America's National Game/Chapter 13

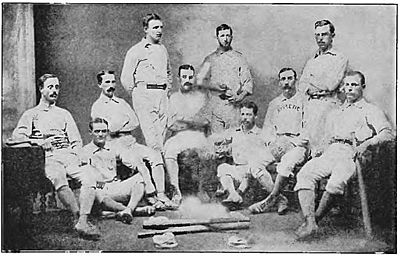

| BOSTON CHAMPIONS | ||||||

| Cal. McVey J. O'Rourke |

A. Leonard | A. G. Spalding G. Wright |

H. Wright | J. White G. Hall |

Harry Schaefer | Ross Barnes Dave Birdsall |

CHAPTER XIII.

1874

THE decade of the seventies recorded an event of considerable import to Base Ball, which chronologically belongs here. During the life of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, and before, the leading cricketers of England had been making frequent pilgrimages to the United States, with a view of exploiting Great Britain's national game, and also to win additional cricket laurels from Americans, who had become somewhat interested in the sport. Finally, in 1874, promoters of Base Ball in this country conceived the idea of returning the compliment by sending exponents of the American game to England, that the new sport might be presented in the Old Country, and perhaps gain a footing there.

While playing with the Boston team, in 1874, I became possessed with an intense yearning to cross the Atlantic. I wanted to go to England, but I hadn't the price. How to "raise the wind," therefore, was the problem I had to face. It occurred to me that since Base Ball had caught on so greatly in popular favor at home it might be worked for a special trip for me, to be followed by a second one, in which a couple of teams could be taken over to introduce the American game to European soil. I was sanguine enough to believe that, once our English cousins saw our game, it would forthwith be adopted there, as here. I didn't know our English cousins then as well as I have come to know them since.

The preliminaries were not difficult of arrangement. I had already entered into a sort of conspiracy, in collusion with Father Chadwick and other writers for the sporting press, and very soon the scheme was so urgently fostered and so successfully promoted that "the magnates" were quite convinced, and I found myself en route to England, as the avant courier of such an undertaking.

I had been provided with so many excellent letters of introduction, that upon my arrival in Britain I was able to secure an early audience at the celebrated Marylebone Cricket Club, with a membership composed very largely of members of the nobility. Upon a date appointed, I was received with utmost courtesy, and was asked to state, in open meeting, the purpose of my mission.

It should be remembered that I was at that time a mere stripling, with very little experience in business or observation of society. It goes without saying that I had not been hobnobbing with "Dooks" on this side the Atlantic, and when I found myself suddenly in the presence of so much nobility it nearly took away my breath. However, I did the best I could. I explained to them that America had just developed a new form of outdoor sport, and that, because all the world knew that the home of true sportsmanship in all its phases was England, we turned naturally to their country to exploit our game. They had been for years sending their splendid cricketers to America, and now we would like to bring over a couple of Base Ball teams, and give a few exhibitions. Of course I knew that there would be no use to come without the favor and patronage of the great Marylebone Cricket Club, but even that honor, in the interests of sport, I hoped might be forthcoming. I talked at some length and with great earnestness, because I began to feel the responsibility of my position. It was no longer a question of my personal picnic; but a sort of international problem, with the sportsmen of Great Britain possibly inviting sportsmen of America to visit them and exhibit to the old nation the new nation's adopted game. I think, in my ardor to win out, I made mention of the fact that we had some cricketers among our players, and might be able to do something in the national games of both countries.

At last I finished. I knew my face was red with the oratorical effort, and I could feel the perspiration trickling down my spinal column. Then, just as I supposed all was over except the fireworks, I saw approaching me an attenuated old fellow, of about eighty, bearing in his hand an ear trumpet as big as a megaphone. I could tell by the deference paid to the old gentleman that he was "classy," and I awaited his approach with some trepidation. He came, took a seat beside me and asked:

"Young man, will you kindly repeat to me what you have been saying to the others?"

Please remember that the Marylebone Cricket Club is composed of gentlemen. They didn't shout or scream with laughter at my plight, as a company of my fellow countrymen would have done, and as I felt perfectly assured that they would do, but even they were unable to entirely control their risibilities, for, as I began the trying task of retelling my story to His Lordship, the Deaf, I could detect here and there a smile struggling with the facial muscles of my well-bred hosts.Next day I was officially notified that the Marylebone Cricket Club would be very pleased to welcome the American Base Ball clubs, would arrange grounds for their exhibitions, and would be delighted to schedule games of Cricket to be played between American and British Cricketers. I saw that I had been too previous perhaps in suggesting the cricket contests, and when I began to "work" the newspapers, in my capacity as press agent, I found that the cricket end was altogether most attractive from their viewpoint.

Mr. Charles W. Allcock, the recognized cricket authority of England, upon whom I most depended for help along publicity lines, was especially enthusiastic about the cricket. The fact is, he didn't know an earthly thing about Base Ball, and he knew that he would be out of ammunition in a short time so far as our game was concerned. Therefore, when we arrived, late in the season, with eighteen American ball players, we found the British public thoroughly advised of the forthcoming cricket matches and only slightly informed about the exhibition ball games.

Now, it happened that, aside from Harry and George Wright and Dick McBride, and possibly two or three others, there wasn't a man in the whole American bunch who had ever played a game of cricket in his life, and most of them had never seen one. Meanwhile, the London sporting papers were promising a series of fine cricket matches—and we were certainly up against it. However, as we had eighteen men—and I urged that no one wanted to be left out of the cricket games—it was agreed that we should, in all cricket matches, play at the odds of eighteen to eleven in our favor, which, considering the fielding ability of the Americans, was greatly to our advantage.

I recall very distinctly an incident that occurred one morning preceding our first cricket match. We had gone out to practice on the Liverpool Cricket Grounds, and Mr. Allcock was present. We had hardly begun when he came to me and said:

"For Heaven's sake, Spalding, what are your men trying to do?"

I explained that they were just engaging in a little preliminary practice.

"But, man alive," he expostulated, "that isn't cricket. Why, you led me to suppose that your fellows were cricketers as well as ball players, and here have I been filling the London papers with assurances of close matches. Why, Spalding, your men don't know the rudiments of the game."

I confess that I was quite as worried as he; but this was no time to show my anxiety, and so I told him not to be uneasy. "You'll see," said I, "when the game comes off what we can do. Of course we don't pretend to play cricket in the fine, graceful form you are familiar with; but we get there, just the same. We are not much in practice, but we are great in matches."

It happened that our first contest at cricket was with the famous Marylebone "All-English" eleven, the finest cricketers in England. The game opened with the Britishers at bat. We had so many men in the field that it seemed impossible that any balls could get away, and yet, at the close of the afternoon's play, the Englishmen had scored 105 runs in their inning. Next day the game was resumed, with two of our three cricketers—Harry Wright and McBride—first at bat. Harry went out on the first ball bowled, and, after making two runs, McBride followed suit. I followed Wright, and Anson took McBride's place.

In cricket, as I knew, the duty of the batter is to defend his wicket and prevent it being bowled over. Incidentally, he is expected to hit the ball and make some runs, and, whether in defending his wicket or making his runs, he is expected to play gracefully and in "good form." I shall not undertake here to explain what "good form" requires. I gave no thought whatever to the gracefulness of my posing or to anything else than making points. The first ball that threatened my wicket I knocked over the fence, outside the grounds, and the umpire shouted: "Four runs; you needn't leave your place on a hit like that."

I had been accustomed to bat with a small, round ash club, and with the great board paddle now in my hands it just seemed impossible to miss. The second ball bowled was also hit outside the grounds, and likewise the third, and I felt myself immortalized by making twelve runs on my first "over" without leaving my position. Before I was bowled out, I had started our score with twenty-three runs, and Anson had scored fifteen runs. My experience at bat was repeated in the performances of others. The boys, seeing how easy it was, gained confidence and batted the ball all over the South of England. Harry Wright and McBride, the only members of our crowd who were accounted first-class cricketers, and who played in strictly "good form," were easy picking for the English bowlers; but George Wright put up the real thing, both as to form and achievement, and helped our score amazingly.Harry Wright was captain of the American team and an experienced cricketer of English birth. He naturally felt considerable chagrin at our lack of "form."

He was inclined to instruct our men to play carefully and guard their wickets by more "blocking" and less wild slugging. I expostulated with him on these instructions, insisting that for an American ball player to attempt to "block" as a trained cricketer would do was an utter impossibility, but that slugging, or rather lunging at every ball bowled, was our only hope of success. "Good form" in cricket requires the batsman to invariably block all balls bowled on the wicket and to strike at balls off the wicket; but in Base Ball the batsman should strike at good balls, over the plate (or wicket), and let the bad balls, or those off the wicket, go by.

This natural instinct of the ball player could not be readily changed to conform to the cricketer's custom of "blocking," so it was decided to violate all conventional cricket "form" and slug at every ball bowled. The better and more accurately the Englishmen bowled, the more hits we could make, for such balls in our eyes were what we would term "good balls."

The result was that we made 107 runs in our inning to 105 for the Britishers, and American cricket stock went soaring. The London newspapers, in commenting on the play of the American ball players, declared that while in cricket they were not up to much in "form," their batting and fielding were simply marvelous.

The history of that day's game was repeated in every subsequent contest played in Great Britain. Not once were we defeated. Following the first game, which was played at the Lords' Grounds, in London, with the above score of 107 to 105 in one inning to each side, at the Prince's Grounds we defeated the Cricket Club by 110 in one inning against 60 in their two innings. At the Richmond Grounds the game was drawn, the English cricketers being disposed of for 108 in their innings, while the Americans had 45 with only six wickets down when rain stopped the game. At Surrey Oval the ball players scored 100 in their first inning to 27 by the cricketers, the game not being played out. At Sheffield the Americans defeated a Sheffield team by 130 runs in one inning to 43 and 45, a total of 88 in their two innings. At Manchester they defeated the Manchester twelve by 221 to 95 in a two-innings game. In playing against an "AllIrish" team, at Dublin, the ball players won by 168 to 78.

The American ball players who accompanied me to Great Britain upon the occasion of this first visit of such an organization to foreign shores constituted two teams that had demonstrated their superiority in many hardfought contests. They were the players of the Boston Champions and the Philadelphia Athletics, with the following line-ups for each team:

| Bostons. | Athletics | |

| A. G. Spalding | Pitcher | J. D. McBride |

| C. McVey | Catcher | J. E. Clapp |

| J. O'Rourke and Kent | First Base | W. D. Fisler |

| Ross C. Barnes | Second Base | J. Battin |

| H. Shaffer | Third Base | E. B. Sutton |

| George Wright | Shortstop | M. H. McGeary |

| A. J. Leonard | Left Field | A. W. Gedney |

| Harry Wright | Center Field | J. F. McMullen |

| G. W. Hall | Right Field | A. C. Anson |

Thos. J. Beals, J. B. Sensenderfer, S. Wright, Jr., and Tim Murnane accompanied the teams as utility men. Mr. Chas. H. Porter, President of the Boston Club, and Mr. Ferguson, President of the Athletics, had general charge of the trip. About eighty American tourists accompanied the two clubs on this memorable tour.

The teams as above listed played in fourteen exhibitions of the American National Game of Base Ball in England and Ireland; two at Liverpool, two at Manchester, seven at London, one at Sheffield and two at Dublin. Of these the Bostons won eight and the Athletics six.

The result of this tour of American Base Ball clubs to the British Isles in its effect was even more than had been hoped for, since it elicited from the London Field, the leading sporting journal of that city, the following commendation, in addition to setting the minds of the British sporting public at work to conjecture how the Americans came to be successful in all their cricket matches:

"Base Ball is a scientific game, more difficult than many, who are in the habit of judging from the outward semblance, can possibly imagine. It is, in fact, the cricket of the American continent, considerably altered since its first origin, as has been cricket, by the yearly recourse to the improvements necessitated by the experiences of each season. In the cricket field there is sometimes a wearisome monotony that is utterly unknown in Base Ball. To watch it played is most interesting, as the attention is concentrated for but a short time, and not allowed to succumb to undue pressure of prolonged suspense. The broad principles of Base Ball are not by any means difficult of comprehension. The theory of the game is not unlike that of 'Rounders,' in that bases have to be run; but the details are in every way dissimilar. To play Base Ball requires judgment, courage, presence of mind and the possession of much the same qualities as cricket. To see it played by experts will astonish those who only know it by written descriptions, for it is a fast game, full of change and excitement, and not in the least degree wearisome. To see the best players field, even, is a sight that ought to do a cricketer's heart good, the agility, dash and accuracy of timing and catching by the Americans being wonderful."