A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Time, Beating

TIME, BEATING. Apart from what we know of the manners and customs of Greek Musicians, the practice of beating Time, as we beat it at the present day, is proved, by the traditions of the Sistine Choir, to be at least as old as the 15th century, if not very much older. In fact, the continual variations of Tempo which form so important an element in the interpretation of the works of Palestrina and other mediæval Masters, must have rendered the 'Solfa'—or, as we now call it, the Bâton—of a Conductor indispensable; and in the Pontifical Chapel it has been considered so from time immemorial. When the Music of the Polyphonic School gave place to Choruses accompanied by a full Orchestra, or, at least, a Thoroughbass, a more uniform Tempo became not only a desideratum, but almost a necessity. And because good Musicians found no difficulty in keeping together, in Movements played or sung at an uniform pace from beginning to end, the custom of beating time became less general; the Conductor usually exchanging his desk for a seat at the Harpsichord, whence he directed the general style of the performance, while the principal First Violin—afterwards called the Leader—regulated the length of necessary pauses, or the pace of ritardandi, etc., with his Violin-bow. Notwithstanding the evidence as to exceptional cases, afforded by Handel's Harpsichord, now in the South Kensington Museum,[1] we know that this custom was almost universal in the 18th century, and the earlier years of the 19th—certainly as late as the year 1829, when Mendelssohn conducted his Symphony in C Minor from the Pianoforte, at the Philharmonic Concert, then held at the Argyle Rooms.[2] But the increasing demand for effect and expression in Music rendered by the full Orchestra, soon afterwards led to a permanent revival of the good old plan, with which it would now be impossible to dispense.

Our present method of beating time is directly derived from that practised by the Greeks; though with one very important difference. The Greeks used an upward motion of the hand, which they called the ἄρσις (arsis), and a downward one, called θέσις (thesis). We use the same. The difference is, that with us the Thesis, or downbeat, indicates the accented part of the Measure, and the Arsis, or up-beat, its unaccented portion, while with the Greeks the custom was exactly the reverse. In the Middle Ages, as now, the Semibreve was considered as the norm from which the proportionate duration of all other notes was derived. This norm comprised two beats, a downward one and an upward one, each of which, of course, represented a Minim. The union of the Thesis and Arsis indicated by these two beats was held to constitute a Measure—called by Morley and other old English writers a 'Stroake.' This arrangement, however, was necessarily confined to Imperfect, or, as we now call it, Common Time. In Perfect, or Triple Time, the up-beats were omitted, and three down-beats only were used in each Measure; the same action being employed whether it contained three Semibreves or three Mimims.

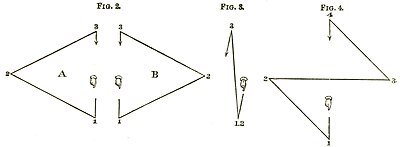

When two beats only are needed in the bar, we beat them, now, as they were beaten in the time of Morley; the down-beat representing the Thesis, or accented part of the Measure, and the up-beat, the Arsis, or unaccented portion, as at (A) in the annexed diagram.[3] But it sometimes happens that Prestissimo Movements are taken at a pace too rapid to admit the delivery of even two beats in a bar; and, in these cases, a single down-beat only is used, the upward motion of the Conductor's hand passing unnoticed, in consequence of its rapidity, as at (B).

When two beats only are needed in the bar, we beat them, now, as they were beaten in the time of Morley; the down-beat representing the Thesis, or accented part of the Measure, and the up-beat, the Arsis, or unaccented portion, as at (A) in the annexed diagram.[3] But it sometimes happens that Prestissimo Movements are taken at a pace too rapid to admit the delivery of even two beats in a bar; and, in these cases, a single down-beat only is used, the upward motion of the Conductor's hand passing unnoticed, in consequence of its rapidity, as at (B).

When three beats are needed in the bar, the custom is, in England, to beat once downwards, once to the left, and once upwards, as at (A) in Fig. 2. In France, the same system is used in the Concert-room; but in the Theatre it is usual to direct the second beat to the right, as at B, on the ground that the Conductor's Baton is thus rendered more easily visible to performers seated behind him. Both plans have their advantages and their disadvantages; but the fact that motions directed downwards, or towards the right, are always understood to indicate either primary or secondary accents, weighs strongly in favour of the English method.

But in very rapid Movements such as we find in some of Beethoven's Scherzos it is better to indicate 3-4 or 3-8 Time by a single downbeat, like those employed in very rapid 2-4; only that, in this case, the upward motion which the Conductor necessarily makes in preparation for the downward beat which is to follow must be made to correspond as nearly as possible with the third Crotchet or Quaver of the Measure, as in Fig. 3.

When four beats are needed in the bar, the first is directed downwards; the second towards the left; the third towards the right; and the fourth upwards. (Fig. 4.)

It is not possible to indicate more than four full beats in a bar, conveniently. But it is easy to indicate eight in a bar, by supplementing each full beat by a smaller one in the same direction, as at (A) in Fig. 5; or, by the same means, to beat six Quavers in a bar of very slow 3-4 Time, as at (B), or (C).

Compound Times, whether Common or Triple, may be beaten in two ways. In moderately quick Movements, they may be indicated by the same number of beats as the Simple Times from which they are derived: e.g. 6-8 Time may be beaten like 2-4; 6-4 like Alla Cappella; 12-8 like 4-4; 9-8 like 3-4; 9-16 like 3-8, etc., etc. But, in slower Movements, each constituent of the Compound Measure must be indicated by a triple motion of the Baton; that is to say, by one full beat, followed by two smaller ones, in the same direction; 6-4 or 6-8 being taken as at (A) in Fig. 6; 9-4 or 9-8 as at (B); and 12-8 as at (C). The advantage of this plan is, that in all cases the greater divisions of the bar are indicated by full beats, and the subordinate ones by half-beats.

For the anomalous rhythmic combinations with five or seven beats in the bar, it is difficult to lay down a law the authority of which is sufficiently obvious to ensure its general acceptation. Two very different methods have been recommended; and both have their strong and their weak points.

One plan is, to beat each bar of Quintuple

Time in two distinct sections; one containing two beats, and the other, three: leaving the question whether the duple section shall precede the triple one, or the reverse, to be decided by the nature of the Music. For Compositions like that by Brahms (Op. 21, No. 2), quoted in the preceding article, this method is not only excellent, but is manifestly in exact accordance with the author's intention—which, after all, by dividing each bar into two dissimilar members, the one duple and the other triple, involves a compromise quite inconsistent with the character of strict Quintuple Rhythm, notwithstanding the use that has been made of it in almost all other attempts of like character. The only Composition with which we are acquainted, wherein five independent beats in the bar have been honestly maintained throughout, without any compromise whatever, is Reeve's well-known 'Gypsies' Glee';[4] and, for this, the plan we have mentioned would be wholly unsuitable. So strictly impartial is the use of the five beats in this Movement, that it would be quite impossible to fix the position of a second Accent. The bar must therefore be expressed by five full beats; and the two most convenient ways of so expressing it are those indicated at (A) and (B) in Fig. 7.

This is undoubtedly the best way of indicating Quintuple Rhythm, in all cases in which the Composer himself has not divided the bar into two unequal members.

Seven beats in the bar are less easy to manage. In the first place, if a compromise be attempted, the bar may be divided in several different ways; e.g. it may be made to consist of one bar of 4-4, followed by one bar of 3-4; or, one bar of 3-4, followed by one bar of 4-4; or, one bar of 3-4, followed by two bars of 2-4; or, two bars of 2-4, followed by one of 3-4; or, one bar of 2-4, one of 3-4, and one of 2-4. But, in the absence of any indication of such a division by the Composer himself, it is much better to indicate seven honest beats in the bar. (Fig. 8.)

Yet another complication arises, in cases in which two or more species of Rhythm are employed simultaneously, as in the Minuet in 'Don Giovanni,' and the Serenade in Spohr's 'Weihe der Töne.' In all such cases, the safest rule is, to select the shortest Measure as the norm, and to indicate each bar of it by a single down-beat. Thus, in 'Don Giovanni,' the Minuet, in 3-4 Time, proceeds simultaneously with a Gavotte in 2-4, three bars of the latter being played against two bars of the former; and also with a Waltz in 3-8, three bars of which are played against each single bar of the Minuet, and two against each bar of the Gavotte. We must, therefore, select the Time of the Waltz as our norm; indicating each bar of it by a single down-beat; in which case each bar of the Minuet will be indicated by three down beats, each bar of the Gavotte by two, and each bar of the Waltz by one—an arrangement which no orchestral player can possibly misunderstand.

In like manner, Spohr's Symphony will be most easily made intelligible by the indication of a single down-beat for each Semiquaver of the part written in 9-16 Time—a method which Mendelssohn always adopted in conducting this Symphony.[5]

This method of using down-beats only is also of great value in passages which, by means of complicated syncopations, or other similar expedients, are made to go against the time; that is to say, are made to sound as if they were written in a different Time from that in which they really stand. But, in these cases, the downbeats must be employed with extreme caution, and only by very experienced Conductors, since nothing is easier than to throw a whole Orchestra out of gear, by means used with the best possible intention of simplifying its work. A passage near the conclusion of the Slow Movement of Beethoven's 'Pastoral Symphony' will occur to the reader as a case in point.

The rules we have given will ensure mechanical correctness in beating Time. But, the iron strictness of a Metronome, though admirable in its proper place, is very far from being the only qualification needed to form a good Conductor, who must not only know how to beat Time with precision, but must also learn to beat it easily and naturally, and with just so much action as may suffice to make the motion of his Bâton seen and understood by every member of the Orchestra, and no more. For the antics once practised by a school of Conductors, now happily almost extinct, were only so many fatal hindrances to an artistic performance.

Many Conductors beat Time with the whole arm, instead of from the wrist. This is a very bad habit, and almost always leads to a very much worse one—that of dancing the Bâton, instead of moving it steadily. Mendelssohn, one of the most accomplished Conductors on record, was very much opposed to this habit, and reprehended it strongly. His manner of beating was excessively strict; and imparted such extraordinary precision to the Orchestra, that, having brought a long level passage—such, for instance, as a continued forte—into steady swing, he was sometimes able to leave the performers, for a considerable time, to themselves; and would often lay down his Bâton upon the desk, and cease to beat Time for many bars together, listening intently to the performance, and only resuming his active functions when his instinct told him that his assistance would presently be needed. With a less experienced chief, such a proceeding would have been fatal: but, when he did it—and it was his constant practice—one always felt that everything was at its very best.

It may seem strange to claim, for the mechanical process of time-beating, the rank of an element—and a very important element—necessary to the attainment of ideal perfection in art: yet Mendelssohn's method of managing the Bâton proved it to be one. He held 'Tempo rubato' in abhorrence; yet he indicated nuances of emphasis and expression—as opposed to the inevitable Accents described in the foregoing article—with a precision which no educated musician ever failed to understand; and this with an effect so marked, that, when even Ferdinand David—a Conductor of no ordinary ability—took up the bâton after him at the Gewandhaus, as he frequently did, the soul of the Orchestra seemed to have departed.[6] The secret of this may be explained in a very few words. He knew how to beat strict Time with expression; and his gestures were so full of meaning, that he enabled, and compelled, the meanest Ripieno to assist in interpreting his reading. In other words, he united, in their fullest degree, the two qualifications which alone are indispensable in a great Conductor—the noble intention, and the power of compelling the Orchestra to express it. No doubt, the work of a great Conductor is immeasurably facilitated by his familiarity with the Orchestra he directs. Its members learn to understand and obey him, with a certainty which saves an immensity of labour. Sir Michael Costa, for instance, attained a position so eminent, that for very many years there was not, in all England, an orchestral player of any reputation who did not comprehend the meaning of the slightest motion of his hand. And hence it was that, during the course of his long career, he was able to modify and almost revolutionise the method of procedure to which he owed his earliest successes. Beginning with the comparatively small Orchestra of Her Majesty's Theatre, as it existed years ago, he gradually extended his sway, until he brought under command the vast body of 4000 performers assembled at the Handel Festivals at the Crystal Palace. As the number of performers increased, he found it necessary to invent new methods of beating Time for them; and, for a long period, used an uninterrupted succession of consecutive down-beats with a freedom which no previous Conductor had ever attempted. By using downbeats with one hand, simultaneously with the orthodox form in the other, he once succeeded, at the Crystal Palace, in keeping under command the two sides of a Double Chorus, when every one present capable of understanding the gravity of the situation believed an ignoble crash to be inevitable. And, at the Festival of 1883, his talented successor, Mr. Manns, succeeded, by nearly similar means, in maintaining order under circumstances of unexampled difficulty, caused by the sudden illness of the veteran chief whose place he was called upon to occupy without due time for preparation. In such cases as these the Conductor's left hand is an engine of almost unlimited power, and, even in ordinary conducting, it may be made extremely useful. It may beat four in a bar, or, in unequal combinations, even three, while the right hand beats two; or the reverse. For the purpose of emphasising the meaning of the right hand its action is invaluable. And it may be made the index of a hundred shades of delicate expression. Experienced players display a wonderful instinct for the interpretation of the slightest action on the part of an experienced Conductor. An intelligent wave of the baton will often ensure an effective sforzando, even if it be not marked in the copies. A succession of beats, beginning quietly, and gradually extending to the broadest sweeps the baton can execute, will ensure a powerful crescendo, and the opposite process, an equally effective diminuendo, unnoticed by the transcriber. Even a glance of the eye will enable a careless player to take up a point correctly, after he has accidentally lost his place—a very common incident, since too many players trust to each other for counting silent bars, and consequently re-enter with an indecision which energy on the part of the Conductor can alone correct.

It still remains to speak of one of the most important duties of a Conductor—that of starting his Orchestra. And here an old-fashioned scruple frequently causes great uncertainty. Many Conductors think it beneath their dignity to start with a preliminary beat: and many more players think themselves insulted when such a beat is given for their assistance. Yet the value of the expedient is so great, that it is madness to sacrifice it for the sake of idle prejudice. No doubt good Conductors and good Orchestras can start well enough without it, in all ordinary cases; but it is never safe to despise legitimate help, and never disgraceful to accept it. A very fine Orchestra, playing Beethoven's Symphony in C minor for the first time under a Conductor with whose 'reading' of the work they were unacquainted, would probably escape a vulgar crash at starting, even without a preliminary beat; but they would certainly play the first bar very badly: whereas, with such a beat to guide them, they would run no risk at all. For one preliminary beat suffices to indicate to a cultivated Musician the exact 'rate of speed at which the Conductor intends to take the Movement he is starting, and enables him to fulfil his chief's intention with absolute certainty.[ W. S. R. ]

- ↑ See vol. ii. p. 564, note.

- ↑ See vol. ii. p. 263.

- ↑ The diagrams indicate a downward motion towards 1, for the beginning of the bar. The hand then passes through the other beats, in the order in which they are numbered, and, on reaching the last, is supposed to descend thence perpendicularly, to 1, for the beginning of the next bar.

- ↑ See vol. iii. p. 61b.

- ↑ See the examples of these two passages, in the foregoing article (p. 121).

- ↑ We do not make this assertion on our own unsupported authority. The circumstance has been noticed, over and over again; and all who carefully studied Mendelssohn's method will bear witness to the fact.