Brown Bread from a Colonial Oven/Chapter 3

III

ABOARD A COASTING SCHOONER

Among the many steamers which line the wharves of any fair-sized port in New Zealand, there will generally be found two or three specimens of another class of vessel, less imposing to the eye, but to the fancy perhaps even more endearing—I mean the coasting schooners. Upon a sea renowned for its storms, and off a coast that bristles with dangers, these adventurous and often beautiful little boats—sea-butterflies in appearance, sea-housewives in utility, sea-heroines in pluck—flit continually back and forth, and succeed in carrying, month after month, and with a degree of punctuality surprising under the circumstances, cargoes of commodities, passengers, and news, to the tiny settlements or single homesteads which they serve as flying bridges between solitude and the world.

Towards the close of a golden summer’s evening, now several years ago, one such schooner, the Tikirau (82, Captain Fletcher), pushed and panted her way down Auckland harbour, her white wings fully spread, and her little oil-engine resolutely, for once, at work. She had done exactly the same thing many and many a time before, for she was a boat with a regular trade-route of her own; and more than once had I enviously admired from the shore the gliding of her exquisite white hull and snowy canvas, and her air—that air which belongs of right to every small craft going forth to front great seas and skies, but which always seemed to hang doubly glamorous about the Tikirau—of bravery and adventure and romance.

This time, however—this time—aha! there was a difference. No longer was she mere, remote, cold “she.” No longer must I wistfully watch her from the “steady, unendurable land.” Oh, triumph, no! From a snug, if somewhat narrow, niche upon her own deck was I this time proudly regarding her; I, yes, actually I too, was aboard! All the way down to her southernmost limit, all the way back to Hauraki, she and I—we—we, warm we, if you please—were going a-coasting together! Witness of the bravery I was to be, sharer of the adventure, in the romance. Hurrah!

She was a full boat that evening. As I looked along her deck (flush fore and aft), I wondered if ever a portion of space had been more thoroughly packed. There were the fixtures, to begin with, the galley amidship, freshly painted to an appetising pink-and-white; the wheel; and, right aft, just forward of the wheel, the low oblong roof of the “house,” with its microscopical cabins and nutshell of a saloon. And then there were the extras—and everything that term included, it would take pages to recount. From bow to stern, to begin with, the deck was overlaid with a consignment of yellow-brown kauri timber, the uppermost tier of which was fairly on a level with her rail; and on top of this were heaped and piled, lashed and carefully secured under a great tarpaulin, a multitude of queer-looking lumps, whose nature it was far from easy to determine: together with a quantity of casks, kegs, and oil-tins, many wooden cases, and a boat for some settler upon the coast—rurally converted, this last, for the time being, into an agreeable vignette of barn-door life at sea; for the bow and body of it were richly green with fine fat cabbages and cauliflowers, while the stern was shared by a black, red-ribboned cat (passenger), and a rooster in a coop. There was also a lady-like camellia, in a pot, displaying its glossy leaves just forward of the “house,” and all but concealing a certain little dark gap in the deck, and a miniature funnel close by. The gap, I found afterwards, was the entrance to a tiny engine-room; the funnel took one by the nose with a double-distilled breath of benzine, and explained itself on the spot as belonging to the little auxiliary oil-engine. It was early in the days of engines aboard such vessels as the Tikirau, and ours was something of an adventurous innovation. . . . To tell the truth, there were times when it was all adventure! Lack of pretence was its abounding virtue, and seldom, indeed, so long as I knew it, did it dissemble, by any false alacrity in starting, its deep reluctance to proceed. On the starboard beam, a beautiful whale-boat painted white, like the rest of the ship, swung from her davits; fore- and main-masts shot up burnished in the evening light, hoisted head-sails, fore-sail and main, caught and held its gold. With these, and the orderly confusion of the rigging, the very air above the deck appeared as fully occupied as the space below—which, in addition to all the inanimate objects already catalogued, found room too, as we dropped down the harbour, for the entire ship’s company, eight all told: for a little knot of passengers, respectfully keeping out of the way in the neighbourhood of the wheel; and, really to end the list at last, for a satin tabby-cat (on top of the galley), a white fox-terrier, a black retriever, and a couple of very plump pups—rioting, these last, among the men’s feet, and acquiring with howls some of the rudiments of discipline.

My fellow-passengers, it soon appeared, included a schoolmaster and his wife, returning to their charge, a native school; a storekeeper and his wife homeward-bound after a trip to town; and the rather numerous offspring of both couples. The Tikirau was their customary conveyance, and they all seemed quite at home.

“Not too much room, is there?” responded one of the ladies good-naturedly when, in shifting my position, I had to apologise for standing upon her feet as well as my own. “We shall be pretty snug below, I reckon, but it’s only a couple of days or so, is it, after all? How far down are you going? Our crowd all gets off at the first port.”

“Pretty snug,” we certainly were when it came to “turning in.” Indeed, how we actually were all stowed away, I cannot now conceive. But it was managed somehow; the Tikirau was a resourceful ship—and not resourceful only. She carried aboard of her, besides cargo and crew, a spirit of cordiality and easy comradeship, of hearty and active willingness to make the best of things, that won over into cheerfulness and “roughitability” the most fastidious, and translated every drawback into a joke.

The lights had begun to sparkle and twinkle at our heels and on either shadowy shore, before we reached the Head. We rounded it—and suddenly the city was obliterated, the lights were gone, and, in the deepening dusk, space grew about us. The engine, too, was stopped, the sea-silence fell, and, amid the silence and the darkness and the ever-widening space, the little Tikirau stole ghostlike out to sea. The voyage had begun.

I fell asleep listening to the silence, but during the night I heard from the next cabin a child’s voice, pleading pitifully for the ship to stop, “an’ I’ll walk home, mummy, I truly will!” The breeze with which we had started was, in fact, freshening considerably; and when morning came, and we staggered, those of us who could, out upon a very slantwise deck, we learned that it was blowing half a gale already, and about to blow some more; that the coast hereabouts was too dangerous to be trifled with, and that we were already running for shelter to an island close by.

It was a wild, magnificent scene. The sun was as brilliant as the wind was furious, there was not one cloud in all the great, shining sky, the sea was a flashing battlefield where the richest, most gorgeous blue imaginable strove for mastery with the brightest and most glittering white; and over the riotous waves, and before the invigorating wind, the little Tikirau was flying spiritedly along among a regular, or rather irregular, network of islands—some mere pinnacles and spits of black volcanic rock, bursting out, as it were, from the windy blue amid sharp outbursts of foam: others running out upon it, in long necks and headlands, capped with tawny turf enough to pasture a few wild goats, and low, shaggy Bush: while others again boldly reared themselves up, and braved its azure on-rush with radiant rose-coloured cliffs. All alike were uninhabited; and, for a fancy that loved adventure, as well as for an eye that loved colour and light, a better playground would have been hard to find. Then all of a sudden we ran round a bluff, and found ourselves in a small, sickle-shaped bay, deeply sunk between the horns of two high promontories, rimmed with snowy sand, and enclosing a shining crescent of smooth, sapphire water, which looked as though no breath of wind had stolen across it for a week.

There we anchored, and there we stayed all day, for the gale outside continued unabated. Inland, the cliffs ran up into great boulder-strewn hills, sparsely covered with short turf, and low manuka-scrub; and here, fossicking about for the rough-looking lumps of what, when scraped, revealed itself as kauri-gum (for kauri forest once covered all these barren isles), and setting the boulders to race each other down-hill—oh, the glorious pace they put on!—we managed to amuse ourselves well enough. From the Captain’s point of view, however, the delay was less enjoyable, and the old schoolmaster too, Mr. Quin, was already “behind his time” and anxious to get back to duty. He was, however, a gentle old man, and blessed with a remarkable talent for equanimity—the credit of which, if the crew’s demure report was to be trusted, was partly at least due to Mrs. Quin’s equally remarkable talent for giving it exercise; so presently he observed; “A bad start, my long experience has led me to believe, frequently makes a good finish. And, after all, what a sad pity it would be, supposing we were never granted any opportunity in life for being philosophical!”

Cheerfulness is, perhaps, one of the very most desirable qualities a shipmate can possess. One felt obliged to Mr. Quin. And his wife was cheerful too, never mind what her other proclivities may have been. A heartening thing it was to see that worthy woman making the best of it at meal times—“Sure, I’ve no teeth an’ no appetite, an’ a wee bit of pitaty is all I can be ’atin’ . . . an’ just a toothful of cabbage, Mr. Black. Eh? No; a little bit more than that—an’ a crust of bread, Quin; an’ mind you, now, for you cut the last too thin for annythin’ solider than a speerit—an’ now, Cap’n, I’ll just be troublin’ you for the least littlest taste more mutton, if you plase—wid a lump o’ that fat to it. Sure I’ve not much appetite; I have not.”

We got away again during the evening, and the next day made a good run past a stretch of the coast where the Tikirau did not trade. That was a capital day. The wind was now right aft, and we sailed “goose-wing,” the foresail swung out to port, the main to starboard, and the vessel shooting buoyantly forward upon an even keel, with a joyous, exhilarating motion. The boom of the mainsail thus obligingly out of the way, the house-roof suggested itself as a pleasant point of vantage, elevated, and uncrowded; and there luxuriously within a coil of rope I sat for most of the day, and revelled in my mercies. It was a world of motion—splendid, unimpeded, exultant; only to be aware of it was power; to share it was to be ten times alive. The clean wind blew and blew, and the clouds raced before it; the great merry waves leapt high into the air, as they came chasing after us, and shoals of porpoises rollicked along in the bright clear water on either side of the vessel as though they recognised in her a playmate—now vigorously rolling their bright black bulks in and out the sparkling surface, now like a company of pale green meteors streaming swiftly below and through it. (“With all our knowledge we don’t come near their power,” old Mr. Quin mused aloud, as he leaned over the side to watch them.) And, with all these forces of Nature, the little Tikirau, as she hastened along upon her routine business, with her humble and homely cargo and us humdrum folk aboard, seemed somehow freely to be one. Elemental, spontaneous, gleeful, she too appeared; she was an incarnate joy, a sea-spirit of delight, a spark of perennial and quenchless activity, somehow encased in canvas and iron and timber; she was—I don’t know what she was! but she looked like a bit of Nature; she behaved like a live thing; she felt like a friend, and I loved her! Ships are like horses and people—they have a very definite personality of their own, readily to be felt by those susceptible in such matters. And, of all the ships that I have ever known, the little Tikirau stands out in my fond remembrance as easily the kindliest, the happiest, and the sweetest-natured.

The day after this, we made our first port, and there my fellow-passengers were landed, all except the Quins. It was a picturesque little place. Mountains, clothed to the summit with thick virgin Bush, ran in a long, unbroken wall parallel with the shore, from which they were separated by a narrow stretch of tableland, treeless and low. The sea-line of this stretch was broken by the jutting forth of a small promontory, above which the white spire of a little church, a noticeable landmark, rose up from among the low clustered roofs of a native settlement. Tumbled fragments of black rock studded the foot of the promontory; the wind had fallen, and the sun, although gradually brightening, was veiled in haze; it was a morning of mauve and lavender, and the water lifted and sank in long even glassy swells, so pale as to be almost colourless.

While the whaleboat was making her first trip ashore with passengers and luggage, the rest of the crew busied themselves in preparing the next load, and the ship showed, so to speak, another side of herself, and turned, as she swung comfortably at anchor, into a market-place. The hatches were off, and all kinds of household riches began to come up out of the holds—white bags of flour, brown ones of sugar, boxes of soap and candles, cases of drapery and provisions, and “sundries” of all sorts, shapes, and sizes. The mate’s voice came up thin and distant from the main hold, deep in the depths of which he was singing out the various items as the winch hauled them up; while on deck, the purser, seated upon a cask, kept a careful tally. Everybody, I observed, engineer and cook included, was “bearing a hand” in this business of discharging; it was never, aboard that boat, natural to be so haughty and select as to stick to your own job only.

Some of the timber had already been lashed into a raft, and this, presently, was vigorously shoved over the well-greased rail, and left to drift ashore. The faint sunshine brought out all the mellow hues of the wetted planks as they rose and fell upon the waves; it dwelt pleasantly upon the green “garden” in the boat, polished the camellia leaves, slightly lit the masts as they swayed to and fro, and painted to pale gold the mainsail lying heaped in its lazy-jacks, and the fore- and head-sails drooping in gathered bunches as one sees them in the old sea-pictures. Overhead the shrouds and ratlines rocked, sharply black, upon the gentle grey sky; and the holds at one’s feet presented pits of a rich darkness. A little column of blue wood-smoke streaming up from the galley brought the Bush out to sea; Tim, the cook, splitting manuka for his stove at an odd moment of leisure, and the two pups fighting for a bone—white Floss and black Darkie had hilariously gone ashore in the boat—lent an air of real domesticity to the scene. But, ah! all the while, underneath, swung, heaved, breathed the joyous instability!

At the captain’s invitation, I went ashore with him in the “second boat,” just to have a “look round.” We were greeted by an eager assemblage—all native, with the single exception of our late shipmate, the store-keeper, who was watching the delivery of his goods—and all very smiling and gay. The arrival of the Tikirau was the event of the month, for no other vessel traded to this port, and a track along the coast was its only other link with civilisation. The sight of all these brown, bright-eyed faces waiting beside the surf carried one’s fancy clean back to the days of Captain Cook; and nothing, at a little distance, was easier than to imagine ourselves the original pakeha explorers of this shore. But the moment we landed, yesterday took to its heels, and pale fancy proved nothing of a rival to robust reality—robust, and lively!

Tall, well-built men (the Maori of this district is among the finest of his race), all in European dress: women in loose, fluttering garments of indigo, pink, or white, with the blue tattoo (is it not really rather becoming?) beneath the lower lip, a silk handkerchief over the rich, rippling hair, and rosy bloom beneath the golden-brown of their cheeks: young girls, lads, children of all ages:—the whole crowd dashed at once upon their visitors with the loudest and friendliest of welcomes. Cries of the all-embracing Tenakoutou (Here you all are!), of the discriminating Tenakoe (Here thou art!), came musically from every mouth, and there was much enthusiastic shaking of hands. The captain, it was instantly evident, was a popular and universally trusted visitor, and everybody who was anybody began at once to pour into his ear (poor man, he needed dozens, and large at that!) tidings of some unexampled need for huka, hopi, and paraoa (melodious Maorifications of sugar, soap, and flour), or inquiries as to some private consignment, such as a pipe, a walking-stick, or a hat with flowers in it; while the rest, biding their time, occupied themselves meanwhile in talk and laughter with the boat’s crew, vociferous comments upon the goods already landed, and a minute examination of each package.

Several horses, with remarkably long tails, stood patiently waiting beside a puriri tree a little way along the beach—the owners had ridden in from their scattered homes at the first word of the Tikirau’s approach; many of the women squatted in conversational groups upon the sand, and puffed at short black pipes; the younger men helped to bear the packages up the beach, the elders looked on and gave advice, and there was much excitement on the part of many dogs, of course including ours. The little Tikirau, riding so peacefully out yonder, had sent ashore quite a stir.

It was good to see that, with scarcely an exception, the children seemed to be in the best and bonniest of health; they were well-formed, well-grown, and plump. But among the grown men and women the ravages of tuberculosis were, alas! only too evident. One face I vividly remember. It was that of an old man. Pitifully emaciated, wrapt in a thick blanket for all the sunshine, which was by this time cloudless, and leaning over a stick, he stood a little aside from his active, eager neighbours and with hazel eyes paled by mortal sickness gazed wistfully, not at them, not at the bounty-bearing Tikirau, but away out over the empty sea to the void horizon—and beyond. Still in life, already he was not of it.

While the unloading, the squaring of accounts, and other general business thus proceeded on the beach, I took a tour round the settlement, Te Kaha by name. It was an excellent example of the type general upon that coast, therefore a brief description of it will be economical and save words about the rest. Its public buildings were three in number—the school-house, of the usual anti-picturesque appearance, the landmark church already mentioned, bare and clean, and the native hall or meeting-house, which was no bad type of the native race in its present transitional condition; for its roof was of grey galvanised iron, while the barge-boards of its deep eaves were richly carved with the characteristic Maori patterns, and crowned by a very fine teko-teko (carved figure), with the customary grimacing face, protruding tongue of defiance, and gleaming pawa-shell eyes. Inside, matters were more purely native. Panels of scroll-work painted in harmonious dark-blue, crimson, and white, brightened the single, long, barn-like interior; rolls of mats and blankets indicated its use at night as a community bedroom; hanks of dressed flax glistened like white silk upon the walls, and a couple of pleasant-faced women, careless, for some cause, of the ship’s arrival, were busily weaving a mat. Even here, too, however, there were incongruous traces of the pakeha. Between two of the panels, there hung a Graphic picture of one “Adeliza,” highly coloured, golden-tressed, low-bodiced, very tight-laced; several cloth jackets richly trimmed with jet hung beside it, and a large swing looking-glass, such as more generally stands upon a dressing-table, decorated the floor in the neighbourbood of the two women and emphasised, slanderously, I trust, the proportions of the passing foot.

As to the private dwellings, they were the ordinary whares, of varying size, standing in separate plots of ground, with palings of brown punga (tree-fern stem) between them, and over the palings very brightly striped blankets flung forth, most sensibly, for an airing. Streets, in our sense of the word, there were none; but little paths of grass meandered between some of the fences, and provided, no doubt, all the access needed among neighbours so near. By the sighting of the Tikirau the little town had been “emptied of its folk that pious morn.” Peace and silence brooded above the whares. Blue-gums, willows, and poplars here and there stood sentinel over the low, smokeless roofs; there were rose-trees as well as potato-blossom in some of the garden patches; while, beyond the outermost palisade of the pa, broad, fenceless fields of tasselling maize spread away towards the forest-dark hills, and before the sweet blues and purples of the now sunny sea laid an unshadowed strip of sweet and lively green.

During the afternoon we made and worked another port—a little grassy bay this time, containing in itself no buildings at all, except a kind of open barn stacked with golden maize cobs; but tapping a trade district, and possessing some special advantages. One side of it ran out into a curious little peninsula, of the usual black volcanic rock, which terminated in an island, and made of the bay a natural harbour, familiarly known aboard as the “Boarding-house.” That very same night proved its virtues; within the breakwater we lay snug, though the wind had swung round and was blowing strong from an undesirable quarter.

Morning brought with it no moderation; it was useless to think of getting out. “So much the better,” one of the men observed to me in an undertone. “Like peaches? ’Cause this is the shop for them.” And, accordingly, after breakfast nearly all of us were off ashore, and kits and sacks went with us. I have no space, and I should like to imagine that I had the power, to describe that rare ramble. We peered down from the low cliffs through black boughs of pohutukawa trees, still starred here and there with blood-red blossoms, upon the great, green, glassy combers that rolled majestically inshore, to slip suddenly over, as they neared the yellow sand, in long crashing waterfalls of snow. We scrambled through undergrowth, fought through “lawyer,” waded through fern, jumped little creeks, apostrophised supple-jacks, and from time to time kept coming out upon some unexpected open glade. Green grass would spread it with the softest carpet, and in the middle of the grass there would be a tree or two, perhaps a little grove of trees, with the rosy gold of ripe peaches glowing between the leaves.

The early missionaries, I was told, had planted these trees, which now, in the little clearings from which all other sign of human occupancy has long since departed, still flourish faithfully, and bear fruit. “Missionary,” in the North Island is frequently an alternative spelling for “sweet-brier,” which is a pest. As a matter of mere justice, therefore, I am glad to take this opportunity of pointing out that it can also spell “peaches,” which are not. We found apple-trees, too, figs, and plums along the coast, all planted by the same long-quiet hands, and grapes, I was told, later in the year might be had also for the gathering.

One very pleasant half hour of the afternoon was spent in repairing our friend Mrs. Quin, the valiant struggle of whose fourteen stone or so through the Bush had left behind her, in addition to a very fair wake, a considerable portion of petticoat. Our implements were but plain; they consisted of a sail-needle, some blue worsted with which it happened to be threaded, some green flax (throw a copper into the fountain of Trevi if you wish to revisit Rome: if you would come back home to New Zealand, sew a garment with green flax), the mate’s fingers, and every one’s ungrudging advice; but the effect they produced was striking, and it gave us great satisfaction, in spite of the heroine’s scathing “Sure, ’tis a walking piece o’ patchwork wid a bite out of ut I do be lookin’—no offence to ye, Mr. Black, for I know ye done your best!” Finally, we harnessed Floss and Darkie to our kits of peaches, and raced them home to the whaleboat across the soft sand of the beach. That was a very good day.

By the morning following the wind had shifted a point or two, and the skipper decided to put out. The engine was accordingly started, sail set, the anchor hove in, and we had just got beyond our breakwater, and well into the tumble outside, when, at one and the same moment, the wind failed, and our imp of an engine stopped dead.

So there we were, with all that spread of canvas, and our getting-out just as far advanced as to have brought us beyond shelter—helpless, and extremely close to a shore that, of a sudden, had completely lost all charm. It was an anxious moment. “If worrying would help, I would worry,” murmured gentle Mr. Quin, “but it won’t; so I don’t.” Far less “philosophical” were the rest of us, I fear; and the maker of that engine (“Engine? Darning-machine, you mean!” snorted one of the men) must have had more anxious moments than one—many more—if only half the wishes then expressed so frankly on his behalf came true. Mrs. Quin was eloquent for long time; then I suppose her conscience pricked her, for she finished with the following comfortable combination of “pious” with “natural” feeling. “Oh, lave the poor man to God! Isn’t that what my mother advised herself when a mean skunk of a fellow went an’ killed the wan little goat on her, that was all she had, bless her! to feed us childer wid? And widin’ the year, was there wan baste in all that gintlemin’s paddick but had died? There was not. Now!”

The boat meanwhile had been sent out with a kedge anchor, by means of which the Tikirau was soon warped back to a safe position; and this was no sooner accomplished than the engine, of course, started work. It puffed us forth once more into the wind with the greatest good-will, apparently, in the world, and seemed ready to go on for days. But as soon as we were well out, instead of stopping us, I am glad to say the darning-machine got stopped itself, and away with all her might (somehow, one never thought of the engine as being part of her might, or indeed part of her in any way), flew the Tikirau, bounding and dancing, swinging and leaping over the great blue hills of water like a wild thing rejoicing in liberty.

That afternoon we were able at last to land the loudly thankful Quins—Mrs. Quin’s expressions having a deeper depth than we understood at the time, for among her various bundles and kits she was slyly conveying ashore with her (“convey, the wise it call”) the greater portion of our harvest of peaches. Peace be with her! On our way back she made amends after her own fashion with a cake—made after her own fashion, also; it must have had pounds of butter in it. “That’s the worst of Ma Quin—never no reasonableness with her,” Mr. Black observed, on getting clear of his first and only mouthful. “Got a tongue o’ leather that’ll never wear out, an’ yet a heart o’ gold; do hanythink for you if you was sick—an’ then go and make you sick with truck like this ’ere. Got no moderation, the old lady hasn’t.” Well, and she was in consequence much more interesting than some people one meets, who have nothing else! I missed “Ma Quin.”

After they went I was the only woman aboard, and remained so for nearly all the rest of the trip. People have sometimes asked me whether I did not find the position awkward. Never; not a bit! there was nothing to make it so. The crew were a steady, respectable set of men—upon that point the captain was particular; I never heard a foul word from any one of them all the time I was aboard; and the Tikirau carried no liquor. “I suppose, then, you were treated as a kind of princess?” has been sometimes an alternative suggestion, to which, “Not a bit!” is again the answer. No; I was treated just as an ordinary woman is ordinarily treated in New Zealand by her male fellow-citizens—that is, with a frank friendliness; respectful because self-respecting, easy without familiarity, and probably due, partly at any rate, to the political equality of the sexes—certainly not in the very least endangered by it. Nothing, perhaps, in all New Zealand intercourse is more marked and more charming than this trait. A princess aboard the Tikirau? No, thank you! I was something infinitely more to be envied—an equal, a comrade, a shipmate; to be freely talked to, listened to, helped, confided in or laughed at, as occasion demanded—And have I ever enjoyed myself more?

A word or two now as to the individual members of the ship’s company. Skipper first, of course. Captain Fletcher was a short, wiry man, with a beard already turning grey—for a seaman ages early as to looks; essentially active both in mind and body, and in manner rather reserved, although he was excellent company when you knew him. As a man, he bore a well-merited reputation for kindliness, integrity, and, best of all, scrupulous justice; as a seaman, he had often been proved both skilful and wary. “Never knew the old man’s equal for dodging weather,” was an approving sentence that I often heard aboard the Tikirau. He had an extreme dislike to being better off in any way than his men; and, to the scandalisation of Tim, the cook-steward, who considered such a state of things “unnatural,” afterguard and foremast hands upon that democratic vessel took their meals together; nor would the skipper even permit, to Tim’s extra disgust, the least additional luxury at his end of the table. He often worked side by side with his crew; and I have known him fret at having to set one of the hands to do what he would have disliked doing himself. At the same time, so safely and completely, other things being equal, is position secured by character, he was in every conceivable way the master of his ship, and possessed, moreover, the unqualified respect of every one aboard. “When he likes,” too, I was informed, “the old man can say what he likes, an’ mean it too, and no mistake about it!” I could say a good deal more concerning Captain Fletcher; and I only do not say it because his eye may possibly fall upon these words, and I have no desire to endanger, by falling foul of that stern modesty which is another of his characteristics, a friendship won during that trip upon the Tikirau, and, I am proud to believe, flourishing still.

Next, Mr. Black, the mate—a square-set little cockney, rough in appearance, somewhat gruff of speech, all at sea as to his “h’s” and of a nature most hot-hearted and impulsive. “Jolly funny,” I learned, could Mr. Black be, when he “had a full cargo aboard”; and I did not doubt it, although happy to be spared the entertainment. On the other hand, he was easily the most domesticated sailor I have ever met. Without the faintest hesitation, it appeared, he had at a week’s notice dashed into marriage with the widowed mother of a large family, and to use his own words, “hadn’t never looked back on it neither.” “W’en we was spliced, wot’s more, we ’adn’t no more than a one arf crown between us!” he added, and seemed to think this was the crowning triumph.

“Most imprudent!” said I.

“Imprudent?” said he. “Tell you w’at. That’s twelve year ago, that is, an’ I on’y wishes it was twenty-four.” The heartiness of his tone explained these somewhat ambiguous words as a noble tribute to Mrs. Black. “Now, you jest look a-here, an’ berlieve me,” he went on with emphasis. “Merriage, w’y—merriage is orl right, I tell yer!”

“Hold on a bit! there’s two sides to every plate, chum,” objected Tim, who was also a married man. “Look at all the worries you get, an’ the responsibilities, an’ the bills, an the kiddies gettin’ sick—I got one sick now—an’———”

“An’ w’en yer gits ’ome, the pair o’ sleeves wiv two harms in ’em roun’ yer neck. An’ that’s worf it hall!” finished Mr. Black, with feeling.

Upon my spinster liberty he was wont to comment with a bitter disapproval. He only scowled when I suggested with a sigh, that the otherwise blameless existence of Mrs. Black had now blasted my prospects for ever; and used scathingly to refer to me as “the man-hater”—most unfairly, for I liked Mr. Black.

Mr. Scott, the old engineer, was hale and hearty, rosy and smiling, but somewhat taciturn and very deaf. Intercourse with him was difficult in any case, for at meals his plate received his undivided attention, and the remainder of his waking hours appeared to be spent in silent communion with his sphinx of an engine, which he never left, whether she were working or not. She had, as previously hinted, not the sweetest breath in the world; so that there was point in Mr. Anstruther’s suggestion that her adorer must have an affection of the nose as well as of the heart.

Mr. Anstruther was the purser, and a good foil in many ways to old Mr. Scott; for he was a sprightly and active young man, the impersonation of light-heartedness and good-humour, always ready for anything, work or play, and a great hand at making and appreciating practical jokes, against himself if occasion demanded—he was not particular. The puppies adored Mr. Anstruther. Cats have no sense of humour, and poor Tib did not.

Of the foremast hands the Tikirau carried three; Phil, Tom and Fritz. Tom was steady and sturdy; a silent, fair-haired fellow, and one of the best workers aboard. Phil was tall and dark, and loved a jest; he was now making his last trip down the coast—as a seaman, at least; for on the death of a relative he had lately “come into a bit of land,” and intended to turn farmer. He was a good-natured, friendly fellow, but everybody has his limit, and poor Phil’s shared his watch, wore a stout Teutonic form, and answered to the name of Fritz. None of us, I think, knew Fritz very well; he had what is known as “a queer temper.” I ventured one day to ask him about his friends in the old country. “Fräulein,” he replied, almost it seemed to me with sour satisfaction, “I haf not one friend in de vorld.” “Won’t choke nobody to swallow that,” was Phil’s comment, when he heard this sad statement. The pair were continually at loggerheads. The last time I heard of Fritz, he, too, had quitted the sea, had got married to a portly Maori dame with some land of her own, and, like Phil, had turned farmer. What a frightful thing it would be if those two farms touched!

Last of all, though by no means least important, comes Tim, the cook-steward. Tim was a half-caste, and a picturesque creature, full of contradictions and contrasts. To begin with, he had the physique of a warrior—over six feet tall he was, and broad in proportion—a noble figure of a man; yet he spent his days contentedly in housewifely dealings with pots and pans, and within quarters so narrow that I used to watch for his entrances and exits to see how he managed them. Then he had a very violent temper, very ready to be roused. “Ought to have been on deck a bit earlier,” I was told one morning, “and seen old Tim a-kicking his bread-sponge round the deck, because it hadn’t rose.” Yet at the same time no one aboard, not even Mr. Anstruther, could more positively scintillate with good humour, nor could any one ever be gentler or more patient with women, children, and dumb animals. Easily elated, again, by some very little thing, he was equally capable of enduring fits of depression. “I’d a sister once,” he told me; “she was my mainstay—it was before I married—and she died. Straight off on the bust I went, and drank for seven solid months after.” Blessedly clean about his work was Tim, and a really clever cook, too, and proud of his job. Much of our domestic harmony aboard the Tikirau was probably due to him; for although we were soon “down to tins and salt tucker,” and our meals were simple, as all meals at sea anyway ought to be, yet they were both nourishing and varied, and always interesting.

Oh! those meals aboard the Tikirau! They have not lost their relish yet. I have but to close my eyes, and the whole scene comes back to me—that little, artless saloon, fairly filled by its long centre table, with the swing tray of glasses above, and the filter in one corner: the sweet, bright air and sunshine gushing freely through the open skylight, and down the two or three steps of the companion—interrupted there, however, at times, by the massive form of Tim descending with a load of steaming dishes, or that tea-can of phenomenal size—and, round the table, all our expectant, sunburnt, shining faces, and eyes bright with the genuine sea-swing.

I can see once more the Captain at the head of that family table, gravely attentive to his paternal task of distribution; old Mr. Scott, equally absorbed in the sacred duties of consumption; Tom, his fair hair brushed carefully into a verandah above his bashful eyes; Fritz, chin to plate, silently ladling in enormous mouthfuls, more Germanico; Mr. Black, putting into his dealings with his dinner the same heartiness and dispatch which had secured him Mrs. Black; Mr. Anstruther, brimming over with some humorous nonsense or other: and Phil’s brown eyes readily responding to the joke. Yes, indeed! Our plates were not of porcelain; we drank from mugs, and there was no butter-knife; the tablecloth (yes, we had a tablecloth, boiled once a week in a kerosene-tin, hung on a backstay to dry, and ironed while yet a little damp, by the primitive process of being folded underneath a locker cushion and sat upon daily until wanted), our tablecloth lacked gloss perhaps, and our menu, as I have said, was limited, and strictly of a sea-going description: but not for the very choicest and most delicately served banquet ashore would I have exchanged one of those hearty reunions. “Aha! you know how to take the lee-side of the duff, I see,” Mr. Black was wont to say in friendly approval of my excellent appetite. Alas! I would be content to take but the weatherside, if it might only be again aboard the genial, the congenial Tikirau!

But now to get back to the trip. The same day that we landed the Quins, we succeeded, by a bit of rare good luck in the matter of wind, in rounding the chancy, or rather, unchancy, headland, that makes a sharp angle in that part of the coast-line—Cape Runaway, namely; and ran, just at nightfall, into Hicks Bay, a small, deep indentation upon its farther side. Here we had a surprise, and a pleasant one, for the riding-lights of no fewer than four other small vessels twinkled through the twilight, shot streamers of gold down through the quiet water, and lent to this remote and lonely inlet the cheerful and homelike appearance of a peopled port. The men named these boats readily from their rig. “That’s Peters in the Resolution; an’ that’s the Konini next, an’ the Coronation—ought to ha’ been in Auckland days ago; an’ the little ’un she’s the Aorere. No’therly bound, all of ’em, an’ put in here for shelter. Visitin’ cards in the cabin soon, you’ll see.”

And, sure enough, the Tikirau’s anchor was scarcely down before the plash of oars resounded alongside, and the calling had begun. Our little saloon was shortly refurnished with a tableful of quite new faces, and the evening sped away like a shot in animated discussions concerning weather, trade and—engines.

Just before sunrise next morning, while we were loading our first boat, one after another the rest all slipped past us, out upon their homeward way, for the wind had come fair. Hicks Bay is perhaps the most picturesque spot on all that picturesque coast; and a lovely sight it was that morning. A tawny, grass-grown promontory ran out upon the sea to our right, the opposite barrier was a tumble of black rocks and Bush, and the head of the bay was formed by lofty mountains, covered almost to the water’s edge with thick virgin forest. As at Te Kaha, a little white church stood out upon the shore with very precise distinctness against this dark background, and the grey, silken sea was sprinkled by the white sails of the escaping craft. Everything was clear, almost curiously clear, in the still, sober atmosphere. Then suddenly, from the sharp-ruled sea-line eastward, leapt the bright round forehead of the sun, and the daily miracle of light was wrought! Everything came instantly alive. The clearness was coloured now, the cleanness polished; visibility was radiance, movement became manifest and shone. The awakening world opened its eyes, and there was a laugh in them; all life drew a deeper breath. The breeze freshened. The ripples that ran shoreward before wind and sun were now of a lively blue, and crisped and ruffled with gold. The wide free air and sky were bright as gems—almost too bright; ashore, the black solidity of the Bush was broken and quickened into green tree-tops of a hundred tones, glossy karakas twinkled above the rocks, and the grave little white church smiled. About the sparkling bay, silvery sea-swallows now flashed and darted, and those four homely coasters running out with the wind became four visions of most aerial beauty. The Aorere passed close by; her deck and spars were of gleaming gold, her sails were cloth-of-gold; sparkles of light broke from the brass upon her wheel and the ripples at her foot; the unkempt, weather-beaten faces of her crew, turned sunward, were transfigured as if by triumph, and light flashed from heavy eyes.

By and by we rowed ashore in the whaleboat, and then I saw the Tikirau—she was the loveliest of them all! The naked, newborn radiance full upon her white hull, and broad upon the mainsail under which she was riding, there she swam upon the water like a shining sea-bird, with one gold-white wing uplifted, the quivering water-lights, blue and silver, playing upon her beautiful bows, and the gleaming glassiness below her faultless mirror. The white whaleboat, with her exquisite lines, was the worthy daughter of so beautiful a mother. I never could watch her leave the schooner’s side without appreciating afresh that old imagination of the Maoris when first they saw the pakeha frigate with her pinnace—that the one was the parent-bird and the other the fledgling.

Three loads ashore, and then we were off again; and by noon were rounding a second great cape, East Cape, off which, at a little distance, lay a precipitous and barren islet, a mere, but mighty, rock. A zigzag path toiled up it, and on the top appeared the conspicuous white building of a lighthouse, with some lower roofs huddled beside. In our small vessel, and with the breeze then blowing, we were able easily to pass between the mainland and the rock, and, as we slid close by, “Give ’em a good-day,” somebody suggested; “it’s a lonely life, that!” Every one of us, except the man at the wheel, accordingly seized something—anything that was handy, from one’s neighbour’s cap to the dinnercloth—and waved it with hearty goodwill; and immediately, as if by magic, answering white signals broke from the watchful windows and doors above.

With the glass we could pick out the forms of women and little children; one mother had a baby in her arms. A lonely life indeed! and what a setting for the impressionable days of childhood—no trees, no grass, no birds except the sea-fowl, no paddock but the flat and barren tumble of sea, no room except for the eye, and, instead of the thousand-and-one friendly and pretty details of Mother Earth, simple, sheer, uncompanionable space. No bad abiding-place perhaps for a mind stored with theories calling for arrangement, or big with thoughts demanding birth—a kind of attic, indeed, of the Universe; but what does a child make of it? and what does it make of the child? I should greatly like to know. The hardship of having to endure so anchored an existence seemed to us that day almost intolerable; for we ourselves were gloriously leaping and flying along before a gallant wind and over a sea of gleeful green and silver. There were islets of cloud in the sky, and these could travel with us; but that poor pinnacle of rock was swiftly left behind—left to rooted loneliness. Now it was a mere cloud on the horizon—now it was gone.

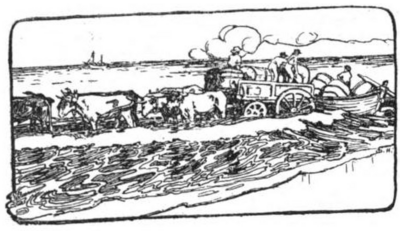

The port at which we called next had a pleasant distinction. It owned a bullock-cart. Generally speaking, upon that shallow and surf-beaten coast our men had to do a great deal of wading in the course of loading or unloading the whaleboat—weary work, with heavy kegs and cases on your back; so that it was a grateful relief at Waipiro to find a team of eight great bullocks, with a capacious cart attached, waiting in the surf for our boat-load. How picturesque they looked, too, in addition! with their wide-branched horns, and great bulks of glossy red and chestnut and black, very vivid above the vivid blue of the sea and whiteness of the surf, in the midst of which they stood patiently planted, like unusual rocks.

So the bright days ran on. Now we were at sea, now ashore; sometimes we hung off and on a little, to give the tide time to make or ebb, or the surf a chance to abate; once or twice, indeed, we were compelled to give up all hope of a landing, and to run past some expectant port or homestead; but, upon that lucky trip, not more than once or twice. Our return loads on the way down were mostly empty casks or cases (“Passenger with personal luggage,” I remember Mr. Anstruther once unkindly announcing as they brought me back from shore upon a load of empty beer-barrels); but, as we proceeded south, we began, too, to take in some bales of wool. Would you care for a succinct and accurate account of a specimen day? Here it is, then, straight out of the ship’s log, which was laboriously made up each night in the saloon by Mr. Black (pipe in mouth, elbows spread, head laid upon one shoulder, severe frown on brow—can I not see him?), and which lies before me now as I write.

“Tuesday, 12/1/19—. At 5 a.m. lowered boat and landed cargo at 6.15 finished, started engine, secured boat and anchor went on to tuparoa and landed cargo, received 18 bales of wool on board at 10 a.m. finished and went on to reparoa and landed and shipped cargo at 2 p.m. set all sail secured boat and anchor and went on to port Awanui at 4. p.m. rounded E cape, light S. wind, 8. p.m. Howerea point abeam midnight calm clear weather. Barom 30, 20 pump and sidelights carefully attended to.

“John Black, Mate.”

The scenery changed as we proceeded south; not for the better from the picturesque point of view, though perhaps a farmer’s eye might have found it more promising. The abrupt black crags and rocks of scoria gave place to the smooth smugness of papa, blank and biscuit-coloured; the proud, Bush-covered crests and deep gullies were supplanted by undulating grass-lands, treeless but for a spiky cabbage-tree here and there, a starry ngaio or so, and a good deal of tauhinu scrub, aromatic but unprofitable. A coach road, too, began to be visible, with now a trickling mob of sheep, now a vehicle or horseman proceeding along it. At Tolago Bay, Captain Fletcher showed me the place where Cook lay all one winter and overhauled his ship; as well as a strange, eerie spot in the hills near by—a sort of deep grassy crater, at the bottom of which, through a great tunnel, the sea comes washing back and forth into the very heart of the hills.

And the scenery aboard the Tikirau changed too, as we neared our southernmost port of call. The “farm-yard” boat had disappeared long before; its cabbages were now green but in memory, the cock, the cat, and the camellia had long been landed; day by day the casks diminished and the cases dwindled; day by day the leap into the whaleboat grew longer and the climb aboard more steep. There even came an hour when the final raft of timber went over the side; and at last, one fine morning, lo and behold! new-washed and immaculate, the actual planking of the deck appeared, and the vessel looked as strange as a familiar room does when all the furniture is out of it. The next day we ran into Gisborne.

At Gisborne we lay some three or four days, discharging and reloading. Then, homeward-bound, and once more with a well-piled deck, the Tikirau went out again, to trade up the coast instead of down. Places, like people, are extremely different according to the way in which you approach them; and although we steered practically the same course, and called at pretty nearly all the same ports, our passage up, nevertheless, stands out clear in my memory as quite a different trip from our passage down. We had still, however, the same brilliant weather—I remember scarcely one grey day, although plenty of rough ones—it was still an epic of brightness, a long delightful tale of “blue days at sea.”

Once we dipped our ensign, run up for the occasion, to a man-o’-war, whose trim hull and yellow funnels were dodging in and out among our remote haunts, taking soundings, we supposed; she looked like Behemoth in comparison with our insignificance. Once we sighted a whale, once we caught a young shark, and several times we had a porpoise hunt. These were quite exciting. One of the men, armed with a harpoon, would take his stand in the chains ready to strike at any polished back as it rose or rolled beneath him; another man stood by with a bowline to be slipped instantly over the tail of the “catch” by way of support, while Floss and Darkie, rigid with excitement, paws upon the rail, hindfeet on the deck, rapturously barked and squealed. Once a porpoise did get “fixed”; but the bowline was not ready at the moment, and the poor victim, breaking away from the harpoon, ripped a great square out of his back, and left a horrible stain upon the blue surface beneath which he shot away. “Pity! His mates will eat him now, an’ porpoise liver is as good as calf’s any day,” said the regretful Nimrod in the chains. “Ought to ha’ looked a bit livelier with that there line, mate. But there! ought stands for ‘nothing,’ don’t it?”

One beautiful evening we spoke another of our own fleet. We were anchored in a bay beneath mountains covered with Bush, which in one place was on fire, and sent a ruddy, pulsing glow across the sky and deep into the water. Opposite, in perfect contrast, hung the full moon, peaceful, and pure, and pale; and I was lying on the “house” roof, lulled into delicious dreaminess by the humming of the surf ashore, the wash of the water along the vessel’s side, and the satisfying loveliness all round, when—gradually—I became aware of an approaching, mystical presence; felt, rather than saw, a ghostly glimmer come gliding alongside; and there, by us, all of a sudden, in full moonlight, lay the white-winged Rongomai!

Her skipper came aboard the Tikirau and stood talking awhile on the deck; and something started him telling, in that tranquilly romantic place, a story of quite another side of the sea-life. It was a story that began with a wreck. The vessel had been thrown on her beam ends, the decks were a-wash, and the speaker, with only one other of the crew, found himself in the main-rigging, eye to eye with Death. “The chap with me was a very smart young fellow—hard case, regular pirate, an’, says he, ‘Watch below must ha’ been drowned, an’ the rest o’ watch on deck looks to be well overboard. What say,’ says he, ‘if we was to try an’ save her on our own, an’ keep her for ourselves?’ Well, she was under fore an’ main torps’ls (’twas that what done it), an’ first thing was, to get that main torps’l down. God! that was a business—aye, that was a bit of work! There she was, bangin’ about, an’ there was we, bein’ banged—flesh and blood gettin’ knocked clean out of us in lumps, though we knew nothin’ about it till next day. Every minute, thinks I, ‘We’ll never live to see another’; but hows’ever, down comes the blessed sail at last, an’ then, what with the lift o’ the sea, an’ a lick o’ wind that shifted her round, she started to right herself. An’ now here comes in the cream o’ the thing. We was beginnin’ to move a bit smart about her, and heart’n’ each other up, tellin’ what a good deal we’d made of it, when, all of a sudden, blessed if a man’s head don’t pop up from below, with the rest of him followin’! an’ then another, and another, an’ another, with all the rest o’ them—until there was both our watches out on deck, and both full, mind you, not a hand missin’! Bit of a sell, eh?—How’s the wind? Southerly draw, ain’t it?”

It must have been on the following night that we anchored opposite a great gully, or river-gorge, with a little native settlement at the mouth of it, and a small church, that, beside that great gash in the hills, and by the widespread sea, had somehow an air of facing all alone tremendous odds. The early mists were still upon the mountains, and the dew upon the seaside turf, when we landed our cargo next morning, and returned to the Tikirau. But we had barely got aboard before we noticed, streaming from the mouth of the gully, a long procession of people, some riding, others walking, and all advancing very slowly towards the church; and then the captain told us how he had heard ashore of the sudden death of a girl lately come out from England to keep house for her brothers away back there in the mountain Bush, and this was her funeral. We had finished our business at the place; and, as we bounded out again upon the brilliant sea, brightness, speed, and strength everywhere about us, light in our eyes, and full life racing through our veins, there was not one of us, I think, that was untouched. “Travelling half the world over, eh?” as Tim put it, “for this. Come all the way here, to find a grave.”

We’re-entered Hicks Bay that same evening. No friendly riding-lights were this time to be seen; but, instead, there was a wonderful sunset. Great wafts and washes of pure fire suffused the sky, here and there narrowly separated by rifts of a clear blue-green, almost icily cold; and over all this bright delirium of colour, dark wisps and featherings of cloud seemed to have been wildly flung, and now to be lying in wait, as it were, with a sort of sinister stillness. “A nice sunset, yes," said the skipper; “but, all I have against it, a windy one.” He was right, of course; and in Hicks Bay we lay, windbound, for the next five days.

What did we do all that time? Well, luckily for us, it was “a dry blow,” and one from which the bay itself was well protected; so we went ashore and visited the natives, explored the rocks and beaches, and hunted about in the Bush for peacocks’ feathers and late cherries. A shipwrecked crew had once “dossed” for days in the Bush, the men said, and we discovered their camp, and appropriated, for Tim’s benefit, some of the lumps of coal still lying about. Then every day before dinner the men enjoyed what must have been truly a glorious sport. They would put on their oldest rig—I am afraid my presence aboard was a sad drawback here—dive from the bowsprit into the clear, dancing blue below, and there swim and tumble about like so many dolphins, chasing each other round and under the vessel, and vigorously splashing the while to keep the sharks away. With what envy I watched them—I who could not swim! They used to try and persuade me to jump overboard and join them, promising not to let me drown, but I never had the nerve. I have been sorry for it ever since.

Then there was work to be done. The Tikirau had her hull painted during this enforced “lay-up,” and went out of Hicks Bay looking more of a snowy sea-swallow than ever. And there was a settler to be “removed” from his old house on one side of the bay to his new one on the other. We removed him; sitting patiently in the whaleboat while his beds and tables and chairs came casually down the breakneck track—some of them on a sledge, more of them off it—feasting upon apples from his orchard, which we roasted at a fire kindled on the rocks; and being feasted on in turns by multitudes of mosquitoes, who seemed to have been keeping Lent for years. It was the only place upon the coast where we met them, and the meeting was one they must have thoroughly enjoyed.

Phil, by the way, told a rather good mosquito yarn on this occasion. “Two skippers,” he said, “were having a kind of a talk about the mosquitoes they’d met. ‘Biggest ever I saw,’ says the one, ‘was when I was a-layin’ once off the east coast of Africa. Whoppers they was—and powerful? why, look here, now, blest if a swarm of ’em didn’t go bang through my main’s’l one day, easy as stones through a parlour window. What d’ye say to that, now?’ ‘Say?’ says skipper number two. ‘Why, I should say as how they must ha’ been the very swarm I met with once down Florida way. Whoppers as you state, and powerful, as you’d lead one to suppose; and every one o’ them with his little legs rigged out in a pair o’ canvas pants.’”

Then, too, the men used to go off frequently upon fishing excursions. While we were at sea, lines baited only with native hooks of iridescent pawa-shell trailed often from the stern, and secured us a welcome change of diet; but while we were in the bay, fresh fish, dried and drying, hung daily in the shrouds, and Tim was relieved of some anxiety as to stores. Poor old Cookie! The delay was hard upon him. “You know, I got word, last port, my little chap’s worse,” he wailed, “an’ here we are stuck up in this hole of a hole, and maybe he’s”

“Now, never you fret, Tim,” interrupted kindly little Mr. Black. “Kids is no sooner down than they’re hup. You look at my Ted, now. I was in just such another stew over him one trip—an’ you know the kind of a young devil ’e is now. Sings like a bloomin’ thrush, swears like a trooper, eats ’is five meals a day, and brings ’ome ’is money to ’is mother at the week-end reg’lar. You just take and cheer up, Timmie! It’s on’y the little born angels wot ’oists their wings so quick; and I take it you and yours ain’t fish and flesh, eh?” He backed out of the galley as he spoke, but he left Tim refreshed.

At last, too, we did get out of Hicks Bay, and round the Cape. After that a good deal of maize-shipping was done. Here and there, as we proceeded north, a smoke signal would go up ashore, the Tikirau would lie-to, and the whaleboat would fetch off the load. Sometimes the natives would come off in their own boats—I remember one that looked exactly like a flax-leaf, for it was painted bright green both inside and out, and had a gunwale of red—and our deck was full of brown faces and melodious with talk that lacked the “s.” The scene ashore meanwhile was most picturesque. Beside the open storehouses of bright yellow grain, groups of natives would be gathered about the fragrant fires of corn-cobs. Perhaps a few of the girls would be shelling maize, and a pretty sight that was. Dressed generally in dark-blue cotton, their long hair rippling glossy down their backs, they squatted beside the yellow heaps already shelled, against which their smiling faces showed like darkly sparkling jewels, and from between their brown fingers the maize fell fast from the cobs in showers of golden rain. The mothers, meanwhile, would most likely be using the signal-fire as a community cooking-stove. Roast sea-urchin I never could induce myself to taste, but steamed fish à la Maori is super-excellent, and never have I eaten more toothsome kumaras and potatoes than those taken all piping hot between the finger and thumb (one’s own) and consumed without further sauce or ceremony, upon the windy beach.

Of my many hostesses, I remember especially one. She was very, very old—nearly a hundred years old, Phil maintained—and as she advanced to greet me, I thought at first that never had I seen a wilder woman. Her face was one network of wrinkles; her hair, a remarkable reddish-brown in hue, was tied upon the top of her head in a fuzzy knot; her dress was an indescribable muddle of shawls, and perhaps her face might have been washed when she was fifty. Rich, yet scarce distinguishable at first, was the tattoo below her mouth; above it, at one corner, a cigarette stuck out. She made me heartily welcome, however, with outstretched hands full of baked karaka kernels, and a flood of talk and gestures. The talk, unhappily, I could not understand at all, and felt decidedly shy at first of the kernels; but the friendliness was irresistible: we squatted down side by side and entered into a brisk exchange of smiles.

Mr. Anstruther meanwhile, Phil, and even Tom the diffident, kept shouting out to her something in Maori to which she made always the same reply, accompanied by many shakes of her dishevelled head and a certain air of dignified protectiveness that aroused my curiosity. When at last we had parted, with much cordiality and warm handshakes, and I had got back to the boat, I asked the men what they had been saying.

“Only wanted her to rub noses with you,” said they.

“Thank you,” said I, not, I fear, without a wriggle. “And what did she say?”

“Said she wouldn’t, ’cause she didn’t believe you would like it.”

How glad I was that I had mastered my hesitation about those karaka kernels! “Lady is as lady does”; and old Harete, the unkempt, the unwashed, has remained delightful to my memory ever since as one of the most perfect hostesses I ever met, one considerate before all things of the feelings of her guest. As for a Maori estimate of European gentlehood, did you ever hear this little story, which was repeated to me by the captain? Some up-country settlers were one day speculating as to the social status of a new arrival, who himself had fixed it so high that he could not possibly get down from it to help wash the dinner-dishes. There happened to be a Maori present who solved the problem very simply. “Rangatira (real gentleman)? That fellow? No!” says this true Daniel come to judgment. “Gentleman gentleman never mind what work he do. Piggy gentleman very particular!”

Such were some of the incidents of our homeward trip. But it is with a voyage as it is with a life—you may chronicle every event, and yet leave out the essentials. The characteristic things are less the things that occasionally befall than those that continually are: and, as I look back, the main features and chief charms of that trip were just the common, everyday staples of it—the wholesome, hearty company aboard; the frankness and care-free-ness that come of living always with the open light, and air, and waters; and the inexhaustible riches of the eye. It was a life full of pictures. Day after day one woke to a different landscape (even when we were windbound, the ship’s position altered, of course, with the tide), but never to one unenlivened by a foreground liquid and shining. Day by day, hour by hour almost, there was always a different sea. Now it would be rough and bright, then bright and smooth; now streeted with gold by the early sun, now one field of broad blue, or gallant blue-and-white; silver-and-green that flashed, or bloomy hyacinth, surely the true ὀινοψ—wine-dark. Sometimes it really looked asleep and dreaming, sometimes it glittered with argosies of sunbeams—or was it with “innumerable laughter”? Now, it seemed sobbing and unquiet as with grief; now it meant business, it was stern, fierce, even ferocious; now again it lay all molten silver, soft, tranquil, and at ease. Best of all, whatever its mood, it was always itself, always the living sea—restless, tireless, great: incomprehensible, yet the dear sister-soul of Man.

Then there was the excitement of landing through the surf—the waiting in smooth water between two huge white-crested breakers; the rowing back to meet the one astern, till it hung almost over us, and swamping seemed inevitable; the sharp swing skyward of the stern; the breathless, momentary poise and pause; then, the tremendous thump down, as the great wave passed beneath the boat; and, finally, our victorious rushing shoreward, upon its swift streams of snow. There were, too, the various, felt though unseen, glories of the air, that other wide ocean whose mercies were perpetually about us—its first freshness of a morning, its sweet intensity of cleanness when we were well out at sea, its evening aromas of sun-baked turf, warm tauhinu, and spicy smoke; and the splendour of its unreined vigour, when, rounding the sails like apples and piling the bright water into hills, it dashed us along through dashing music, and motion, and spray, and whipped one’s blood to a wild, unreasoning exultation. Aye, one had three kingdoms in those days—the air, the sky, the sea; and a fourth, within; and all full to the brim with vigour.

And then there was the ship herself, real and companionable entity that she was: airy and beautiful creation somewhere between Nature and Man, and in touch with both; a marvel always, and always a friend. Seen from the shore, her white beauty drew the eye like a magnet, and gleamed like some jewel which the blue sea existed apparently only to set and so enhance; but the real heart of her beauty, as of all living things, lay in her living-ness—and that, you must be aboard to feel. I used to love to get up in the bow, to watch her sharp white stem cleaving the wide water into twin curls of crystal, and taste the purity of the immense air as she divided it by her advance; then, turning, see her whole white, lovely self, coming as it seemed, towards me. Or, from the stern, to see her go about on a breezy day—deck all aslant, wind dinting the sails into deep hollows, sun filling them with gold, and pencilling them with the dun shadows of shrouds and dangling reef-points, water all a brave and white-capped boisterous blue on this side of her, roughly dark and silver on the other. . . . And now it is “Lee O!” from the captain, as he takes the helm, and the steersman runs forward to help in letting go the headsheets. Over goes the helm, out fades the wind from the great mainsail overhead, and like a disappointed, helpless thing, all the life out of it, there it hangs, listless, flat, unlit . . . till, as she recovers the breeze, first the headsails, then the fore, and finally the mainsail fill and swell out again; again all is taut above, a great plump cheek of gold, and away and away we dance, all alive, over the buoyant water, and through the singing air. Or perhaps the boom is being gybed, and swings deliberately over above our heads, to the strain of brawny shoulders at the bitts, and a hoarse accompaniment of “Come in! Way-hay! Ay-way! Hay-ho! As she will! Now then! Again! As she must! Come in!” Or we are just coming to anchor and it is, “Haul down your outer jib!” in stentorian tones from the wheel. “Haul down outer jib,” in obedient response from the bow . . . more orders, further echoes. Then the rattling of the anchor-chain over the deck, the scamper of the hands to make down fore and main sail and, lo! the Tikirau, with her wings furled—and yet how beautiful still!—and tethered, and yet how still alive!

Often when evening came and the rest of our mates that were not on duty had turned in, the dogs and I would get up on the house roof, and there, warm between their slumbering forms, I might watch the night come on. . . . First, the late grave twilight, sky and water both fading, stars peeping out dim-eyed above the swinging trucks; then, glimmering dusk, with points of light brightening out all around, and faint wakes beginning to trail down through the guessed-at glassy swell; last, the immense Dark, powdered with sparkling constellations overhead, infinite in number, each one a world; and paved with a floor of wandering blackness, here and there streamered with light from above, and with a pathway of softest wool-white glimmering astern, jewelled by the phosphorus with green-twinkling beads and balls. And all the while, and all around, silence—perfected as it seemed, rather than broken, by the faint, pleasantly familiar ship-sounds—the movements of the wheel, the quiet creak of block and tackle, the whisper of the wind, and tapping of reef-points on the sail, the talking of the water to the side. And through the silence and the darkness the vessel, above all: the vessel, gently curtseying on her way, seeming almost to breathe beneath one as she rose and fell with the heaving of the sea-breast; such a speck in the universe, all alone, and yet so sure; a creature not seaworthy alone, but world-worthy.

But why multiply words? No summary of their details could ever give the living spirit of those sea-days, no description ever convey their incommunicable charm. The voyage finished as it had begun—emphatically, with a couple of days’ grand gale. But this time the wind was in our favour, and we flew before it. How it rained! how it roared! The mainboom, usually so serenely high overhead, was now continually sousing in and out of the wild water; the sail scooped up sea, tons of it, as well as wind; a double reef had shortly to be taken in it—and with what envy and admiration I watched my mates accomplishing the task! barefoot along the plunging boom, torn at by the wind, swamped by the sea, knocked and beaten by the canvas, but all the while, active as cats and resolute as men, steadily getting the points tied, as a matter of course.

Our last sunrise saw the Auckland windows flash. We had been away just a month. As we sailed up the harbour, “My old hen can see me now,” said Mr. Black, in the tones, if not perhaps the usual terms, of sincere affection.

“See that sheet waving out at that window there?” said Mr. Anstruther. “My mother never misses our coming in.”

“Steak and eggs for tea to-night, Tim,” stipulated Phil.

“Steak an’ eggs! Vot nonsense is zat?” growled Fritz. “Zozzages . . . big!” And Tim beamed upon them both, for he had had news at the port before that his little sick son was better. It was only the passenger who made a little private moan to herself, as we made fast to the wharf, and the jolliest holiday she had ever had in her life was over. She was but little consoled, although certainly much cheered for the moment, by the discovery among her possessions, that first night ashore, of a damp parcel insinuated somehow among them, and labelled, “A keepsake from the Tikirau,” in Mr. Anstruther’s hand. It contained a large slab of duff.

Alas, the Tikirau, beautiful and beloved! Facing so willingly all the chances of the sea, she was not spared their last extreme of tragedy. A little while ago, from the deck of a bigger but not a better vessel, bound on the same trip, Captain Fletcher pointed out to me, upon the beach near one of the little ports we had touched at that bright summer, a white, lopsided object. It looked like the hull of a boat, or part of it, turned upside down. “There,” said he, “that’s all that’s left of the Tikirau,” and neither of us said much more. Carrying, as at least I might be thankful to learn, none of her old crew, she had been caught at a dangerous anchorage, one winter’s night, by a terrible, suddenly-veering storm, and perished with every soul on board. No light without shade, it seems, even in a ship’s career. So ended, in gloom, that busy, bright, seeming-sentient existence.

But I never think of it as ended at all; in my private and particular cosmos, the world of my experience, safe for me still sails the Tikirau! Staunch, willing, and nimble, a friendly and a happy ship, there for ever she hastens upon her sparkling way, a winged and snow-white presence, bright as a sea-bird in the sunshine, or a flake of flying foam: still linking little green port with little green port along the flashing blue: still beautifying the seas, still gilding humdrum matters with romance: livening duty with beauty, buoyantly taking risks, bright, beneficent, and brave.