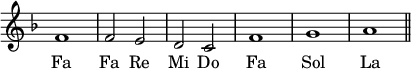

At (b), on the other hand, the passage extends downwards, from the Hexachord of G, into that of C. Here, the change may be most conveniently effected by substituting the La of the last-named Hexachord for the Re of the first, at the note A.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

The first of these Mutations is called Sol-re, in allusion to its peculiar interchange of syllables: the second is called Re-la. As a general rule, Re is found to be the most convenient syllable for ascending Mutations, and La, for those which extend downwards, in accordance with the recommendation contained in the following Distich:

Vocibus utaris solum mutando duabus

Per re quidem sursum mutatur, per la deorsum.

This rule, however, does not exclude the occasional use of the forms contained in the subjoined Table, though the direct change from the Hard to the Soft Hexachord, and vice versa, is not recommended.

| Descending Mutations. | ||

| 1. | Fa-sol. | From the Hard to the Soft Hexachord, changing on C. |

| 2. | Mi-la. | Nat. to Hard Hex. changing on E. Soft to Nat. Hex. changing on A. |

| 3. | Re-la. | Hard to Nat. Hex. changing on A. Nat. to Soft Hex changing on D. |

| 4. | Re-mi. | Hard to Soft Hex. changing on A. |

| 5. | Re-sol. | Nat. to Hard Hex. changing on D. Soft to Nat. Hex. changing on G. |

| 6. | Sol-la. | Hard to Soft Hex. changing on D. |

| 7. | Ut-fa. | Nat. to Hard Hex. changing on C. Soft to Nat. Hex. changing on F. |

| 8. | Ut-re. | Hard to Soft Hex. changing on G. |

| Ascending Mutations. | ||

| 9. | Fa-ut. | Hard to Nat. Hexachord, changing on C. Nat. to Soft Hex. changing on F. |

| 10. | La-mi. | Hard to Nat. Hex. changing on E. |

| 11. | La-re. | Nat. to Hard Hex. changing on A. Soft to Nat. Hex. changing on D. |

| 12. | La-sol. | Soft to Hard Hex. changing on D. |

| 13. | Mi-re. | Do.Do.A. |

| 14. | Re-ut. | Do.Do.G. |

| 15. | Sol-fa. | Do.Do.C. |

| 16. | Sol-re. | Hard to Nat. Hex. changing on D. Nat to Soft Hex. changing on G. |

| 17. | Sol-ut. | Nat. to Hard Hex. changing on G. Soft to Nat. Hex. changing on C. |

The principle upon which this antient system was based is that of 'the Moveable Ut'—or, as we should now call it, 'the Moveable Do'; an arrangement which assists the learner very materially, by the recognition of a governing syllable, which, changing with the key, regulates the position of every other syllable in the series, calls attention to the relative proportions existing between the root of the Scale and its attendant sounds, and, in pointing out the peculiar characteristics of each subordinate member of the system, lays emphatic stress upon its connection with its fellow degrees, and thus teaches the ear, as well as the understanding. We shall presently have occasion to consider the actual value oi these manifold advantages; but must first trace their historical connection with the Solmisation of a later age.

So long as the Ecclesiastical Modes continued in use, Guido's system answered its purpose so thoroughly, that any attempt to improve upon it would certainly have ended in failure. But, when the functions of the Leading-Note were brought more prominently into notice, the demand for a change became daily more and more urgent. The completion of the Octave rendered it not only desirable, but imperatively necessary, that the sounds should no longer be arranged in Hexachords, but, in Heptachords, or Septenaries, for which purpose an extended sylabic arrangement was needed. We have been unable to trace back the definite use of a seventh syllable to an earlier date than the year 1599, when the subject was broached by Erich van der Putten (Erycius Puteanus) of Dordrecht, who, at pages 54, 55 of his 'Pallas modulata,'[4] proposed the use of BI, deriving the idea from the second syllable of labii.' No long time, however, elapsed, before an overwhelming majority of theorists decided upon the adoption of SI, the two letters of which were suggested by the initials of 'Sancte Ioannes'—the Adonic verse which follows the three Sapphics in the Hymn already quoted.[5] The use of this syllable was strongly advocated by Sethus Calvisius, in his 'Exercitatio musicæ tertia,' printed in 1611. Since then, various attempts have been made to supplant it, in favour of Sa, Za, Ci, Be, Te, and other open syllables;[6] but, the suggested changes have rarely survived their originators, though another one, of little less importance the substitution of Do for Ut on account of its greater resonance—has, for more than two hundred years, been almost universally accepted. [See ../Do/]].] Lorenzo Penna,[7] writing in 1672, speaks of Do as then in general use in Italy; and Gerolamo Cantone[8] alludes to it, in nearly similar terms, in 1678, since which period the use of Ut has been discontinued, not only in Italy, but in every country in Europe, except France.

In Germany and the Netherlands far more sweeping changes than these have been proposed, from time to time, and even temporarily accepted. Huberto Waelrant (1517–1595), one of the brightest geniuses of the Fourth Flemish School, introduced, at Antwerp, a system called 'Bocedisation,' or 'Bobisation,' founded on seven syllables—Bo, Ce, Di, Ga, Lo, Ma, Ni—which have since been called the 'Voces Belgicæ.' At Stuttgart, Daniel Hitzler (1576–1635) based a system of 'Bebisation' upon La, Be, Ce, De, Me, Fe, Ge. A century later, Graun (1701–1759) invented a method of 'Damenisation,' founded upon the particles, Da, Me, Ni, Po, Tu, La, Be. But none of these methods have survived.

In England, the use of the syllables Ut and Re died out completely before the middle of the 17th century; and recurring changes of Mi, Fa, Sol, La, were used, alone, for the Solmisation of all kinds of Melodies. Butler mentions this method as being in general use, in 1636[9]; and Playford calls attention to the same fact in 1655.[10]

In France, the original syllables, with the added Si, took firmer root than ever in Italy; for it had long been the custom, in the Neapolitan Schools, to use the series beginning with Do for those Keys only in which the Third is Major. For Minor Keys, the Neapolitans begin with Re; using Fa for an accidental Flat, and Mi for a Sharp. Durante, however, when his pupils were puzzled with a difficult Mutation, used to cry out, 'Only sing the syllables in tune, and you may name them after devils, if you like.'

The truth is, that, as long as the syllables are open, their selection is a matter of very slight importance. They were never intended to be used for the formation of the Voice, which may be much better trained upon the sound of the vowel, A, as pronounced in Italian, than upon any other syllable whatever. Their use is, to familiarise the Student with the powers and special peculiarities of the sounds which form the Scale: and here it is that the arguments of those who insist upon the use of a 'fixed,' or a 'moveable Do,' demand our most careful consideration. The fact that in Italy and France the syllables Ut (Do), Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Si, are always applied to the same series of notes, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and used as we ourselves use the letters, exercises no effect whatever upon the question at issue. It is quite possible for an Italian, or a Frenchman, to apply the 'fixed Do system' to his method of nomenclature, and to use the 'moveable Do' for purposes of Solmisation. The writer himself, when a child, was taught both systems simultaneously, by his first instructor, John Purkis, who maintained, with perfect truth, that each had its own merits, and each its own faults. In matters relating to absolute pitch, the fixed Do is all that can be desired. The 'moveable Do' ignores the question of pitch entirely; but it calls the Student's attention to the peculiar functions attached to the several Degrees of the Scale so clearly, that, in a very short time, he learns to distinguish the Dominant, the Sub-Mediant, the Leading-Note, or any other Interval of any given Key, without the possibility of mistake, and that, by simply sol-faing the passage in the usual manner.

The following example shows the first phrase of the 'Old Hundredth Psalm,' transposed into different Keys, with the Solmisation proper to both the fixed and the moveable Do.

(a) Moveable Do.

(b) Moveable Do.

(c) Moveable Do.

(d) Fixed Do.

(e) Fixed Do.

This example has been so arranged as to bring into prominent notice one of the strongest objections that has ever been brought against the use of the fixed Do. The system makes no provision for the indication of Flats or Sharps. Sol represents G♮ in the last division of our example, and G♯ in the last but one. In a tract published at Venice, in 1746,[11] an anonymous member of the Roman Academy called 'Arcadia,' proposed to remove the difficulty, by adding to the seven recognised syllables five others, designed to represent the Sharps and Flats most frequently used; viz. Pa (C♯, D♭), Bo (D♯, E♭), Tu (F♯, G♭), De (G♯, A♭), No (A♯, B♭). This method was adopted by Hasse, and highly approved by Giambattista Mancini: but, in 1768, a certain Signor Serra endeavoured to supersede it by a still more numerous collection of syllables; using Ca, Da, Ae, Fa, Ga, A, Ba, to represent the seven natural notes, A, B, C, D, E, F, G; Ce, De, E, Fe, Ge, Ao, Be, to represent the same notes, raised by a series of Sharps; and Ci, Di, Oe, Fi, Gi, Au, Bi, to represent them, when lowered by Flats.

[ W. S. R. ]

- ↑ The Diatonic Semitone is represented by the fraction 1516; the Greek Hemitone by 248⁄256, that is to say, by a Perfect Fourth, minus two Greater Tones.

- ↑ Though the true Pronunciation of the Greek vowels is lost, we are eft without the means of forming an approximate idea of it, since Homer uses the syllable βὴ, to imitate the bleating of the sheep.

- ↑ Gerard Vossius, in his tract 'De quatuor Artibus popularibus' (Amsterdam 1650), mentions the following Distich as having been written, shortly after the time of Guido, for the purpose of impressing the six syllables upon the learner's memory—

'Cur adhibes tristi numeros cantumque labori?

UT RElevet MIserum FAtum SOLitosque LAbores.' - ↑ 'Pallas modulata, sive Septem discrimina vocum' (Milan, 1599), afterwards reprinted, under the title of 'Musathena' (Hanover, 1602).

- ↑ It has been said, that, in certain versions of the Melody, the first syllable of the Adonic verse is actually sung to the note B; but we have never met with such a version, and do not believe in the possibility of its existence.

- ↑ See Si. vol. iii. p. 490.

- ↑ 'Albori musicale' (Bologna, 1672).

- ↑ 'Armonia Gregoriana' (Turin, 1678).

- ↑ 'Principles of Musick,' by C. Butler (Lond. 1636).

- ↑ 'Introduction to the Skill of Musick' (Lond. 1655).

- ↑ Riflessioni sopra alla maggior facilità che trovasi nel apprendere il canto, etc., etc. (Venezia, 1746.)