America's National Game/Chapter 12

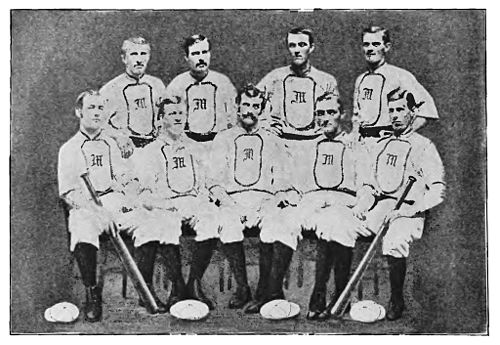

| HAYMAKERS, TROY, N. Y. | ||||

| "Mart" King, c.f. | Michael McAtee, s.s. | Thomas Abrams, p. | William Craver, c. | Steve King, l.f. |

| James Ward, 2b.Peter McCune, r.f.S. Leavenworth, 1b.Cal. Penfield, 3b. | ||||

CHAPTER XII.

1870-75

THE decade which opened with the year 1871 saw several very important events in the history of Base Ball, the first being the formal organization into a national association of the professional ball players. Heretofore professionals not only had been without an organized status, but until recently they had been under the ban of disapproval by the only recognized national association. It may be well at this point, in order to avoid confusion, to note the difference between the titles of the new and the old bodies. The earlier and first organization of Base Ball clubs was known as "The National Association of Base Ball Players." The one now organized was "The National Association of Professional Base Ball Players," with the accent on the word "professional."

The meteoric career of the Cincinnati Red Stockings had wrought a very great change in public sentiment, and in the minds of players as well, regarding professionalism. Genuine lovers of the sport, who admired the game for its real worth as an entertaining pastime and invigorating form of exercise, saw in the triumphs of the Reds the dawn of a new era in Base Ball; for they were forced, nolens volens, to recognize that professionalism had come to stay; that by it the game would be presented in its highest state of perfection; that amateurs, devoting the greater portion of their time to other pursuits, could not hope to compete with those whose business it was to play the game—and play it as a business. Hence public opposition to professional Base Ball melted quickly away. The best players needed no other incentive to make them accept the situation, even gleefully, than was found in their love for the sport, coupled with the prospect of gaining a livelihood in a manner so perfectly in accord with their tastes and inclinations.

Even before 1870, several full professional and semi-professional clubs were in existence. Aside from the Red Stockings, of Cincinnati, almost every large city had clubs whose players were directly or indirectly in receipt of forbidden emoluments from the game. In 1871 the following clubs were known as professional, and were playing in that class: Athletics, of Philadelphia; Atlantics, of Brooklyn; Bostons, of Boston; White Stockings, of Chicago; Forest Citys, of Cleveland; Forest Citys, of Rockford; Haymakers, of Troy; Kekiongas, of Fort Wayne; Marylands, of Baltimore; Mutuals, of New York; Nationals, of Washington; Olympics, of Washington; and Unions, of Morrisania.

However, at the meeting at which the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players was formed at New York, March 4th, 1871, only the following cities were represented: Boston, Brooklyn, New York, Philadelphia and Troy, in the East; Chicago, Cleveland, Fort Wayne and Bockford, in the West. At this, the first meeting of the new Association, Mr. J. W. Kerns, of Troy, President of the Haymakers, was elected President of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players.

Of the ten professional clubs entering the National Championship contest of 1871 only eight finished the season. The champion Red Stockings, of Cincinnati, had disbanded. The Kekiongas, of Fort Wayne, played no official game after July. The Eckfords, of Brooklyn, which did not enter the race until August, lost representation in the pennant contest on account of tardiness. The race closed with the clubs in the following order: Athletics, of Philadelphia; Bostons, of Boston; White Stockings, of Chicago; Haymakers, of Troy; Mutuals, of New York; Forest Citys, of Cleveland; Nationals, of Washington, and Forest Citys, of Rockford.

As showing the players who were prominent in the game at that time, and who were the first recognized professional players of Base Ball, the following list of contestants should be of interest:

Athletics, of Philadelphia—Malone, catcher; McBrido, pitcher; Fisler, first base; Reach, second base; Meyerle, third base; Radcliffe, shortstop; Cuthbert, left field; Sensenderfer, center field; Heubell, right field.

Bostons, of Boston—McVey, catcher; Spalding, pitcher; Gould, first base; Barnes, second base; Shaffer, third base; G. Wright, shortstop; Cone, left field; H. Wright, center field; Birdsall, right field; Jackson, substitute.

Eckfords, of Brooklyn—Hicks, catcher; Martin, pitcher; Allison, first base; Swandell, second base; Nelson, third base; Holdsworth, shortstop; Gedney, left field; Shelly, center field; Chapman, right field; Allison, substitute.

Forest Citys, of Cleveland—White, catcher; Pratt, pitcher; Carleton, first base; Kimball, second base; Sutton, third base; Bass, shortstop; Faber, left field; Allison, center field; White, right field.

Forest Citys, of Rockford—Hastings, catcher; Fisher, pitcher; Mack, first base; Addy, second base; Anson, third base; Fulmer, shortstop; Ham, left field; Bird, center field; Stires, right field.

Haymakers, of Troy—McGeary, catcher; McMullin, pitcher; Flynn, first base; Craver, second base; Bellan, third base; Flowers, shortstop; King, left field; Yorke, center field; Pike, right field.

Mutuals, of New York—C. Mills, catcher; Wolters, pitcher; Start, first base; Ferguson, second base; Smith, third base; Pearce, shortstop; Hatfield, left field; Eggler, center field; Patterson, right field.

Olympics, of Washington—Allison, catcher; Brainard, pitcher; Mills, first base; Sweasy, second base; Waterman, third base; Force, shortstop; Leonard, left field; Hall, center field; Berthrong, right field.

At the First Annual Convention of the National Association of Professional Ball Players, held at Cleveland, in March, 1872, Robert Ferguson, of the Brooklyn Atlantics, was elected President, and it was declared as the policy of the association not to permit any outsider—that is, anyone not a professional Base Ball player—to hold office.

Eleven clubs, from Boston, Brooklyn, Baltimore, Chicago, Cleveland, Mansfield (Conn.), New York, Philadelphia, Troy and Washington, entered for the National Championship series of 1872. Two clubs entered from Washington—the Nationals and Olympics; but the Nationals withdrew before the close of the season and had no standing in the race, which closed with clubs in the following order: Bostons, Athletics, Marylands, Mutuals, Haymakers, Forest Citys, of Cleveland; Atlantics, Olympics, Mansfields and Eckfords.

In 1873 Mr. Robert Ferguson was elected to succeed himself as President of the National Association of Professional Ball Players.

As indicating the crudity of the game as played even so late as that year (1873), it may be remarked that it was thought necessary to adopt a rule forbidding the catching of a fly ball in hat or cap, and giving the base runner his base as penalty for any ball so caught.

It was further provided by this rule, that a ball so caught became a dead ball, and could not be put in play until returned to the pitcher, in his position. I recall an amusing incident growing out of this "cap catch" rule. In those early days of Base Ball, when the game was in its formulative period, it was quite customary for bright players to study out new schemes of play that would show up defects in the playing rules, and, by applying these technicalities in a regular match, attract the attention of rule-makers and effect the desired change.

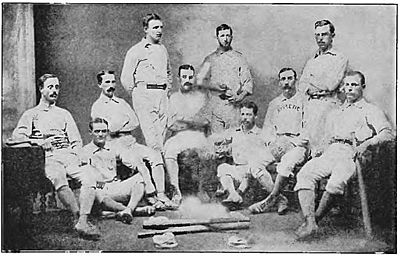

The players of our team—the Bostons—were sitting in the hotel one evening, at Cleveland, when someone, commenting on the rule, asked what would happen in case the MUTUALS, NEW YORK, N. Y.

Nelson, 3b. Martin, p. and r.f. Swandell, 2b. Eggler, c.f.

E. Mills, 1b. Hatfield, s.s. C. Mills, c. Walters, p. and r.f. Patterson, l.f.

bases were full and a ball should be caught in a cap by one of the players fielding his position. The official umpire of the pending series of games, Ellis by name, was present, and the case was put up to him for a decision. He was asked what he would rule in such an emergency. He replied, "I don't know; but I hope I may never be called upon to decide that point in a close game."

A few weeks later we were playing the Athletics at Philadelphia. We always had a hard fight in the "City of Brotherly Love," and the contest this day was particularly close and strenuous, with the local crowd very bitter against the "Bean Eaters" because of the intense rivalry between these two leading clubs.

It happened that the Athletics got three men on bases in the last innings, when the opportunity to test the "cap catch" rule presented itself to my mind. Prompted by a spirit of mischief, no doubt, I suggested to George Wright, who was near me, playing at short, that this would be a good time to try out the "cap catch" rule if an opportunity presented. I had a slow ball at that time, the delivery of which was frequently followed by a pop-fly, find this I pitched to the batsman, with the result that, sure enough, he sent a nice, easy one over to short field. Wright, reaching for his cap, deftly captured the ball therein. He then quickly passed it to me, standing in the pitcher's box. Under the rule, the ball was now in play. I threw it home, from whence it was passed to third, second and first, and judgment demanded of the umpire on the play.

As a coincidence, it happened that the umpire on duty that day was Ellis, the same with whom the subject had been discussed one night at Cleveland. The effect of the play on the crowd was simply paralyzing. None present had ever seen anything like it, and nobody knew what was up. The umpire, passing me, hissed: " That was mean of you, Spalding." The spectators were wild with rage. Shouts of " dirty ball," " Yankee trick," etc., etc., came from all quarters. Interest was at once centered on poor Ellis, the umpire. It was clear that if he declared the base runners out he would be mobbed. If he decided otherwise, he would do so in direct violation of the strict letter of the rule. Meanwhile the crowd became more and more riotous, now threatening our team, and now the umpire. Through it all I kept a stiff upper lip, demanding "judgment." "It's up to you, Mr. Umpire," I shouted. "What's your decision?"

"I decide," said he after a short pause, during which he looked into the faces of the angry mob, "that nobody's out and that the batsman must resume his place at bat as though nothing had happened."

I do not recall which team won that game, but I do recall the fact that at the close of the contest four burly policemen came on the field to escort me from the grounds.

"What's the matter now? Am I under arrest?"

"Naw, you ain't under arrest; but the management thought we'd better be on hand to protect you."

After the game was over and we had returned to our hotel, I was plied with all kinds of questions about that trick: "What about the umpire?" "Was his decision right?" and I made this reply:

"Technically, if for no other reason, he was wrong; but as a matter of policy he was right; for if he had decided otherwise than as he did there would have been a riot, and somebody would have got a sore head."

Upon mature reflection, I am convinced that the decision of Umpire Ellis in this instance was right from every standpoint; for, as umpire, it was his duty to see that the spirit as well as the letter of the law was observed, and this was a clear case where the letter of the rule had been followed but the spirit violated. Umpire Ellis' decision in this case was absolutely correct under the circumstances, for there are times in Base Ball games when an umpire is justified in going outside the rules to preserve fair play and make secure the dignity of the sport.

This incident is narrated, not so much on account of the interest attaching to it, as to indicate how the evolution of the game of Base Ball, from its crude form in the earlier days to its present degree of perfection, has been largely wrought through observation and experience of incongruous rules by players themselves.

The season of 1873 saw nine clubs entered for the championship. Only eight, however, were accorded a place at the close. Boston again won the first honor, with other clubs following in this order: Philadelphias, Marylands, Athletics, Mutuals, Atlantics, Washingtons, and Resolutes, of New Jersey. In this year Adrian C. Anson, who had heretofore played with the Forest Citys, of Rockford, and Tim Murnane appeared in the Athletic nine.

In 1874 a new rule for the playing of Base Ball was adopted. It provided for ten men and a ten innings game. The argument that led to the adoption of this rule was that, as played, the game had a lopsided field; that between first and second bases was a hole that needed protection by a second shortstop. The experiment was tried, but was soon abandoned and the rule rescinded, as the innovation had added nothing to the interest or perfection of the game.In this year, 1874, eight clubs again entered the championship contest, only one (the Chicago Club) being from the West. Eastern cities represented were Boston, Baltimore, Brooklyn, Hartford, New York and Philadelphia. The City of Brotherly Love had two clubs. Out of 232 games scheduled 96 were not played at all, clubs ignoring them, consulting only their own desires or convenience. The Bostons again led in the race, the standing at the close being as follows: Bostons, Mutuals, Athletics, Philadelphias, Chicagos, Atlantics, Hartfords and Marylands.

Thirteen clubs entered the lists in 1875 for the Association championship pennant. But the number thirteen proved to be unlucky, for the season's play was characterized by so many fiagrant abuses that it sounded the death knell of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players and opened up another important era in the game.

The pennant for the season of 1875 was again won by Boston, and for the fourth time in succession. Other clubs followed in this order: Athletics, Hartfords, St. Louis, Philadelphias, Chicagos, Mutuals, St. Louis Reds, Washingtons, New Havens, Centennials, Westerns and Atlantics.It was during this season's play that a remarkable game occurred between the Chicago White Stockings and the Hartford Dark Blues. Billy McLean, the quondam prize fighter, of Philadelphia, acted as umpire. Ten innings had been played without a run being scored on either side, when the Chicagos got in one in their half of the eleventh innings, winning by 1 to 0.

In evidence of the tremendous strides that had been taken in the playing of the game in the few years since contests were characterized by two figures on each side, and occasionally by three figures for the winners, the following record of games won by the Bostons in the contest of 1875 will be in point: Boston vs. St. Louis, 2 to 1; Hartfords, 3 to 1; Mutuals, 4 to 1; Hartfords, 3 to 2; Hartfords, 4 to 0; Hartfords, 4 to 1; Philadelphias, 4 to 3; Centennials, 5 to 0; St. Louis, 5 to 0. On the other hand, Boston was defeated by Chicago in this season's contest 1 to 0; and by the same club a second time by 2 to 0, and by St. Louis by a score of 5 to 3. Here was a demonstration of what professional Base Ball had accomplished in the improvement of the game.

In 1876 eight clubs, representing Chicago, Hartford, St. Louis, Boston, Louisville, New York, Philadelphia and Cincinnati, contested for the championship, and closed the season in the order above printed.

Next year, 1877, only six clubs comprised the circuit, and of these one (Cincinnati) forfeited its membership by non-payments. Boston again took its place as winner, the teams closing the season as appears below: Boston, Louisville, Chicago, Hartford, St. Louis.

In the following year, 1878, the Louisville, New York and Hartford clubs withdrew, but as Cincinnati had made good its shortage and been reinstated, and as Providence, Indianapolis and Milwaukee had been admitted, the circuit was again composed of six clubs, the championship season closing with the clubs in the following order: Boston, Cincinnati, Providence, Chicago, Indianapolis, Milwaukee.

In 1879, Buffalo, Cleveland, Syracuse and Troy added clubs to the contest, but, as Indianapolis and Milwaukee had withdrawn, eight clubs were left to close the season as follows: Providence, Boston, Chicago, Buffalo, Cincinnati, Syracuse, Cleveland and Troy.

Thus ends the championship story of the decade of the seventies, a story which chronologically overlaps the period that saw the death of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, and the birth of the National League of Base Ball Clubs, which must form the subject for another chapter.