Eskimo Life/Chapter 4

CHAPTER IV

THE ESKIMO AT SEA

One often hears the Eskimo accused of cowardice. This is no doubt mainly due to the fact that his accusers have seen him only on land, or in fine weather at sea; and then he is too good-natured and easy-going to show any courage. It may be, too, they have not taken the trouble to place themselves in sympathy with his view of life; or else they may have called upon him to do things which he neither understood nor cared about.

If by courage we understand the tigerish ferocity which fights to the last drop of blood, even against superior force—that courage which, as Spencer says, is undoubtedly most common among the lowest races of men, and is especially characteristic of many species of animals—it must be admitted that of this the Eskimos do not possess any great share. They are too peaceable and good-natured, for example, to strike back when attacked; and therefore Europeans, ever since the time of Egede and the first missionaries, have been able to strike them with impunity and to call them cowardly. But this sort of courage is held in no great respect by the natives in Greenland, and I am afraid that they do not look up to us any the more because we exhibit a superabundance of it. They have from all time respected the beautiful Christian doctrine that if a man smite you on the right cheek, you should turn to him the left also.

But to conclude from this that the Eskimo is a coward would be unjust.

To estimate the worth of a human being, you must see him at his work. Follow the Eskimo to sea, observe him there—where his vocation lies—and you will soon behold him in another light; for, if we understand by courage that faculty which, in moments of danger, lays its plans with calmness and executes them with ready presence of mind, or which faces inevitable danger, and even certain death, with immovable self-possession, then we shall find in Greenland men of such courage as we but rarely find elsewhere.

Kaiak-hunting has many dangers.

Though his father may have perished at sea, and very likely his brother and his friend as well, the Eskimo nevertheless goes quietly about his daily work, in storm no less than in calm. If the weather is too terrible, he may be chary of putting to sea; experience has taught him that in such weather many perish; but when once he is out he goes ahead as though it were all the most indifferent thing in the world.

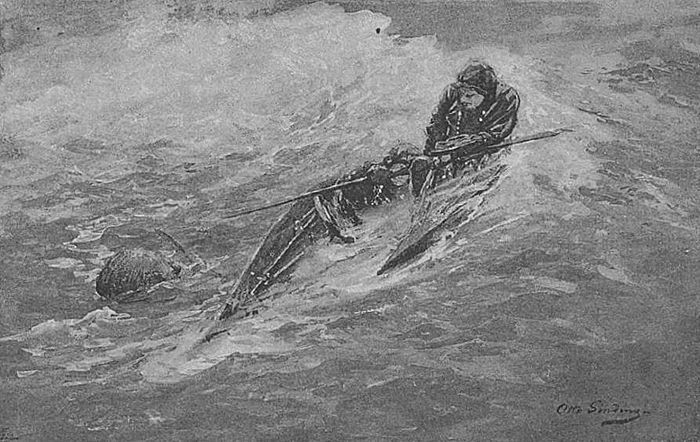

It is a gallant business, this kaiak-hunting; it is like a sportive dance with the sea and with death. There is no finer sight possible than to see the kaiak-man breasting the heavy rollers that seem utterly to engulf him. Or when, overtaken by a storm at sea, the kaiaks run for the shore, they come like black storm-birds rushing before the wind and the waves, which, like rolling mountains, sweep on in their wake. The paddles whirl through air and water, the body is bent a little forwards, the head often turned half backwards to watch the seas; all is life and spirit—while the sea around reeks like a seething cauldron. And then it may happen that when the game is at its wildest a seal pops its head up before them. Quicker than thought the harpoon is seized and rushes through the foam with deadly aim; the seal dashes away with the bladder behind it, but is presently caught and killed, and then towed onwards. Everything is done with the same masterly skill and with the same quiet demeanour. The Eskimo never dreams that he is performing feats of heroism.

Here he is great—and we? Ah, in these surroundings we are apt to seem very small.

Let us follow the Eskimo on a day's hunting.

Several hours before dawn he stands upon the outlook-rock over the village, and scans the sea to ascertain whether the weather is going to be favourable. Having assured himself on this point, he comes slowly down to his house and gets out his kaiak-jacket. His breakfast in the good old days consisted of a drink of water; now that European effeminacy has reached him too, it is generally one or two cups of strong coffee. He eats nothing in the morning; he declares that it makes him uneasy in the kaiak, and that he has more endurance without it. Nor does he take any food with him—only a quid of tobacco.When the kaiak is carried down to the beach and the hunting-weapons are ranged in their places, he slips into the kaiak-hole, makes fast his jacket over the ring, and puts out to sea. From other houses in the village his neighbours are also putting forth at the same time. It is the bladder-nose that they are after to-day, and the hunting-ground is on some banks nine miles out to the open sea.

It is calm, the smooth sea heaves in a long swell towards the rocky islets that fringe the shore, a light haze still lies over the sounds between them, and the sea-birds floating on the surface seem double their natural size. The kaiaks cut their way forwards, side by side, making only a silent ripple; the paddles swing in an even rhythm, while the men keep up an unbroken stream of conversation, and now and then burst out into merry laughter. Bird-darts are thrown in sport, now by one, now by another, in order to keep eye and hand in practice. Presently an auk comes within range of one of them; the dart speeds through the air, and the bird, transfixed, attempts, with much flapping of wings, to dive, but is held up next moment upon the point of the dart. The point is pulled out, the hunter seizes the bird's beak between his teeth, and with a strong twitch breaks its neck, then fastens it to the back part of the kaiak.

They soon leave the sounds and islets behind them and put straight out to the open sea.

After some hours' paddling, they have at last reached the hunting-ground. Great seal-heads are seen peering over the water in many directions, and the hunters scatter in search of their prey.

Boas, one of the best hunters of the village, has seen a large he-seal far off, and has paddled towards it; but it has dived, and he lies and waits for its reappearance. There! a little way before him its round black head pops up. He bends well forward, while with noiseless and wary strokes he urges the kaiak toward the seal, which lies peaceful and undisturbed, stretching its neck and rocking up and down upon the swell. But suddenly it is on the alert; it has

caught a glimpse of the flashing paddle-blade, and now looks straight at him with its great round eyes. He instantly stops paddling and sits motionless, while the way on the kaiak carries it noiselessly forward. The seal discovers nothing new to be alarmed at, and resumes its former quietude. It throws its head backwards, holds its snout straight up in the air, and bathes in the morning sun which gleams upon its black, wet skin. In the meantime the kaiak is rapidly nearing; every time the seal looks in that direction, Boas sits still and moves no muscle; but as soon as it turns its head away again, he shoots forward like a flash of lightning. He is coming within range; he gets his harpoon clear, sees that the line is properly coiled upon the stand; one stroke more and it is time to throw—when the seal quietly disappears under the water. It was notfrightened, and will consequently come up again at no great distance. He lies still and waits. But the minutes drag on; a seal can remain under water an incredible time, and it seems even longer to one who is waiting for his prey. But the Eskimo is gifted with admirable patience; he lies absolutely motionless except for his head, with which he keeps watch on every side. At last the seal's head once more appears over the water a little way off and to one side. He cautiously turns the kaiak, unobserved by his prey, and once more he shoots towards it over the mirror-like sea. But suddenly it catches sight of him again, looks at him sharply for a moment, and dives. He knows its habits, however, and at full speed he dashes towards the spot where it disappeared. Before many moments have passed it pops up its head again to look around. Now he is within range: the harpoon is seized and carried back over his shoulder, then with a strong movement, as if hurled from a steel spring, it rushes whistling from the throwing-stick, whirling the line behind it. The seal gives a violent plunge, but at the moment it arches its back to dive, the harpoon sinks into its side, and buries itself up to the shaft. A few convulsive strokes of its tail churn the water into foam, and away it goes, dragging the harpoon-line behind it towards the depths. In the meantime Boas has seized the throwing-stick between his teeth, and, quicker than thought, has thrown the bladder out of the kaiak behind him. It dances away over the surface of the sea, now and then seeming on the point of disappearing, as indeed it finally does. Before long, however, it again comes in sight, and he chases after it as quickly as his paddle can take him, snapping up on the way his

harpoon-shaft which has floated to the surface. The lance is laid ready for use. Next moment the seal comes up; infuriated at its inability to escape, it turns upon its pursuer, attacks first the bladder, which ittears to pieces, and then goes straight for the kaiak. Again Boas is within range; the animal arches its back and hurls itself forward with gaping maw, so that the water foams around it. A miss may now cost him his life; but he calmly raises his lance and sends it speeding with terrible force through the seal's mouth and out at the back of its neck. A shudder runs through it, and its head sinks; but the next moment it raises itself perpendicularly in the water, the blood pours frothing from its mouth, it gapes wildly and utters a smothered roar, while the hood over its nose is inflated to an astounding size. It shakes its head so that the lance-shaft quivers and waves to and fro; but it does not succeed in breaking it or getting free from it. A moment more and Boas's second lance has pierced through one of its fore-flappers into its lungs; the seal collapses, and the fight is over. He paddles up to its side, and as it still moves a little, he gives it a finishing stab with his long-handled knife. Then he sets quietly about pulling out his lances and replacing them in the kaiak, takes out his towing-line and blows up his towing-bladder, which he fastens to the seal, cuts the harpoon-head out and once more makes it fast to the shaft, coils the line on the stand, and takes out a new bladder and places it behind him. Next, the seal's flappers are lashed close to its body, with the thong designed for that purpose, and the animal is attached by means of the towing-line to one side of the kaiak, so that it can easily be towed along, its head being fastened to the foremost pair of thongs on the deck, and its tail to the hindmost. Now Boas is ready to look about him for more game. He is lucky, and has not paddled far before he catches sight of another seal. In an instant he has cast loose the one already killed, which is kept afloat by the towing-bladder, while he again sets off in pursuit. This one, too, he kills, after some wary stalking and eager waiting; he takes it in tow and returns for his first prey. The two great animals are fastened one on each side of the kaiak. He has now a good cargo, and cannot get very quickly through the water; but that does not prevent him from increasing his bag. As soon as another seal comes in sight those already secured are cast loose, and when the next one is killed it is fastened behind the others. In this way one man will sometimes come towing as many as four seals, or even more at a pinch.

Tobias, in the meantime, another of the best hunters of the village, has not been quite so fortunate as Boas. He began by chasing a seal which dived and did not come up again within sight. Then he set off after another; but as he is skimming over the sea towards it the huge head of a hooded seal[1]suddenly pops up right in front of the kaiak, and is harpooned in an instant. It makes a frightful wallowing and dives, the harpoon-line whirls out, but suddenly gets fouled under the bird-dart throwing-stick; the bow of the kaiak is drawn under with an irresistible rush, and before Tobias knows where he is, the water is up to his armpits, and nothing can be seen of him but his head and shoulders and the stern of the kaiak, which sticks right up into the air. It looks as if it were all over with him; those who are near him paddle with all their might to his assistance, but with scant hope of arriving in time to save him. Tobias, however, is a first-rate kaiak-man. In spite of his difficult position, he keeps upon even keel while he is dragged through the water by the seal, which does all it can to get him entirely under. At last it comes up again, and in a moment he has seized his lance and, with a deadly aim, has pierced it right through the head. A feeble movement, and it is dead. The others come up in time to find Tobias busy making his booty fast and to get their pieces of blubber from it.[2] They cannot restrain their admiration for his coolness and skill, and speak of it long afterwards. Tobias and Boas, however, are the best hunters of the village. It is related of them that, in their younger days, they were such masters of their craft that they even disdained the use of bladders. They made fast the harpoon-line round their own waist or round the kaiak-ring, and when the harpooned seal was not killed at the first stroke, they let it drag themselves and the kaiak after it instead of the bladder. This is looked upon by the Greenlanders as the summit of possible achievement, but there are very few who attain such mastery.

Hitherto the weather has been fine, the glassy surface of the sea has been heaving softly under the rising sun. But in the course of the last hour or two, black and threatening banks of clouds have begun to draw up over the southern horizon. Just as Tobias has made fast his seal, a distant roar is heard and a sort of steam can be seen rising over the sea to the southward. It is a storm approaching, and the steam is the flying spray which it drives before it. Of all winds, the Greenlanders fear the south wind (nigek) most, for it is always violent and sets up a heavy sea.

The thing is now to get under the land as quickly as possible. Those who have no seals in tow have the best of it, yet they try to keep with the others. One relieves Boas of one of his seals. They have not paddled far before the storm is upon them; it thrashes the water to foam as it approaches, and the kaiak-men feel it on their backs, like a giant lifting and hurling them forward. The sport has now turned to earnest; the seas soon tower into mountains of water and break and welter down upon them. They are making for the land with the windnearly abeam; but they are still far off, they can see nothing around them for the spray, and almost every wave buries them so that only a few heads, arms, and ends of paddles can be seen above the combs of froth.

Here comes a gigantic roller—they can see it shining black and white in the far distance. It towers aloft so that the sky is almost hidden. In a moment they have stuck their paddles under the thongs on the windward side and bent their bodies forward so that the crest of the wave breaks upon their backs. For a second almost everything has disappeared; those who are further a-lee await their turn in anxiety; then the billow passes, and once more the kaiaks skim forward as before. But such a sea does not come singly; the next will be worse. They hold their paddles flat to the deck and projecting to windward, bend their bodies forward, and at the moment when the white cataract thunders down upon them they hurl themselves into its very jaws, thus somewhat breaking its force. For a moment they have again disappeared—then one kaiak comes up on even keel, and presently another appears bottom upwards. It is Pedersuak (i.e. the big Peter) who has capsized. His comrade speeds to his side, but at the same moment the third wave breaks over them and he must look out for himself. It is too late—the two kaiaks lie heaving bottom upwards. The second manages to right himself, and his first thought is for his comrade, to whose assistance he once more hastens. He runs his kaiak alongside of the other, lays his paddle across both, bends down so that he gets hold under the water of his comrade's arm, and with a jerk drags him up upon his side, so that he too can get hold of the paddle and in an instant raise himself upon even keel. The water-tight jacket has come a little loose from the ring on one side and some water has got in; not so much, however, but that he can still keep afloat. The others have in the meantime come up; they get hold of the lost paddle, and all can again push forward.

It grows worse and worse for those who have seals in tow; they lag far behind, and the great beasts lie heaving and jarring against the sides of the kaiaks. They think of sacrificing their prey, but one

difficult sea passes after another, and they will still try to hang on for a while. The proudest moments in a hunters life are those in which he comes home towing his prey, and sees his wife's, his daughter's, and his handmaiden's happy faces beaming upon him from the shore. Far out at sea he already sees them in his mind's eye, and rejoices like a child. No wonder that he will not cast loose his prey save at the direst pinch of need.After passing through many ugly rollers, they have at last got under the land. Here they are somewhat protected by a group of islands lying far to the southward. The seas become less violent, and, as they gradually get further in, they push on more quickly for home over the smoother water.

In the meantime the women at home have been in the greatest anxiety. When the storm arose they ran up to the outlook-rock or out upon the headlands, and stood there in groups gazing eagerly over the angry sea for their sons, husbands, fathers, and brothers. So they stand watching and shivering, until, with eyes rendered keener by anxiety, they at last discern what seem like black specks approaching from the horizon, and the whole village echoes to one glad shout: 'They are coming! They are coming!'They begin to count how many there are; two are missing! No, there is one of them! No, they are all there! They are all there!

They soon begin to recognise individuals, partly by their method of paddling, partly by the kaiaks, although as yet they are little more than tiny dots. Suddenly there sounds a wild shout of joy: 'Boase kaligpok!' ('Boas is towing')—him they easily identify by his size. This joyful intelligence passes from house to house, the children rush around and shout it in through the windows, and the groups upon the rocks dance for joy, Then comes a new shout: 'Ama Tobiase kaligpok!' ('Tobias too is towing'); and this news likewise passes from house to house. Next is heard: 'Ama Simo kaligpok!' 'Ama David kaligpok!' And now again comes another swarm of women out of the houses and up to the rocks to look out over the sea breaking white against the islets and cliffs, where eleven black dots can now and then be seen far out amid the rolling masses of water, moving slowly nearer.

At last the leading kaiaks shoot into the little bight in front of the village. They are those who have no seals. Lightly and with assured aim one after the other dashes up on the flat beach, carried high upon the crest of the waves. The women stand ready to receive them and to draw them further up.

Then come those who have seals in tow; they must proceed somewhat more cautiously. First, they cast loose their prey and see that it comes to the hands of the women on shore. Then they themselves make for the land. When once they have got out of the kaiak, they, like the first comers, pay no heed to anything but themselves and their weapons, which they carry to their places above high-water mark. They do not even look at their prey as it lies on the shore. From this time forward all work in connection with the 'take' falls to the share of the women.

The men go to their homes, take off their wet clothes and put on their indoor dress, which, as we have seen, was in the heathen times exceedingly airy, but has now become more visible.

Then at last comes the first meal of the day; but it does not begin in earnest till the day's 'take' is boiled and served up in a huge dish placed in the middle of the floor. Then there disappear incredible quantities of flesh and raw blubber.

When hunger is appeased, the women always set themselves to some household work, sewing or the like, whilst the men give themselves up to well-earned laziness, or attend a little to their weapons, hang up the harpoon-line to dry, and so forth.

Then the hunters begin to relate the events of the day, the family listening eagerly, especially the boys. The narrative is sober, with none of that boasting or striving to impress the hearers with an exaggerated idea of the difficulties overcome, in which we Europeans, under similar circumstances, would often indulge.

But at the same time it is lively and picturesque, with a peculiar breadth of colouring. Experiences are described with illustrative gestures, and, as Dalager says: "When they have come so far in the story that the cast has to be depicted, they swing the right arm in the air while the left is held straight out to represent the animal. Then the demonstration goes on as follows: 'When the time came for using the harpoon, I looked to it, I took it, I seized it, I gripped it, I had it fast in my hand, I balanced it'—and so forth. This alone may go on for several minutes, until at last the hand sinks to represent the throw; and after that they do not forget to make note of the last twitches given by the seal."

At other times the most remarkable events are dismissed in a few words. But as often as an opportunity presents itself, a broad humour enters into the narration, and is unfailingly rewarded by shrieks of laughter from the eager listeners. No more perfect picture could be imagined of happy family life.

So the days pass for the Eskimo. Although there is nothing unusual in experiences such as these, they have for him a distinct attraction. His best thoughts are wedded to the sea, the hard life upon it is for him the kernel of existence—and when he is forced to remain at home, his heart is heavy. But when he grows old—ah, then the saga is over. There is always a melancholy in old age, and nowhere more than here. These kindly old men have also in their day known strength and youth—times when they were the pillars of their little society. Now they have only the memories of that life left to them, and they must let themselves be fed by others. But when the young people come home from sea with their booty, they, too, hobble down to the beach to receive them; even if it were but a poor foreigner like me, they were glad to be able to help me ashore with my kaiak. And then when evening comes they set themselves to story-telling; adventure follows adventure, the past comes to life again, and the young people are spurred on to action.

The hunting is often more dangerous than that described above. It will easily be understood that from his constrained position in the kaiak, which does not permit of much turning, the limiter cannot throw backwards or to the right. If, then, a wounded seal suddenly attacks him from these quarters, it requires both skill and presence of mind to elude it or to turn so quickly as to aim a fatal throw at it before it has time to do him damage. It is just as bad when he is attacked from below, or when the animal suddenly shoots up close at his side, for it is lightning-like in its movements and lacks neither courage nor strength. If it once gets up on the kaiak and capsizes it, there is little hope of rescue. It will often attack the hunter under water, or throw itself upon the bottom of the kaiak and tear holes in it. In such a predicament, it needs very unusual self-mastery to preserve the coolness necessary for recovering oneself upon even keel and renewing the fight with the furious adversary. And yet it sometimes happens that after being thus capsized the kaiak-man brings the seal home in triumph.

A still more terrible adversary is the walrus; therefore there are generally several in company when they go walrus-hunting, so that one can stand by another if anything should happen. But often enough, too, a single hunter will attack and overcome this monster.

The walrus, I need scarcely say, is a huge animal of as much as 16 feet (5 metres) in length, with a thick and tough hide, a deep layer of blubber, a terribly hard skull, and a powerful body. There needs, then, a sure and strong arm to kill it. The walrus has the habit, as soon as it is attacked, of turning upon its assailant, and will often, with its ugly tusks, make itself exceedingly unpleasant. If there are several walruses in a flock, they will very likely surround him and attack him all at once.Even the Norwegian hunters, who go after the walrus in large, strong boats, each containing many men, armed with guns, lances, and axes—even they stand much in awe of it.

How much more courage and skill does it require for the Eskimo to attack it in his frail skin canoe, with his light ingenious projectiles—and alone!

But this is no unusual occurrence for the Eskimo. He fights out his fight with his dangerous adversary; calmly, with his lance ready poised for throwing, he awaits its attack, and, coolly seizing his advantage, he at the right moment plunges the weapon into its body.

Coolness is more than ever essential in walrus-hunting, for the most unforeseen difficulties may arise; and catastrophes are by no means rare. At Kangamiut, some years ago, a kaiak was attacked from below, and a long walrus-tusk was suddenly thrust through its bottom, through the man's thigh, and right up through the deck. His comrades at once rushed to his assistance, and the man was rescued and helped ashore.

Besides these animals, the Eskimo also attacks whales from his little kaiak. There is one species in particular which is more dangerous than any other—the grampus, or, as he calls it, ardluk. With its strength, its swiftness, and its horrible teeth, if it happens to take the offensive, it can make an end of a kaiak in an instant. Even the Eskimo fears it; but that does not prevent him from attacking it when opportunity offers.

In former times they limited the larger whales as well, using, however, the great woman-boats, with many people in them, both men and women. For this sort of whale-hunting, says Hans Egede, 'they get themselves up in their greatest finery as if for a marriage, for otherwise the whale will avoid them; he cannot endure uncleanliness.' The whale was harpooned, or rather pierced with a big lance, from the bow, and it sometimes happened that with a whisk of its tail it would crush the boat or capsize it. The men were often so daring as to jump on the whale's back, when it began to be exhausted, in order to give it a finishing stroke. This method of hunting is now unusual.

It is not only the larger animals that expose the Eskimo to danger. Even in ordinary fishing—for example, for halibut—disasters may happen. If one has not taken care to keep the line clear, and it gets fouled in one place or another, while the strong fish is making a sudden dash for the bottom, the crank kaiak is easily enough capsized. Many have met their end in this way.But we must not dwell too long on the shady sides of life. I hope I have succeeded in giving the reader a slight impression of the life of the Eskimo at sea, and of some of the dangers which are his daily lot—enough, perhaps, to have convinced him that this race is not lacking in courage when it comes to the pinch, nor in endurance and cool self command.

But the Eskimo has more than this; when disaster overtakes him, he will often show the rarest endurance and hardihood. In spite of the many dangers and sufferings inseparable from his industry, he devotes himself to it with joy. If the history of the Eskimos had ever been written, it would have been one long series of feats of courage and fortitude; and how much moving self-sacrifice and devotion to others would have had to be recorded! How many deeds of heroism have been irrecoverably forgotten! And this is the people whom we Europeans have called worthless and cowardly, and have thought ourselves entitled to despise.