Rude Stone Monuments in All Countries/Chapter 2

CHAPTER II.

PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS.

Before attempting to examine or describe particular instances—in which, however, the main interest of the work must eventually be centred—it would add very much to the clearness of what follows if a classification could be hit upon, which would correctly represent the sequence of forms. In the present state of our knowledge such an arrangement is hardly possible, still the following 5 groups, with their subdivisions, are sufficiently distinct to enable them to be treated separately, and are so arranged as roughly to represent what we know of their sequence, with immense overlappings, however, on every joint.

| I.—Tumuli | .. | .. | a. Or barrows of earth only. |

| b. With small stone chambers or cists. | |||

| c. With megalithic chambers or dolmens. | |||

| d. With external access to chambers. | |||

| II.—Dolmens | .. | .. | a. Free standing dolmens without tumuli. |

| b. Dolmens upon the outside of tumuli. | |||

| III.—Circles | .. | .. | a. Circles surrounding tumuli. |

| b. Circles surrounding dolmens. | |||

| c. Circles without tumuli or dolmens. | |||

| IV.—Avenues | .. | .. | a. Avenues attached to circles. |

| b. Avenues with or without circles or dolmens. | |||

| V.—Menhirs | .. | .. | a. Single or in groups. |

| b. With oghams, sculptures, or runes. |

Tumuli.

The first three of the sub-divisions of the first class are so mixed together that it is almost impossible in the present state of our knowledge to separate them with precision either as to date or locality, while, as they hardly belong to the main subject of this book, it will not be worth while to attempt it here.

Without being too speculative, perhaps, it may be assumed that the earliest mode in which mankind disposed of the bodies of their deceased relatives or neighbours was by simple inhumation. They dug a hole in the earth, and, having laid the body therein, simply replaced the earth upon it, and to mark the spot, if the person so buried was of sufficient importance to merit such care, they raised a mound over the grave. It is difficult, however, to believe that mankind were long content with so simple a mode of sepulture. To heap earth or stones on the body of the beloved departed so as to crush and deface it, must have seemed rude and harsh, and some sort of coffin was probably early devised for the protection of the corpse,—in well-wooded countries, this would be of wood, which, if the mound is old, has perished long ago—in stony countries, as probably of stone, forming the rude cists so commonly found in early graves. That these should expand into chambers seems also natural as civilization advanced, and as man's ideas of a future state and the wants and necessities of such a future became more developed.

The last stage would seem to be when access was retained to the sepulchral chamber, in order that the descendants of the deceased might bring offerings, or supply the wants of their relative during the intermediate state which some nations assumed must elapse before the translation of the body to another world.

It is probable that some such stages as these were passed through by all the burying races of mankind, though at very various intervals and with very different details, while fortunately for our present subject it seems that the earliest races were those most addicted to this mode of honouring their dead. All mankind, it is true, bury their dead either in the flesh or their ashes after cremation. It is one of those peculiarities which, like speech, distinguish mankind from the lower animals, and which are so strangely overlooked by the advocates of the fashionable theory of our ape descent. All mankind, however, do not reverence their dead to the same extent. The peculiarity is most characteristic of the earlier underlying races, whom we have generally been in the habit of designating as the Turanian races of mankind. But if that term is objected to, the tomb-building races may be specified—beginning from the East—as the Chinese; the Monguls in Tartary, or Mogols, as they were called, in India; the Tartars in their own country, or in Persia; the ancient Pelasgi in Greece; the Etrurians in Italy; and the races, whoever they were, who preceded the Celts in Europe. But the tomb-building people, par excellence, in the old world were the Egyptians. Not only were the funereal rites the most important element in the religious life of the people, but they began at an age earlier than the history or tradition of any other nation carries us back to. The great Pyramid of Gizeh was erected certainly as early as 3000 years before Christ; yet it must be the lineal descendant of a rude-chambered tumulus or cairn, with external access to the chambers, and it seems difficult to calculate how many thousands of years it must have required before such rude sepulchres as those our ancestors erected—many probably after the Christian era—could have been elaborated into the most perfect and most gigantic specimens of masonry which the world has yet seen. The phenomenon of anything so perfect as the Pyramids starting up at once, absolutely without any previous examples being known, is so unique[1] in the world's history, that it is impossible to form any conjecture how long before this period the Egyptians tried to protect their bodies from decay during the probationary 3000 years.[2]

Outside Egypt the oldest tumulus we know of, with an absolutely authentic date, is that which Alyattes, the father of Crœsus,

king of Lydia, erected for his own resting-place before the year 561 B.C. It was described by Herodotus,[3] and has of late years been thoroughly explored by Dr. Olfers.[4] Its dimensions are very considerable, and very nearly those given by the father of history. It is 1180 feet in diameter, or about twice as much as Silbury Hill, and 200 feet in height, as against 130 of that boasted monument. The upper part, like many of our own mounds, is composed of alternate layers of clay, loam, and a kind of rubble concrete. These support a mass of brickwork, surmounted by a platform of masonry; on this still lies one of Steles, described by Herodotus, and another of the smaller ones was found close by.

There is another group of tombs, called those of Tantalais, found near Smyrna, which are considerably older than those of Sardis, though their date cannot be fixed with such certainty as that last described. Still there seems no good reason for doubting that the one here represented may be as old as the eleventh or twelfth century B.C., nor does it seem reasonable to doubt but these tumuli which still stand on the plain of Troy do cover the remains of the heroes who perished in that remarkable siege.[5]

A still more interesting group, however, is that at Mycenæ, known as the tombs or treasuries of the Atridæ, and described as such by Pausanias.[6] The principal, or at least the best preserved of these, is a circular chamber, 48 feet 6 inches in diameter, covered by a

horizontal vault, and having a sepulchral chamber on one side. Dodwell discovered three others of the five mentioned by Pausanias,[7] and he also explored the sepulchre of Minyas at Orchomenos, which had a diameter of 65 feet.

Another group of tombs, contemporary or nearly so with these, are found in the older cemeteries of the Etrurians at Cœre, Vulci, and elsewhere. One of the largest of these is one called Cocumella, at Vulci, which is 240 feet in diameter, and must originally

have been 115 to 120 feet in height. Near the centre rise two steles, but so unsymmetrically that it is impossible to understand why they were so placed and how they could have been grouped into anything like a complete design. The sepulchre, too, is placed on one side.

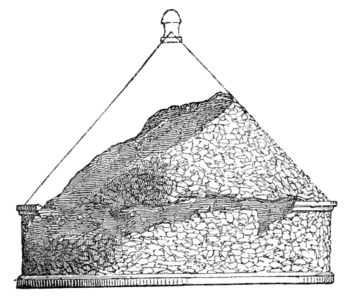

A still richer and more remarkable tomb is that known as the Regulini Galeassi Tomb at Cœre, the chamber of which is represented in the annexed woodcut.

It is filled, as may be seen, with vessels and furniture, principally of bronze and of the most elaborate workmanship. The patterns on these vessels are so archaic, and resemble so much some of the older ones found at Nineveh, whose dates are at least approximately known, that we may safely refer the tomb to an age not later than the tenth century B.C.[8]

We have thus around the eastern shores of the Mediterranean a group of circular sepulchral tumuli of well defined age. Some, certainly, are as old as the thirteenth century B.C., others extend downwards to, say 500 B.C. All have a podium of stone. Some are wholly of that material, but in most of them the cone is composed of earth, and all have sepulchral chambers built with stones in horizontal layers, not so megalithic as those found in our tumuli, but of a more polished and artistic form of construction.

The age, too, in which these monuments were erected was essentially the age of bronze; not only are the ornaments and furniture found in the Etruscan tombs generally of that metal, but the tombs at Mycenæ and Orchomenos were wholly lined with it. The holes into which the bronze nails were inserted still exist everywhere, and some of the nails themselves are in the British Museum. It was also the age in which Solomon furnished his temple with all those implements and ornaments in brass—properly bronze—described in the Bible,[9] and the brazen house of Priam and fifty such expressions show how common the metal was in that day. All this, however, does not prove that iron also was not known then. In the Egyptian paintings iron is generally represented as a blue metal, bronze as red, and throughout they are carefully distinguished by these colours. Now, in the tombs around the pyramids, and of an age contemporary with them, there are numerous representations of blue swords as there are of red spear-heads, and there seems no reason for doubting that iron was known to the Greeks before the war of Troy, to the Israelites before they left Egypt (1320 B.C.), or to the Etruscans when they first settled in Italy. Hesiod's assertion that brass was known before iron may or may not be true.[10] In so far as his evidence is concerned we learn from it that iron was certainly in use long before his time (800 B.C.); so long indeed that he does not pretend to know when or by whom it was invented, and the modes of manufacturing steel—ἀδάμας—seem also to have been perfectly known in his day.

In India, too, as we shall see when we come to speak of that country, the extraction of iron from its ores was known from the earliest ages, and in the third or fourth century of our era reached a degree of perfection which has hardly since been surpassed. The celebrated iron pillar at the Kutub, near Delhi, which is of that age, may probably still boast of being the largest mass of forged iron that the world yet possesses, and attests a wonderful amount of skill on the part of those who made it.

When from these comparatively civilized modes of sepulture we turn to the forms employed in our own country, as described by Thurnam[11] or Bateman,[12] we are startled to find how like they are, but, at the same time, how infinitely more rude. They are either long barrows covering the remains of a race of dolicocephalic savages laid in rudely-framed cists, with implements of flint and bone and the coarsest possible pottery, but without one vestige of metal of any sort, or circular tumuli of a brachycephalic race shown to have been slightly more advanced by their remains being occasionally incinerated, and ornaments of bronze and spear-heads of that metal being also sometimes found buried in their tombs.

According to the usual mode of reasoning on these subjects, the long-headed people are older than the broad-pated race, the one superseding the other, and both must have been anterior to the people on the shores of the Mediterranean, for these were familiar with the use of both metals, and fabricated pottery which we cannot now equal for perfection of texture and beauty of design.

The first defect that strikes one in this argument is that if it proves anything it proves too much. We certainly have sepulchral barrows in this country of the Roman period, the Bartlow hills, for instance—of which more hereafter—and Saxon grave mounds everywhere; but according to this theory not one sepulchre of any sort between the year 1200 B.C. and the Christian era. All our sepulchres are ruder, and betoken a less advanced stage of civilization than the earliest of those in Greece or Etruria, and therefore, according to the usually accepted dogma, must be earlier.

It may be argued, however, that several are older than the Argive examples. That the Jersey tomb (woodcut No. 11), not- withstanding the coin of Claudius, is older, because more rude, than the Treasury at Mycenæ (woorlcut No. 4); but that the Bartlow hills and the Derbyshire dolmens and tumuli above alluded to (page 11 et seqq.), containing coins of Valentinian and the Roman Emperors, are more modern. Such an hypothesis as this involves the supposition that there is a great gap in the series, and that after discoutinuing the practice for a 1000 or 1500 years, our forefathers returned to their old habits, but with ruder forms than they had used before, and after continuing them for five or six centuries, finally abandoned them. This is possible, of course, but there is absolutely no proof of it that I know. On the contrary, so far as our knowledge of them at present extends, the whole of the megalithic rude stone monuments group together as one style as essentially as the Classical or Gothic or any other style of architecture. No solution of continuity can be detected anywhere. All are—it may be—prehistoric; or all, as I believe to be the case, belong to historic times. The choice seems to be between these two categories; any hypothesis based on the separation into a historic and a prehistoric group, distinct in characteristics as in age, appears to be utterly untenable.

The argument derived from the absence of iron in all our sepulchres also proves more than is desirable. The Danish antiquaries all admit that iron was not known in that country before the Christian era. Our antiquaries, from the testimony of Cæsar as to its use in war by the Britons, are forced to admit an earlier date, but it is hardly, if ever, found in graves. It is, on the other hand, perhaps correct to assume that its use was known in Egypt 3000 years before Christ; even if this is disputed, it certainly was known in the 18th dynasty, 15 centuries {sc|b.c.}}, and generally in the Mediterranean shortly afterwards. If, then, the knowledge of the most useful of metals took 3000 or even 1500 years to travel across the continent of Europe, it seems impossible to base any argument on the influence these people exercised on one another, or on the knowledge they may have had of each others' ways.

Or to take the argument in a form nearer home. When Cæsar warred against the Veneti in the Morbihan, he found them in possession of vessels larger and stronger than the Roman galleys, capable of being manœuvred by their sails alone, without the use of oars. Not only were these vessels fastened by iron nails, but they were moored by chain cables of iron. To manufacture such chains, the Veneti must have had access to large mines of the ore, and had long familiarity with its manufacture, and they used it not only for purposes on shore like the Britons, but in vessels capable of trading between Brest and Penzance—no gentle sea—and quite equal to voyages to the Baltic or other northern ports, which they no doubt made; it is asserted that, in 50 B.C., the Scandinavians were ignorant of the use of iron, though their country possessed the richest mines and the best ores of Europe.

The truth of the matter appears to be that, a century or so before Christ, England and Denmark were as little known to Greece and Italy, and as little influenced by their arts or civilization, as Borneo or New Zealand were by those of modern Europe at the beginning of the last century. Even now, with all our colonization and civilizing power, we have had marvellously little real influence on the native races, and were our power removed, all traces would rapidly disappear, and the people revert at once to what they were, and act as they were wont to do, before they knew us.

In like manner the North American Indians have been very little influenced by the residence of some millions of proselytizing Europeans among them for 200 years, and while this is so, it seems most groundless to argue because a few Phœnician traders may have visited this island to purchase tin, that, therefore, they introduced their manners and customs among its inhabitants; or because a traveller like Pytheas may have visited the Cimbrian Chersonese, or even penetrated nearly to the Arctic Circle, that his visit had, or could have, any influence on the civilization of these countries.[13] Civilization, as far as we can see, was only advanced in northern and western Europe by the extermination of the ruder races. Had this rude but effective method not been resorted to, we should probably have a stone-using people among us at the present day.

We may not know much of what happened in northern Europe before the time of the Romans, but we feel tolerably safe in asserting that none of the civilized nations around the Mediterranean basin ever colonized and settled sufficiently long in northern Europe to influence perceptibly the manners or usages of the natives. What progress was made was effected by migrations among themselves, the more civilized tribes taking the place of those less advanced, and bringing their higher civilization with them.

If these views are at all correct, it seems hopeless by any empirical theories founded on what we believe ought to have happened or on any analogies drawn from what occurred in other countries to arrive at satisfactory conclusions on the subject. It is at best reasoning from the unknown towards what we fancy may be found out. A much more satisfactory process would be to reason from the known backwards so far as we have a sure footing, and we may feel certain that by degrees as our knowledge advances we shall get further and further forward in the true track, and may eventually be able to attach at least approximative dates to all our monuments.

From this point of view, what concerns us most, in the first instance at least, is to know how late, rather than how early, our ancestors buried in tumuli. We have, for instance, certainly, the Bartlow Hills, just alluded to, which are sepulchres of the Roman period, probably of Hadrian's time; and we have in Denmark the tumuli in which King Gorm and his English wife, Queen Thyra Danebode, were buried in A.D. 950. We probably also may be able to fill in a few others between these two dates, and add some after even the last. Thus, therefore, we have a firm basis from which to start, and working backwards from it may clear up some difficulties that now appear insuperable.

Dolmens.

The monuments alluded to in the last section were either the rude barrows of our savage ancestors, with the ruder cists, or the chambered tumuli of a people who, when we first became acquainted with them, had attained nearly as high a degree of civilization as any Turanian people are capable of attaining. The people who erected such buildings as the Tombs of Mycenæ or Orchomenos must have reached a respectable degree of organization. They possessed a perfect knowledge of the use of metals, and great wealth in bronze at least, and had attained to considerable skill in construction. Yet it is not difficult to trace back—in imagination, at least—the various steps by which a small rude chamber in a circular mound, just capable of protecting a single body, may by degrees have grown into a richly-ornamented brazen chamber, 50 or 60 feet in diameter and of equal height. Nor is it more difficult to foresee what this buried chamber would have become, had not the Aryan occupation of Greece—figured under the myth of the return of the Heracleidæ—put a stop to the tomb-building propensities of the people. Before long it must have burst from its chrysalis state, and assumed a form of external beauty. It must have emerged from its earthen envelope, and taken a form which it did take in Africa[14] a thousand years afterwards,—a richly-ornamented podium, surmounted by a stepped cone and crowned by a stele. In Greece it went no further, and its history and its use were alike strange to the people who afterwards occupied the country.

In Italy its history was somewhat different. The more mixed people of Rome eagerly adopted the funereal magnificence of the Etruscans, and their tumuli under the Empire became magnified into such monuments as the Tomb of Augustus in the Campus Martius, or the still more gorgeous mausoleum of Hadrian, at the foot of the Vatican hill.

In like manner, it would not be difficult by the same process to trace the steps by which the rude tepés of the Tartar steppes bloomed at last into the wondrous domes of the Patan and Mogol Emperors of Delhi or the other Mahomedan principalities in the East. To do all this would form a most interesting chapter in the history of architecture, more interesting, perhaps, than the one we are about to attempt; but it is not the same, though both spring from the same origin. The people or peoples who eventually elaborated these wonderful mausoleums or domed structures affected, at the very earliest periods at which we become acquainted with them, what may be called Microlithic architecture. In other words, they used as small stones as they could use, consistently with their constructive necessities. These stones were always squared or hewn, and they always sought to attain their ends by construction, not by the exhibition of mere force. On the other hand, the people whose works now occupy us always affected the employment of the largest masses of stone they could find or move. With the rarest possible exceptions, they preferred their being untouched by a chisel, and as rarely were they ever used in any properly constructive sense. In almost every instance it was sought to attain the wished-for end by mass and the expression of power. No two styles of architecture can well be more different, either in their forms or motives, than these two. All that they have in common is that they both spring from the same origin in the chambered tumulus, and both were devoted throughout to sepulchral purposes, but in form and essence they diverged at a very early period. Long before we become acquainted with either; and, having once separated, they only came together again when both were on the point of expiring.

The Buddhist Dagobas are another offshoot from the same source, which it would be quite as interesting to follow as the tombs of the kings or emperors; for our present purposes, perhaps, more so, as they retained throughout a religious character, and being consequently freed from the ever-varying influence of individual caprice, they bear the impress of their origin distinctly marked upon them to the present day.

In India, where Buddhism, as we now know it, first arose, the prevalent custom—at least among the civilized races—was cremation. We do not know when they buried their dead; but in the earliest times of Buddhism they adopted at once what was certainly a sepulchral tumulus, and converted it into a relic shrine: just as in the early ages of Christianity the stone sarcophagus became the altar in the basilica, and was made to contain the relics of the saint or saints to whom the church was dedicated. The earliest monuments of this class which we now know are those erected by the King Asoka, about the year 250 B.C.; but there does not seem much reason for doubting that when the body of Buddha was burnt, and his relics distributed among eight different places,[15] Dagobas or Stupas may not then have been erected for their reception. None of these have, however, been identified; and of the 84,000 traditionally said to have been erected by Asoka, that at Sanchi[16] is the only one we can feel quite sure belongs to his age; but, from that date to the present day, in India as well as in Ceylon, Burmah, Siam, and elsewhere, examples exist without number.

All these are microlithic, evidently the work of a civilized and refined people, though probably copies of the rude forms of more primitive races. Many of them have stone enclosures; but, like that at Sanchi, erected between 250 B.C. and 1 A.D., so evidently derived from carpentry that we feel it was copied directly, like all the Buddhist architecture of that age, from wooden originals. Whether it was from the fashion of erecting stone circles round tumuli, or from what other cause, it is impossible now to say; but as time went on the form of the rail became more and more essentially lithic, and throughout the middle ages the Buddhist tope, with its circle or circles of stones, bore much more analogy to the megalithic monuments of our own country than did the tombs just alluded to; and we are often startled by similarities which, however, seem to have no other cause than their having a common parent, being, in fact, derived from one primæval original. There is nothing in all this, at all events, that would lead us to the conclusion that the polished stone monuments of India were either older or more modern than the rude stone structures of the West. Each, in fact, must be judged by its own standard, and by that alone.

For the proper understanding of what is to follow the distinctions just pointed out should always be borne in mind, as none are more important. Half indeed of the confusion that exists on the subject arises from their having been hitherto neglected. There is no doubt that occasional similarities can be detected between these various styles, but they amount to nothing more than should be expected from family likenesses consequent upon their having a common origin and analogous purposes. But, except to this extent, these styles seem absolutely distinct throughout their whole course, though running parallel to one another during the whole period in which they are practised. If this is so, any hypothesis based on the idea that the microlithic architecture either preceded or succeeded to the megalithic at once falls to the ground. Nor, if these distinctions are maintained, will it any longer be possible to determine any dates in succession in megalithic art from analogies drawn from what may have happened at any period or place among the builders of microlithic structures. The fact which we have got to deal with seems to be that the megalithic rude stone art of our forefathers is a thing by itself—a peculiar form of art arising either from its being adopted by a peculiar race or peculiar group of races among mankind, or from its having been practised by people at a certain stage of civilization, or under peculiar circumstances, and this it is our business to try to find out and define. But to do this, the first thing that seems requisite is to put aside all previously conceived notions on the subject, and to treat it as one entirely new, and as depending for its elucidation wholly on what can be gathered from its own form and its own utterances, however indistinct they may at first appear to be.

Bearing this in mind, we have no difficulty in beginning our history of megalithic remains with the rude stone cists, generally called kistvaens, which are found in sepulchral tumuli. Sometimes these consist of only four, but generally of six or more stones set edgeways, and covered by a capstone, so as to protect the body from being crushed. By degrees this kistvaen became magnified into a chamber, the side stones increasing from 1 or 2 feet in height to 4 or 5 feet, and the capstone becoming a really megalithic feature 6 or 10 feet long, by 4 or 5 feet wide, and also of considerable thickness. Many of these contained more than one funeral deposit, and they consequently could not have been covered up by the tumuli till the last deposit was placed in them. This seems to have been felt as an inconvenience, as it led to the third step, namely, of a passage communicating with the outer air, and formed like the chambers of upright stones, and roofed by flat ones extending across from side to side. The most perfect example of this class is perhaps that in the tumulus of Gavr Innis in the Morbihan. Here is a gallery 42 feet long and from 4 to 5 feet wide, leading to a chamber 8 feet square, the whole being covered with sculptures of the most elaborate character.

A fourth stage is well illustrated by the chambers of New Grange, in Ireland, where a similar passage leads to a compound or cruciform chamber rudely roofed by converging stones. Another beautiful example of the same class is that of Maeshow in the Orkneys, which, owing to the peculiarity of the stone with which it is built, comes more nearly to the character of microlithic art than any other example. It is probably among the last if not the very latest of the class erected in these isles, and by a curious concatenation of circumstances brings the megalithic form of art very nearly up to the stage where we left its microlithic sister at Mycenæ some two thousand years before its time.

All this will be made clearer in the sequel, but meanwhile there are one or two points which must be cleared up before we can go further. Many antiquaries insist that all the dolmens[17] or cromlechs,[18] which we now see standing free, were once covered up and buried in tumuli.[19] That all the earlier ones were so, is more than probable, and it may since have been originally intended also to cover up many of those which now stand free; but it seems impossible to believe that the bulk of those we now see were ever hidden by any earthen covering.

Probably at least one hundred uncovered dolmens in these islands could be enumerated, which have not now a trace of any such envelope. Some are situated on uncultivated heaths, some on headlands, and most of them in waste places. Yet it is contended that improving farmers at some remote age not only levelled the mounds, but actually carted the whole away and spread it so evenly over the surface that it is impossible now to detect its previous existence. If this had taken place in this century when land has become so valuable and labour so skilled we might not wonder, but no trace of any such operation occurs in any living memory. Take for instance Kits Cotty House, it is exactly now where it was when Stukeley drew it in 1715,[20] and there was no tradition then of any mound ever having covered it. Yet it is contended that at some earlier age when the site was probably only a sheep-walk, some one carried away the mound for some unknown purpose, and spread it out so evenly that we cannot now find a trace of it. Or take another instance, that at Clatford Bottom,[21] also drawn by Stukeley. It stands as a chalky flat to which cultivation is only now extending, and which certainly was a sheep-walk in Stukeley's time, and why, therefore, any one should have taken the trouble or been at the expense of denuding it is very difficult to understand, and so it is with nine-tenths of the rest of them. In the earlier days when a feeling for the seclusion of the tomb was strong, burying them in the recesses of a tumulus may have been the universal practice, but when men learned to move such masses as they afterwards did, and to poise them so delicately in the air, they may well have preferred the exhibition of their art to concealing it in a heap which had no beauty of form and exhibited no skill. Can any one for instance conceive that such a dolmen as that at Castle Wellan in Ireland

ever formed a chamber in barrow, or that any Irish farmer would ever have made such a level sweep of its envelope if it ever had one? So in fact it is with almost all we know. When a dolmen was intended to be buried in a tumulus the stones supporting the roof were placed as closely to one another as possible, so as to form walls and prevent the earth penetrating between them and filling the chambers, which was easily accomplished by filling in the interstices with small stones as was very generally done. These tripod dolmens, however, like that at Castle Wellan, just quoted, never had, or could have had walls. The capstone is there poised on three points, and is a studied exhibition of a tour de force. No traces of walls exist, and if earth had been heaped upon it the intervals would have been the first part filled, and the roof an absurdity, as no chamber could have existed. These tripod dolmens are very numerous, and well worth distinguishing, as it is probable that they will turn out to be more modern than the walled variety of the same class. But with our present limited knowledge it is hardly safe to insist on this, however probable it seems at first sight.

The question, however, fortunately, hardly requires to be argued, inasmuch as in Ireland, in Denmark,[22] and more especially in France, we have numerous examples of dolmens on the top of tumuli, where it is impossible they should ever have been covered with earth. One example for the present will explain what is meant. In the Dolmen de Bousquet in the Aveyron[23] the chamber is placed on the top of a tumulus, which from the three circlets of stone that surround it, and other indications, never could have been higher or larger than it now is.

So far as I know, none of these dolmen-crowned tumuli have been dug into, which is to be regretted, as it would be curious to know whether the external dolmen is the real or only a simulated tomb. My own impression would be in favour of the latter hypothesis, inasmuch as a true and a false tomb are characteristic of all similar monuments. In the pyramids of Egypt they coexisted. In every Buddhist tope, without exception, there is a Tee, which is in every case we know only a simulated relic-casket. Originally it may have been the place where the relic was deposited, and as we know of instances where relics were exposed to the crowd on certain festivals, it is difficult to understand where they were kept, except in some external case like this. In every instance, however, in which a relic has been found it has been in the centre of the Tope and never in the Tee. A still more apposite illustration, however, is found in the tombs around Agra and Delhi. In all those of any pretension the body is buried in the earth in a vault below the floor of the tomb and a gravestone laid over if, but on the floor of the chamber, under the dome, there is always a simulated sarcophagus, which is the only one seen by visitors. This is carried even further in the tomb of the Great Akbar (1556, 1605). Over the vault is raised a pyramid surrounded, not like this tumulus by three rows of stones, but by three rows of pavilions, and on the top, exposed to the air, is a simulated tomb placed exactly as this dolmen is. No two buildings could well seem more different at first sight, but their common parentage and purpose can hardly be mistaken, and it must he curious to know whether the likeness extends to the double tomb also.This, like many other questions, must he left to the spade to determine, but, unless attention is turned to the analogy above alluded to, the purpose of the double tomb may he misunderstood, even when found, and frequently, I suspect, has already been mistaken for a secondary interment.Circles.

Circles form another group of the monuments we are about to treat of, in this country more important than the dolmens to which the last section was devoted. In France, however, they are hardly known, though in Algeria they are very frequent. In Denmark and Sweden they are both numerous and important, but it is in the British Islands that circles attained their greatest development, and assumed the importance they maintain in all the works of our antiquaries which treat of megalithic art.

The cognate examples in the microlithic styles afford us very little assistance in determining either the origin or use of this class of monument. It might, nay has been suggested, that the podium which surmounts such a tumulus, for instance, that of the Cocumella (woodcut No. 5) would, if the mound were removed, suggest, or be suggested, by the stone circles of our forefathers. This podium, however, seems always to have been a purely constructive expedient, without any mystic or religious significance, for unless the base of an earthen mound is confined by a revêtement of this sort it is apt to spread, and then the whole monument loses that definition which is requisite to dignity.

The Rails of the Indian Buddhists at first sight seem to offer a more plausible suggestion of origin, but it is one on which it would be dangerous in the present state of our knowledge to rely too much; if for no other reason, for the one just given, that up to the time of Asoka, B.C. 250, they, like all the architecture of India, were in wood and wood only. Stone as a building material, either rude or hewn, was unknown in that country till apparently it was suggested to them by the Bactrian Greeks. Unless, therefore, we are prepared to admit that all our stone circles are subsequent, by a considerable interval of time, to the epoch of Asoka, they were not derived from India. My own impression is that all may ultimately prove to have been erected subsequently to the Christian Era, but till that is established we must look elsewhere than to India for our original form, and even then we have only got a possible analogy; and nothing approaching to a proof that any connexion existed between them.

The process in this country, so far as I can make out, was different, though tending to a similar result. The stone circles in Europe appear to have been introduced in supercession to the circular earthen mounds which surround the early tumuli of our Downs. These earthen enclosures still continued to be used, surrounding stone monuments of the latest ages, but, if I mistake not, they first gave rise to the form itself. Such a circle, for instance, as that called the Nine Ladies on Stanton Moor, I take to be a transitional example. The circular mound, which is 38 feet in diameter, enclosed a sepulchral tumulus, as was, no doubt, the case from time immemorial, but, in this instance, was further adorned and dignified by the circle of stones erected upon it. A century or so afterwards, when stone had become more recognized as a building material, the circular mound may have been disused, and then the stone circle would alone remain.

These stone circles are found enclosing tumuli, as in the Dolmen de Bousquet (woodcut No. 8), in three rows, and sometimes five or seven rows are found. They frequently also enclose dolmens, either standing on the level plain or on tumuli, but often, especially in this country, they are found enclosing nothing that can be seen above ground. This has led to the assumption that they are "Things," comitia—or places of assembly—or, still more commonly, that they are temples, though, now that the Druidical theory is nearly abandoned, no one has been able to suggest to what religion they are, or were, dedicated. The spade, however, is gradually dispelling all these theories. Out of say 200 stone circles which are found in these islands, at least one-half, on being dug out, have yielded sepulchral deposits. One-quarter are still untouched by the excavator, and the remainder which have not yielded up their secret are mostly the larger circles. Their evidence, however, is at best only negative, for, till we know exactly where to dig, it would require that the whole area should be trenched over before we can feel sure we had not missed the sepulchral deposit. When, as at Avebury, the circle encloses an area of 28 acres,[24] and the greater part of it is occupied by a village, no blind digging is likely to lead to any result, or can be accepted as evidence.

Still the argument would be neither illegitimate nor illogical if, in the present state of the evidence, it were contended that all stone circles, up say to 100 feet diameter, were sepulchral, as nine-tenths of them have been proved to be, but that the larger circles were cenotaphic, or, if another expression is preferred, temples dedicated to the honour or worship of the dead, but in which no bodies were buried. But to admit—and it cannot now be denied—that all circles up to 100 feet are sepulchral, yet to assert that above that dimension they became temples dedicated to the sun, or serpents, or demons, or Druids, without any other change of plan or design but increased dimensions, appears a wholly untenable proposition.

All this will, it is hoped, be made more clear in the sequel when we come to examine particular examples, regarding which it is more easy to reason than merely from general principles; but in the meanwhile there is one other peculiarity which should be pointed out before proceeding further. It is that where great groups of circles are found, they—so far as is at present known—never mark cemeteries where successive generations of kings or chiefs were buried, but battle-fields. The circles, or dolmens, or cairns grouped in these localities seem always to have been erected by their comrades, to the memory of those who on these spots "fiercely fighting, fell," and are monuments as well of the prowess of the survivors as of those who were less fortunate. The proof of this also must depend on individual examples to be brought forward in the following pages. It does not, however, seem to present much difficulty, the principal point in the argument being that they are generally found in solitary places far removed from the centres of population, or are sometimes single and that they show no progression. Had they been cemeteries or sepulchres of kings, several would undoubtedly have been found grouped together; progression and individuality would have been observed; and lastly, they are just such monuments as an army could erect in a week or a month, but which the inhabitants of the spot could not erect in years, and could not use for any conceivable purpose when erected.

Avenues.

It is somewhat unfortunate that no recognized name has yet been hit upon for this class of monument. Alignment has been suggested, but the term is hardly applicable to two rows of stones, for instance, leading to a circle. Parallellitha is, at best, a barbarous compound, and as such better avoided. Though therefore, the word avenues can hardly be called appropriate to rows of stones leading from nowhere to no place, and between which there is no evidence that anybody ever was intended to walk, still it seems the least objectionable expression that has yet been hit upon, and as such it will be used throughout.

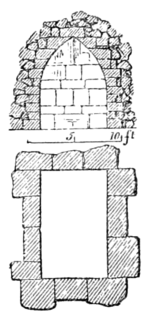

These avenues are of two classes. First, those leading to circles. About the origin of this class there can be very little hesitation. They represent externally the passages in tumuli which lead to the central chamber; take, for instance, this example from a now destroyed[25] tumulus near St. Helier, in Jersey.[26] The circular chamber was 24 feet in diameter, and contained originally seven little cells, each roofed by a single slab of stone. This circular area was approached by an avenue, 17 feet long at the time of its destruction, which was roofed throughout the whole length with slabs of stone. The central chamber never, however, appears to have been vaulted, so that access to the tombs through this passage could never have been possible after the mound was finished. The chamber was found filled with earth, and the whole monument covered up by a tumulus of considerable extent. It need hardly be observed that it is more unlikely that any people should cover up such a monument at any subsequent age, than that they should dig out such monuments and leave them standing without their envelopes, as is so generally assumed. The tumulus was removed, because the officer in command of the neighbouring fort wanted a level parade-ground. As it stood uncovered it was a miniature Avebury, and the position of its cells may give us a hint where the bodies may be found there—near the outer circle of stones, where they have not been looked for. But of this hereafter. It is meanwhile evident that while these monuments were in course of erection they stood as shown in the last woodcut, and it is also tolerably clear that when people became familiar with their aspect in this state, they may have learned to regret hiding under a heap of earth what we certainly would have thought more interesting as it was. In like manner, as John Stuart well remarks, "If the cairns at New Grange were removed, the pillars would form another Callernish."[27] It is true, however, that if the Jersey monument is the type of Avebury, the latter must be comparatively modern, as a coin of Claudius, found in one of the cells at St. Helier,[28] probably fixes its date. Again, as we expect to be able to prove that New Grange is subsequent to the Christian era, Callernish must be more modern also. Be this as it may, I think there can be very little doubt that these exposed circles, with their avenues, took their rise, as in the case of dolmens, from people becoming familiar with their forms before they were covered up, and eventually reconciling themselves to dispense with the envelope. In the case of the circles, the new plan was capable of infinitely greater extension than in that of the dolmens; but the process seems to have been the same in both instances.

Before leaving the Jersey circle, if any one will compare it with the chamber at Mycenæ (woodcut No. 4), they can hardly fail to perceive the close similarity and probable identity of destination that exists between them; but as the island example is very much ruder, according to the usual reasoning it must be the more ancient of the two. This, however, is the capital fallacy which has pervaded all reasoning on the subject hitherto. It is true that nothing can be more interesting or more instructive than to trace the progress of the Classical, the Mediæval, and the Indian styles through their ever-changing phases, or to watch the influence which one style had on the other. That progress was, however, always confined within the limits of a nation, or community of nations, and the influence limited to such nations as from similarity of race or constant intercourse were in position to influence reciprocally not only the architecture, but their arts and feelings. In order to establish this in the present instance, we must prove that there was such community of race and frequency of intercourse between the Channel Islands and Greece 1000 years B.C., that the latter would copy the other, or rather that 2000 years B.C. the Channel Islanders gave the Greeks those hints which they were enabled to elaborate, and of which the chambers at Mycenæ about the time of the Trojan war were the result. Had this been the case the influence could hardly have ceased as civilization and inter- course with other countries increased, and we ought to find Tholoi in great perfection in these islands, and probably temples and arts in all the perfection to which they were afterwards expanded in Greece. In fact, we get into such a labyrinth of conjecture, that no escape seems possible. It would be almost as reasonable to argue that the images on Easter Island, which we know continued to be carved in our day, were prehistoric, because they are so much ruder than the works of Phidias. The truth is, that where we cannot trace community of race or religion, accompanied by constant and familiar intercourse, we must take each people as doing what their state of civilization enabled them to accomplish, wholly irrespective of what was doing or had been done by any other people in any other part of the world. All that it is necessary to assume in this case is, that a dead-revering ancestral-worshipping people wished to do honour to the departed, as they knew or heard was done by other races of their family of mankind elsewhere, and that they did it in the best manner the state of the arts among them admitted of—rudely, if they were in a low state of civilization, and more perfectly if they had advanced beyond that stage in which rude forms could be tolerated.

It is much more difficult to trace the origin of the avenues which are not attached to circles, and do not lead to any important monuments. Nothing that is buried at all resembles them in form, and no erections in the corresponding microlithic style, either in the Mediterranean countries or in India, afford any hints which would enable us to suggest their purpose. We are thus left to guess at their uses solely from the evidence which can be gathered from their own form and position, and from such traditions as may exist; and these, it seems, have not hitherto been deemed sufficient to establish even a plausible hypothesis capable of explaining their intention.

Take, for instance, such an example as the parallel lines of stones near Merivale Bridge on Dartmoor. They certainly do not form a temple in any sense in which that word is understood by any other people or in any age with which we are acquainted. They are not procession paths, inasmuch as both ends are blocked up; and, though it is true the sides are all doors, we cannot conceive any procession moving along their narrow gangway, hardly three feet in width. The stones that compose the sides are only two and three feet high; so that, even if placed side by side, they would not form a barrier, and, being three to six feet apart, they are useless except to form an "alignment." There is no place for an image, no sanctuary or cell; nothing, in fact, that can be connected with any religious ceremonial.

If the inhabitants of the place had really wanted a temple, in any sense in which we understand the term, there is a magnificent tor, a few hundred yards off to the northward, where Nature has disposed some magnificent granite blocks so as to form niches such as human hands could with difficulty imitate. All that was wanted was to move the smaller blocks, lying loose in front of it, a few yards to the right or left, and dispose them in a semi-circle or rectangular form, and they would have one of the most splendid temples in England in which to worship the images which Cæsar tells us they possessed.[29] They, however, did nothing of the kind. They went to a bare piece of moorland, where there were no stones, and brought those we find there, and arranged them as shown on the plan; and for what purpose?

AVENUES, CIRCLES AND CROMLECH, NEAR MERIVALE BRIDGE, DARTMOOR.

The only answer to the question that occurs to me is that these stones are intended to represent an army, or two armies, drawn up in battle array; most probably the former, as we can hardly understand the victorious army representing the defeated as so nearly equal to themselves. But if we consider them as the first and second line, drawn up to defend the village in their rear—which is an extensive settlement—the whole seems clear and intelligible. The circle in front would then represent the grave of a chief; the long stone, 40 yards in front, the grave of another of the "menu" people; and the circles and cromlech in front of the first line the burying-places of those who fell there.

There is another series of avenues at Cas Tor, on the western edge of Dartmoor,[30] some 600 yards in length, which is quite as like a battle array as this, but more complex and varied in plan. It bends round the brow of the hill, so that neither of the ends can be seen from the other, or, indeed, from the centre; and it is as unlike a temple or anything premeditated architecturally as this one at Merivale Bridge. There are several others on Dartmoor, all of the same character, and not one from which it seems possible to extract a religious idea.

When speaking of the great groups of stones in England and France, we shall frequently have to return to this idea, though then basing it on traditional and other grounds; but, meanwhile, what is there to be said against it? It is perhaps not too much to say that in all ages and in all countries soldiers have been more numerous than priests, and men have been prouder of their prowess in war than of their proficiency in faith. They have spent more money for warlike purposes than ever they devoted to the service of religion, and their pæans in honour of their heroes have been louder than their hymns in praise of their gods. Yet how was a rude, illiterate people, who could neither read nor write, to hand down to posterity a record of its victories? A mound, such as was erected at Marathon or at Waterloo, is at best a dumb witness. It may be a sepulchre, as Silbury Hill was supposed to be; it may be the foundation of a caer, or fort, as many of those in England certainly were; it may be anything, in short. But a savage might very well argue: "When any one sees how and where our men were drawn up when we slaughtered our enemies, can lie be so stupid as not to perceive that here we stood and fought and conquered, and there our enemies were slain or ran?" We, unfortunately, have lost the clue that would tell us who "we" and "they" were in the instance of the Dartmoor stones at least; but uncultivated men do not take so mean a view of their own importance as to fancy this possible.

This theory has at least the merit of accounting for all the facts at present known, and of being at variance with none, which is more than can be said for any other that has hitherto been proposed. Till, therefore, something better is brought forward, it must be allowed to stand at least as a basis to reason upon, in order to explain the monuments we have to describe in the following pages.

Menhirs.

The Menhirs, or tall stones,[31] form the last of the classes into which we have thought it necessary for the present, at least, to divide the remains of which we are now treating. They occur in all the megalithic districts, but from their very singleness and simplicity, it is almost more difficult to ascertain their purpose than it is that of any more complicated monuments; nor do the analogies from the cognate microlithic styles help us much. The stones mentioned in the early books of the Old Testament, though often pressed into the service, were all too small to bear any resemblance to those we are now concerned with. Neither Greece nor Etruria help us in the matter, and though it is true that the Buddhists in India, from Asoka's time downward, were in the habit of setting up Lâts or Stambas, it seems with them to have been always, or nearly so, for the purpose of bearing inscriptions, which is certainly not a distinguishing characteristic of our Menhirs. It is true that we have in Scotland two stones. The Cat stone near Edinburgh, bearing the name of Vetta, the grandson of Hengist (who probably was slain in battle there),[32] and the Newton stone in Garioch, which is still unread. We have also one in France near Brest,[33] equally illegible, and no doubt others exist. Perhaps these may be considered as early lispings of an infant, which certainly are the preludes of perfect speech, and only to be found where that power of words must afterwards exist. Here the analogy is, to say the least of it, remote.

There also are, especially in Ireland, but also in Wales and in Scotland, a great number of stones with Ogham inscriptions. So far as these have been made out they seem to be mere headstones of graves, intimating that A, the son of B, lies buried there. A custom, it need hardly be observed, that continues to the present day in every cemetery in the land. The fact seems to be that so soon as the use of stone was suggested and men were sufficiently advanced to be able to engrave Oghams, it was at once perceived that a stone pillar with an inscription upon it was not only a more durable but a more intelligent and intelligible record of a man's life or death than a simple mound of "undistinguishable earth." It in consequence rapidly superseded the barrow, and has continued in use to the present time, and been adopted by both Christians and Mahomedans, by all, in fact, who bury, as contradistinguished from those who burn their dead.

In Scotland the story of the stones is slightly different, A great many of these are no doubt cat stones or battle memorials, but as they have not even Ogham inscriptions, they tell no tale. It is doubtful, indeed, if an Ogham inscription could describe a battle, or anything more complex than a genealogy, and still more so if it did whether we could read it. But without it how can we say what they are? If, for instance, the battle of Largs had not been fought in historic times, how could we tell that the tall stone that now marks the spot was erected in the thirteenth century? Or how, indeed, can we feel sure of the history of any one? By degrees, however, in Scotland they faded into those wonderful sculptured stones which form so marked and so peculiar a feature of Pictland. Whether we shall ever get a key to the hieroglyphics with which these stones are covered is by no means clear, but even if we do they probably will not tell us much. They certainly contain neither names nor dates, but even now their succession can be made out with tolerable distinctness. The probability seems to be that the figures on them are tribal marks or symbols of rank, and, as such, would convey very little information if capable of being read.

It is easy to trace the perfectly plain obelisk being developed into such as the Newton stones, which have only one or two Pagan symbols, but are certainly subsequent to the Christian era. From these we advance to those on the back of which the Christian cross timidly appears, and which certainly date after St. Columba's time (A.D. 563), and from that again to the erection of Sweno's stone, near Forres, in the first years of the eleventh century, where the cross occupies the whole of the rear, and an elaborate bas-relief supersedes the rude symbols in the front.

In Ireland the rude stones do not appear to have gone through the "symbol stage," but early to have ripened into the sculptured cross, for it was not from a timidly engraved cross as in Scotland that they took their origin. The Irish crosses at once boldly adopted the cross-arms, surrounded by a glory, with the other characteristics of that beautiful and original class of Christian monuments.

In France the menhir was early adopted by the Christians; so early that it has generally been assumed that those examples which we see surmounted by a cross were pagan monuments, on which at some subsequent time Christians have added a cross. This, however, certainly does not appear to have been always the case. In such a cross, for instance, as that at Lochcrist, the menhir and the cross are one, and made for one another, and similar examples occur at Cape St. Matthieu, at Daoulas, and in other places in Brittany.[34] In France the menhir, after being adopted by the Christians, does not seem to have passed through the sculptured stage[35] common to crosses in Scotland and Ireland, but to have bloomed at once into the Calvary so frequent in Brittany. Here the cross stands out as a tall tree, and the figures are grouped round its base, but how early this form was adopted we have no means of knowing.

In Denmark the modern history of the Bauta stones, as the grave or battle stones are there called, is somewhat different. They early received a Runic as the Irish received an Ogham inscription, but Denmark was converted at so late an age to Christianity (the eleventh century) that her menhirs never passed through the early Christian stage, but from Pagan monuments sank at once into modern gravestones, with prosaic records of the birth and death of the dead man whose memory they were erected to preserve.

In all these instances we can trace back the history of the menhirs from historic Christian times to non-historic regions when these rude stone pillars, with or without still ruder inscriptions, were gradually superseding the earthen tumuli as a record of the dead. It is as yet uncertain whether we can follow back their history with anything like certainty beyond the Christian era. This, however, is just the task to which antiquaries should address themselves. Instead of reasoning as hitherto from the unknown to the known, it would be infinitely more philosophical to reason from the known backwards. By proceeding in this manner every step we make is a positive gain, and eventually may lead us to write with certainty about things that now seem enveloped in mist and obscurity.

- ↑ It is so curious as almost to justify Piazzi Smyth's wonderful theories on the Subject. But there is no reason whatever to suppose that the progress of art in Egypt differed essentially from that elsewhere. The previous examples are lost, and that seems all.

- ↑ Herodotus, ii. 123; and Sir Gardner Wilkinson's 'Ancient Egyptians,' second series, i. 211; ii. 440 et passim.

- ↑ Herod, i. 93.

- ↑ 'Lydische Königsgräber,' Berlin, 1859.

- ↑ I am, of course, aware that the now fashionable craze is to consider Troy a myth. So far, however, as I am capable of understanding it, it appears to me that the ancient solar myth of Messrs. Max Müller and Cox is very like mere modern moonshine.

- ↑ Paus. ii. ch. 16; 'Dodwell's Pelasgic Remains in Greece and Italy,' pl. 11.

- ↑ Dodwell, l. c. p. 13.

- ↑ More particulars and illustrations of these tombs will be found in the first volume of my 'History of Architecture,' and they need not, therefore, be repeated here.

- ↑ Kings, vii. 13 et seqq.; 2 Chron. iv. 1 et seqq.

- ↑ Hesiod. 'Works and Days,' 1. 150.

- ↑ 'Crania Britannica,' passim. 'Archæologia,' xxxviii.

- ↑ 'Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire,' 1848. 'Ten Years' Diggings,' 1861.

- ↑ See controversy between Sir George Cornewall Lewis in his 'Astronomy of the Ancients,' p. 467 et seqq. and Sir John Lubbock, in 'Prehistoric Times,' p. 59 et seqq. with regard to Pytheas and his discoveries.

- ↑ In the Kubber Roumeia, in the Sahil, or the Madraeen, near Blidah.

- ↑ See Turnour in 'J. A. S. B.' vii. p. 1013.

- ↑ Cunningham, 'Bilsah Topes,' passim; and 'Tree and Serpent Worship,' by the author, p. 87-148.

- ↑ Dolmen is derived from the Celtic word Daul, a table—not Dol, a hole—and Men or Maen, a stone.

- ↑ Crom, in Celtic, is crooked or curved, and therefore wholly inapplicable to the monuments in question; and lech, stone.

- ↑ The most zealous advocate of this view is the Rev. W. C. Lukis, who, with his father, has done such good service in the Channel Islands. His views are embodied in a few very distinct words in the Norwich volume of the 'Prehistoric Congress,' p. 218, but had previously been put forward in a paper read to the Wiltshire Archælogical Society in 1861, and afterwards in the 'Kilkenny Journal.' v. N. S. p. 492 et seqq.

- ↑ 'lter Curiosum,' pl. xxxii. and xxxiii.

- ↑ 'Stonehenge and Avebury,' pl. xxxii. xxxiii. and xxxiv.

- ↑ Madsen. 'Antiquites Prehistoriques,' pl. 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10.

- ↑ Norwich volume of 'Prehistoric Congress' p. 355, pl. vi.

- ↑ Sir H. Colt Hoare, 'Ancient Wiltshire,' ii. 71.

- ↑ The stones of which it was composed were transported by General Conway to Park Place, near Henley-on-Thames, and re-erected there.

- ↑ 'Archæologia,' viii. p. 384.

- ↑ 'Sculptured Stones of Scotland,' ii. Introd. p. 25.

- ↑ 'Archæologia,' viii. p. 385.

- ↑ Deum maxime Mercurium colunt. Hujus sunt plurima simulacra. 'Bell. Gal.' vi. 16.

- ↑ Sir Gardner Wilkinson in 'Journal, Archæological Association,' xvi. p. 112, pl. 6 for Cas Tor, and pl. 7 for Merivale Bridge.

- ↑ From Maen, as before, stone, and hir—high, Minar is supposed to be the same word. It cannot, at least, be traced to any root in any Eastern language.

- ↑ 'Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland,' iv. 119 et seqq.

- ↑ 'Freminville, Finistère,' pl. iv. p. 248.

- ↑ All these, and many others, are to be found illustrated in Taylor and Nodier's 'Voyage Pittoresque dans l'ancienne Bretagne;' but as the plates in that work are not numbered they cannot be referred to.

- ↑ I know only one instance of sculptured stone in France; it occurs near the Chapelle St. Marguerite in Brittany.