The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1729)/Book 1/Section 12

Section XII.

Of the attractive forces of sphærical bodies.

Proposition LXX. Theorem XXX.

If to every point of a sphærical surface there tend equal centripetal forces decreasing in the duplicate ratio of the disstances from those points; I say that a corpuscle placed within that superficies will not be attracted by those forces any way.

Let HIKL (Pl. 21. Fig. 4.) be that sphærical superficies, and P a corpuscle placed within. Through P let there be drawn to this superficies the two lines HK, IL, intercepting very small arcs HI, KL; and because (by cor. 3. lem. 7.) the triangles HPI, LPK are alike, those arcs will be proportional to the distances HP, LP; and any particles at HI and KL of the sphærical superficies, terminated by right lines passing through P, will be in the duplicate ratio of those distances. Therefore the forces of these particles exerted upon the body P are equal between themselves. For the forces are as the particles directly and the squares of the distances inversely. And these two ratio's compose the ratio of equality. The attractions therefore being made equally towards contrary parts destroy each other. And by a like reasoning all the attractions through the whole sphærical superficies are destroyed by contrary attractions. Therefore the body P will not be any way impelled by those attractions. Q. E. D.

Proposition LXXI. Theorem XXXI.

The same things supposed as above, I say that a corpuscle placed without the sphærical superficies is attracted towards the centre of the sphere with a force reciprocally proportional to the square of its distance from that centre.

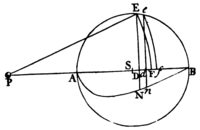

Let AHKB, ahkb (Pl. 21. Fig. 5.) be two equal sphærical superficies described about the centres S, s; their diameters AB, ab; and let P and p be two corpuscles situate without the spheres in those diameters produced. Let there be drawn from the corpuscles the lines PHK, PIL, phk, pil, cutting off from the great circles AHB, ahb, the equal arcs HK, bk, IL, il; and to those lines let fall the perpendiculars SD, sd, SE, se, IR, ir; of which let SD, sd cut PL, pl in F and f. Let fall also to the diameters the perpendiculars IQ, iq. Let now the angles DPE, dpe vanish; and because DS and ds, ES and es are equal, the lines PE, PF, and pe, pf, and the lineolæ DF, df may be taken for equal; because their last ratio, when the angles DPE, dpe vanish together, is the ratio of equality. These things then supposed, it will be, as PI to PF so is RI to DF, and, as pf to pi so is df or DF to ri; and ex æquo, as PI x pf to PF x pi so is RI to ri, that is (by cor. 3. lem. 7.) so is the arc IH to the arc ih. Again PI is to PS as IQ to SE, and ps ro pi as se or SE to iq; and ex æquo PI x ps to PS x pi as IQ to iq. And compounding the ratio's is to , as IH x IQ to ib x iq; that is, as the circular superficies which is described by the arc IH as the semicircle AKB revolves about the diameter AB, is to the circular superficies described by the arch ih as the semicircle akb revolves about the diameter ab. And the forces with which these superficies attracts the corpuscles P and p in the direction of lines tending to those superficies are by the hypothesis as the superficies themselves directly, and the squares of the distances of the superficies from those corpuscles inversely; that is, as pf x ps to PF x PS. And these forces again are to the oblique parts of them which (by the revolution of forces as in cor. 2. of the laws) tend to the centres in the directions of the lines PS, ps, as PI to PQ and pi to pq; that is (because of the like triangles PIQ and PSF, piq and psf) as PS to PF and ps to pf. Thence ex equo, the attraction of the corpuscle P towards S is to the attraction of the corpuscle p towards s, as is to , that is, as to . And by a like reasoning the forces with which the superficies described by the revolution of the arcs KL, klattract those corpuscles, will be as to . And in the same ratio will be the forces of all the circular superficies into which each of the sphærical superficies may be divided by taking sd always equal to SD, and se equal to SE. And therefore by composition, the forces of the entire sphærical superficies exerted upon those corpuscles will be it: the same ratio. Q. E. D.

Proposition LXXII. Theorem XXXII.

If to the sveral points: of a sphere there tend equal centripetal forces decreasing in a duplicate ratio of the distances from those points; and there be given both the density of the sphere and the ratio of the diameter of the sphere to the distance of the corpuscle from its centre; I say that the force with which the corpuscle is attracted is proportional to the semi-diameter of the sphere.

For conceive two corpuscles to be severally attracted by two spheres, one by one the other by the other, and their distances from the centres of the spheres to be proportional to the diameters of the spheres respectively; and the spheres to be resolved into like particles disposed in a like situation to the corpuscles. Then the attractions of one corpuscle towards the several particles of one sphere, will be to the attractions of the other towards as many analogous particles of the other sphere in a ratio compounded of the ratio of the particles directly and the duplicate ratio, of the disŧances inversely. But the particles are as the spheres, that is in a triplicate ratio of the diameters, and the distances are as the diameters; and the first ratio directly with the last ratio taken twice inversely, becomes the ratio of diameter to diameter. Q. E. D.

Cor. 1. Hence if corpuscles revolve in circles about spheres composed of matter equally attracting; and the distances from the centres of the spheres be proportional to their diameters; the periodic times will be equal.

Cor. 2. And vice versa, if the periodic times are equal, the distances will be proportional to the diameters. These two corollaries appear from cor. 5. prop. 4.

Cor. 3. If to the several points of any two solids whatever, of like figure and equal density, there tend equal centripetal forces decreasing in a duplicate ratio of the distances from those points; the forces with which corpuscles placed in a like situation to those two solids, will be attracted by them will be to each other as the diameters of the solids.

Proposition LXXIII. Theorem XXXIII.

If to the sevaral points of a given sphere there tend equal centripetal forces decreasing in a duplicate ratio of the disŧances from the points; I say that a corpuscle placed within sphere is attracted by a force proportional to its disŧance from the centre.

In the sphere ABCD (Pl. 21. Fig. 6.) described about the centre S, let there be placed the corpuscle P; and about the same centre S, with the interval SP, conceive described an interior sphere PEQF. It is plain (by prop. 70.) that the concentric sphærical supericies of which the difference AEBF of the spheres is composed, have no effect at all upon the body P; their attractions being destroyed by contrary attractions. There remains therefore only the attraction of the interior sphere PEQF And (by prop. 72.) this is as the distance PS. Q. E. D.

Scholium

By the superficies of which I here imagine the solidg composed, I do not mean superficies purely mathematical, but orbs so extreamly thin, that their thickness is as nothing; that is, the evanescent orbs; of which the sphere will at last consist, when the number of the orbs is increased, and their thickness diminished without end. In like manner, by the points of which lines, surfaces and solids are said to be composed, are to be understood equal particles whose magnitude is perfectly incossiderable.

Proposition LXXIV. Theorem XXXIV.

The same things supposed, I say that a corpuscle situate without a force reciprocally proportional to the square of its distance form the centre.

For suppose the sphere to be divided into innumerable concentric sphærical superficies, and the attractions of the corpuscle arising from the several superficies will be reciprocally proportional to the square of the distance of the corpuscle from the centre of the sphere (by prop. 71.) And by composition, the sum of those attractions, that is, the attraction of the corpuscle towards the entire sphere, will be in the same ratio. Q. E. D.

Cor. 1. Hence the attractions of homogeneous spheres at equal distances from the centres will be as the spheres themselves. For (by prop. 72.) if the distances be proportional to the diameters of the spheres, the forces will be as the diameters. Let the greater distance be diminished in that ratio; and the distances now being equal, the attraction will be increased in the duplicate of that ratio; and therefore will be to the other attraction in the triplicate of that ratio; that is, in the ratio of the spheres.

Cor. 2. At any distances whatever; the attractions are as the spheres applied to the squares of the distances.

Cor. 3. If a corpuscle placed without an homogeneous sphere is attracted by a force reciprocally proportional to the square of its distance from the centre, and the sphere consists of attractive particles; the force of every particle will decrease in a duplicate ratio of the distance from each particle.

Proposition LXXV. Theorem XXXV.

If to the several points of a given sphere there tend equal centripetal force; decresing in a duplicate ratio of the distances from the points; I say that another similar sphere will be attracted by it with a force reciprocal proportional to the square of the disŧance of the centres.

For the attraction of every particle is reciprocally as the square of its distance from the centre of the attracting sphere (by prop. 74.) and is therefore the same as if that whole attracting force issued from one single corpuscle placed in the centre of this sphere. But this attraction is as great, as on the other hand the attraction of the same corpuscle would be, if that were it self attracted by the several particles of the attracted sphere with the same force with which they are attracted by it. But that attraction of the corpuscle would be (by prop. 74.) reciprocally proportional to the square of its distance from the centre of the sphere; therefore the attraction of the sphere, equal thereto, is also in the same ratio. Q. E. D.

Cor. 1. The attractions of spheres towards other homogeneous spheres, are as the attracting spheres applied to the squares of the distances of their centres from the centres of those which they attract.

Cor. 2.. The case is the same when the attracted sphere does also attract. For the several points of the one attract the several points of the other with the same force with which they themselves are attracted by the others again; and therefore since in all attractions (by law 3.) the attracted and attracting point are both equally acted on, the force will be doubled by their mutual attractions, the proportions remaining.

Cor. 3. Those several truths demonstrated above concerning the motion of bodies about the focus of the conic sections, will take place when an attracting sphere is placed in the focus, and the bodies move without the sphere.

Cor. 4. Those things which were demonstrated

before of the motion of bodies about the centre of the

conic sections take place when the motions are performed

within the sphere.

Proposition LXXVI. Theorem XXXVI.

If spheres be however dissimilar (as to density of matter and attractive force) in the progress right onward from the centre to the circumference; but every where similar, at every given disŧance from the centre, on all sides round about; and the attractive force of every point decreases in the duplicate ratio of the distance of the body attracted; I say that the whole force with which one of these spheres attracts the other, will be reciprocally proportional to the force of the distance of the centres.

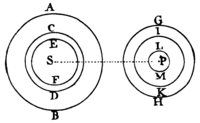

Imagine several concentric similar spheres, AB, CD, EF, &c. (Pl. 22. Fig. 1.) the innermost of which added to the outermost may compose a matter more dense towards the centre, or subducted from them may leave the same more lax and rare. Then by prop. 75. these spheres will attract other similar concentric spheres GH, IK, LM, &c, each the other, with forces reciprocally proportional to the square of the distance SP. And by composition or division, the sum of all those forces, or the excess of any of them above the others; that is, the entire force with which the whole sphere AB (composed of an concentric spheres or of their differences) will attract the whole sphere GH (composed of any concentric spheres or their differences) in the same ratio. Let the number of the concentric spheres be increased in infinitum, so that the density of the matter together with the attractive force may, in the progress from the circumference to the centre, increase or decrease according to any given law; and by the addition of matter not attractive let the deficient density be supplied that so the spheres may acquire any form desired; and the force with which one of these attracts the other, will be still, by the former reasoning, in the same ratio of the square of the distance inversely. Q. E. D.

Cor. 1. Hence if many spheres of this kind, similar in all respects, attract each other mutually; the accelerative attractions of each to each, at any equal distances of the centres, will be as the attracting spheres.

Cor. 2. And at any unequal distances, as the attracting spheres applied to the squares of the distances between the centres.

Cor. 3. The motive attractions, or the weights of the spheres towards one another will be at equal distances of the centres as the attracting and attracted spheres conjunctly; that is, as the products arising from multiplying the spheres into each other.

Cor. 4. And at unequal distances, as those products directly and the squares of the distances between the centres inversely.

Cor. 5. These proportions take place also, when the attraction arises from the attractive virtue of both spheres mutually exerted upon each other. For the attraction is only doubled by the conjunction of the forces, the proportions remaining as before.

Cor. 6. If spheres of this kind revolve about others at rest, each about each; and the distances between the centres of the quiescent and revolving bodies are proportional to the diameters of the quiescent bodies; the periodic times will be equal.

Cor. 7. And again, if the periodic times are equal, the distances will be proportional to the diameters.

Cor. 8. All those truths above demonstrated, relating to the motions of bodies about the foci of conic sections, will take place, when an attracting sphere, of any form and condition like that above described, is placed in the focus.

Cor. 9. 9. And also when the revolving bodies are also attracting spheres of any condition like that above described.

Proposition LXXVII. Theorem XXVIII.

If to the several points of spheres there tend centripetal forces proportional to the disŧances of the points from the attracted bodies; I say that the compounded force with which two spheres attract each other mutually is or the disŧance between the centres of the spberes.

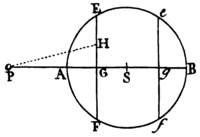

Case 1. Let AEBF (Pl. 22. Fig. 2.) be a sphere; S its centre; P a corpuscle attracted; PASB the axis of the sphere pulling through the centre of the corpuscle; EF, ef two planes cutting the sphere, and perpendicular to the axis, and equidistant, one on one side, the other on the other, from the centre of the sphere; G and g the intersections of the planes and the axis; and H any point in the plane EF. The centripetal force of the point H upon the corpuscle P, exerted in the direction of the line PH is as the distance PH; and (by cor. 2. of the laws) the same exerted in the direction of the line PG, or towards the centre S, is at the length PG. Therefore the force of all the points in the plane EF (that is of that whole plane) by which the corpuscle P is attracted towards the centre S is as the distance PG multiplied by the number of those points, that is as the solid contained under that plane EF and the distance PG. And in like manner the force of the plane ef by which the corpuscle P is attracted towards the centre S, is as at plane drawn into its distance Pg, or as the equal plane EF drawn into that distance P; and the sum of the forces of both planes as are plane EF drawn into the sum of the distances PG + Pg, that is as that plane drawn into twice the distance PS of the centre and the corpuscle; that is, as twice the plane EF drawn into the distance PS, or as the sum of the equal planes EF + ef drawn into the same distance. And by a like reasoning the forces of all the planes in the whole sphere, equidistant on each side from the centre of the sphere, are as the sum of those planes drawn into the distance PS, that is, as the whole sphere and the disŧance PS conjunctly. Q. E. D.

Case 2. Let now the corpuscle P attract the sphere

AEBF. And by the same reasoning it will appear

that the force with which the sphere is attracted is as

the distance PS. Q. E. D.

Case 3. Imagine another sphere composed of innumerable corpuscles P; and because the force with which every corpuscle is attracted is as the distance of the corpuscle from the centre of the first sphere, and as the same sphere conjunctly, and is therefore the same as if it all proceeded from a single corpuscle situate in the centre of the sphere; the entire force with which all the corpuscles in the second sphere are attracted, that is, with which that whole sphere is attracted, will be the same as if that sphere were attracted by a force issuing from a single corpuscle in the centre of the first sphere; and is therefore proportional to the distance between the centres of the spheres. Q. E. D.

Case 4. Let the spheres attract each other mutually, and the force will be doubled. but the proportion will remain. Q. E. D.

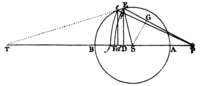

Case 5. Let the corpuscle be placed within the

sphere AEBF; (Fig. 3.) and because the force of the

plane ef upon the corpuscle is as the solid contained

under that plane and the distance pg; and the contrary

force of the plane EF as the solid contained

under that plane and the distance pG; the force

compounded of both will be as the difference of

the solids, that is as the sum of the equal planes

drawn into half the difference of the distance that

is, as that sum drawn into PS, the distance

of the corpuscle from the centre of the sphere.

And by a like reasoning, the attraction of all the

planes EF, ef throughout the whole sphere, that

is, the attraction of the whole sphere, is conjunctly

as the sum of all the planes, or as the whole spheres

and as pS, the distance of the corpuscle from the

centre of the sphere. Q. E. D.

Case 6. And if there be composed a new sphere out of innumerable corpuscles such as p, situate within the first sphere AEBF; it may be proved as before that the attraction whether, single of one sphere towards the other, or mutual of both towards each other, will be as the distance pS of the centres. Q. E. D.

Proposition LXXVIII. Theorem XXVIII.

If spheres in the progression from the centre to the circumference be however dissimimar and unequable, but similar on every side round about at all given disŧances from the centre; and the attractive force of every point be as the disŧance of the attracted body; I say that the entire force with which two spheres of this kind attract each other mutually is proportional to the centres of the spheres.

This is demonstrated from the foregoing proposition in the same manner as the 76th proposition was demonstrated from the 75th

Cor. Those things that were above demonstrated in prop. 10. and 64. of the motion of bodies round the centres of conic sections, take place when all the attractions are made by the force of sphærical bodies of the condition above described, and the attracted bodies are spheres of the same kind.

Scholium.

I have now explained the two principal case of attractions; to wit, when the centripetal forces decrease in a duplicate ratio of the distances, or increase in a simple ratio of the distances; causing the bodies in both cases to revolve in conic sections, and composing sphærical bodies whose centripetal forces observe the same law of increase or decrease in the recess from the centre as the forces of the particles themselves do; which is very remarkable. It would be tedious to run over the other cases, whose conclusions are less elegant and important, so particularly as I have done these. I chuse rather to comprehend and determine them all by one general method as follows.

Lemma XXIX.

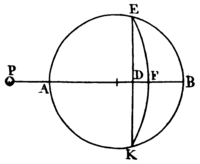

If about the centre S (Pl. 22. Fig. 4.) these le described arty circle at AEB, and about the centre P there be also described two circles EF, ef, cutting the first in R and e, and the line PS in F and f; and the line PS in F and f; and there be let fall to PS the perpendiculars ED, ed; I say, that, if the disŧance of the arcs EF, ef, be supposed to be infinitely, the last ratio of the evanescent evanescent line Dd to the evanescent line Ff is the same as that of the line PE to the line PS.

For if the line Pe cut the arc EF in q; and the right line Ee, which coincides with the evanescent arc Ee, be produced and meet the right line PS in T; and there be let fall from S to PE the perpendicular SG; then because of the like triangles DTE, dTe, DES; it will be as Dd to Ee so DT to TE, or DE to ES; and because the triangles Eeq, ESG (by lem. 8. and cor. 3. lem. 7.) are similar, it will be as Ee to eq or Ff so ES to SG; and ex æquo, as Dd to Ff so DE to SG; that is (because is the similar triangles PDE, PGS) so is PE to PS. Q. E. D.

Proposition LXXIX. Theorem XXXIX.

Suposse a superficies as EFfe (Pl. 22 Fig. 5.) to have its breadth infinitely diminished, and to be just vanishing; and that the same superficies by its revolution round the axis PS describes a sphærical concavo-convex solid to the several equal particles of which there tend equal centripetal forces; I say that the force with which that solid attracts a corpuscle situate in P, is in a ratio compunded of the ratio of the solid and the ratio of the force with which the given particle in the place Ff would attract the same corpuscle.

For if we consider first the force of the sphærical

superficies FE which is generated by the revolution

of the arc FE, and is cut any where, as

in r, by the line de; the annular part of the superficies

generated by the revolution of the arc rE

will be as the lineola Dd, the radius of the sphere

PE remaining the same; as Archimedes has demonstrated

in his book of the sphere and cylinder.

And the force of this superficies exerted in the

direction of the lines PE or Pr situate all round

in the conical superficies, will be as this annular

superficies it self; that is as the lineola Dd, or

which is the same as the rectangle under the given

radius PE of the sphere and the lineola Dd; but

that force, exerted in the direction of the line PS

tending to the centre S, will be less in the ratio

of PD to PE, and therefore will be as FD x Dd.

Suppose now the line DF to be divided into innumerable

little equal particles, each of which call

Dd; and then the superficies FE will be divided

into so many equal annuli, whose forces will be as

the sum of all the rectangles PD x 'Dd, that is, as

, and therefore as . Let

now the superficies FE be drawn into the altitude

Ff; and the force of the solid EFfe exerted

upon the corpuscle P will be as ; that

is, if the force be given which any given particle

as Ff exerts upon the corpuscle P at the disŧance

PF. But if that forte be not given, the force of

the solid EFfe will be as the solid

and that force not given, conjunctly. Q. E. D.

Proposition LXXX. Theorem XL.

If to the several equal parts of a sphere ABE, (Pl. 22. Fig. 6.) described about the centre S, there tend equal centripetal forces; and from the several points D in the axis of the sphere AB in which a corpuscle, as, is placed, there be erected the perpendiculars DE meeting the sphere in E, and if in those perpendiculars the lengths DN be taken as the quantity and as the force which a particle of the sphere situate in the axis exerts at the distance PE upon the corpuscle P, conjunctly; I say that the whole force with which the corpuscle P is attracted towards the sphere is as the area ANB, comprehended under the axis of the sphere AB, and the curve line ANB, the locus of the point N.

For supposing the construction in the last lemma and theorem to stand. conceive the axis of the sphere AB to be divided into innumerable equal particles Dd, and the whole sphere to be divided into so many sphærical concavo-convex laminæ 'EFfe; and erect the perpendicular dn. By the last theorem the force with which the laminæ EFfe attracts the corpuscle P. is as and the force of one particle exerted at the distance PE or PF, conjunctly. But (by the last lemma) Dd is to Ff as PE to PS, and therefore Ff is equal to and is equal to and therefore the force of the laminæ EFfe and the force of particle exerted at the disŧance PF conjunctly; that is supposition, as DN x Dd, or as the evanescent area DNnd. Therefore the forces of all the laminæ exerted upon the corpuscle P are as all the areas DNnd, that is, the whole force of the sphere will be as the whole area ANB. Q. E. D.

Cor. 1. Hence if the centripetal force tending to the several particles remain always the sæme at all distances, and DN be made as the whole force with which the corpuscle is attracted by the sphere is as the area ANB.

Cor. 2. If the centripetal force of the particles be, reciprocally as the distance of the corpuscle attracted by it, and DN be made as the force with which the corpuscle B is attracted by the whole sphere will be as the area ANB.

Cor. 3. If the centripetal force of the particles be reciprocally as the cube of the distance of the corpuscle attracted by it, and DN be made as the force with which the corpuscle attracted by the whole sphere will be as the area ANB.

Cor. 4. And universally if the centripetal force tending to the several particles of the sphere be supposed to be reciprocally as the quantity V; and DN be made as ; the force with which 5 corpuscle is attracted by the whole sphere will be as the area ANB.

Proposition LXXXI. Problem XLI.

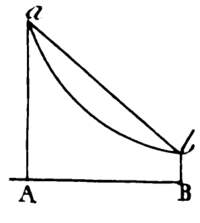

The things remaining as above it is required to measure the area ANB. (Pl. 23. Fig. 1.)

From the point P let there be drawn the right line PH touching the sphere in H; and to the axis PAB letting fall the perpendicular HI, bisect PI in L; and (by prop. 12. book 2. elem.) is equal to . But because the triangles SPH, SHI are alike. or is equal to the rectangle PSI. Therefore is equal to the rectangle contained under PS and PS + SI + 2SD; that is under PS and 2LD. Moreover is equal to , or , that is, . For or (by prop. 6. book 2. elem.) is equal to the rectangle ALB. Therefore if instead of we write ; the quantity , which (by cor. 4. of the foregoing prop.) is as the length of the ordinate DN will now resolve it self into three parts ; where if instead of V we write the inverse ratio of the centripetal force, and instead of PE the mean proportional between PS and 2LD; thos three parts will become ordinates to so many curve lines, whose areas are discovered by the common methods. Q. E. D.

Example 1. If the centripetal force tending to the several particles of the sphere be reciprocally as the distance; instead of V write PE the distance; then . Suppose DN equal to its double ; and 2SL the given part of the ordinate drawn into the length AB will describe the rectangular area 2SL x AB; and the indefinite part LD, drawn perpendicularly into the same length with a continued motion, in such fort as in its motion one way or another it may either by increasing or decreasing remain always equal to the length LD, will desrive that is, the area SL x AB; which taken from the former area 2SL x AB leaves the area SL x AB. But the third part , drawn after the same manner with a continued motion perpendicularly into the same length, will describe the area of an hyperbola, which subducted from the area SL x AB will leave ANB the area sought. Whence arises this

construction of the problem. At the points L, A, B

making Aa equal to Ll, and Bb equal to LA. Making Ll, and LB asymptotes, describe through the points LA, the hyperbolic curve ab. And the chord ba being drawn will inclose the area aba equal to the area sought ANB.

Example 2. If the centripetal force tending to the several particles of the sphere be reciprocally as the cube of the distance, or (which is the same thing) as that cube applied to any given plane; write for V, and 2PS x LD for ; and DN will become as that is (because PS, AS, SI are continually proportional) as . If we draw then these three parts into the length AB, the first will generate the area of an hyperbole; the second , the area ; the third , the area that is . Form the first subduct the sum of the second and third, and there will remain ANB the area sought. Whence arisfes this

construction of the problem. At the points

L, A, S3, B, (Fig. 3.) erect the perpendicualrs Ll, Aa, Ss, Bb, of which suppose Ss equal to SI; and through the point s, to the asymptotes Ll, LB, describe the hyperbola asb meeting the perpendiculars Aa, Bb, in a and b; and the rectangle 2ASI subducted from the hyperbola AasbB, will leave ANB the area sought.

Example 3. If the centripetal force tending to

the several particles of the spheres decrease in a

quadruplicate ratio of the distance from the particles;

write for V, then for PE, and

DN will become as

These three parts drawn into the length AB, produce

so many areas, viz. into ; into ; and into . And these after due reduction come forth , and . And

these by subducting the last from the first become

. Therefore the entire force with which

the corpuscle P is attracted towards the centre of

the sphere is as , that us reciprocally as . Q. E. I.

By the same method one may determine the attraction of a corpuscle situate within the sphere, but more expeditiously by the following theorem.

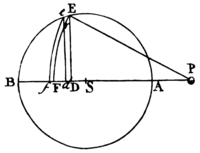

Proposition LXXXII. Theorem XLI.

In a sphere described about the centre S (Pl. 23. Fig. 4.) with the interval SA, if there be taken SI, SA, SP continually proportional; I say that the attraction of a corpuscle that the attraction of a corpuscle within the sphere in any place I, is to its attraction without the sphere in the place P, in a ratio compounded of the subduplicate ratio of IS, PS the distances from the centre, and the subduplicate ratio of the centripetal forces tending to the centre in the places P and I.

As if the centripetal forces of the particles of the sphere be reciprocally as the distances of the corpuscle attracted by them; the force with which the corpuscle situate in I is attracted by the entire sphere, will be to the force with which it is attracted in P, in a ratio compounded of the subduplicate ratio of the distance SI to the distance SP, and the subduplicate ratio of the centripetal force in the place I arising from any particle in the centre, to the centripetal force in the place P arising from the same particle in the centre, that is, in the subduplicate ratio of the distances SI, SP to each other reciprocally. These two subduplicate ratio's compose the ratio of equality, and therefore the attractions in I and P produced by the whole sphere are equal. By the like calculation if the forces of the particles of the sphere are reciprocally in a duplicate ratio of the distance, it will be found that the attraction in I is to the attraction in P as the disŧance SP to the semi-diameter SA of the sphere. If those forces are reciprocally in a triplicate ratio of the distances, the attractions in I and P will be to each other as to ; if in a quadruplicate ratio as to . Therefore since the attraction in P was found in this last case to be reciprocally as , the attraction in I will be reciprocally as , that is, because is given, reciprocally as . And the progression is the same in infinitum. The demonstration of this theorem is as follows.

The things remaining as above constructed and a corpuscle being in any place P, the ordinate DN was found to be as . Therefore if IE be drawn, that ordinate For any other place of the corpuscle as I, will become (mutatis mutandis) as . Suppose the centripetal forces flowing from any point of the sphere as E, to be to each other at the disŧances IE and PE, as to , (where the number in n denotes the index of the powers of PE and IE) and those ordinates will become as and whose ratio to each other is as to . Because SI, SE, SP are in continued proportion, the triangles SPE, SEI are alike; and thence IE is to PE as IS to SE or SA. For the ratio of IE to PE write the ratio of IS to SA; and the ratio of the ordinates becomes that of to . But the ratio of PS to SA is subduplicate of that of the distances PS, SI; and the ratio of to (because IE is to PE as IS to SA) is subduplicate of that of the forces at the distances PS, IS. Therefore the ordinates, and consequently the areas which the ordinates describe, and the attractions proportional to them, are in a ratio compounded of those subduplicate ratio's. Q. E. D.

Proposition LXXXIII. Problem XLII.

To find the force with which a corpuscle placed in the centre of sphere is attracted towards any segment of that sphere whatsover.

Let P (Pl. 23. Fig. 5.) be a body in the centre of that sphere, and RBSD a segment thereof contained under the plane RDS and the sphærical superficies RBS. Let DB be cut in F by a sphærical superficies EFG described from the centre P, and let the segment be divided into the parts BREFGS, FEDG. Let us suppose that segment to be not a purely mathematical, but a physical superficies, having some, but a perfectly inconsiderable thickness. Let that thickness be called O and (by what Archimedes has demonstrated) that superficies will he as PF x DF x O. Let us suppose besides the attractive forces of the particles of the sphere to be reciprocally as that power of the distances, of which n is index; and the force with which the superhcies EFG attracts the body P, will be (by prop. 79.) as, that is, as . Let the perpendicular FN, drawn into O be proportional to this quantity; and the curvilinear area BDI, which the ordinate FN, drawn through the length DB with a continued motion will describe, will be as the whole force with which the whole segment RBSD attracts the body P. Q. E. I.

Proposition LXXXIV. Problem XLIII.

To find the force with which a corpuscle, placed without the centre of a sphere in the axis of any segment, is attracted, by that segment.

Let the body P placed in the axis ADB of the segment

EBK (Pl. 23. Fig. 6.) be attracted by that

segment. About the centre P with the interval PE

let the sphærical superficies EFK be described;

and let it divide the segment into two parts EBKFE

and EFKDE. Find the force of the first of those

parts by prop. 81. and the force of the latter part by

prop. 83. and the sum of the forces will be the force

Pf the whole segment EBKDE. Q. E. I.

Scholium.

The attractions of sphærical bodies being now

explained, it comes next in order to treat of the

laws of attraction in other bodies consisting in like

manner of attractive particles; but to treat of them

particularly is not necessary to my design. It will be

sufficient to subjoin some general propositions relating

to the forces of such bodies, and the motions thence

arising, because the knowledge of these will be of some

little use in philosophical enquiries.