Popular Science Monthly/Volume 55/August 1899/Some Practical Phases of Mental Fatigue

will be the resultant of any given present impression modified by others previously received and treasured up in memory, as we say. To accomplish this really great feat, Nature had to devise an elaborate contrivance, interposed between incoming messages and outgoing impulses, to act as a moderator or transformer of a very extraordinary and intricate character—the central nervous system, comprising the brain and spinal cord. That it may be able to meet the requirements of its office, this system must be equipped with two principal kinds of apparatus—cells, which will serve as storehouses of energy to be employed in keeping the machinery running, and association fibers or pathways, which will put any one cell into communication with others in the cerebral community.

The item which will engage our attention principally here relates to the primary function of the nerve cell—to store up vital forces in the form of highly unstable chemical compounds,[1] which may upon slight disturbance be broken down, the static energy represented in their union thus becoming dynamic. Those who have given special attention to the matter seem to agree that all activity, physical as well as mental, involves the expenditure of a portion of this energy.[2] It may perhaps be mentioned in passing that when this conception was first being presented some persons hastily constructed the theory that what people had been calling mind was nothing more nor less than a certain mode of manifestation of this mysterious but yet physical force. While abundant evidence, gained from various sciences by recent research, leads one to the conviction that in some unknown manner psychical and neural processes are closely co-ordinated, yet not a single investigator of standing claims that they are identical. There is doubtless among some in our day too great a tendency, unconscious though it may be for the most part, to declare that a description of the physical correlates or antecedents of mental phenomena fully accounts for the latter in respect alike of their nature and their modes of manifestation; but those who find themselves coming to such conclusions might be both interested in and benefited by examining the opinions of great naturalists and psychologists who have reflected long and profoundly upon the world-old problem of the connections between body and mind—such men as Lotze,[3] Darwin,[4] Romanes,[5] Wallace,[6] Fiske,[7] Drummond,[8] Wundt,[9] and many others of equal scientific attainments.

The architecture and chemical constitution of the neural elements indicate unmistakably, it seems, that they were so constructed that in their functioning they would be amenable to the law of the conservation of energy, and recent investigations have produced some experimental evidence in support of this view. Hodge,[10] who succeeded in making microscopical examinations of living nerve cells while under stimulation, demonstrated that the cell by this treatment was depleted of its contents, as revealed in the gradual reduction of its size. In corroboration of these results it was found that the cerebral cells in animals were larger in the morning than after a day's activities, indicating that depletion must have taken place during waking life, followed by recuperation in sleep. Some interesting data relating in a way to this matter are easily gained in the laboratories by the use of the plethysmograph, which is designed to record the degree of blood pressure in different parts of the body. This instrument may be put upon the wrists and head, for instance, and it may be observed, when a person is subjected to certain influences whether, there is any alteration in blood supply in either region. It may be noticed, as a matter of fact, that when one is required to think diligently upon any problem, or being asleep is awakened or even disturbed by a noise in his environment, the volume of blood decreases in the wrist and increases in the head.[11] This same phenomenon is shown by experiments with the scientific cradle.[12] The inference from these data seems reasonable, that mental activity causes an expenditure of nerve force, which Nature seeks to replenish by inciting an unusual flow of nutritive-bearing fluid to the cerebral cortex. It has been shown, in further illustration of this law, that thought increases the temperature of the head, indicating that heat is generated through molecular activity; and also that psychical action increases waste products in the system, which may be derived only from the degradation of substances in nerve cells.[13] So information obtained from various other sources points toward the conclusion that in all activity energy stored in nerve cells is dissipated.

Recent experimental studies have given us reasons for believing that nerve cells in different individuals yield up their energy in response to stimulation with varying degrees of readiness.[14] Experience corroborates what Professor Bryan[15] has said: that some persons possess a leaky nervous system, wherefrom their vitalities flow away without issue in useful results. In such individuals activity will be likely to be in excess of that which the stimulus occasioning it should normally produce. Every one must have seen children, and adults as well, who when they hear a slight noise, for instance, which others do not mind, react with great vigor by jumping or screaming; or, when spoken to unexpectedly the face flushes, the lip quivers, and they become physically uncontrolled in a measure. In these instances the persons are unduly profligate in the expenditure of their means, and, in consequence, their capital is relatively soon exhausted.[16]

The writer last year conducted some experiments upon school children which yielded results that appear to confirm the view here set forth. Scripture's steadiness gauge was used in one test. This is designed to investigate stability of control by requiring a person to direct a light rod under guidance of the eye upon a point several feet distant, failure to accomplish this being announced by the ringing of an electric bell. The subject is usually required to make the trial fifteen times at a single test, and the number of successful attempts is taken to be in a way, although not always reliable, an index to his power of co-ordination. But more important than the success or failure in accomplishing the task is the index it affords of the nervous condition of the subject as revealed in the expressions of face and body. Tests were made in the morning, shortly following the opening of school, and again at half past eleven o'clock, or thereabouts, after the pupils had been working over their lessons for about two hours. One boy of eleven years, A. M., is a fair illustration of what might not inappropriately be called an exhaustive type, wherein nervous energy is readily depleted because of incessant waste. In the morning tests he was well controlled and accurate. A record of five tests made at half past eleven all show that after four or five attempts to place the rod upon the point the hand became very unsteady, the lips compressed, the region about the eyes showed unusual constraint, and the hand not being used was tightly clinched. Ten trials were usually sufficient to produce twitchings or tics in the face and body, although nothing of this was ever noticed at other times. This boy invariably made hard work of the task, and all the physical accompaniments indicated excessive motor stimulation following, of course, upon an unduly excited condition of the cerebral cells. At the close of the experiments he generally seemed exhausted, and upon three occasions it was thought best not to permit him to make the entire fifteen trials.

Another pupil, W. R., two years younger, illustrates a different type. In the morning trials he was no better than A. M., but he, too, was subjected to five different tests at half past eleven, with the result that he could in every instance complete the task without any apparent fatigue. There was no constraint apparent in the face or hands, no unusual effort to co-ordinate the muscles of the body, and no twitchings of any kind. Now, it seems probable that in the case of W. R. the brain was able to adjust effort in right degree to the needs of the occasion, while with A. M. there was such prodigality in the expenditure of energy in various irrelevant motor tensions and activities that it not only defeated its purpose, but it was soon largely spent. A. M. showed this tendency to nervous extravagance in all the work of the school. While an unusually bright boy, he yet became fatigued in the performance of duties that W. R. could discharge with no evidence of overstrain; indeed, the latter boy seemed never to reach a point beyond which he could not go with safety if he chose.

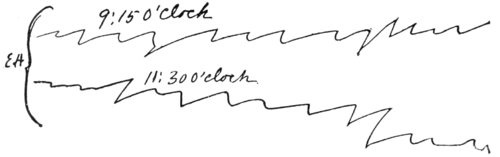

Further illustrations of this principle of individual differences in the conservation of nervous energy were afforded by another simple experiment. The apparatus employed consisted of a plate of smoked glass set in a frame so that it could be moved horizontally. Just touching the glass, and adjusted to it by a delicate spring, was a fine metal point which could be maintained at any height by a silk thread to be held in the fingers of the subject to be experimented upon, who stood with closed eyes endeavoring to keep his hand perfectly quiet for one half minute. During the test the glass was moved slowly in the frame, the metal point thus tracing a line which was a faithful index to most of the movements, at any rate, of the subject's hand. Five sets of experiments were made upon a number of pupils in the morning soon after the opening of school, and again just before the noon recess. The accompanying tracings are reproductions of those gained at one of the tests, and are typical examples. The first two were secured from a girl, M. L. R., eleven years of age. The one made at half past eleven, after two and a quarter hours' work in school, shows a significant phenomenon which could be easily witnessed during the experiment. She had become so fatigued that all muscular expressions were unusually constrained. During the short period while the experiment continued one could observe the arm and fingers contracting, which accounts for the upward direction of the. tracing. The body swayed almost to the point of falling, the fingers of the hand not employed were clinched, and all the expressions indicated great tension. The second set of tracings, gained from a girl, E. H., twelve years of age, shows evidences of marked fatigue after a few hours' work; but the effect upon the bodily activities is quite in contrast with that of the case just mentioned. Here there was relaxation of the muscles,

a general letting go of the whole body, revealed in the tracings taking an abrupt downward direction. The third group of tracings was gained from W. R., whose characteristics have already been adverted to, and who indicated here, as in the other tests, that his morning's duties had had no serious effect upon his nervous energies.

It should be said in passing that the principle of healthful mental growth and activity seems to require that in education of any sort cerebral cells should be freely exercised up to the point of fatigue, but never beyond; for after this there is not only no progress, but what has been gained by previous training may even be lost. And, what is more serious, the undue depletion of the nerve cell renders

its recovery extremely slow, and investigation has shown that school children when overtaxed return to their studies day after day in a fatigued condition, their energies not being fully restored until the long vacation brings the needed rest.[17] Those who train athletes realize that the fatigue limit must not be passed if possible, and this law is recognized as well in the training of racing horses.[18] One who has observed his experience in learning to ride the bicycle must have discovered that practice pursued when in a condition of exhaustion operates rather to retard than to promote facility. So in matters of the mind activity carried to excess, which point is further removed in some cases than in others, results in retardation of growth, even though no more serious consequences ensue.

II.

As might be readily inferred, even if we were lacking xperimental evidence, fatigue interferes with the normal activities alike of body and mind. One of the earliest and most conspicuous effects may be observed by any one in the people about him—a decrease in the rapidity of physical action. The child depleted of nervous energy, for whatever reason, will usually be slower than his fellows in performing the various activities of home or school. If observed during gymnastic exercises it may be noticed that his execution of the various commands is delayed; in responding to signals he is behind his comrades whose nervous capital is not so largely spent. And what is here said of the child is, of course, equally true in principle of the adult; the effect of fatigue in his case will be revealed in less lively, vivacious, and vigorous conduct in the affairs of business or of society. Mosso,[19] Burgerstein,[20] Scripture,[21] Bryan,[22] and others have been able to confirm by scientific experiment what people have thus long been conscious of in a way—that cerebral fatigue renders one slower, more lethargic in his activities. It seems clear, to hazard an explanation, that when nerve cells become depleted up to the point of fatigue Nature designs that they should be released from service in order that repair may take place. This rhythm of action and repose seems to be common to all forms of life. The phenomenon of sleep is an expression of this principle, and is characterized by almost entire absence of activity.

Again, fatigue disturbs the power of accurate and sustained bodily co-ordinations, particularly of the peripheral muscles, or those engaged in the control of the more delicate movements of the body, as of the fingers. Every one must have had the experience that consequent upon a period of exacting labor (physical or mental), or worry, the hand becomes unsteady, as revealed in writing or other fine work, the voice is not so perfectly controlled as at other times, and perhaps involuntary twitchings or tics make their appearance in the face or elsewhere. Ordinarily people regard these phenomena as evidences simply of "nervousness," but, as commonly used, this term does not take account of the neural conditions responsible for these abnormal manifestations. Warner[23] points out that nerve cells in a state of fatigue become impulsive or spasmodic in their action; there is not such perfect balance as usually exists between them when in a normal, rested condition, and this results in lessened power of inhibition. Scripture[24] and others have shown by experiments in the laboratory that fatigue renders co-ordination less sustained and accurate. If, now, one observes a group of people, young or old, in which some or all have passed the fatigue limit, he can see the cause of many of those occurrences which give the teacher in the school, for example, continual trouble. The children will doubtless be moving incessantly in their seats, books and pencils may be dropping upon the floor, and various signals are responded to slowly and in a disorderly manner. The restlessness is probably due for the most part to the effort of the pupils to relieve the tension of muscles induced by overstrain, while inability to accurately co-ordinate the muscles employed in holding pencils and books causes objects to slip out of the pupils' hands upon the floor. One has but to observe his own experience, and he will soon realize that when nervously exhausted he is not so certain of retaining securely small objects which he handles. This accounts for what is sometimes regarded as carelessness in school children as well as in adults, exhibited in slovenly writing, in breaking dishes, and in similar occurrences. Any task demanding delicate and sustained adjustment of the finer muscles on the part of one fatigued will be liable to be performed in a careless manner, as we are apt to feel. Often more than not the term carelessness probably denotes impaired neural conditions, as well as consequent mental dispersion, if one may so speak, leading to inaccurate and intermittent mental and physical adjustments to duties in hand.

Cowles[25] observes that the first prominent and serious mental concomitant of nervous depletion is revealed in the inability to direct the attention continuously upon any given subject; and James has said that when one is fatigued the mind wanders in various directions, snatching at everything which promises relief from the object of immediate attention. Experiments in the laboratory upon the keenness of sense discrimination of data appealing to sight, hearing, touch, and the other senses, show that there is lessened ability in conditions of fatigue;[26] and this is accounted for probably by the waning power of attention. The mind can be held to one thing, excluding irrelevant matters. This phenomenon is further illustrated in the following simple experiment: The pupils in a large graded school in Buffalo, N. Y., were required upon three successive days, at half past nine o'clock and again at half past eleven in the morning, to trisect a line three inches long. The results, calculated for one hundred and fifty children, show that on the average they were several millimetres nearer correct in the morning trisections than in those just before the midday recess.[27] It seems that this test measured the degree of attention which pupils were able to exert at different hours during the day, and it confirmed what must in a way be known to every one—that a day's work in school reduces the energy of attention. Doubtless every instructor has remarked how much more difficult it is at half past eleven than at ten to hold the thoughts of students to the subject in hand, and if recitations in intricate studies occur late in the forenoon, progress will be slower and more errors will be made, simply because pupils are unable to attend so critically.

The significance of this latter effect of fatigue must be apparent when it is realized that attention is at the basis of all the intellectual processes. If one can not attend vitally, he can not perceive readily or accurately; he will be unable to recall fully or speedily what has formerly been thoroughly mastered; and, most serious of all, he can not so well compare objects or ideas to discover their relationships—that is, he is not so ready or accurate in reason. In fatigue, then, one really becomes stupid. Suppose a fatigued pupil in school working over his spelling lesson, for instance; he will be liable to make errors both in copying from the board and in reproducing what he already knows. In recitations in history, memory will be halting; what has apparently been made secure some time before now seems to be out of reach. In those studies requiring reflection, as arithmetic, grammar, geography, and the like, the reasoner will be unable to hold his thoughts continuously to the matters under consideration, and so will be unable to detect relationships between them readily and accurately. When one considers, in view of what is here set forth, that many persons, adults as well as students, are for one cause or another in a constant state of fatigue, he can see the explanation of the stupid type of individual, in some instances at any rate.

The effects upon the emotional activities, while not so easily detected by experimentation, may yet be readily observed in one's own experiences and in the conduct of persons in his environment. Cowles,[28] Beard,[29] and others assure us as physicians that neurasthenia gives rise to irritability, gloominess, despondency, and sets free a brood of fears and other kindred more or less abnormal feelings. Wey,[30] in his studies upon the physical condition of young criminals, has found that in the majority of instances there appears to be some neural defect or deficiency, mostly of the nature of depletion, which he believes contributes to alienate the moral feelings of the individual. There is little doubt that viciousness has a physiological basis. It is probable that in such a case the highest cerebral regions, through which are transmitted the spiritual activities last developed in the race, becoming incapacitated first by fatigue, are rendered incapable of inhibiting impulses from the lower regions, which manifest themselves in an antisocial way.

III.

It follows from what has gone before that cerebral fatigue is a most important matter to be reckoned with in all the affairs of life, but especially in education, where the foundations for nervous vigor or weakness are being permanently established, and where relatively little can be accomplished in either intellectual or moral training unless the physical instrument of mind be kept in good repair. It needs no argument to beget the conviction that we should if possible ascertain what circumstances produce fatigue most frequently in the schoolroom, so that they may be ameliorated and their injurious consequences thus avoided. What, then, are the most important causes? It is well to appreciate at the outset that every individual has a certain amount of nervous capital which, when expended, leaves him a bankrupt, and it is of supreme import to him that something should always be kept on the credit side of his account. If we would deal most wisely with a pupil, then, whose activities we are able to direct, we should know just what demands we could make upon his energies without fatiguing him. But we can not hope at the present time and under present conditions to discover with accuracy the fatigue point of each individual, and even if we were able to do so, we would doubtless find it next to impossible to observe it at all times in our teaching, especially in our large graded schools. But we can at any rate adjust our requirements with some degree of accuracy to the average capacity of the whole.

Regarding the number of hours of mental application per day which may be safely expected of a pupil in school, investigations have tended to show that there is a danger of requiring too many. When pupils return to school morning after morning without having recovered from the previous day's labors, it is evident that too heavy draughts are being made upon their nervous capital. It may be said in reply that many factors conspire to produce this depleted condition, as insufficient sleep, inadequate nutrition, and outside duties; but the answer is that under such unfavorable circumstances less work may be demanded. As the curriculum is planned in many places, alike in graded and ungraded schools, the pupil is expected to be employed in the school for five or six hours a day no matter what may be his age, and to this work should be added studies at home for the older students. Now, as Kraeplin[31] has justly observed. Nature ordains that a young child should not give six hours' daily concentrated attention in the schoolroom, but, rather, she has taken pains to implant deeply within him a profound instinct to preserve his mental health by refusing to attend to hard work for such a long period. Consequently, in such an educational regime, the mind of the pupil continually wanders from the duties in hand. The most serious aspect of this is apparent, that when attention is constantly demanded and not given, or when a pupil is pretending or attempting to keep his thoughts turned in a given direction, yet allows them to drift aimlessly because he is practically unable to control them, he is acquiring an unfortunate habit of mental dissipation. It seems certain that healthful and efficient mental activity requires that a child apply himself in a maximum degree for a relatively short period, the duration differing with the age of the individual and the balance of nervous energy to his credit; and then he should relax, attention being released for a time.

Experiments conducted by Burgerstein[32] and at Leland Stanford Junior University[33] emphasize a particular phase of this principle—that too long continued mental application without relaxation induces fatigue more readily than when there are comparatively short periods of effort, followed by intermissions of rest. Thus when pupils (and the younger they are the more is this true) have a given amount of work to do requiring their attention say for an hour and a half they will accomplish most with least waste of energy by breaking up this long stretch into several parts, interspersing a few minutes of free play. With adults application may profitably continue for longer periods, but even here the rhythm of concentration and relaxation must be observed in order that effort may have the most fruitful issue. There would assuredly be less dullness, carelessness, and disorder in our schools, high and low, and in our homes, if this law were observed in the arrangement of the activities of daily life. The writer knows of a normal school where the work begins at half past eight in the morning and continues until one o'clock, with a pause of only ten minutes in the middle of the session. During the passage of classes from room to room at the close of recitations, monitors are placed in the halls to prevent any exhibition of freedom in communicating with one another or in the movements of the body. Here there is little if any relief to the attention, since pupils are under practically the same constraint as when reciting in Latin, Greek, or geometry. This enthronement of discipline, which we all seem natively to think necessary that we may prevent the reversionary tendencies of youth, is sure to breed in some measure the very maladies—stupidity and disorder—which various agencies in society are striving to cure by all sorts of formulæ.

In the normal, well-organized adult brain the various areas are closely knit together by association pathways or fibers,[34] which renders it possible to employ in particular direction the energies generated over large regions. But this development comes relatively late and is not fully completed under about thirty-three years of age, it is now believed. It is in a measure, then, impossible for the young child to utilize the energies produced in one part of the brain in activities involving remote sections. One who observes little children in their spontaneous activities can not fail to note evidences in plenty in illustration of this principle. It should be apparent, then, why a school programme so arranged that a lesson in writing is followed by one in written language, this by written number, and this in turn by written spelling, or possibly by a written reproduction of a lesson in Nature or literature, is admirably suited to exhaust the overused areas of pupils' brains, whereupon the mental and physical effects of fatigue make their appearance. In one of the large cities of our country the amount of time spent in writing was calculated for all the grades in the schools, and it was found that at least one hour was required of the children in every grade, and in the fourth and fifth grades they were engaged for two hundred minutes every day in writing in some form or other.

Doubtless every one has observed how readily he becomes fatigued when he is engaged in activities demanding very delicate muscular adjustments—threading a needle, for instance. Work of this character involves particularly the higher co-ordinating areas of the brain, those controlling the more precise and elaborate adjustments of the body, and this work makes large demands upon one's nervous energy. This seems to be pre-eminently true of the child, in whose brain the highest regions are yet comparatively undeveloped, so that much exercise of them leads quickly to exhaustion. Those activities, then, which compel a great amount of exact co-ordination of young children will easily fatigue them. The writer has for some time been observing the effect of various sorts of playthings upon the activities, particularly upon the emotions, of two young children. He has noticed that those plays requiring most accurate co-ordination, as stringing kindergarten beads with small openings or writing with a hard lead pencil, will quickly produce fatigue, shown in irritability, discontent, and lack of control; while those plays which employ the larger muscles, as working in sand or drawing a cart, are more enduring in their interest and are not attended by such disagreeable after effects. It is customary, however, in many homes and schools to require of the youngest children the finest work in the management of the smallest tools and materials, such, for instance, as writing on very narrow spaced paper, greater freedom being permitted in this respect as the pupil grows older—an inversion of the natural order. The mode of development of the nervous system indicates unmistakably that in all training the individual should proceed gradually from the acquirement of strength and force in large, coarse, and relatively inexact movements to the acquisition of skill in precisely co-ordinated activities.

Any reference to the remediable casues of mental fatigue would be incomplete without allusion to the harmful influence of certain personal characteristics in the people with whom we associate. By virtue of a great law of our being, that of suggestion, the importance of which we are appreciating more fully from day to day, we tend ever to reproduce within ourselves the activities of the things in our environment.[35] Now, when we are forced to remain in the presence of one fatigued, as pupils too frequently are in the school and children in the home, and this fatigue manifests itself in irritability, impatience, tension of voice, and constraint of face and body—in such an environment we become overstimulated ourselves and rapidly waste our energies. Especially true is this of children, who are more suggestible than adults; and, in view of this, one can appreciate the necessity of placing in our schoolrooms, and if we could in our homes, persons possessing an endowment of nervous energy adequate for the demands to be made upon it without inducing too readily fatigue with all its train of evils.

- ↑ For chemical formulæ of some of the compounds, see Ladd, Outlines of Physiological Psychology, p. 13.

- ↑ For the opinions of investigators, as Mosso, Lombard, Maggiora, Kraeplin, and others, see Pedagogical Seminary, vol. ii. No. 1, pp. 13-17; Scripture, The New Psychology, chapter xvi; and Educational Review, vol. xv, pp. 246 et seq.

- ↑ Microcosmus, p. 162.

- ↑ Descent of Man, p. 66.

- ↑ Mental Evolution in Man, pp. 213 et seq.

- ↑ Darwinism, p. 469.

- ↑ Destiny of Man in the Light of his Origin.

- ↑ Ascent of Man.

- ↑ Human and Animal Psychology, pp. 5-7 and 440-445.

- ↑ For a complete statement of methods and results, see Hodge, American Journal of Psychology, vol. ii, pp. 3 et seq.; and vol iii, pp. 530 et seq.

- ↑ See Pedagogical Seminary, vol. ii, pp. 12 et seq.

- ↑ Ibid., op. cit.

- ↑ Cowles, Neurasthenia and its Mental Symptoms, pp. 17 et seq.

- ↑ Educational Review, op. cit.

- ↑ Addresses and Proceedings of the National Educational Association, 1897, p. 279.

- ↑ Cf. Warner, The Study of Children, chapters viii and ix.

- ↑ Educational Review, op. cit.

- ↑ Bryan, Addresses and Proceedings of the National Educational Association, 1897.

- ↑ Pedagogical Seminary, vol. ii, pp. 20 et seq.

- ↑ Ibid., op. cit.

- ↑ The New Psychology, pp. 128-132.

- ↑ The Development of Voluntary Motor Ability, p. 76.

- ↑ Mental Faculty, pp. 76, 77.

- ↑ The New Psychology, pp. 236-248.

- ↑ Op. cit., p. 47.

- ↑ See Educational Review, op. cit.; Galton, Journal of the Anthropological Institute, 1888, pp. 153 et seq.

- ↑ Since this article was written extensive investigations on school-room fatigue have been made in the schools of Madison, Wis., under the writer's direction, and the general principles here mentioned have been corroborated.

- ↑ Op. cit., pp. 47 et seq.

- ↑ Papers in Penology, 1891, pp. 57-60; cf. Collin, also in same, pp. 27, 28; Wright, American Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry, vols, ii and iii, pp. 135 et seq.

- ↑ Op. cit., pp. 36-117.

- ↑ A Measure of Mental Capacity, Popular Science Monthly, vol. xlix, p. 758.

- ↑ Op. cit.

- ↑ Pedagogical Seminary, vol. iii, pp. 213 et seq.

- ↑ Donaldson, The Growth of the Brain, chapters ix to xiii.

- ↑ Cf. Sidis, The Psychology of Suggestion; and Vernon Lee and C. A. Thompson, Beauty and Ugliness, Contemporary Review, vol. lxxii, pp. 544-569 and 669-688.