Popular Science Monthly/Volume 55/August 1899/Do Animals Reason?

| DO ANIMALS REASON? |

By EDWARD THORNDIKE, Ph. D.

PROBABLY every reader who owns a dog or cat has already answered the question which forms our title, and the chance is ten to one that he has answered, "Yes." In spite of the declarations of the psychologists from Descartes to Lloyd Morgan, the man who likes his dog and the woman who pets a cat persist in the belief that their pets carry on thinking processes similar, at least in kind, to our own. And if one has nothing more to say for the opposite view than the stock arguments of the psychologists, he will make few converts. A series of experiments carried on for two years have, I hope, given me some things more to say—some things which may interest the believer in reason in animals, even if they do not convert him.

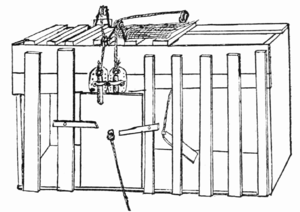

In trying to find out what sort of thinking animals were capable of I adopted a novel but very simple method. Dogs and cats were shut up, when hungry, in inclosures from which they could escape by performing some simple act, such as pulling a wire loop, stepping on a platform or lever, clawing down a string stretched across the inclosure, turning a wooden button, etc. In each case the act set in play some simple mechanism which opened the door. A piece of fish or meat outside the inclosure furnished the motive for their attempts to escape. The inclosures for the cats were wooden boxes, in shape and appearance like the one pictured in Fig. 1, and were about 20 X 15 X 12 inches in size. The boxes for the dogs (who were rather small, weighing on the average about thirty pounds) were about 40 X 22 X 22. By means of such experiments we put animals in situations seeming almost sure to call forth any reasoning powers they possess. On the days when the experiments were taking place they were practically utterly hungry,  Fig. 1. and so had the best reasons for making every effort to escape. As a fact, their conduct when shut up in these boxes showed the utmost eagerness to get out and get at the much-needed food. Moreover, the actions required and the thinking involved are such as the stories told about intelligent animals credit them with, and, on the other hand, are not far removed from the acts and feelings required in the ordinary course of animal life. It would be foolish to deny reason to an animal because he failed to do something (e. g., a mathematical computation) which in the nature of his life he would never be likely to think about, or which his bones and muscles were not fitted to perform, or which, even by those who credit him with reason, he is never supposed to do. So the experiments were arranged with a view of giving reasoning every chance to display itself if it existed.

Fig. 1. and so had the best reasons for making every effort to escape. As a fact, their conduct when shut up in these boxes showed the utmost eagerness to get out and get at the much-needed food. Moreover, the actions required and the thinking involved are such as the stories told about intelligent animals credit them with, and, on the other hand, are not far removed from the acts and feelings required in the ordinary course of animal life. It would be foolish to deny reason to an animal because he failed to do something (e. g., a mathematical computation) which in the nature of his life he would never be likely to think about, or which his bones and muscles were not fitted to perform, or which, even by those who credit him with reason, he is never supposed to do. So the experiments were arranged with a view of giving reasoning every chance to display itself if it existed.

What, now, would we expect to observe if a reasoning animal, who is surely eager to get out, is put, for example, into a box with a door arranged so as to fall open when a wooden button holding it at the top (on the inside) is turned from its vertical to a horizontal position? We should expect that he would first try to claw the whole box apart or to crawl out between the bars. He would soon realize the futility of this and stop to consider. He might then think of the button as being the vital point, or of having seen doors open when buttons were turned. He might then poke or claw it around. If after he had eaten the bit of fish outside he was immediately put in the box again he ought to remember what he had done before, and at once attack the button, and so ever after. It might very well be that he would not, when in the box for the first time, be able to reason out the way to escape. But suppose that, in clawing, biting, trying to crawl through holes, etc., he happened to turn the button and so escape. He ought, then, if at once put in again, this time to perform deliberately the act which he had in the first trial hit upon accidentally. This one would expect to see if the animal did reason. What do we really see?

To save time we may confine ourselves to a description of the twelve cats experimented with, adding now that the dogs presented no difference in behavior which would modify our conclusions. The behavior of all but No. 11 and No. 13 was practically the same. When put into the box the cat would show evident signs of discomfort and of an impulse to escape from confinement. It tries to squeeze through any opening; it claws and bites at the bars; it thrusts its paws out through any opening, and claws at everything it reaches; it continues its efforts when it strikes anything loose and shaky; it may claw at things in the box. The vigor with which it struggles is extraordinary. For eight or ten minutes it will claw and bite and squeeze incessantly. With No. 13, an old cat, and No. 11, an uncommonly sluggish cat, the behavior was different. They did not struggle vigorously or continually. (In the experiments it was found that these two would stay quietly in the box for hours, and I therefore let them out myself a few times, so that they might associate the fact of being outside with the fact of eating, and so desire to escape. When this was done, they tried to get out like the rest.) In all cases the instinctive struggle is likely to succeed in leading the cat accidentally to turn the button and so escape, for the cat claws and bites all over the box. These general clawings, bitings, and squeezings are of course instinctive, not premeditated. The cats will do the same if in a box with absolutely no chance for escape, or in a basket without even an opening—will do them, that is, when they are the foolishest things to do. The cats do these acts for just the same reason that they suck when young, propagate when older, or eat meat when they smell it.

Each of the twelve cats was tried in a number of different boxes,

and in no case did I see anything that even looked like thoughtful

contemplation of the situation or deliberation over possible ways of

winning freedom. Furthermore, in every case any cat who had

thus accidentally hit upon the proper act was, after he had eaten

the bit of fish outside, immediately put back into the box. Did he

then think of how he had got out before, and at once or after

a time of thinking repeat the act? By no means. He bursts out into the same instinctive activities as before, and may even fail this time to get out at all, or until a much longer period of miscellaneous scrabbling at last happens to include the particular clawing or poking which works the mechanism. If one repeats the process, keeps putting the cat back into the box after each success, the amount of the useless action gradually decreases, the  Fig. 2. right movement is made sooner and sooner, until finally it is done as soon as the cat is put in. This sort of a history is not the history of a reasoning animal. It is the history of an animal who meets a certain situation with a lot of instinctive acts. Included without design among these acts is one which brings freedom and food. The pleasurable result of this one gradually stamps it in in connection with the situation "confinement in that box," while their failure to result in any pleasure gradually stamps out all the useless bitings, clawings, and squeezings. Thus, little by little, the one act becomes more and more likely to be done in that situation, while the others slowly vanish. This history represents the wearing smooth of a path in the brain, not the decisions of a rational consciousness.

Fig. 2. right movement is made sooner and sooner, until finally it is done as soon as the cat is put in. This sort of a history is not the history of a reasoning animal. It is the history of an animal who meets a certain situation with a lot of instinctive acts. Included without design among these acts is one which brings freedom and food. The pleasurable result of this one gradually stamps it in in connection with the situation "confinement in that box," while their failure to result in any pleasure gradually stamps out all the useless bitings, clawings, and squeezings. Thus, little by little, the one act becomes more and more likely to be done in that situation, while the others slowly vanish. This history represents the wearing smooth of a path in the brain, not the decisions of a rational consciousness.

We can express graphically the difference between the conduct of a reasoning animal and that of these dogs and cats by means of a time-curve.  Fig. 3. If, for instance, we let perpendiculars to a horizontal line represent each one trial in the box, and let their heights represent in each trial the time it took the animal to escape (each three millimetres equaling ten seconds), the accompanying figure (Fig. 2) will tell the story of a cat which, when first put in, took sixty seconds to get out; in the second trial, eighty; in the third, fifty; in the fourth, sixty; in the fifth, fifty; in the sixth, forty, etc. This figure represents what did actually happen with one cat in learning a very easy act. Suppose the cat had, after the third accidental success, been able to reason. She would then have the next time and in all succeeding times performed the act as soon as put in, and the figure would have been such as we see in Fig. 3. The thing is still clearer if, instead of drawing in the perpendiculars, we draw only a line joining their tops. Fig. 4 shows, then, the curve for the real history, and Fig. 5 shows the abrupt descent, due to a rational comprehension of the situation. I kept an accurate record of the time, in seconds, taken in every trial by every cat in every box, and in them all

Fig. 3. If, for instance, we let perpendiculars to a horizontal line represent each one trial in the box, and let their heights represent in each trial the time it took the animal to escape (each three millimetres equaling ten seconds), the accompanying figure (Fig. 2) will tell the story of a cat which, when first put in, took sixty seconds to get out; in the second trial, eighty; in the third, fifty; in the fourth, sixty; in the fifth, fifty; in the sixth, forty, etc. This figure represents what did actually happen with one cat in learning a very easy act. Suppose the cat had, after the third accidental success, been able to reason. She would then have the next time and in all succeeding times performed the act as soon as put in, and the figure would have been such as we see in Fig. 3. The thing is still clearer if, instead of drawing in the perpendiculars, we draw only a line joining their tops. Fig. 4 shows, then, the curve for the real history, and Fig. 5 shows the abrupt descent, due to a rational comprehension of the situation. I kept an accurate record of the time, in seconds, taken in every trial by every cat in every box, and in them all  Fig. 4. there appears no evidence for the presence of even the little reasoning that "what let me out of this box three seconds ago will let me out now." Surely, if an animal could reason he would, after ten or eleven accidental successes, think what he had been doing, and at the eleventh or twelfth trial would at once perform the act. But no! The slope of the curves, as one may see in the specimens shown in Fig. 6, is always gradual. So, in saying that the behavior of the animals throughout the experiments gave no sign of the presence of reasoning I am not giving a personal opinion, but the impartial evidence of an unprejudiced watch. The curves given in Fig. 6 are for cats learning to escape from the box already described, whose door was held by a wooden button on the inside. Some one may object that, true as all this may be, the intelligent acts reported of animals are in many cases such as could not have happened in this way by accident. These anecdotes of apparent comprehension and inference are really the only argument which the believers in reason have presented. Its whole substance vanishes if, as a matter of fact, animals can do these supposed intelligent

Fig. 4. there appears no evidence for the presence of even the little reasoning that "what let me out of this box three seconds ago will let me out now." Surely, if an animal could reason he would, after ten or eleven accidental successes, think what he had been doing, and at the eleventh or twelfth trial would at once perform the act. But no! The slope of the curves, as one may see in the specimens shown in Fig. 6, is always gradual. So, in saying that the behavior of the animals throughout the experiments gave no sign of the presence of reasoning I am not giving a personal opinion, but the impartial evidence of an unprejudiced watch. The curves given in Fig. 6 are for cats learning to escape from the box already described, whose door was held by a wooden button on the inside. Some one may object that, true as all this may be, the intelligent acts reported of animals are in many cases such as could not have happened in this way by accident. These anecdotes of apparent comprehension and inference are really the only argument which the believers in reason have presented. Its whole substance vanishes if, as a matter of fact, animals can do these supposed intelligent  Fig. 5. acts in the course of instinctive struggling. They certainly can and do. I purposely chose, for experiments, two of the most intelligent performances described by Romanes in his Animal Intelligence—namely, the act of opening a door by depressing the thumb piece of an ordinary thumb-latch and the opening of a window by turning a swivel (see pp. 420-422 and p. 425 of Animal Intelligence, by G. J. Romanes). Here I may quote from the detailed report of my experiments (Monograph Supplement to the Psychological Review, No. 8):

Fig. 5. acts in the course of instinctive struggling. They certainly can and do. I purposely chose, for experiments, two of the most intelligent performances described by Romanes in his Animal Intelligence—namely, the act of opening a door by depressing the thumb piece of an ordinary thumb-latch and the opening of a window by turning a swivel (see pp. 420-422 and p. 425 of Animal Intelligence, by G. J. Romanes). Here I may quote from the detailed report of my experiments (Monograph Supplement to the Psychological Review, No. 8):

"G was a box 29 X 2012 X 2212, with a door 29 X 12 hinged on the left side of the box (looking from within), and kept closed by an ordiary thumb-latch placed fifteen inches from the floor. The remainder of the front of the box was closed in by wooden bars. The door was a wooden frame covered with screening. It was not arranged so as to open as soon as the latch was lifted, but required a force of four hundred grammes, even when applied to the best

Fig. 6.

advantage. The bar of the thumb-latch, moreover, would fall back into place again unless the door were pushed out at least a little. Eight cats (Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 13) were, one at a time, left in this thumb-latch box. All exhibited the customary instinctive clawings and squeezings and bitings. Out of the eight, all succeeded, in the course of their vigorous struggles, in pressing down the thumb-piece, so that if the door had been free to swing open they could have escaped. Six succeeded in pushing both thumb-piece down and door out, so that the bar did not fall back into its place. Of these, five succeeded in also later pushing the door open, so that they escaped and got the fish outside. Of these, three, after about fifty trials, associated the complicated movements required with the sight of the interior of the box so firmly that they attacked the thumb-latch the moment they were put in."

In the cases of No. 1 and No. 6 the combination of accidents required was enough to make their successes somewhat rare. Consequently weariness and failure offset the occasional pleasure of getting food, and after succeeding four and ten times respectively they never again succeeded, though given numerous opportunities. Their cases are almost a perfect proof of the claim that accident, not inference, makes animals open doors. For they hit upon the thing several times, but did not know enough to profit even by these experiences, and so failed to open the door the fifth and eleventh times.

Accident is equally capable of helping a cat escape from an inclosure whose door is held by a swivel.

"Out of six cats who were put in the box whose door opened by a button, not one failed, in the course of its impulsive activity, to push the button around. Sometimes it was clawed one side from below; sometimes vigorous pressure on the top turned it around; sometimes it was pushed up by the nose. No cat who was given repeated trials failed to form a perfect association between the sight of the interior of that box and the proper movements."

If, then, three cats out of eight can escape from a small box by accidentally operating a thumb-latch, one cat in a hundred may easily escape from a room by accident. If one hundred per cent of all cats are sure to sooner or later turn a button around when in a small box, one cat in a thousand may well escape from a room by accidentally turning a swivel around.

So far we have seen that when put in situations calculated to call forth any thinking powers which they possess, the animal's conduct still shows no signs of anything beyond the accidental formation of an association between the sight of the interior of the box and the impulse to a certain act, and the subsequent complete establishment of this association because of the power of pleasure to stamp in any process which leads to it. We have also seen that samples of the acts which have been supposed by advocates of the reason theory to require reasoning for their accomplishment turn out to be readily accomplished by the accidental success of instinctive impulses. The decision that animals do not possess the higher mental processes is re-enforced by several other lines of experiment—for example, by some experiments on imitation.

The details of these experiments I will not take the time to describe. Suffice it to say that cats and dogs were given a chance to see one of their fellows free himself from confinement and gain food by performing some simple act. In each case they were where they could see him do this from fifty to one hundred and fifty times, and did actually watch his actions closely from ten to forty times. After every ten chances to learn from seeing him, they were put into the same inclosure and observed carefully, in order to see whether they would, from having so often seen the act done, know enough to do it themselves, or at least to try to do it. In this they signally failed. Those who had failed previously to hit upon the thing accidentally never learned it later from seeing it done. Those who were given a chance to imitate acts which accident would sooner or later have taught them learned the acts no more quickly than if they had never seen the other animal do it the score or more of times. The animals, that is, could not master the simple inference that if, in a certain situation, that fellow-cat of mine performs a certain act and gets fish, I, in the same situation, may get fish by performing that act. They did not think enough to profit by the observation of their fellows, no matter how many chances for such observation were given them.

Equally corroborative of our first position are the results of still another set of experiments. Here the dogs and cats were put through the proper movement from twenty-five to one hundred times, being left in the box after every five or ten trials and watched to see if they would not be able at least to realize that the act which they had just been made to do and which had resulted in liberation and food was the proper act to be done. For instance, a dog would be put in a box the door of which would fall open when a loop of string hanging outside the box was clawed down an inch or so. Animals were taken who had, when left to themselves, failed to be led to this particular act by their general instinctive activities. After two minutes I would put in my arm, take the dog's paw, hold it out between the bars, and, inserting it in the loop, pull the loop down. The dog would of course then go out and eat the bit of meat. After repeating this ten times (in some cases five) I would put the dog in and leave him to his own devices. If, as was always the case, he failed in ten or twenty minutes to profit by my teaching I would take him out, but would not feed him. After a half hour or so I would recommence my attempts to show the dog what needed to be done. This would be kept up for two or three days, until he had shown his utter inability to get the notion of doing for himself what he had been made to do a hundred or more times. The mental process required here need not be so high a one as inference or reasoning, but surely any animal possessing those would, after seeing and feeling his paw pull a loop down a hundred times with such good results, have known enough to do it himself. None of my animals did know enough. Those who did not in ten or twelve trials hit upon an act by accident could never be taught that act by being put through it. And, as in the case of imitation, acts of such a sort as would be surely learned by virtue of accidental success were not learned a whit sooner or more easily when I thus showed them to the animal.

An interesting supplement to these facts is found in the following answers to some questions which I sent to the trainer of one of the most remarkable trick-performing horses now exhibited on the stage. The counting tricks done by this horse had been quoted to me by a friend as impossible of explanation unless the horse could be educated by being put through the right number of movements in connection with the different signals.

Question 1.—If you wished to teach a horse to tap seven times with his hoof when you asked him "How many days are there in a week?" would you teach him by taking his leg and making him go through the motions?

Answer.—"No!"

Question 2.—Do you think you could teach, him that way, even if naturally you would take some other way?

Answer.—"I do not think I could."

Question 3.—How would you teach him?

Answer.—"You put figure 2 on the blackboard and touch him on the leg twice with a cane, and so on."

The counting tricks of trained horses seem to us marvelous because we are not acquainted with the simple but important fact that a horse instinctively raises his hoof when one pricks or taps his leg in a certain place. Just as once given, the cat's instinct to claw, squeeze, etc., you can readily get a cat to open doors by working latches or turning buttons, so, once given this simple reflex of raising the hoof, you can, by ingenuity and patience, get a horse to do almost any number of counting tricks.

Probably any one who still feels confident that animals reason will not be shaken by any further evidence. Still, it will pay any one who cares to make scientific his notions about animal consciousness to notice the results of two sets of experiments not yet mentioned. The first set was concerned with the way animals learn to perform a compound act. Boxes were arranged so that two or three different things had to be done before the door would fall open. For instance, in one case the cat or dog had to step on a platform, reach up between the bars over the top of the box and claw down a string running across them, and finally push its paw out beside the door to claw down a bar which held it.

The animal's instinctive impulses do often lead it to accidentally perform these several acts one after another, and repeated accidental successes do in some of these cases cause the acts to be done at last in fairly quick succession. But we see clearly that the acts are not thought about or done with anything like a rational comprehension of the situation, for the time taken to learn the thing is much longer than all three elements would take if tackled separately; and even after the animal has reached a minimum time in doing the acts, he does not do the things in the same order, and often repeats one of the acts over and over again, though it has already attained its end.

The second set comprised experiments on the so-called "memory" of animals. I will describe only one out of many which agree with it, A kitten had been trained to the habit of climbing the wire-netting front of its cage whenever I approached. I then trained her to climb up at the words "I must feed those cats." This was done by uttering them and then in ten seconds going up to the cage and holding a bit of fish to her at its top. After this had been done about forty times she reached a point where she would climb up at the signal about fifty per cent of the times. I then introduced a new element by sometimes saying, "I must feed those cats," as before, and feeding her, and at other times saying, "I will not feed them," and remaining still in my chair. At first the kitten felt no difference, and would climb up just as often at the wrong signal as at the right. But gradually (it took about four hundred and fifty trials) the failure to get any pleasure from the act of climbing up at the wrong signal stamped out the impulse to do so, while the pleasure sequent upon the act of climbing up at the other signal made that her invariable response to it. Here, as elsewhere, the absence of reason was shown by the cat's failure at any point in these hundreds of trials to think about the matter, and make the easy inference that one set of sounds meant food, while the other did not. But still better proof appears in what is to follow. After an interval of eighty days I tried her again to see how permanent the association between the signal and act was. It was permanent to the extent that what took three hundred and eighty trials before took only fifty this time, for after fifty trials with the "I will not feed them" signal, mixed up with a lot of the other, the cat once more attained perfect discrimination. But it was not permanent in the sense that the cat at the first or tenth or twentieth trial felt, as a remembering, reasoning consciousness surely ought to feel, "Why, that lot of sounds means that he won't come up with fish." For instead of at first forgetting and for a while climbing up at the I will not feed them, and then remembering its previous experience and at once stopping the performance it had before learned was useless, the cat simply went through the same gradual decreasing of the percentage of wrong responses until finally it always responded rightly.

What has so far been said is true regardless of any prejudice or incompetence on my part, for the proof in all cases rests not on my observation, but on impartial time records or such matters of fact as the escape or nonescape, the climbing or not-climbing of the animals. I may add that in a life among these animals of six months for from four to eight hours a day I never saw any acts which even seemed to show reasoning powers, and did see numerous acts unmentioned here which pointed clearly to their absence.

All that is left for the fond owner of a supposedly rational animal to say is that though the average animal, the typical dog or cat, is by these experiments shown to be devoid of reasoning power, yet his dog or her cat is far above the average level, and is therefore to be judged by itself. He may claim that just because my average animals failed to infer, we have no right to deny inference to all, particularly to his. Is it not fair to ask such a one to repeat my experiments with his supposedly superior animal? Until he does and systematically tries to find out how its mind works and what it is capable of, has he any right to bear witness? It may also be said that of the number of people who witnessed the performances of my animals after they had fully learned a lot of these acts, but had not seen the method of acquisition, all unanimously wondered at their wonderful intellectual powers. "How do you teach them?" "Where did you get such bright animals?" "I always thought animals could think," and such like were common expressions of my visitors. The fact was that the dogs and cats were picked up in the street at random, and that no one of them had thought out one jot or tittle of the things he had learned to do. The specious appearance of reasoning in a completely formed habit does not involve the presence or assistance of reasoning in the formation of the habit.

Here, at the close of this account, I may signify my willingness to reply, so far as is possible, to any letters from readers of the Popular Science Monthly who may care to ask questions about any feature of animal intelligence.