A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Tablature

TABLATURE (Lat. Tabulatura, from Tabula, a table, or flat surface, prepared for writing; Ital. Intavolatura; Fr. Tablature; Germ. Tabulatur). A method of Notation, chiefly used, in the 15th and 16th centuries, for the Lute, though occasionally employed by Violists, and Composers for some other Instruments of like character.

In common with all other true systems of Notation, Tablature traces its descent in a direct line from the Gamut of Guido, though, in its later forms, it abandons the use of the Stave. It was used, in the 16th century, by Organists, as a means of indicating the extended Scale of the instruments, which, especially in Germany, were daily increasing in size and compass. For this purpose the lower Octave of the Gamut was described in capital letters; the second, in small letters; the third, in small letters with a line drawn above them:—

This Scale was soon very much extended; the notes below Gamut G (Γ) being distinguished by double capitals, and those above g̅ by small letters with two lines above them, the lower notes being described as belonging to the Double Octave, and the two upper Octaves as the Once-marked, and Twice-marked Octaves.

Several minor differences occur in the works of early authors. Agricola, for instance, in his 'Musica instrumentalis,' carries the Scale down to FF; and, instead of capitals, permits the use of small letters with lines below them for the lower Octaves—ff g a etc. But the principle remained unchanged; and when the C Scale was universally adopted for the Organ, its Tablature assumed the form which it retains in Germany to the present day:—

The comparatively recent adoption of the C Pedal-board in England has led to some confusion as to the Tablature of the lower Octave; and hence our English organ-builders usually describe the Great C as Double C, using tripled capitals for the lowest notes—a circumstance which renders caution necessary in comparing English and German specifications, where the actual length of the pipes is not marked.

In process of time, a hook was added to the letters, for the purpose of indicating a ♯; as, c̨ (c♯), d̨ (d♯), etc.: and, in the absence of a corresponding sign for the ♭, ꞔ was written for d♭, ᶁ for e♭, etc., giving rise, in the Scale of E♭, to the monstrous progression, D♯, F, G, G♯, A♯, C, D, D♯—an anomaly which continued in common use, long after Michael Prætorius had recommended, in his 'Syntagma Musicum,'[1] the use of hooks below or above the letters, to indicate the two forms of Semitone—ꞔ, c᷎, etc. Even as late as 1808 the error was revived in connection with Beethoven's Eroica Symphony, which was announced in Vienna as 'Symphonie in Dis' (D♯).[2]

For indicating the length of the notes, the following forms were adopted, at a very early period:—

By means of these Signs, it was quite possible to express passages of considerable complexity, without the use of a Stave; though, very frequently, the two methods of Notation were combined, especially in Compositions intended for a Solo Voice, with Instrumental Accompaniment. For instance, in the following example from Arnold Schlick's 'Tabulaturen Etlicher lobgeseng und liedlein uff die orgeln und lauten' (Mentz, 1512), the melody is given on the Stave, and the Bass in Organ Tablature, the notes in the latter being twice as long as those in the former—a peculiarity by no means rare, in a method of Notation into which almost every writer of eminence introduced some novelty of his own devising.

Though no doubt deriving its origin from this early form, the method of Tablature used by Lutenists differed from it altogether in principle, being founded, in all its most important points, upon the peculiar construction of the instrument for which it was intended. [See Lute.] To the uninitiated, Music written on this system appears to be noted, either in Arabic numerals, or small letters, on an unusually broad Six-lined Stave. The resemblance to a Stave is, however, merely imaginary. The Lines really represent the six principal Strings of the Lute; while the letters, or numerals, denote the Frets by which the Strings are stopped, without indicating either the names of the notes to be sounded, or their relation to a fixed Clef. And, since the pitch of the notes produced by the use of the Frets will naturally depend upon that of the Open Strings, it is clearly impossible to decypher any given system of Tablature, without first ascertaining the method of tuning to which it is adapted, though the same principle underlies all known modifications of the general rule. We shall do well, therefore, to begin by comparing a few of the methods of tuning most commonly used on the Continent. [See Scordatura.]

Adrien le Roy, in his 'Briefve et facile Instruction pour aprendre la Tablature,' first printed at Paris in 1551, tunes the Chanterelle—i.e. the 1st, or highest String, to c̿, and the lower Strings, in descending order, to g̅, d̅, b♭, f, and c; see (a) in the following example. Vincenzo Galilei, in the Dialogue called 'Il Fronimo' (Venice, 1583), tunes his instrument thus, beginning with the lowest String, G, c, f, a, d̅, g̅, as at (b): and this system was imitated by Agricola, in his 'Musica Instrumentalis' (Wittenberg, 1529); and employed by John Dowland in his 'Bookes of Songes or Ayres' (London, 1597–1603), and by most English Lutenists, who, however, always reckoned downwards, from the highest sound to the lowest, as at (c). Thomas Mace describes the English method, in 'Musick's Monument' (London, 1676 fol.), chap. ix. Scipione Cerreto, 'Della prattica musica vocale et strumentale' (Napoli, 1601), gives a somewhat similar system, with 8 strings, tuned thus, beginning with the lowest, C, D, G, c, f, a, d̅, g̅, as at (d) in the example. Sebastian Virdung, in 'Musica getuscht' (1511), gives the following, reckoning upwards, as at (e)—A, d, g, b, e̅, a̅; and this method, which was once very common in Italy, is followed in a scarce collection of Songs with Lute Accompaniment, published at Venice by Ottaviano Petrucci, in 1509.

Adrien le Roy.

V. Galilei.

J. Dowland.

S. Cerreto.

O. Petrucci. Seb. Virdung.

It will be understood that these systems apply only to the six principal Strings of the Lute, which, alone, were governed by the Frets. The longer Strings, sympathetically tuned in pairs, by means of a separate neck, were entirely ignored, in nearly all systems of Tablature, and used only after the manner of a Drone, when they happened to coincide with the Tonic of the Key in which the Music was written. Of this nature are the two lowest Strings at (d) in the foregoing example.

Of the Lines—generally six in number—used to represent the principal Strings, Italian Lutenists almost always employed the lowest for the Chanterelle and the highest, for the gravest String. In France, England, Flanders, and Spain, the highest line was used for the Chanterelle, and the whole system reversed. The French system, however, was afterwards universally adopted, both in Italy and Germany—a circumstance which must be carefully borne in mind with regard to Music printed in those countries in the 17th century.

The Frets by which the six principal Strings were shortened, were represented, in Italy, by the numerals 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, to which were afterwards added the numbers 10, 11, 12, written x, ẋ, ẍ. In France and England the place of these numerals was supplied by the letters a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, etc.: and, after a time, these letters came into general use on the Continent also. Of course, one plan was just as good as the other; but there was this important practical difference between them: in England and France a represented the Open String, and b the first Fret; in Italy, the Open String was represented by a cypher, and the first Fret by the number 1. The letter b, therefore, corresponded to the figure 1; and c to 2. The letters, or numerals, were written either on the lines or in the spaces between them, each letter or numeral representing a Semitone in correspondence with the action of the Frets. Thus, when the lowest String was tuned to G, the actual note G was represented by a (or o); G♯, or A♭, by b (or 1); A, by c (or 2); A♯, or B♭, by d (or 3). But when the lowest String was tuned to A, b (or 1) represented B♭; c (or 2) represented B♮; and d (or 3) represented c. The following example shows both the French and the Italian Methods, the letters being written in the spaces—the usual plan in England—and the lowest place being reserved for an additional Open Bass String.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

French and English Tablature. J. Dowland.

Solution.

Italian Tablature.

V. Galilei.

Solution.

In order to indicate the duration of the notes, the Semibreve, Minim, Crotchet, Quaver, and Dot—or Point of Augmentation—were represented by the following signs, written over the highest line; each sign remaining in force until it was contradicted by another—at least, during the continuance of the bar. At the beginning of a new bar, the sign was usually repeated.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Semibreve. Minim. Crotchet. Quaver. Dot.

In order to afford the reader an opportunity of practically testing the rules, we give a few short examples selected from the works already mentioned; showing, in each case, the method of tuning employed—an indulgence very unusual in the old Lute-Books. Ordinary notation was of course used for the voice part.

J. Dowland.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Awake, sweet love, thou art re -- turned.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Italian method. Ottaviano Petrucci.

Af - flit - ti spir-ti miei

Solution.

These examples will enable the student to solve any ordinary forms of Tablature. Those who wish to study the supplementary Positions of Galilei, and the complicated methods of Gerle,[4] Besardus,[5] and other German writers, will find no difficulty in understanding the rules laid down in their respective treatises, after having once mastered the general features of this system.

It remains only to speak of Tablature as applied to other intruments than that for which it was originally designed.

During the reign of King James I, Coperario, then resident in England, adapted the Lute Tablature to Music written for the Bass Viol. This method of Notation was used for beginners only, and not for playing in concert. John Playford, in his 'Introduction to the Skill of Music' (10th edit., London, 1683), describes this method of Notation as the 'Lyra-way'; and calls the instrument the Lero, or Lyra-Viol. The six strings of the Bass Viol are tuned thus, beginning with the 6th, or lowest String, and reckoning upwards—D, G (Γ), c, e, a, d̄; and the method proposed is exactly the same as that used for the Lute, adapted to this system of tuning. Thus, on the 6th String, a denotes D (the Open String); b denotes D♯; c denotes E; etc. A player, therefore, who can read Lute-Music, will find no difficulty in reading this.

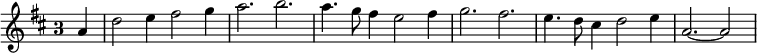

John Playford, enlarging upon Coperario's idea, recommended the same method for beginners on the Violin, adapting it to the four Open Strings of that instrument—G, D, A, E. The following Air, arranged on this system, for the Violin, is taken from a tune called 'Parthenia.'

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Parthenia.

Solution.

[ W. S. R. ]