from an ancient monument. It contains seven long and seven shorter rods or bars, the former having four perforated beads running on them and the latter one. The bar marked I indicates units, X tens, and so on up to millions. The beads on the shorter bars denote fives,—five units, five tens, &c. The rod Θ and corresponding short rod are for marking ounces; and the short quarter rods for fractions of an ounce.

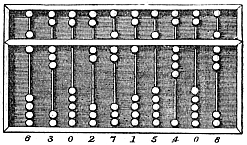

The Swan-Pan of the Chinese (fig. 2) closely resembles the Roman abacus in its construction and use. Computations are made with it by means of balls of bone or ivory running on slender bamboo rods, similar to the simpler board, fitted up with beads strung on wires, which is employed in teaching the rudiments of arithmetic in English schools.

Fig. 2.—Chinese Swan-Pan.

The name of “abacus” is also given, in logic, to an instrument, often called the “logical machine,” analogous to the mathematical abacus. It is constructed to show all the possible combinations of a set of logical terms with their negatives, and, further, the way in which these combinations are affected by the addition of attributes or other limiting words, i.e. to simplify mechanically the solution of logical problems. These instruments are all more or less elaborate developments of the “logical slate,” on which were written in vertical columns all the combinations of symbols or letters which could be made logically out of a definite number of terms. These were compared with any given premises, and those which were incompatible were crossed off. In the abacus the combinations are inscribed each on a single slip of wood or similar substance, which is moved by a key; incompatible combinations can thus be mechanically removed at will, in accordance with any given series of premises. The principal examples of such machines are those of W. S. Jevons (Element. Lessons in Logic, c. xxiii.), John Venn (see his Symbolic Logic, 2nd ed., 1894, p. 135), and Allan Marquand (see American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1885, pp. 303–7, and Johns Hopkins University Studies in Logic, 1883).

ABADDON, a Hebrew word meaning “destruction.” In poetry it comes to mean “place of destruction,” and so the underworld or Sheol (cf. Job xxvi. 6; Prov. xv. 11). In Rev. ix. 11 Abaddon (Ἀβαδδών) is used of hell personified, the prince of the underworld. The term is here explained as Apollyon (q.v.), the “destroyer.” W. Baudissin (Herzog-Hauck, Realencyklopädie) notes that Hades and Abaddon in Rabbinic writings are employed as personal names, just as shemayya in Dan. iv. 23, shāmayim (“heaven”), and mākōm (“place”) among the Rabbis, are used of God.

ABADEH, a small walled town of Persia, in the province of Fars, situated at an elevation of 6200 ft. in a fertile plain on the high road between Isfahan and Shiraz, 140 m. from the former and 170 m. from the latter place. Pop. 4000. It is the chief place of the Abadeh-Iklid district, which has 30 villages; it has telegraph and post offices, and is famed for its carved wood-work, small boxes, trays, sherbet spoons, &c., made of the wood of pear and box trees.

ABAE (Ἄβαι), a town in the N.E. corner of Phocis, in Greece, famous in early times for its oracle of Apollo, one of those consulted by Croesus (Herod. i. 46). It was rich in treasures (Herod. viii. 33), but was sacked by the Persians, and the temple remained in a ruined state. The oracle was, however, still consulted, e.g. by the Thebans before Leuctra (Paus. iv. 32. 5). The temple seems to have been burnt again during the Sacred War, and was in a very dilapidated state when seen by Pausanias (x. 35), though some restoration, as well as the building of a new temple, was undertaken by Hadrian. The sanctity of the shrine ensured certain privileges to the people of Abae (Bull. Corresp. Hell. vi. 171), and these were confirmed by the Romans. The polygonal walls of the acropolis may still be seen in a fair state of preservation on a circular hill standing about 500 ft. above the little plain of Exarcho; one gateway remains, and there are also traces of town walls below. The temple site was on a low spur of the hill, below the town. An early terrace wall supports a precinct in which are a stoa and some remains of temples; these were excavated by the British School at Athens in 1894, but very little was found.

See also W. M. Leake, Travels in Northern Greece, ii. p. 163; Journal of Hellenic Studies, xvi. pp. 291-312 (V. W. Yorke). (E. Gr.)

ABAKANSK, a fortified town of Siberia, in the Russian government of Yeniseisk, on the river Yenisei, 144 m. S.S.W. of Krasnoyarsk, in lat. 54° 20′ N., long. 91° 40′ E. This is considered the mildest and most salubrious place in Siberia, and is remarkable for certain tumuli (of the Li Kitai) and statues of men from seven to nine feet high, covered with hieroglyphics. Peter the Great had a fort built here in 1707. Pop. 2000.

ABALONE, the Spanish name used in California for various species of the shell-fish of the Haliotidae family, with a richly coloured shell yielding mother-of-pearl. This kind of Haliotis is also commonly called “ear-shell”, and in Guernsey “ormer” (Fr. ormier, for oreille de mer). The abalone shell is found especially at Santa Barbara and other places on the southern Californian coast, and when polished makes a beautiful ornament. The mollusc itself is often eaten, and dried for consumption in China and Japan.

ABANA (or Amanah, classical Chrysorrhoas) and PHARPAR, the “rivers of Damascus” (2 Kings v. 12), now generally identified with the Barada (i.e. “cold”) and the Aʽwaj (i.e. “crooked”) respectively, though if the reference to Damascus be limited to the city, as in the Arabic version of the Old Testament, Pharpar would be the modern Taura. Both streams run from west to east across the plain of Damascus, which owes to them much of its fertility, and lose themselves in marshes, or lakes, as they are called, on the borders of the great Arabian desert. John M‘Gregor, who gives an interesting description of them in his Rob Roy on the Jordan, affirmed that as a work of hydraulic engineering, the system and construction of the canals, by which the Abana and Pharpar were used for irrigation, might be considered as one of the most complete and extensive in the world. As the Barada escapes from the mountains through a narrow gorge, its waters spread out fan-like, in canals or “rivers,” the name of one of which, Nahr Banias, retains a trace of Abana.

ABANCOURT, CHARLES XAVIER JOSEPH DE FRANQUEVILLE D’, (1758–1792), French statesman, and nephew of Calonne. He was Louis XVI.’s last minister of war (July 1792), and organized the defence of the Tuileries for the 10th of August. Commanded by the Legislative Assembly to send away the Swiss guards, he refused, and was arrested for treason to the nation and sent to Orleans to be tried. At the end of August the Assembly ordered Abancourt and the other prisoners at Orleans to be transferred to Paris with an escort commanded by Claude Fournier, “the American.” At Versailles they learned of the massacres at Paris, and Abancourt and his fellow-prisoners were murdered in cold blood on the 8th of September 1792. Fournier was unjustly charged with complicity in the crime.

ABANDONMENT (Fr. abandonnement, from abandonner, to abandon, relinquish; abandonner was originally equivalent to mettre à bandon, to leave to the jurisdiction, i.e. of another, bandon being from Low Latin bandum, bannum, order, decree, “ban”), in law, the relinquishment of an interest, claim, privilege or possession. Its signification varies according to the branch of the law in which it is employed, but the more important uses of the word are summarized below.

Abandonment of an Action is the discontinuance of proceedings commenced in the High Court of Justice either because the plaintiff is convinced that he will not succeed in his action or for other reasons. Previous to the Judicature Act of 1875, considerable latitude was allowed as to the time when a suitor might abandon his action, and yet preserve his right to bring another action on the same suit (see Nonsuit); but since 1875 this right has been considerably curtailed, and a plaintiff who