The Boy Travellers in the Russian Empire/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V.

WHEN the subject of the police was dropped by our friends, Frank asked a question about the Russian people and their origin. The Doctor answered that the topic was a broad one, as the Empire contained more than a hundred different nations and tribes of people, and that they spoke forty distinct languages. Many of the smaller tribes were assimilating with the Russians and losing their distinctiveness, even though they preserved their language; but this was by no means the case throughout the Empire.

"Not in Poland, I think," said Frank, "judging by what we saw and heard, and probably not in Finland."

"Quite right," added Doctor Bronson; "and the same is the case with the German population in the Baltic provinces. Though they have long been an integral part of the Empire, there are thousands of the inhabitants who cannot speak Russian, and refuse to teach it to their children. They are less revolutionary in their ways than the Poles, but none the less desirous of preserving their national characteristics.

"The population of Russia is about one hundred millions," he continued, "and it is spread over an area of nearly if not quite seven million square miles of land. Russia occupies about one-eighth of the land surface of the globe, but is very thinly inhabited. European Russia, including Poland, Finland, and other provinces, covers two millions of square miles, while Siberia, or European Asia, extends over at least five millions. This does not include the disputed territory of the last few years in Central Asia. It is pretty certain to come under the rule of the Emperor, and will add another half-million, if not more, to his dominions.

"The inhabitants are very unevenly distributed, as they average one hundred and twenty-seven to the square mile in Poland, and less than two to the mile in Asiatic Russia. About sixty millions belong to the Slavic race, which includes the Russians and Poles, and also a few colonies of

FINLAND PEASANTS IN HOLIDAY COSTUME.

Servians and Bulgarians, which amount in all to less than one hundred thousand. The identity of the Servians and Bulgarians with the Slavic race has been the excuse, if not the reason, for the repeated attempts of Russia to unite Servia, Bulgaria, and the other Danubian principalities with the grand Empire. The union of the Slavic people under one government has been the dream of the emperors of Russia for a long time, and what could be a better union, they argue, than their absorption into our own nation?"

Fred asked who the Slavs were, and whence they came.

"According to those who have studied the subject," Doctor Bronson answered, "they were anciently known as Scythians or Sarmatians. Their

INHABITANTS OF SOUTHERN RUSSIA.

early history is much obscured, but they seem to have had their centre around the Carpathian Mountains, whence they spread to the four points of the compass. On the north they reached to the Baltic; westward, they went to the banks of the Elbe; southward, beyond the Danube; and eastward, their progress was impeded by the Tartar hordes of Asia, and they did not penetrate far into Siberia until comparatively recent times. With their extension they split up into numerous tribes and independent organizations; thus their unity was lost, and they took the form in which we find them to-day. Poles and Russians are both of the same race, and their languages have a common origin; but nowhere in the world can be found two people who hate each other more heartily. However much the Russians have favored a Pan-Slavist union, you may be sure the Poles look on it with disfavor.

"The ancient Slavonic language has given way to the modern forms in the same way that Latin has made way for French, Italian, Spanish,

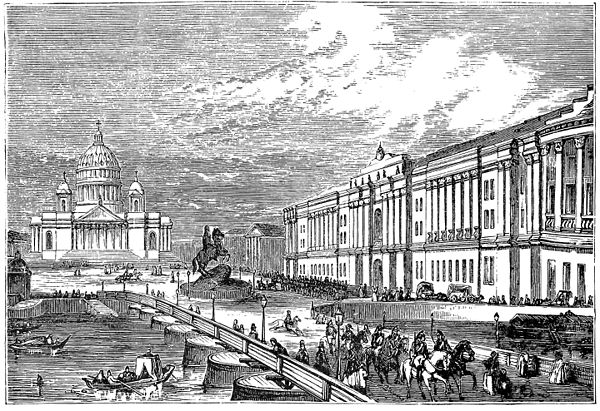

ST. ISAAC'S CHURCH AND ADMIRALITY SQUARE

and other tongues and dialects with a Latin origin. In fact those languages hold the same relation to Latin that Polish, Russian, Servian, and Bulgarian hold towards ancient Slavonic. The Romish Church uses Latin in its service, and the Russo-Greek Church uses the old Slavonic; the Poles, Bohemians, and others have adopted the Roman alphabet, but the Russians use the Slavonic characters in a modified form. The Russian alphabet has thirty-six letters, some being Roman, others Greek, and others Slavonic. After you have learned the alphabet and can spell out the signs on the shops and street corners, I'll tell you more about the language."

It was getting late, and the party broke up a few minutes after the foregoing conversation. Before they separated, Doctor Bronson suggested to the youths that he should expect them to read up the history of Russia, and not forget the Romanoff family. "The Romanoffs," said he, "are the reigning family of Russia, just as the Guelphs are of England and the Hapsburgs of Austria."

It was speedily arranged that Frank would devote special attention to the first-named subject, while Fred would assume the responsibilities of the latter. "And while you are on the subject," the Doctor added, turning to Fred, "see if you can find about the origin of the Orloff family, which is one of the most interesting traditions that has been handed down." Fred promised, and the party separated for the night.

They were all up in good season the next morning, and after a substantial breakfast, in which the samovar had a prominent place, they set out for a round of sight-seeing in the modern capital of Russia.

Returning to Admiralty Square, they visited the Church of St. Isaac, accompanied by the guide they had engaged at the hotel. The man was of Russian birth, and spoke English with considerable fluency. Evidently he understood his business, as he told the history of the sacred edifice with a careful adherence to dates.

"Peter the Great built a wooden church on this very spot," said the guide, "in 1710, but it was destroyed by fire. Afterwards the great Catherine erected another, which was finished in 1801; but it only remained eighteen years. The present building was begun in 1819, and its completion took nearly forty years. It was consecrated in 1858, and is considered the finest church in the Empire."

"The last statement might be disputed by some of the citizens of Moscow," said the Doctor to the youths, "but there is no question about the church being the finest in St. Petersburg. Observe its admirable proportions," he continued. "It is in the form of a Greek cross, with its four sides of equal length, and the architect who planned it certainly had a correct eye for his work."

"You observe," said the guide, "that each of the four entrances is approached by three flights of stone steps, leading up from the level of the square. Each of these flights of steps is cut from a single block of Finland granite."

The youths made note of this fact as they wondered how the huge masses of stone were brought from their quarries; and they also noted that the four entrances of the church were between pillars of granite sixty feet high and seven feet in diameter, polished to the smoothness of a mirror. An immense dome forms the centre of the edifice. It is of iron, covered on the outside with copper, and this copper is heavily plated with

PRIEST OF THE CHURCH OF ST. ISAAC.

pure gold. It is the dome which first caught the eyes of the travellers as they approached the city, and forms an important landmark from every direction. The cupola rests on thirty granite pillars, which look small enough when seen from below, but are really of great size.

In the inside of the church are paintings by Russian artists, and there are two columns of malachite fifty feet high, and of proportionate diameter—the largest columns of this costly mineral anywhere in the world. Immense quantities of malachite, lapis-lazuli, and other valuable stones are used in the decoration of the church, and our friends thought that if there was anything to criticise it was the great amount of ornamentation and gilding in the interior. "But I have no doubt," wrote Fred in his notebook, "that this display has its effect upon the worshippers in the church, and particularly among the poor peasants and all others of the humbler classes. In all the countries we have visited, whether of the Christian, Moslem, Buddhist, or other faith, we have found the religious edifices adorned in the most costly manner, and there is no reason why Russia should form an exception to the general rule. Many of the paintings, columns, and others decorations of this church were the gift of wealthy Russians, while others were paid for by the contributions of the people, or from the funds in Government hands."

CATHERINE II. OF RUSSIA.

From the Church of St. Isaac our friends went to the Hermitage and the Winter Palace, the latter being named in contradistinction to the Summer Palace, which is at Tsarskoe-Selo, a few miles from the capital. We will see what the youths had to say of their visit to these edifices. Fred will tell the story.

"To describe all we saw there would take a fair-sized volume," said Fred, "and we will only tell what impressed us most. The palace was built in a great hurry, to take the place of the one that was burned in 1837. It was ready for occupation in 1839; and when you know that it is four hundred and fifty feet long by three hundred and fifty wide, and rises to a height of eighty feet, you will agree with us that the Russians are to be praised for their energy. Our guide had procured the necessary ticket for admittance, and we passed in through an enormous gateway opposite the Column of Alexander. Two servants in livery showed us through the halls and galleries, and for hours we wandered among pictures which represent the victories of Russia over its enemies, and amid costly furniture and adornments, till our feet and eyes were weary. The Throne-room of Peter the Great is one of the finest of the apartments, and the Hall of St. George is the largest. It measures one hundred and forty feet by sixty, and is the scene of the grand balls and receptions which the Emperor gives on state occasions. There is a beautiful apartment, known as the drawing-room of the Empress. Its walls and ceiling are gilded, and the whole work about it seems to have been done without regard to expense.

"One of the halls contains portraits of the rulers of Russia from Peter the Great down to the present time; another, the portraits of the generals who fought against the French in 1812; another, the portraits of all the field-marshals of the armies by which Napoleon was conquered; and others, the battle-scenes before mentioned. I observed that Russia was not unlike France, Germany, and other countries in representing very prominently the battles where she triumphed, and ignoring those where she was defeated. The guide told us that at the state balls in the palace sit-down suppers are provided for all the guests, even if there are two or three thousand of them. Sometimes the supper-hall is converted into a garden by means of trees brought from greenhouses. The guests sit at table beneath the foliage, and can easily forget that they are in the middle of a Russian winter.

"Doctor Bronson says the Russians are very fond of plants in their dwellings, the wealthy expending large sums on greenhouses and conservatories, and the poorer people indulging in flower-pots, which they place in all available spots. The wealthy frequently pay enormous prices for rare exotics. We have seen a good many flower-stores along the Nevski Prospect and in other streets, and are ready to believe that the Russians are great admirers of floral products. Their long, cold, and cheerless winters lead them to prize anything that can remind them of the summer season.

"At the entrance of one of the halls there is a tablet on which are the rules which Catherine II. established for the informal parties she used to have at the Hermitage. Catherine had literary aspirations, and her parties were in imitation of the salons of Paris, which have a wide celebrity. Here is a translation of the rules, which I take from Murray's 'Handbook:'

"'1. Leave your rank outside, as well as your hat, and especially your sword.

"'2. Leave your right of precedence, your pride, and any similar feeling, outside the door.

"'3. Be gay, but do not spoil anything; do not break or gnaw anything.

"'4. Sit, stand, walk as you will, without reference to anybody.

"'5. Talk moderately and not very loud, so as not to make the ears and heads of others ache.

"'6. Argue without anger and without excitement.

"'7. Neither sigh nor yawn, nor make anybody dull or heavy.

"'8. In all innocent games, whatever one proposes, let all join.

"'9. Eat whatever is sweet and savory, but drink with moderation, so that each may find his legs on leaving the room.

RECEPTION OF JOHN PAUL JONES BY THE EMPRESS CATHERINE.

"'10. Tell no tales out of school; whatever goes in at one ear must go out at the other before leaving the room.

"'A transgressor against these rules shall, on the testimony of two witnesses, for every offence drink a glass of cold water, not excepting the ladies, and further read a page of the "Telemachiade" aloud.

"'Whoever breaks any three of these rules during the same evening shall commit six lines of the "Telemachiade" to memory.

"'And whoever offends against the tenth rule shall not again be admitted.'

"The 'Telemachiade' which is prescribed as a penance was the work of a Russian poet of Catherine's time, who does not seem to have enjoyed the Imperial favor. It is said that invitations to these parties were much sought; but, in spite of all her efforts, the Empress could not induce her guests to forget entirely that she was their sovereign. However, she managed to make her parties much less formal than anything ever known before at the Imperial Palace, and this was a great deal to accomplish in such a time and in such a country.

"I may remark, by-the-way, that the Empress Catherine was the first sovereign of Russia to invite an American officer into the Imperial service. That officer was the celebrated John Paul Jones, a Scotchman by birth but an American citizen at the time of the Revolutionary war. The havoc he wrought upon the British fleets attracted the attention of the Russian Government, and after our war was over he received an intimation that he could find employment with the armies of the Empress. He went to St. Petersburg, was received by Catherine at a special audience, and accorded the rank of admiral in the Imperial Navy. Russia was then at war with Turkey. Admiral Jones was sent to command the Russian fleet in the Black Sea, and operate against the Turkish fleet, which he did in his old way.

"The Russians were besieging a town which was held by the Turks, who had a fleet of ships supporting their land-forces. Jones dashed in among the Turkish vessels with a boarding-party in small boats, backed by the guns of his ships and those of the besieging army. He captured two of the Turkish galleys, one of them belonging to the commander of the fleet, and made such havoc among the enemy that the latter was thoroughly frightened. Unfortunately, Jones incurred the displeasure of Potemkin, the Prime-minister, and favorite of the Empress, and shortly after the defeat of the fleet he was removed from command and sent to the Baltic, where there was no enemy to operate against.

"But I am neglecting the palace in following the career of an American in the service of Russia."We asked to see the crown jewels of Russia, and the guide took us to the room where they are kept. One of the most famous diamonds of the world, the Orloff, is among them, and its history is mixed up with a good deal of fable. The most authentic story about this diamond seems

RUSSIAN ATTACK ON THE TURKISH GALLEY.

to be that it formed the eye of an idol in a temple in India, whence it was stolen by a French soldier, who sold it for two thousand guineas. It then came to Europe, and after changing hands several times was bought by Prince Orloff, who presented it to the Empress Catherine. The Prince is said to have given for the diamond four hundred and fifty thousand rubles (about four hundred thousand dollars), a life annuity of two thousand rubles, and a patent of nobility. It weighs more than the famous Koh-i-noor of England, but is not as fine a stone. There is a faint tinge of yellow that depreciates it considerably, and there is also a flaw in the interior of the stone, though only perceptible on a careful examination.

THE ORLOFF DIAMOND.

"The Imperial crown of Russia is the most interesting crown we have anywhere seen. The guide told us how much it was worth in money, but I've forgotten, the figures being so large that my head wouldn't contain them. There are rubies, diamonds, and pearls in great profusion, the diamonds alone being among the most beautiful in the world. There are nearly, if not quite, a hundred large diamonds in the crown, not to mention the smaller ones that fill the spaces where large ones could not go. The coronet of the Empress is another mass of precious stones worth a long journey to see. There are other jewels here of great value, among them a plume or aigrette, which was presented to General Suwarroff by the Sultan of Turkey. It is covered with diamonds mounted on wires that bend with each movement of the wearer. What a sensation Suwarroff must have made when he walked or rode with this plume in his hat!

"From the crown jewels we went to a room whose history is connected with a scene of sadness—the death of the Emperor Nicholas. It is the smallest and plainest room of the palace, without any adornment, and containing an iron bedstead such as we find in a military barrack. His cloak, sword, and helmet are where he left them, and on the table is the report of the quartermaster of the household troops, which had been delivered to the Emperor on the morning of March 2, 1855, the date of his death. Everything is just as he left it, and a soldier of the Grenadier Guards is constantly on duty over the relics of the Iron Czar.

"If what we read of him is true, he possessed one characteristic of Peter the Great—that of having his own way, more than any other Emperor of modern times. He ascended the throne in the midst of a revolution which resulted in the defeat of the insurgents. They assembled in Admiralty Square, and after a brief resistance were fired upon by the loyal soldiers of the Empire. Five of the principal conspirators were hanged after a long and searching trial, during which Nicholas was concealed behind a screen in the court-room, and listened to all that was said.

Two hundred of the others were sent to Siberia for life, and the soldiers who had simply obeyed the orders of their leaders were distributed among other regiments than those in which they had served.

"Through his whole reign Nicholas was an enemy to free speech or free writing, and his rule was severe to the last degree. What he ordered it was necessary to perform, no matter what the difficulties were in the way, and a failure was, in his eyes, little short of a crime. He decided questions very rapidly, and often with a lack of common-sense. When the engineers showed him the plans of the Moscow and St. Petersburg Railway, and asked where the line should run, he took a ruler, drew on the map a line from one city to the other, and said that should be the route. As a consequence, the railway is very nearly straight for the whole four hundred miles of its course, and does not pass any large towns like the railways in other countries.

NICHOLAS I.

"A more sensible anecdote about him relates an incident of the Crimean war, when the Governor of Moscow ordered the pastor of the English Church in that city to omit the portion of the service which prays for the success of British arms. The pastor appealed the case to the Emperor, who asked if those words were in the regular service of the English Church. On being answered in the affirmative, he told the pastor to continue to read the service just as it was, and ordered the governor to make no further interference.

"His disappointment at the defeat of his armies in the Crimean war was the cause of his death, quite as much as the influenza to which it is attributed. On the morning of his last day he received news of the repulse of the Russians at Eupatoria, and he is said to have died while in a fit of anger over this reverse. Though opposed to the freedom of the Press and people, he advised the liberation of the serfs; and before he died he urged his son and successor to begin immediately the work of emancipation.

"The Hermitage is close to the palace, and is large enough of itself for the residence of an emperor of medium importance, and certainly for a good-sized king. The present building is the successor of one which was built for the Empress Catherine as a refuge from the cares of State, and hence was called the Hermitage. It is virtually a picture-gallery and

PETER III.

museum, as the walls of the interior are covered with pictures, and there are collections of coins, gems, Egyptian antiquities, and other things distributed through the rooms.

"The room of greatest interest to us in the Hermitage was that containing the relics of Peter the Great. There were the turning-lathes whereon he worked, the knives and chisels with which he carved wood into various forms, together with specimens of his wood-carving. His telescopes, drawing-instruments, walking-stick, saddle, and other things are all here, and in the centre of the room is an effigy which shows him to have been a man of giant stature, as does also a wooden rod which is said to be the one with which he was actually measured. There is a carriage in which he drove about the city, the horse he rode at the battle of Pultowa, and several of his favorite dogs, all stuffed and preserved, but not in the highest style of the taxidermist. There are casts taken after Peter's death, several portraits in oil and one in mosaic, and a cast taken during life, and presented by Peter to his friend Cardinal Yalenti at Rome. It was missing for a long time, but was finally discovered about the middle of this century by a patriotic Russian, who bought it and presented it to the gallery.

"There is a clock in the same room which is said to have contained at one time the draft of a constitution which Catherine the Great intended giving to her people. Immediately after her death her son and successor, Paul, rushed to the clock in her bedroom, drew out the paper, and destroyed it. At least this is the tradition; and whether true or not, it is worth knowing, as it illustrates the character of Paul I."

CIRCASSIAN ARMS AS TROPHIES OF BATTLE.

Our friends imitated the course of many an Imperial favorite, not only in Russia, but in other countries, by going from a palace to a prison, but with the difference in their case that the step was voluntary.

As they crossed the bridge leading from the Winter Palace in the direction of the grim fortress of Sts. Peter and Paul, Doctor Bronson told the youths that Peter the Great shut up his sister in a convent and exiled her minister, Prince Galitzin. "Since his time," the Doctor continued, "his example has been followed by nearly every sovereign of Russia, and a great many persons, men and women, have ended their lives in prison or in exile who once stood high in favor at the Imperial court. Catherine was accustomed to dispose of the friends of whom she had wearied by sending them to live amid Siberian snows, and the Emperor Paul used to condemn people to prison or to exile on the merest caprice. Even at the present day the old custom is not unknown."

"We were not admitted to the cells of the fortress," said Frank, in his account of the visit to the place, "as it was 'contrary to orders,' according to the guide's explanation. But we were shown through the cathedral where the rulers of Russia from the time of Peter the Great have been buried, with the exception of Peter II., who was buried at Moscow, where he died. The tombs are less elaborate than we expected to find them, and the walls of the church are hung profusely with flags, weapons of war, and other trophies of battle. The tombs mark the positions of the graves, which are beneath the floor of the cathedral. Naturally the tombs that most attracted our attention were those of the rulers who have been most famous in the history of Russia.

STATUE OF NICHOLAS I.

"We looked first at the burial-place of the great Peter, then at that of Catherine II., and afterwards at the tomb of Nicholas I.; then we sought the tomb of Alexander II., who fell at the hands of Nihilist assassins, and after a brief stay in the church returned to the open air. The building is more interesting for its associations than for the artistic merit of its interior. Its spire is the tallest in the Empire, with the exception of the tower of the church at Revel, on the Baltic coast. From the level of the ground to the top of the cross is three hundred and eighty-seven feet, which is twenty-six feet higher than St. Paul's in London.

"The spire alone is one hundred and twenty-eight feet high, and very slender in shape. It was erected more than a hundred years ago, and the church itself dates almost from the time of the foundation of the city. Fifty or more years ago the angel and cross on the top of the spire threatened to fall, and a Russian peasant offered to repair them for two hundred rubles. By means of a rope and a few nails, he climbed to the top of the spire and performed the work, and nobody will say he did not earn his money. A single misstep, or the slightest accident, would have dashed him to certain death.

"When we left the church and fortress," continued Frank, "we felt that we had had enough for the day of that kind of sight-seeing, so we drove through some of the principal streets and went to the Gostinna Dvor, where we wished to see the curiosities of the place and make a few purchases.

"Near St. Isaac's Church we passed the famous equestrian statue of the Emperor Nicholas, in which the sculptor succeeded in balancing the horse on his hind feet without utilizing the tail, as was done in the case of the statue of Peter the Great. The Emperor is in the uniform of the Horse Guards. The pedestal is formed of blocks of granite of different colors, and there are bronze reliefs on the four sides representing incidents in the Emperor's life and career. On the upper part of the pedestal at each of the corners are emblematical figures, and just beneath the forefeet of the horse is a fine representation of the Imperial eagle. The whole work is surrounded with an iron fence to preserve it from injury, and altogether the statue is one of which the city may well be proud."

While the party were looking at the Imperial arms just mentioned, Fred asked why the eagle of Russia is represented with two heads.

"It indicates the union of the Eastern and Western empires," the Doctor answered, "the same as does the double-headed eagle of Austria. The device was adopted about four centuries ago by Ivan III., after his marriage with Sophia, a princess of the Imperial blood of Constantinople.

"By-the-way," the Doctor continued, "there's a story of an Imperial grand-duke who went one day on a hunting excursion, the first of his life, and fired at a large bird which rose before him. The bird fell, and was brought by a courtier to the noble hunter.

"'Your Imperial Highness has killed an eagle,' said the courtier, bowing low and depositing the prey on the ground.

"The grand-duke looked the bird over carefully, and then turned away with disdain. 'That's no eagle,' said he, 'it has only one head.'"

What our young friends saw in the Gostinna Dvor will be told in the next chapter.