Sunset (magazine)/Volume 31/The Land Where Life Is Large

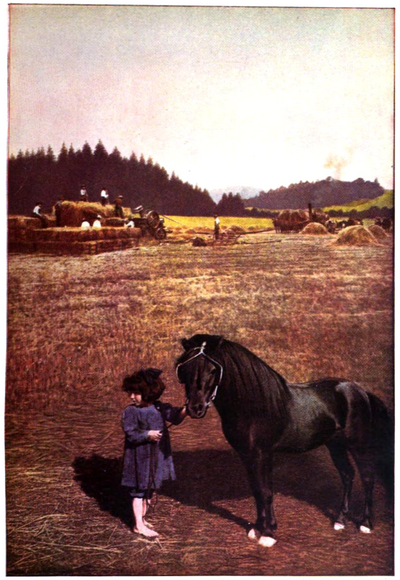

The Land Where Life Is Large

A Story of Oregon Farms for Other Farmers

By WILLIAM R. LIGHTON

Author of: The Story of an Arkansas Farm

We're a restless lot, we Americans. We hold the world's record for restlessness. Ever since our great great-and-then-some-grandsires fought for their first feeble foothold on the Atlantic side we've been drifting and shifting, drifting and shifting, forever on the move, forever on the hunt for something. Think of it: in fifty years we've mastered half a continent, making history as it was never made before.

What have we been hunting for? We haven't been spending all this time and money and blood on a mere hunt for change and excitement and adventure. It isn't the dream of wealth that's enticed us, nor yet the vision of empire. Those things are all well enough in their way; but none of those things is our master-passion, our real heart's desire. You know it, too.

What we've been looking for, more than all else, above all else, has been a place where we might come to rest in peace; a place of refuge from the heart—burning, soulracking, tormenting wandering. Appearances are against us, but in our heart of hearts we're home-makers. That's what we've been aiming at, through these centuries of stormy adventuring. Almost to a man we're cherishing fond sweet hopes of finding, some time, somewhere, a place where the sword of anxious endeavor may be beaten into the tools of the home-builder; a place where we may walk jocund through golden days of dear delight, finding that life has broadened, deepened, become large. Maybe that's too flossy a way of saying it; but you know it's true. That's what you want; that's what I want—and we shan't be happy till we get it.

Not many of us have actually come upon the real thing. For most of us, the real thing has seemed to lie always somewhere beyond the rim of the horizon, forever coaxing us on, forever vanishing, just ahead of us, in the mists of distance. Lots and lots of us have come to the point of thinking that in holding out the hope the gods have been mocking us. Lots and lots of us are about ready to give up the quest with a regretful sigh and try to content ourselves as best we can with some sort of a compromise. Lots and lots of us have made up our minds that the thing we've seen in our visions is after all absolutely too good to be realized.

It isn't, though. Listen. I've just seen with my own eyes one of those rare and perfect places where life may have that supreme quality which satisfies longing—not merely length, breadth and substance, but also that fourth dimension of divine content. No, I'm not trying to fool you. It's too solemn a matter for fooling. The Willamette valley of Oregon is a land where life is large.

This wonderful valley lies tucked snugly away between the Cascade mountains on the east and the Coast Range on the west. Its mouth is at Portland, at the junction of the Willamette river with the Columbia; its upper end is in the highlands of Lane county, off to the south. The valley proper holds about 5,000,000 acres of the most fertile soil in the world, a soil equal to any demand that may be made upon it. Today it is carrying a population, outside the city of Portland, of about 200,000 people. Brought to its fullest development, this land will one day support one prosperous, happy human being on every acre—five millions of people whose life will embody the highest and best things in civilization. Yes, I know well enough that prophecy is a dangerous business, under common conditions; but here's a case where the prophet has a cinch. He can't miss it; he can see it with one eye tied behind him.

Nobody can tell this story adequately, no matter who he is nor what his gifts. It seems absurd to try. When the pen has done its utmost and begins to stutter impotently, the best must still remain unwritten. We haven't yet made the words THE FRUIT OF THE VALLEY VINES

Wheat-growing was the chief concern of the pioneer farmers in the country of the Willamette. Wheat was just about the only farm product that figured in shipments out of the valley. A simple list of present-day products of this valley soil would fill pages. At a recent county fair one farmer alone exhibited 267 varieties of products grown on his own farm

REAL BONANZA FARMING

Day by day the big wheat farms of the old time are being split up into farm homes, the average size of which grows less and less. In the heart of the valley, a tract of 640 acres which had been owned and operated by a single farmer up to the year 1910 is today supporting forty-two families, every one of them faring better than the original owner fared

We're an emotional people, but we have our practical side. So has this story. Let's try to consider, as soberly as we can, some of the practical features of Willamette valley life. We can't go carefully into detail in a few pages; we'll have to look at our facts rather in the mass.

The best blood of America pioneered this country of the Willamette, making the first really permanent settlements something more than sixty years ago. Wheat-growing was the chief concern of those pioneer farmers, and wheat-growing held first place for a long time, to the exclusion of almost everything else. The land holdings were large in those days, and the production of wheat was carried on according to the old methods of extensive farming—wheat, wheat, wheat, year after year. Wheat was just about the only farm product that figured then in shipments out of the valley. Several lines of steamboats brought down the wheat from the farms to Portland, and carried back most of what the wheat farmers ate and used. Life then was slow and easy-going. Modern ideas of farming and farm management hadn't yet caught hold.

That couldn't last, though. Soils, climate, location and every other circumstance made this an ideal place for modern diversified farming in its best form. Wheat farming had to give way before it. That's been the history of every one-crop district. The production of a single crop over a wide area, to the exclusion of others, is unsound in theory, tremendously wasteful in practice. "Bonanza farming" sounds mighty fine and large and princely. Fortunes have been made at it—by the favored few; but that sort of farming has always spelled industrial and social stagnation for the region indulging it. Exclusive cotton—growing has kept the farm life of the southern Gulf States at a standstill for generations. While the states of the Upper Mississippi valley were devoted exclusively to growing and selling grain. life there was hardly worth living. So long as the Plains country was abandoned entirely to stock grazing. there was no social life worth mentioning. That's inevitably true everywhere. High civilization always waits on the development of many and various resources. Bonanza money-making is only part of life, as we're beginning to understand it. Mind you, this isn't said in disparagement of the earlier farmers. Theirs was a necessary first step; but it was only the toddling first step of an industrial infant just beginning to walk. Naturally, later steps have been firmer, surer. It was these later steps that really enabled the Willamette valley to "get there."

A simple list of present-day products of this valley soil would fill pages. At a recent county fair, one farmer alone exhibited 267 varieties of products grown on his own farm. Conditions here enable the production of all temperate zone foodstuffs at the lowest possible cost and of the highest quality.

It's only within the last ten years that diversified farming really got upon its feet in this valley. Let's not try now to forecast what it will accomplish in the future; let's look instead at what has been already actually accomplished. That's the best part of the story, right now.

This valley, with its 5,000,000 acres of cultivable land, now has only about 1,000,000 acres actually under cultivation, with about 250,000 acres more in use as pasture and meadow. The valley holds 22,000 farm homes, with about two-thirds of the people of the valley living on the farms and in the small farm villages. Hardly one acre has yet been brought up to its full producing power. That work is still in its first stages.

But mark this, in contrast to the old wheat-growing days: this valley is now feeding its 200,000 people in abundance, and is marketing besides, every year, food-stuffs of the value of $42,500,000. That's an annual cash income of $42.50 per acre on the cultivated land. That's an annual cash income of $212.50 for every man, woman and child in the valley, from farm products alone. That's an annual cash income of $1033.80 for every farm of the 22.000 farms of the valley. And mind: those figures represent surplus remaining after the people of the valley have used what they need for themselves. We're used to thinking of the Mississippi valley as one of the world's garden spots, vastly rich and prosperous; but please note this comparison:

Taking the five richest farming states of the Mississippi valley—Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois and Iowa—there's an BY THE POWER OF THE RIVER

The story of the Willamette valley is essentially a story for the farmer. Not that this valley hasn't some fine towns in it, strong vigorous towns, each rendering real service and all offering great opportunities to men with constructive ideas. One-fifth of the standing timber of the United States is in Oregon, within arm's reach of the Willamette valley, and in the flow of the valley's streams there's about 620,000 horse-power going to waste. Doesn't that spell opportunity?

"Oregon-pine" is a veritable household word. With railroad building and the improvement of her ports, Oregon may easily be, within twenty years, the largest producer of lumber in the Union

The farmer, like everybody else, wants variety in his life. Within plain sight, within three or four hours' reach, are the peaks of the Cascade mountains with their everlasting snow-caps

There is a great dairy farm, a model of modern dairy farming, which supplies certified milk to the city of Portland. The farm covers four hundred acres and has involved an investment of $92,000. It is paying twelve per cent net on that investment

These figures are gross, of course. Net income, though, is what counts. The net income of a farm is what remains after all cost of crop production and all cost of family maintenance are taken away from the gross income. The average Mississippi valley farmer, after paying the cost of operating his farm and keeping his family, has nothing whatever left out of his crop returns. He's been growing rich upon the increase in the value of his land, not from the profits of farming. The Oregon Agricultural College has carefully compiled actual figures covering this proposition in the Willamette valley. Here they are:

The average farm of 5 to 20 acres has a gross income of $1451, and a net income of $852; the average 20 to 80-acre farm has a gross income of $2474, and a net income of $1511; the average farm of 80 to 160 acres has a gross income of $2970 and a net income of $1762; the average farm of 160 to 320 acres has a gross income of $3487 and a net income of $1908. That shows what farming is earning for the Willamette valley farmers, in net profit, after they've paid the expense of running their farms and the cost of providing for their families, including the items of food, clothing, doctors' bills, education, and all the rest, with an allowance of $50 a year for recreation and amusement. Can you beat that?

The type of these farms is very high,and the people are uncommonly comfortable and prosperous. Anybody may see that, merely by looking out of the car windows. Prosperity is written unmistakably across the whole face of the land—in the beautiful farm homes, in the neat towns, in every sign by which prosperity is interpreted. It's a prosperity which will bear analysis, too. Bearing out Portland and the county in which Portland lies, the banks of the Willamette valley today have deposits amounting to more than 822,000,000. That's mostly farmers' money. The value of all farm property in the valley was $225,000,000 in 1910, or $10,000 to the farm. Again leaving out Portland and Multnomah

The type of these farms is very high and the people are uncommonly comfortable and prosperous.

Prosperity is written unmistakably across the face of the land-in the beautiful farm

homes, in every sign by which prosperity is interpreted

county, the valley has $3,000,000 invested in grade and high schools and is spending $1,750,000 a year for teaching and maintenance, to say nothing of what's spent on colleges and universities. That's pretty good, too, isn't it, for 200,000 people?

If you think this prosperity has been brought about by big "bonanza" farming, you're entirely wrong. The very reverse is true. You'll see that when you see how that total of $42,000,000 a year of farm products sold is made up. Here's the way it figures out:

| Dairy products | $10,000,000 |

| Poultry and eggs | 5,000,000 |

| Fruit | 4,000,000 |

| Potatoes | 6,000,000 |

| Livestock | 5,000,000 |

| Hay | 3,000,000 |

| Hops | 3,500,000 |

| Clover seed | 1,000,000 |

| Garden crops and miscellaneous | 5,000,000 |

| $42,500,000 |

You don't see wheat mentioned in that list, do you? Maybe there was some wheat in the "miscellaneous" item, along at the tail end; but it didn't cut much of a figure. A few years ago, wheat would have headed the list; but the growing and marketing of wheat has gone entirely out of fashion. Day by day the big wheat farms of the old time are being split up into farm homes; the average size of these home farms grows less and less. Just a few days ago I saw, near Salem, in the heart of the valley, a tract of 640 acres—a square mile—which had been owned and operated by a single farmer up to the year 1910. Today that tract is supporting 42 families; and every one of those 42 farmers, each with his little plot, is faring far better than the original owner fared. That's the drift of things now in the Willamette valley—toward smaller holdings, diversification, and the better use of the acre.

You'll notice that I'm making a farm story out of this. The story of the Willamette valley is essentially a story for the farmer. I've been leaving out the towns on purpose. Not that this valley hasn't some fine towns in it. There's Salem, the state capital; there's Eugene, the seat of the State University; there's Corvallis, the home of the State Agricultural College; there's Oregon City, with a commanding position at the falls of the Willamette river and a certain future in manufacturing; there are Cottage Grove, and Albany, and

The valley is now feeding its two hundred thousand people in abundance and is marketing besides, every year, foodstuffs of the value of $42,500,000; $5,000,000 of these products represent live-stock

Forest Grove, and McMinnville, and Dallas—strong, vigorous towns, each rendering real service, not to mention a dozen others; and there, at the foot of the valley, lies Portland with her quarter-million people. The story of Portland is a story by itself. Portland isn't just a Willamette valley town; Portland isn't just an Oregon town; Portland is a world-city. Sure as shooting, sure as death and taxes both put together, sure as any other sure thing on the list, Portland is to become one of the great industrial and commercial capitals of the earth.

It now contains one-third of the population of Oregon; another third is in the Willamette valley south of Portland; the other third is scattered around, up and down the coast, and in the apple valleys, and out in the wheat-growing and grazing districts.

These towns of the valley are sound as a dollar. If they have tried to "boom," the signs of it aren't in sight today. As a matter of fact, they are now organized into a sort of protective league to safeguard them selves against the evil effects of possible booming. Portland is rather taking the lead in this work. Business interests of Portland made up their mind some time ago that they didn't want their city to grow merely for the sake of being big—that they didn't want a crowding in of new citizens who would be of use only in padding out the city directory. They wanted useful men to come in, men of initiative, men whose coming would contribute to the city's real strength; but they didn't want the sort of men whose coming would mean a relaxing of the civic fiber—the speculators, the get-rich-quick artists, those eager for unearned profits. These solid business men saw clearly that their city would be bound to grow, in spite of everything; they saw too that the surest way to make that growth healthy and sound would be to look first to the development of outlying territory and to get the farming industry established on the right basis. That's what they're working at now. You'll notice that Portland isn't advertising herself at all; but she has just raised a fund of $150,000 which is to be spent in a three-year campaign of advertising the agricultural opportunities in Oregon. The Portland Commercial Club, joined in the State Development League with scores of other commercial bodies, and coöperating with the State Immigration Commission, the State Bankers' Association,

Orchard and farm in the Willamette country need not be concerned with the isolation from worth-while social life which so often makes farming irksome. Electric and steam roads network the valley and short journeys command advantages

and other strong organizations, is working hard to that end. for the extension of agricultural training in the counties, in schools and field; it is working for good roads-not great automobile highways, but systems of farmers' roads radiating from the towns into the country; it is coöperating with the farmers in organizing growers' and sellers' associations which will enable a more efficient marketing of farm products; it is working hard to suppress the land speculator, to prevent inflation of land prices, to secure the subdivision of large land holdings, and to make it possible for the immigrant farmer to get hold of a bit of land under the best possible conditions. The work has gone far, and it is going farther. Hereafter, it will be mighty hard for a boomer to find a foothold in this country. The sentiment of the people in the whole Willamette valley is dead against that sort of thing. They know what it would mean, and they don't propose to stand for it. They're bent now solely upon having the lands occupied by good farmers. If a stranger in the valley gets stung in these days by a land speculator, it's his own fault. All he need do to protect himself is to go to one of the commercial organizations, to the officers of the State Immigration Commission, or to the State Agricultural College, and he'll be in the hands of friends.

Yes, these towns are vigorous and clean and strong. They're not over-grown-not one of them. They're serving a big, useful purpose, playing their full part in the big work, steadfastly restraining all foolish ambition to outdo one another in mere mushroom growth. That's a bully good sign, don't you think? always lays an extra burden upon the surrounding country.

Don't misunderstand. I'm not saying that these towns don't want new blood, new life. They do. They offer great opportunities to men with constructive ideas. There's a wealth of raw material all around, wool, wood, leather, and all sorts of farm stuff. One-fifth of the standing timber of the United States is in Oregon, within arm's reach of the Willamette valley; and in the flow of the streams of this valley there's about 620,000 horse-power going to It is working An over-grown town Doesn't that spell opportunity? waste. But don't overlook the sign you'll find hung out in every one of these towns: "No exploiter need apply." It means just what it says. Now let me go back to the farm end of the story. That's the part that appeals to me, more than all the rest, because I'm a farmer. I'm running a farm of my own, back in Arkansas, in the Mississippi valley. I know something of what farming means, its rewards and its difficulties. Take it from me: the rewards are greater and the difficulties less in this Willamette valley than in any other place I've ever known.

The worst thing about farming is the isolation of the life, the separation of the farmer and his family from all the things that go to make up a worth-while social life. There's none of that in the Willamette valley. As I write, I'm in the heart of the valley. There's a fine network of electric and steam railways running up and down and across the land—a thousand miles of railway lines. Within half a day's travel lie the state capital, the State University, the State Agricultural College, a dozen or more higher institutions for education, and the industrial capital of the great Columbia basin. And that's not all. The farmer, like everybody else, wants variety in his life. Within plain sight, within three or four hours' reach, are the peaks of the Cascade mountains with their everlasting snow-caps; on the other side, to the west, only three or four hours away, lies the Pacific ocean; and all around, crowding one another, are hundreds of beauty spots—rivers and hills, waterfalls and caves, forests and smiling vistas—a very wonderland of beauty. Life may be very large in the Willamette valley.

On top of this, the Willamette valley has never known a crop failure.

I know well enough what's in your mind. You're wondering how much it would cost to get a foothold in this Eden. You've heard that land values are very high out here. So they are, on the face of things. But if you'll scratch below the surface you'll find that this condition isn't so bad. You may pay $400 or $50oan acre for a highly developed "going" farm if you want to; but at the State Agricultural College they'll tell you that there's still lots and lots of land to be had for $20 to $50 an acre, perfectly suited to profitable use. Land prices are very uneven over the valley; but don't let yourself be scared out by the higher figures showing here and there.

Let me tell you of two farms I've seen, at the two extremes of the scale. One is a great dairy farm, a model of modern dairy farming, supplying certified milk to the city of Portland, covering 400 acres and involving an investment of $92,000. It's paying twelve per cent. net on that investment.

The other is a farm of ten acres, about the same distance from Portland, which was tackled five years ago by a Hungarian farmer whose cash capital amounted to exactly four dollars. When he bought his land, it was in the wild woods. Today it's free of debt, supporting his family in plenty—a model of its kind too. So, you see!

I wish to goodness I were writing a book, instead of trying to tell this story in a few magazine pages. There'd be some fair chance then of saying the things that wait to be said. It's hopeless, this way. I haven't been able to crowd in a word about the golden glory of the climate, nor about the big, open-hearted, progressive spirit of the people, nor—most significant of all—about the inevitable destiny of the great Columbia basin following the opening of the Panama Canal. Maybe I'll have another chance to talk with you about those things. I hope so.

I'm going home to Arkansas now to talk to my wife about this Willamette valley country—and she's going to think that I've gone plumb crazy.