The Zoologist/4th series, vol 4 (1900)/Issue 709/Spinning Molluscs, Kew

(For an explanation, see page 320 (Wikisource-ed.))

The production of a mucus-thread, as a means of progression through the air, has long been known in the Land-Slugs, and has been observed in seven genera, representing Limacidæ, Arionidæ, and Philomycidæ.

The Spinning-Slug (Limax filans) of authors is a myth, the habit being general, extending possibly to all Slugs of the families named. The animals are occasionally seen descending from trees, fences, rafters in greenhouses, &c, and they are easily induced to descend from small exposed objects on which they may be placed. They crawl from the object, and, when the tail parts company with it, the animal is sustained by a thread, which is left by the body at the tail, and is gradually lengthened. Sometimes the animal thus reaches a new support without a fall, but the faculty is imperfect, the animal often falling either without a thread or after making a short one. Large Slugs, when full-grown, are incapable of this kind of locomotion; but small ones, and the young of large kinds, are occasionally capable of making successful descents of surprising length. Threads measuring 3–7 ft. have several times been observed, and others 8–9 ft. long have been reported.

On the foot of the descending animal wave-like appearances are observable; these are the result of muscular action identical with that giving rise to the creature's ordinary locomotion; and we have here a clue to the nature of the progression through the air and of the thread. Whenever a Slug is in motion it discharges mucus, chiefly from the supra-pedal gland below the mouth; in ordinary locomotion it crawls over a film of this mucus which remains behind as a trail, and when in the air it crawls over a similar film, which collapses into a thread as the animal leaves it; this thread represents the trail in every respect, is derived in the same manner, and is in fact a continuation of it. The thread is lengthened by the continued crawling action, combined with a constant discharge of mucus, and perhaps also by the weight of the animal, which appears to elongate the collapsing film. There is thus no special spinning-organ. The thread, however, is of extreme fineness, and is silky when dry; it generally springs up and floats (remaining attached at the point of origin) when the animal alights; but it sometimes becomes attached to the new support, and is left, marking the animal's aerial course. If the animal does not find a new support, or fall, it sometimes turns upon its thread, ascends it, and regains the former support; it creeps up the thread as on a solid body, the slack (with other mucus emitted during the ascent) accumulating at the tail. It is chiefly when the creatures find themselves exposed to sunshine, dry atmosphere, or other dangers that they crawl from their supports. One doubts, however, whether they derive much advantage from the use of the thread; there is no reason to suppose that they would often be injured if they dropped (as they often do by reason of the imperfection of their spinning). Falls of a few feet do not appear to be harmful; and the writer regards the Slug's spinning as little more than an accidental circumstance resulting from the possession, for ordinary locomotion, of a continuous supply of tenacious mucus.

This faculty of making and using a thread, far from being confined to Land-Slugs, is found to extend not only to shell-bearing Pulmonata, but also to the remaining orders of Mollusca-Gastropoda—Opisthobranchiata, Pectinibranchiata, and Aspidobranchiata (with the possible exception of the last); and the writer's principal object in the present paper is to bring together certain scattered information concerning the so-called spinning habits of these latter creatures—terrestrial, fresh-water, and marine univalves, and Sea-Slugs.[1]

PULMONATA.

In Pulmonata, other than Land-Slugs, spinning chiefly occurs among the air-breathing fresh-water Snails, in which it is probably general. Among the Land-Snails of the order it appears to be very rare; the Helicidæ (typical Snails) are entirely unrepresented, as also, with the exception of a single genus, are all the other groups with Helicoid shells. For Pupidæ we have two notes, but these, as it appears to the writer, are in need of confirmation. With regard to the more or less Helicoid, semi-Slug-like Vitrina pellucida, one finds that Mr. Collinge several times tried, without success, to induce the creature to suspend itself;[2] and a few trials by the writer with various land-shells (which were placed on twigs of needle-furze, &c.) were also unsuccessful, the animals gliding off and falling without a thread, or retiring into their shells and remaining on the twigs. In Testacellidæ, I tried Testacella scutulum; in Vitrinidæ, Vitrina pellucida; in Helicidæ, young Helix aspersa and nemoralis (or hortensis); in Pupidæ, Clausilia laminata and C. rolphii; and in Stenogyridæ, Cochlicopa lubrica.

Zonitidæ.

According to Andrew Garrett, the mucus of Trochonanina conula,[3] and of other species of Trochonanina, is unusually tenacious, "and the animals possess the habit of 'thread-spinning' to perfection"; so much so, it is added, that it requires no small amount of patience, while gathering specimens, to detach them from the fingers, and secure them in the box or vial.[4] These little Snails, as far as the writer has ascertained, are the only Helicoid-shelled molluscs known to make threads; the Trochonanina conula was collected by Garrett from foliage of bushes in the Cook's or Harvey Islands, and in the Society Islands.

Pupidæ.

There is a statement in Mr. Tye's "Molluscan Threads" (1878) that Mr. Dixon, of Leeds, "has seen several individuals of Clausilia rugosa var. dubia suspended."[5] A number of Clausilia rugosa kept by the present writer for a considerable time in glass vessels, with twigs, &c, were not seen, however, to use a thread; and, as indicated above, two other species of Clausilia have been experimented with on twigs of needle-furze with similar negative results. Clausilia rugosa, it is true, was sometimes seen hanging during rest by a point of dried mucus, attaching the lip of the shell to the object of support, and allowing the creature to swing freely; but this, apparently, was merely the result of the breaking away or failure of the greater part of the film by which resting Clausiliæ ordinarily fix the mouth of the shell; a method of attachment familiar to us in the common Snails (Helix, &c). In Helix (and probably in Clausilia also) the mucus of this attachment comes, not from the foot, but from the mantle. On inquiring of Mr. Dixon, in 1893, the writer found that the observation on Clausilia had passed from his memory; he stated, however, that he had seen Balea perversa, in the Isle of Man, suspended by a string of mucus about an inch long from the under side of stone ledges; he supposed that the animals, in crawling over the ledges, had overbalanced, and that their mucus, more glutinous than usual owing to the dry weather prevailing at the time, had held them suspended, and had been gradually drawn out by the weight of the mollusc.

Limnæidæ.

The air-breathing fresh-water Snails of this and the next family are notorious spinners, the habit being associated with the visits to the surface of the water which most of these creatures are compelled to make from time to time for the purposes of respiration. Most of them have light shells, and when the animal is extended, and the lung-sac filled with air, they differ from truly aquatic and truly terrestrial molluscs in being slightly lighter than the medium in which they live; when detached they generally rise to the surface, and from this position they appear to be unable to drop, except when they withdraw into their shells and expel air from the lung-sac. It thus happens that they usually spin upward instead of downward threads—a circumstance in which they differ, as far as the writer has ascertained, from all other molluscs. The process is probably identical with that seen in Limax, but the thread, instead of preventing the animal's fall, prevents its sudden rise to the surface. The animal, gradually raising the anterior part of its foot from the bottom on which it is travelling, crawls upwards through the water upon its slime, which, left behind in the form of a thread, retains the animal as it slowly ascends to the surface, to which, or to the slime-film now deposited there, the thread is fixed; subsequently, crawling down the thread thus fixed, the creature uses it as a means of descent to its former position. Mr. Warington long ago published notes on this subject, but we are chiefly indebted for our information to Mr. Tye.[6] The latter naturalist kept most of the Limnæids of this country in captivity for the purpose of observing their spinning. Some spun both when young and adult, others when young only; and, while some used their threads frequently, others did so rarely or not at all. The observer concludes, however, that all are more or less expert in this respect, and that "in the pellucid stillness of their own domain, when the eye of man is not present to pry into their daily avocations, this beautiful and delicate method of travelling is often used by them." It is maintained by this author, and by Mr. Taylor,[7] that the creatures can spin downward as well as upward threads; and from the observations of these naturalists it certainly appears that when the air in the lung-sac is sufficiently exhausted, the animal is heavy enough, while yet extended from its shell, to descend through the water, making a thread as it goes, and to remain suspended in the water upon a thread thus made. This, however, it is believed, but rarely happens. Several of the observations quoted below, it is true, imply descent and suspension; but, as the thread is generally invisible, it is possible that the animals, in some cases, may have been descending, or resting, upon threads already spun and fixed during ascent. The animal's ability to ascend or descend is attributed by Mr. Tye wholly to the condition of the lung-sac; the creatures are lighter than water, he says, when the sac is inflated, and heavier than water when the air of the sac is exhausted or expelled. It must be remarked, however, that it is when the air is exhausted that the creatures ordinarily require to ascend, and when the sac is fully inflated that they have to descend. It seems to the present writer that the changes in the creature's specific gravity are largely contributed to by the contraction or extension of the animal itself into or from its shell; and it is probable that the creature, when sufficiently heavy to sink, is usually too much contracted and withdrawn to form a thread. It is interesting to note that Mr. Tye recognizes the fact that here, as in Limax, the thread represents the mucus-trail of ordinary progression, such a trail, though usually invisible in the case of a Limnæid, being always present in the track of the moving animal. On plants in vessels in which molluscs have been kept for a few days, Mr. Tye adds, a network of mucus stretches from leaf to leaf, and is readily apparent when fresh water is put in, the bubbles given off by the plants then adhering to the mucus-lines.[8]

Limnæa.—"In watching the movements of Limnæa in the aquarium," says Mr. Warington, "I was for some time under the impression that they had a power of swimming or sustaining themselves in the water, as they would rise from the bottom of the pond, a portion of the rock-work, or a leaf of the plants, and float for a considerable period, nearly out of their shells," without any apparent attachment. On carefully watching this phenomenon, he found that the creatures "were attached by a thread or web, which was so transparent as to be altogether invisible, and which they could elongate in a similar way to the Spider; they also possessed the power of returning upon this thread by gathering it up as it were, and thus drawing themselves back to the point which they had quitted." The observer mentions a case in which a Limnæa stagnalis, having reached the extremity of a leaf of Vallisneria, launched itself off from it; and, after moving about with a sort of swimming or rolling motion in a horizontal direction for some time, lowered itself gradually. During the descent, the flexible leaf was bent with an undulating motion, corresponding with every movement of the Snail, and making it clear that the animal had an attachment to the extremity of the leaf. Proof of the existence of a thread was obtained also by means of an experiment which the observer often repeated with Limnæa stagnalis, L. auricularia, and Amphipeplea glutinosa.[9] When the Snails were some inches from the supposed point of attachment, a rod was introduced, and slowly drawn on one side in a horizontal direction; and, by this means, the Snails were made to undulate to and fro, obeying exactly the movement of the rod. This had to be done gently, for when too much force was used the thread broke, and the animal rose rapidly to the surface. According to Mr. Tye's observations, Limnæa glabra spins its upward thread well and easily; L. stagnalis, when young, does the same, but the habit decreases as the animal grows older; the same is the case with L. palustris, which, however, was not seen to use a thread as often as L. stagnalis. L. auricularia, L. truncatula, and L. peregra, though kept under observation by Mr. Tye, were not seen by him to spin. Mr. R.M. Lloyd, however, had observed the habit in the last-named species. The present writer has noted L. peregra and L. palustris, presumably retained by threads, slowly rise through the water in aquaria; the L. peregra, which was extended as if crawling on a solid body, did not always keep its foot in the same plane, from which fact the writer concludes that it was not creeping up a thread already fixed. The water through which it rose was about eight inches deep; and, on arriving at its destination, the animal applied its foot to the surface-film of the water, under which it crept in the usual inverted position. In L. auricularia, the use of a thread was observed, as we have just seen, by Mr. Warington. Mr. Taylor, also, has seen this species spin, and has recently published a figure of an individual using a thread. This figure (Fig. 1) shows the animal, moderately extended from its shell, suspended from the surface of the water upon a downward-spun thread. The drawing was at first supposed by the writer to be inaccurate; but Mr. Taylor, replying to an enquiry, states that it represents an observation made in his aquarium in 1889; and assures me that he has several times witnessed the formation, by Limnæids, of short downward threads.

Amphipeplea.—The use of a thread by Amphipeplea glutinosa[10] has been observed, as already noted, by Mr. Warington. One individual was seen to gradually rise, from a piece of rock in the aquarium, to a distance of three to four inches; it then stayed its progress, and soon afterwards rose suddenly and rapidly to the surface, the retaining thread having evidently given way. Professor Tate has remarked that the water in which this animal is kept, if shallow and insufficient, "is soon rendered glutinous with their mucus-threads";[11] and Mr. F.W. Fierke, who kept specimens in a jar, mentions threads of mucus "connecting weed to weed, and sometimes even decorating the shells of other molluscs with which L. glutinosa had evidently come in contact"; he mentions, also, having observed the animal gently rise through the water.[12]

Planorbis.—In the flattened Limnæids of this genus (coil-shells), we are again indebted, for the first observation, to Mr. Warington, who appears to have seen the habit in several species. Mr. Tye saw it—less frequently than in Limnæa—in Planorbis spirorbis, P. carinatus, P. complanatus, and P. contortus, but not in six other species kept under observation. In P. complanatus the habit has been noted, also, by Mr. Musson.[13]

Segmentina.—Segmentina lineata[14] was kept by Mr. Tye, but was not seen to spin. We have a statement by Professor Cockerell, however, that one of his brothers, who had been keeping specimens in a bell-jar, had seen one "spinning a downward thread" from the surface of the water to the bottom of the bell-jar.[15]

Ancylus: aberrant Limnæids (fresh-water Limpets).—Mr. Clark, long ago. saw that Ancylus fluviatilis living on pebbles in brooks with a rapid current, must find it difficult to visit the surface to breathe, unless, as he suggests, it has the power "of veering out a filamentary cable," by which it can return to its original site.[16] It is probable, however, that the species of Ancylus are not bound, like the majority of Limnæids, to visit the surface; and, in all probability, they do not spin upward threads. For Ancylus lacustris we have a note by Mr. Taylor:—

"My valued correspondent, Mr. T.D.A. Cockerell, has communicated to me the interesting circumstance that this species has the power possessed by many other Lymnæidæ of spinning a mucus-thread. He says: 'I have just been watching a young specimen of Ancylus lacustris spinning a downward thread.' According to the rough but characteristic sketch of the circumstance made by Mr. Cockerell, the thread was about half an inch long, attached to the extremity of a leaf of the Anacharis, the body of the animal being bent during the operation, the head and tail nearly close together."[17]

The sketch referred to was not published by Mr. Taylor; but the writer is permitted to give a copy of it (Fig. 2). The animal appears to be the only mollusc with a Limpet-like shell known to produce a thread.

Physidæ.

The air-breathing freshwater Snails of this family resemble Lymnæidæ in habits; but they possess greater activity, and make a more general use of threads. Montagu (1803) states that Physa fontinalis[18] "will sometimes let itself down gradually by a thread affixed to the surface of the water, in the manner of the Limax filans from the branch of a tree."[19] Here, however, as in some other cases, the animals observed were possibly descending threads already fixed; for Physids, like Limnæids, are ordinarily slightly lighter than water; and they spin their threads generally, if not invariably, during ascent. The habit was noticed also in Physa fontinalis by Mr. Warington, who states that on one occasion introducing a rod between the creature and its point of attachment, he moved it out of its straight course a considerable distance; and, by then slowly drawing the rod upwards, he succeeded in raising the Snail out of the water, a space of about seven inches, suspended by its thread, which, though difficult to see in the water, now became distinctly visible. Mr. Tye chiefly observed Physa hypnorum; he states, however, that P. fontinalis uses its thread in a similar way, though less frequently. According to this observer, the young, as soon as they issue from the egg, are capable of spinning a thread and rising to the surface of the water: —

"If my readers wish to see for themselves this habit of travelling, as used by the mollusca, let them take a few adult Physa hypnorum ... place them in a glass vessel with some small pebbles at the bottom and a little weed ... and keep them until they deposit spawn. As soon as the young are free from the spawn mass they will commence spinning, and practise it so often that the process may be seen at any time."

All the threads observed were spun upwards during ascent to the surface; the longest were the work of P. hypnorum, and were spun in a vessel in which the water was fourteen inches deep; they extended from the bottom to the surface. When a P. hypnorum, spinning its upward thread, was much disturbed, it was seen to abandon the idea of reaching the surface, and to turn and descend the unfinished thread, altering its position, Mr. Tye says, with much dexterity and ease by bringing its extremities together, and changing the point of attachment of the thread from the tail to the head. This is certainly a curious performance; but, allowing for the reversed condition of specific gravity, it will be noted that it exactly corresponds with the turning and ascent of a thread by Limax; the buoyancy of Physa, of course, keeps the thread taut, just as does the weight of Limax. When the animal completes its thread, it attaches it at the surface of the water, a minute concavity at the upper end acting, according to Mr. Tye's description, like a small boat, of air, and sustaining the thread; but it is more correct to say, perhaps, that the thread is continued at the surface in the form of a floating slime-trail, and that, thus anchored, it slightly cups the water's surface-film. When the Physa returns from the surface by descending its thread, Mr. Tye further observes: the thread—not invariably gathered up and carried back—sometimes remains attached to the surface; and in that case, it may be used, both for ascent and descent, as a more or less permanent ladder; it is strengthened by an additional trail of mucus each time a mollusc passes over it, and thus it becomes somewhat strong and lasts for a considerable time. Mr. Tye had young P. hypnorum crawling up and down fixed threads of this kind for eighteen to twenty days together; and on one occasion he noted three individuals, and a Limnæa glabra, upon a Physa's thread at the same time: —

"Often, when two Physæ meet upon the same thread, they fight as only molluscs of this genus can, and the manoeuvres they go through upon their fairy ladders outdo the cleverest human gymnast that ever performed. I once saw one ascending, and when it was half-way up the thread it was overtaken by another; then came the 'tug of war'; each tried to shake the other off by repeated blows and jerks of its shell, at the same time creeping over each other's shell and body in the most excited manner. Neither being able to gain the mastery, one began to descend, followed by the other, which overtook it, reaching the bottom first. Yet they are not always bent upon war, but pass and repass each other in an amicable spirit. One of the most beautiful sights in the molluscan economy is to see these little 'golden pippins' gliding through the water by no visible means; and when they fight, to see them twist and twirl, performing such quick and curious evolutions, while seemingly floating in mid-water, is astonishing, even to the patient student of Nature's wonders."

This use of threads as more or less permanent ladders is unique, as far as the writer knows, among all the mollusca. Mr. W. Jeffery, who kept Physa hypnorum in an aquarium, has referred to the creature's habit of spinning a thread while rising perpendicularly to the surface; he notes that after taking in a supply of air it may turn leisurely about and crawl down the same thread; and mentions that once, while the animal was thus returning, the thread parted from its mooring, "when poor hypnorum was quickly carried to the surface again by the air it had taken in."[20] Mr. Musson, further, mentions having observed spinning both by P. hypnorum and P. fontinalis[21]; and Mr. Standen, who refers to P. fontinalis, has obligingly informed the writer of observations made by him. The last-named naturalist remarks particularly upon the junction of the thread with the surface of the water, stating that the point of attachment is plainly visible, especially when the sun's rays fall upon the water of the tank in which the animals are kept; he compares the cupping of the surface-film (which can be conveniently examined with a lens) to a small inverted parachute, and states that it is shown to perfection when affected by the jerking motions of an ascending Snail. The accompanying diagram, based upon the observations here stated for Physa, will serve, in a general way, to illustrate the use of threads by aquatic Pulmonates. (Fig. 3.)

OPISTHOBRANCHIATA.

Suborders Tectibranchiata and Nudibranchiata (Sea-Slugs). Of Tectibranchs. only one family—Philinidæ—is here represented; and that only by the following note by Mr. Spence Bate:—

"The fact, observed by Mr. Warington, of the power of the Limnæus to move from one place to another by means of a mucous suspending cord, I have observed also to be the case with Bulla aperta [Philine aperta] in the vivarium of my friend Mr. Smyth; but the power of secreting the mucus, which is exuded from the external surface of the animal, is limited in its continuance; to prove the fact, we raised it three times to a glass shelf in the vivarium; the last time, not being able to secrete the ladder, it fell head over heels, and therefore lost the power of choosing its place below, as it could do when it came down by the cord."[22]

In the Nudibranchs (typical Sea-Slugs) the production of a thread has been noted in at least four families, and is perhaps general. As the creatures are not ordinarily lighter than water, they do not spin upward threads; like Limax, like the Philine just noted, and, like most other gastropods, they produce their mucus-lines during descent. While crawling at the surface of water, Alder and Hancock state:—"The Nudibranchs occasionally drop suddenly down, suspending themselves from the surface by a thread of mucus, which is fixed to the tail or posterior extremity of the foot. In this way they will let themselves gradually down to the bottom, or remain some time pendent in the water without apparent support; for the thread of mucus is so transparent that it can scarcely be seen. When carefully looked for, however, it can always be perceived, originating in the track of mucus left on the surface by the animal, the mucus forming a small inverted cone at the point from which the thread issues, and here slightly dimpling the surface of the water."[23] It appears, from an observation by Gray on Elysia, that the suspensory thread can be subsequently ascended by the animal.

Polyceridæ.

Thompson states that three Sea-Slugs believed to pertain to Polycera quadrilineata,[24] kept in a phial of sea-water, were generally seen suspended by their threads from the surface, the body at the same time moving freely about with much grace.[25] Polycera lessonii, Alder and Hancock mention, may be seen, in captivity, for hours together, "suspended by a film of raucous matter from the surface of the water."

Dorididæ.

Chromodoris amabilis[26] (Ceylon), according to Kelaart, sometimes creeps at the surface, and "when touched with a feather it adheres by its foot, and can be kept dangling in this position by the aid of the mucous thread secreted by the surface of the foot."[27]

Eolididæ.

Mr. Sinel mentions having frequently observed Eolis hanging by a thread from the water-surface, the suspended animal having the body doubled up, Hedgehog-like, with the back downwards.[28] The writer learns from Mr. Hornell that the animal thus referred to by his colleague is Facelina coronata.[29] The thread, Mr. Hornell states,[30] is sometimes 4-5 in. in length.

Elysiidæ.

Elysia viridis,[31] from Swanage Bay, kept by Gray in a vase, usually rested, attached by the tail to the glass, with the body freely extended into the water, and the mantle-edges expanded; when the vase was moved or otherwise shaken, the animal contracted the mantle over its back, and descended "head foremost, as it were dropping down to the bottom, leaving a mucous filament attached to the glass"; subsequently, Gray adds, it ascended by the filament, rising thus towards the surface, and becoming attached to the glass as before.[32]

Limapontiidæ.

A supposed planarian-worm, Planaria variegata—probably a Limapontia[33]—was observed by Dalyell to be liable, in crawling up the side of a vessel, to drop to the bottom, its descent being apparently retarded, the observer says, by an invisible thread.[34]

ASPIDOBRANCHIATA.

In the whole of the Aspidobranchiata we have but a single observation, and this, it is said, requires confirmation. It is not surprising that no case of spinning occurs among the Limpet and Limpet-like families; but the absence of records for the land operculates of the order—Helicina, &c.—is less easy to understand, especially in view of the fact that several of the land operculates regarded as Pectinibranchiata are known to suspend themselves. The Aspidobranch said to be a spinner is our little fresh-water nerite (Neritina fluviatilis), whose name appears in this capacity in most of the books; its only claim to notoriety in this respect, however, rests upon the fact that it was listed by Mr. Warington (with several air-breathing Water-Snails) as having been observed by him to spin.[35] No particulars are given, and it is supposed by Mr. Tye that the observer may have been mistaken.[36]

PECTINIBRANCHIATA.

In Pectinibranchiata the spinners occur chiefly among the mainly phytophagous kinds, which live on seaweed growing near the shore or floating on the surface of the ocean, on aquatic plants in brackish and fresh water, and on branches and aerial roots of trees, bushes, &c, by the water's edge and on land; we have also a few notes for kinds living on rocks, coral, &c.; as well as for others whose habitats afford less facilities for the exercise of the faculty. Among the notoriously carnivorous Sea-Snails, Whelks, Murices, Purples, &c, we have no observations; nor have we any for the Volutes, Olives, Harps, Cones, &c.; among the Mitres, we have one known spinner; and among the Cowries, one. Some of these animals are of large size, but nearly all those with which we are concerned are small, or of moderate growth. These creatures, like other spinning molluscs (except air-breathing Water-Snails), are generally heavier than the medium in which they live, and thus they spin during descent; the threads in many cases are doubtless used for purposes of locomotion; in other cases, however, their chief function seems to be the retention of animals liable to be shaken from their supports during high waves and winds; in still other cases the threads appear to serve chiefly as means of attachment and suspension during repose, the creatures being upheld at this time sometimes by one and sometimes by several or many threads. Most spinning Pectinibranchs, no doubt, are able to ascend to their former positions by crawling up the suspensory thread; this has been observed in Litiopa, in Valvata, and perhaps in Rissoa.

In the molluscs above considered—air-breathing Water-Snails and Sea-Slugs—the threads are doubtless of the nature of those of Limax, being derived from anterior glands, and representing the mucus-trail of ordinary locomotion. The same is probably the case with some of the spinners of the present order; but the writer is doubtful on this point, for the foot in Pectinibranchs, often of peculiar construction, serves for locomotion, differing somewhat from that with which we are familiar in other gastropods. In some cases figures of the foot show conspicuously the long transverse slit-like opening of an anterior pedal gland, whence the mucus of the thread might presumably be derived. In many Pectinibranchs, however, in addition to the anterior gland, a ventral pedal pore exists in the median line of the anterior half of the foot-sole; it forms the opening of a cavity said to be comparable to the byssal-cavity of bivalves, and from it, externally, a well-marked groove often runs to the tip of the tail. It can hardly be doubted that the threads, in many Pectinibranchs, are derived from this ventral pore; in Cerithiopsis tubercularis, for instance, Jeffreys appears to have clearly seen the thread issue from "the opening in the centre of the foot-sole"; a narrow but deep groove extends from this opening to the tail, and Jeffreys tells us that it is by the tip of the tail that this animal attaches its thread to an object of support.

Cyclophoridæ.

In Borneo, the writer was informed by Mr. Everett, certain land-operculates of this family, species of Alycæus, have the habit of suspending themselves, by a single thread, beneath overhanging ledges of the limestone rocks on which they abound. Mr. Everett often saw numbers hanging in this way, during rest, by threads which, to the best of his recollection, were sometimes an inch long; the habit, he adds, may "save them from the attacks of such foes as, for instance, Land-planarians, which are most frequently to be found in the same situations as these Mollusca, and which I have observed to prey on small Helices, which, however, have not the protecting operculum of the Alycæi." That molluscs thus escape certain enemies seems highly probable, and it is perhaps a mistake to suppose that operculates are already sufficiently protected; for Lucas, in Algeria, observed that numbers of Cyclostoma voltzianum, in spite of the operculum, are destroyed by the larvæ of a Drilus.[37]

According to Swainson, "Megalomastoma suspensum, Guilding," is often found suspended by glutinous threads; and the remark is illustrated by a woodcut showing a shell of considerable size hanging from a twig by threads of moderate length, thirteen to fourteen in number, arranged upon the twig in four groups, but all proceeding from one point from between the operculum and the outer lip of the shell. (Fig. 4.)[38] From the fact that Guilding lived at St. Vincent, the creature is probably West Indian; but unfortunately no description of it has been published, and its identity cannot be ascertained. The information and figure were probably derived from Guilding's unpublished papers, of which Swainson is known to have made use. The figure, perhaps worked up from a rough sketch not intended for publication, is probably inaccurate, and much enlarged; it does not appear to represent Megalomastoma antillarum, Sowerby, or M. guildingianum, Pfeiffer, to which names "Megalomastoma suspensum" has been referred; and Mr. E.A. Smith (British Museum), who has obligingly considered the figure for the writer, thinks that it represents, possibly, Cistula lineolata, a small West Indian shell, of which the Museum acquired unnamed specimens at the sale of Guilding's collection. If this be the case, of course, our spinner belongs not to the present, but to the following family.

Cyclostomatidæ.

In some notes forwarded to 'Loudon's Magazine' in 1831, Guilding mentions a "Cyclostoma" common in the Virgin Islands, which, having given out a mucous thread, closes the operculum, and swings by the thread when hardened by the air, safe from ants and other enemies.[39] This note was received in the year preceding that of Guilding's death, and, as he does not mention any other thread-making operculate, the writer presumes that this "Cyclostoma" is identical with the "Megalomastoma suspensum." In this case, in the circumstances just mentioned, the creature is possibly a Cistula; and we find it stated by Mr. R.J.L. Guppy that Cistula aripensis[40] (Trinidad) frequently suspends itself by two or three glutinous threads from branches, or from the under surface of leaves.[41] Mr. Guppy, replying to an enquiry, has had the kindness to inform the writer that this little shell, ½–¾ in. long, is the only mollusc known to him in Trinidad to hang suspended, and that the threads are sometimes of considerable length. Chondropoma dentatum[42] (Key West), a shell about half an inch long, is stated by Binney to spin a short thread, and hang suspended by it during rest; and at the end of one of his chapters the author gives a small woodcut, which, though not described, evidently represents this shell, slightly enlarged, hanging by a short thread from a leaf-stalk; the thread, according to the drawing, proceeds from between the operculum and the outer lip of the shell, considerably nearer to the umbilicus than to the suture. (Fig. 5.)[43]

Another species, Chondropoma plicatalum, a little larger than the last, was obtained by Dr. J.S. Gibbons, at Puerto Cabello, hanging suspended during repose by a thread ⅓–½ in. long, very thin, but strong, flexible, and silk-like; the thread issued from between the operculum and the outer lip, two-thirds of the latter's length from the suture, a position similar to that shown in Binney's drawing.[44] Similar suspension was observed by Dr. Gibbons also in the allied Tudora megacheila. Near St. Ann's, Curaçao, on a waste piece of ground which appears to have been a kind of conchologist's paradise, he found this creature in great abundance, "suspended by its silk-like thread from Acacia boughs, or strewed thickly along the ground underneath"; the thread resembled that of Chondropoma plicatulum, but was shorter.[45]

Among Old-World Cyclostomas, we have a note relating to Cyclostoma articulatum, a shell of considerable size, belonging to Rodriguez (Mascarene Islands):—"When it retired and closed its shell," says Woodward of a specimen kept under a bell-glass, "it still adhered, and sometimes became suspended, by a tenacious thread of mucus."[46] It would have been interesting to have had more particulars of this attachment, for, according to Dr. Gibbons, the South African Cyclostomas fix their shells by a brittle pellicle of dried mucus, proceeding from the edge of the columellar lip, a mode of attachment, as he states, wholly different from that of Chondropoma and Tudora, whose flexible silk-like thread, as just mentioned, passes between the outer lip and the operculum.[47]

Littorinidæ.

Gray has listed Littorina with Pectinibranchs capable of making threads,[48] but the writer does not know on what authority. For repose, out of the water, most of these Periwinkles closely fix their shell by a pellicle of dry mucus, compared by Gibbons to that of the Old-World Cyclostomas, and by Jeffreys and others to the attaching film of Helix.[49] Of Lacuna, however, which belongs to this family, Jeffreys states that the creatures "occasionally secrete slimy threads (like the Limax arborum), by which they suspend themselves from the frond or stalk of a seaweed."[50]

Rissoidæ.

The use of threads is presumably general among Rissoidæ—small, often minute molluscs, which swarm on seaweeds and grasswrack in pools and shallows, as well as on and under stones in some of the deeper waters of the coast. It was in 1833 that Gray made an often quoted observation to the Zoological Society of London, that "the animal of Rissoa parva has the power of emitting a glutinous thread, by which it attaches itself to floating seaweeds, and is enabled, when displaced, to recover its previous position";[51] and we find it is stated by Jeffreys, for Rissoa generally, that the foot is grooved down the middle for about half its length towards the tail, whence it emits a glutinous thread, by which the animal suspends itself to foreign bodies or to the surface of the water.[52] "Lying on a rock by the brink of a seaweed-covered pool left by the receding tide," says Jeffreys, writing of Rissoa parva, "it is no less pleasant than curious to watch the active little creature go through its different exercises—creeping, floating, and spinning."[53] By "floating" the author means, evidently, creeping at the surface of the water, a habit which here, as in other molluscs, seems intimately associated with that of "spinning." The same naturalist mentions the latter habit in several other species: Rissoa membranacea, he says, "occasionally floats, or suspends itself by a viscous thread"; R. vitrea "suspends itself by a single byssal thread, keeping the mouth of the shell closed by the operculum"; R. abyssicola "floats like its congeners, and suspends itself in the water by a single byssal thread"; R. pulcherrima, exceedingly agile both in creeping and floating, "spins a delicate thread of attachment"; and the very tiny R.fulgida was frequently observed by the author "spinning a fine transparent slimy thread, and thus hanging suspended to a bit of seaweed or to the surface of the water." R. cancellata, Jeffreys further says, "is active and bold, floats like its congeners, and spins a byssal thread instantly on being detached from a crawling position"; R. carinata,[54] moreover, like R. cancellata, "adheres with some tenacity to the stones on which it is found, and, when detached, it also spins a fine byssal thread, by means of which it suspends itself in the water."[55] This last species,[56] according to Mr. Brockton Tomlin's experience in the Channel Islands, is usually found under rather deeply-buried stones, to which it moors itself, he says, by a strong "byssus";[57] each individual, this observer obligingly tells the writer, had more than one short thread, generally, as far as he remembers, four or five. Barleeia rubra, according to Jeffreys, creeps at the surface, foot uppermost, like the Rissoæ, and occasionally secretes a slight mucous filament, by which it suspends itself from the surface of the water or from seaweeds.[58]

Hydrobiidæ.

Lindström (1868) has referred to the spinning of a mucus-thread (by which the animal, with half-closed operculum, keeps itself suspended from the water-plants) as a character, among others, tending to associate the fresh-water Bythiniæ with the estuarine Hydrobiids.[59] Bythinia, now always regarded as a Hydrobiid, is certainly a spinner, Mr. Tye having seen Bythinia tentaculata suspend itself, usually after "floating," the thread being attached to the surface of the water;[60] but the writer is not acquainted with observations on other members of the family. In 1894 I kept several specimens of Hydrobia ulvæ and one of H. ventrosa under observation for ten days, in a vessel of water with weed, &c.; they often "floated" (crept at the surface of the water), but were not seen to suspend themselves.

Skeneidæ.

Skenea planorbis, according to Jeffreys, "occasionally suspends itself in the water by spinning a viscous thread with its foot."[61]

Jeffreysiidæ.

Jeffreysia diaphana, also, according to the same author, "spins a slimy suspensile thread."[62]

Litiopidæ.

Litiopa melanostoma, a small, more or less Rissoa-like creature (less than a quarter of an inch in length of shell), an inhabitant of the gulf-weed of the mid-Atlantic (Sargasso Sea), is perhaps the most notorious of all the spinning molluscs. Its history is briefly as follows: —

(1). Bélanger discovered the creature in 1826, and made a number of observations on its habits; and, on his return to France, read his notes to Rang, at the same time handing him spirit specimens, and suggesting for the animals (regarded as belonging to two species), the names of Bombyxinus melanostoma and B. uva.

(2). Rang, from information thus obtained, drew up a memoir, and published it in 1829. He disregarded Bélanger's MS. names, however, and described the shells as Litiopa melanostoma and L. maculata.[63]

(3). Bélanger (1833?), dissatisfied with Rang's account, gave full details of his observations, the name Bombyxinus being here published for the first time.[64]

(4). Kiener (1833) restated Bélanger's observations, and united the two supposed species as Litiopa bombix.[65]

(5). Eydoux and Souleyet, during the voyage of the 'Bonite,' re-collected specimens from the gulf-weed, and are believed to be the only naturalists, other than Bélanger, who have published observations on the living animal. This they did in 1839.[66]

(6). Naturalists agree that the two forms should be united; but Kiener's name is inadmissible (as also are those of Bélanger, over which the names of Rang have priority of publication). The creature—with Litiopa maculata among the synonymy—is now known as Litiopa melanostoma.

(7). Nearly all the books contain accounts of the animal's spinning habits. These, however, are derived from Rang and Kiener (without reference to the original notes of Bélanger and Eydoux and Souleyet); the information is thus unsatisfactory; and the tale, being an often-told one, has grown considerably.

Bélanger's notes have the form of extracts from a log, and are evidently the result of careful observation. It was on June 26th that the creature first came up with the gulf-weed, and, on shaking the weed to make the animals fall, Bélanger observed that some remained suspended, at a considerable distance, by an imperceptible thread like that of a small Spider. The thread proceeded from the foot of the mollusc. When the foot was touched with the finger, a thread was drawn out as the finger was slowly moved away, and when the finger was lifted in the air the animal remained suspended to it for a long time, and for a great distance—more than three feet; even when moved about considerably, and otherwise somewhat severely tested, the creature did not fall; and more than a score were experimented upon, always with the same result. The animal—in some at least of these cases—hung, not in its native element, but in the air. On June 28th and 29th more weed inhabited by this animal was fished up, and Bélanger again observed the creature's spinning habits.[67] Speculating upon the use of the thread, he remarks that the creature, born, living, and reproducing on floating weed, incessantly tossed with more or less violence by the very deep ocean, would be lost, when detached by a wave, had it not this faculty of spinning a silk which, like a cable, holds it to its habitat. On July 8th further weed was fished up, but the molluscs were now less numerous; and, having been out of the water some time when experimented upon, but few remained suspended after the weed had been shaken. Providing himself with a bucket of sea-water, however, Bélanger was able to make several observations; some of the animals adhered to his finger, and hung therefrom, both in the air and in the water. An individual which had lowered itself from the weed, on being placed in the water, remained suspended, and, though moved from one side of the bucket to the other, made to sink to the bottom and lifted up again, it still retained its hold. At length the observer allowed the weed to float on the surface, and after some time, to his great satisfaction, he saw the animal ascend by its thread, and replace itself upon the frond from which it had been suspended. Others which were at the bottom of the bucket, on being moved with a branch of weed, attached their silk to it; and when the branch was left floating at the surface some ascended to it by the thread, while others fell again to the bottom. Another observation, which the author regarded as of much interest, was as follows:—He saw issue from two or three of those which were at the bottom of the bucket a little bubble of air, which rose slowly; and, in trying to move it with a frond of the weed, he saw the animal—holding to the bubble by means of its silk—rise through the water. Speculating upon this last observation, Bélanger supposes that the creature would not be entirely lost even if the shaking, which had detached it from the weed, were also strong enough to break its thread; though not anchored it would still have a lifebuoy, and this buoy, floating on the surface of the water, and coming in contact with another plant, would enable the animal to ascend to a new home. Further, the author even thought it possible that the creatures might thus voluntarily change their positions; a family, he supposes, might find their plant insufficient to feed their increasing numbers; whereupon some of them, seeking new feeding-grounds, might abandon themselves to the water, and wait, suspended to their bubbles, till a new plant chanced to be carried to them by the waves. Finally, on Aug. 27th, the creature still occurred on the weed, but in small quantity, and mostly very young. Of those which remained suspended after the weed had been shaken, one of the larger ones was observed, while thus hanging in the air, to reascend by its thread. Placing the animals at the bottom of a bucket of water, the observer left them for the night; but in the morning all were dead, none having ascended to the surface or to the floating weed. Eydoux and Souleyet obtained numerous specimens, and, on shaking the weed on which the animals were brought up, they had no difficulty in confirming Bélanger's statements about the suspensory thread. They appear to have been at considerable pains, however, in attempting, unsuccessfully, to confirm the observations about the mucus-invested air-bubble; specimens were placed at the bottom of deep vessels of water, and allowed to remain there for a considerable time, but none ascended by means of a bubble. Some crept up the sides of the vessels to the water-surface, under which they crept like other gastropods. The appendages which characterize the upper part of the foot of Litiopa may be useful, these authors think, in helping to keep the animal at the surface. Notwithstanding Rang's remark that the thread is doubtless formed of a special secretion, Eydoux and Souleyet think it probable that it consists merely of locomotory mucus, which, in these molluscs, may possibly possess special characters. Rang, it may be added, while examining spirit specimens, found, under the foot, a little glairy mass, which attached itself to the point of the scalpel, and was easily drawn out into a thread a foot and a half long; each specimen presented the same peculiarity, and Rang concluded that this was the substance from which the thread is made; it seems more probable, however, that the little masses were the remains of threads already spun, and perhaps reascended by the animal.

The above, the present writer believes, is all that is known of the spinning habits of Litiopa. These habits are certainly of a surprising character: the length of the apparently rapidly made thread, the animal's security upon it, and the facts that it can produce and afterwards ascend by it, not only in its native element, but also in the air, are points of special interest. As to the statements in the books, one may quote, for example, from Johnston's 'Introduction to Conchology':—

"The habits of the Litiopa are not less worthy of your notice. This is a small Snail, born amid the gulf-weed, where it is destined to pass the whole of its life. The foot, though rather narrow and short, is of the usual character, and, having no extra hold, the Snail is apt to be swept off its weed; but the accident is provided against, for the creature, like a Spider, spins a thread of the viscous fluid that exudes from the foot to check its downward fall, and enable it to regain the pristine site. But suppose the shock has severed their connexion, or that the Litiopa finds it necessary to remove, from a deficiency of food, to a richer pasture, the thread is still made available to recovery or removal. In its fall, accidental or purposed, an air-bubble is emitted, probably from the branchial cavity, which rises slowly through the water, and as the Snail has enveloped it with its slime, this is drawn out into threads as the bubble ascends; and now, having a buoy and ladder whereon to climb to the surface, it waits suspended until that bubble comes into contact with the weeds that everywhere float around!"[68]

The speculations of Bélanger, it will be observed, here appear as statements of established facts, Johnston having been misled by Kiener, whose restatement of Bélanger's observations wants some of the precision of the original notes. Statements in other books (some adapted from Johnston) also exceed what is really known; and some are further objectionable from the fact that they do not make it clear that suspension is likely to be an occasional circumstance, not the usual condition under which the animal lives.

Alaba picta, a Litiopid found by A. Adams among Zostera in shallow water in the seas of Japan, is stated by him to spin a pellucid thread, with great rapidity, from a viscous secretion "emitted from a gland near the end of the tail"; it also creeps at the surface of the water, and, when fatigued, suspends itself, apex downwards, by means of the thread which is attached to the surface.[69]

Valvatidæ.

Valvata piscinalis (familiar in our ponds and canals) was observed to use a thread by Laurent. He noticed that the animals, in crawling at the surface of water, deposited there a trail of mucus, and that, when made to fall, some of them remained suspended to the floating trail by a thread; similarly, others were sustained in the water when forced to leave the branches of the plants on which they lived. In the former case some were seen to remount to the surface of the water by ascending their thread, which was gathered up by the foot.[70] Mr. A.E. Boycott has written of the same animal, immature specimens of which, in captivity, were seen by him actively engaged in thread-spinning:—"Their usual mode of procedure was to crawl up the side of a glass vessel nearly to the surface of the water; they then gave one or two twisting motions, and crawled out on the under surface of the water, leaving a thread joining them to their point of departure. They then either sank slowly, remained floating, or sank about half way, where they stopped." The thread, the presence of which was easily demonstrated with a pin, was in most cases sufficiently strong to enable the observer to raise the animal to the surface, but not out of the water.[71]

Cypræidæ.

Our little Cowry (Cypræa europæa) makes considerable use of a thread, a fact first noticed by Charles Kingsley, who wrote to Gosse, in 1854, that he had seen the animal suspend itself from the under side of low-tide rocks by a glutinous thread an inch and more in length; in captivity, further, he saw it "float on the surface by means of a similar thread attached to a glutinous bubble."[72] According to a paper by Mr. L.St.G. Byne, the animal is occasionally seen at Teignmouth, hanging by its "byssus" on the rocks at low tide.[73] This statement, as the writer learns from Mr. Byne, is made on the authority of a reliable collector, who mentions, amongst other things, that on lifting a boulder he saw one of these molluscs hang from it by a thread 4-5 in. long. Mr. Hornell, from observations made presumably at Jersey, writes in an interesting manner on the same subject. In confinement in a tank, he says, the little animal frequently crawls foot-uppermost along the surface of the water, and occasionally may be seen to form a little disc of mucus, from which it lowers itself gently by a mucous thread till it hangs in mid-water, dangling in the fashion of a Spider at the end of its silken cord. "This habit of the Cowry is to be correlated," Mr. Hornell adds, "to that more familiar and natural one so readily verified by any observer who visits the low-tide caves and gullies where, amongst Sponges and Ascidians, this animal loves so to live. Here, when the tide recedes, Cowries more or less enveloped in their bright-coloured mantle robes are often seen passively hanging suspended from the gully's roof, or from points and jutting ledges, by a stout mucous thread."[74]

Cerithiidæ.

In this family we have notes on a Bittium, a Cerithiopsis, and a Cerithidea; general statements occur in the books also for Cerithium and Potamides, but these rise out of synonymy, the animals referred to being respectively Bittium and Cerithidea. Our little Bittium reticulatum,[75] according to Jeffreys, "crawls actively and quickly by means of its long foot, and occasionally suspends itself by a byssal filament to a bit of floating seaweed, or to the side of the vessel in which it is kept."[76] Cerithiopsis tubercularis, another little mollusc of our coasts (shell generally about ¼ in. long), resembles the Bittium in its active crawling habits. "When at rest," according to Jeffreys, "it spins a fine transparent thread, which issues from the opening in the centre of the foot-sole, its end being attached by the point of the foot to some foreign substance." The author, on one occasion, drew the shell up by the thread with a camel's-hair brush, and kept the creature thus suspended in the water for several seconds, the foot being doubled up.[77] Cerithidea obtusa,[78] which is a mollusc of good size, presents one of the most curious of the cases noticed in this paper. It lives in brackish water, in mangrove-swamps, and the mouths of rivers in Singapore and Borneo; sometimes it crawls on stones and leaves in the neighbourhood, and, according to the observations of A. Adams, it is not unfrequently found suspended by glutinous threads to boughs and the roots of the mangroves, as represented in fig. 6. Further, according to the same observer, "when the animal hybernates, it retracts itself into the shell, and brings its operculum to fit closely into the aperture, after having previously affixed sixty or seventy glassy, transparent, glutinous threads to the place of attachment, when they occupy the outer or right lip and extend half-way round the operculum."[79] Von Martens has observed that the attachment of this mollusc and of "Megalomastoma suspensum" (fig. 4) make a remarkable approach to the attachment of bivalves by a byssus,[80] but this remark, the writer presumes, refers merely to the appearance of the figures; for nothing appears to be known of the manner in which the threads are produced and attached. Adams's observations are referred to in nearly all the books, and figures based on his are found in Woodward and in Keferstein, that of the former having been repeated by Fischer and twice by Tryon.[81] Mr. Tye, who refers to Woodward, has by mistake attributed the observations to Cerithidea decollata,[82] an animal which does not appear to fix itself by threads, Dr. Gibbons having reported that large numbers seen by him on trunks of marsh trees in Natal were attached, not by threads, but by "a trifle of brittle mucus passing from the lip to the tree," a mode of attachment, as Dr. Gibbons says, resembling that of brackish water Littorinæ.[83]

Planaxidæ.

Planaxis has been listed among thread-making molluscs by Dr. Macdonald,[84] but the writer does not know on what authority.

Solariidæ.

According to Mr. Harper Pease, two forms of Torinia (Hawaiian Islands) "suspend themselves by strong gelatinous threads, one of which will sustain the weight of several shells, and can be drawn out four or five inches"; the creatures are found almost invariably upon branched coral.[85]

Pyramidellidæ.

Among the crowd of little conical-shelled molluscs of the genus Odostomia, the use of a thread has been observed by Jeffreys in Odostomia warreni, whose foot is remarkable from being forked at the extremity like the tail of a Swallow. The animal crept at the surface of the water like other gastropods, and one individual spun a delicate glutinous filament from the middle of the sole of the foot, and kept itself suspended for some time in the water, with the point of the shell downwards. 0. acicula, Jeffreys adds, has the same habit. Both animals are inhabitants of our own coasts.[86]

Eulimidæ.

Eulima intermedia, another inhabitant of our coasts, creeps at the surface, and, according to Jeffreys, "it remains suspended in that posture by means of a byssal thread, the operculum then closing the mouth of the shell";[87] statements, apparently applying to the genus generally, which occur in Fischer and in Tryon,[88] have their origin presumably in this observation.

Mitridæ.

The only representative of the Mitre-shells—and of a considerable number of surrounding families—of which we have any note is the little "Mitra saltata" Pease—probably the young of some larger Mitrid—a native of the shores of the islands of the Central Pacific. It is described as an elegant little mollusc, found living in hollows of coral-rock; and it is certainly a creature of remarkable habits. When disturbed (Mr. Pease found) it would skip five or six inches in a horizontal line, from one side of the cavity to the other, at the same time spinning out a very fine thread; and, when held in the hand, it would jump off, suspending itself by a thread to a distance of 2–3 ft.[89]

Pleurotomatidæ.

Another isolated note, the last we have to give, relates to Mangilia nebula,[90] a little mollusc of our own coasts. The animal is exceedingly active, and the Rev. R.N. Dennis, who placed specimens in a basin of sea-water, observed that they crawled to the edge and suspended themselves by a thread.[91]

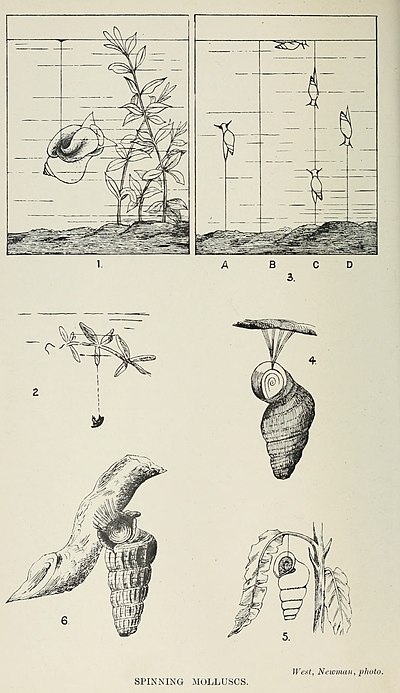

Explanation of Plate III.

Fig. 1.—A Water-Snail (Limnæa auricularia) hanging by a thread from the surface of the water in an aquarium. After Taylor, 'Monograph of the Land and Freshwater Mollusca of the British Isles,' i. (1899), p. 318 (fig. 610).

Fig. 2.—A fresh-water Limpet (Ancylus lacustris) using a thread. From a sketch by Prof. Cockerell.

Fig. 3.—Diagram illustrating the use of threads by aquatic Pulmonate Molluscs, based for the most part on observations recorded for Physa hypnorum, by Mr. G.S. Tye. The animal is ordinarily slightly lighter than water:—a, an individual crawling through the water towards the surface, leaving its locomotory mucus behind in the form of a thread, which retains the animal, and prevents its sudden rise to the surface; b, the animal at the surface, taking in a supply of air—the thread, having been continued as a floating slime-trail, is now attached to the surface; c, the animal returning by descending its thread; another individual is making use of the fixed thread for ascent. An upward journey (a) may be abandoned, the animal in that case returning upon its unattached thread, d.

Fig. 4.—"Megalomastoma suspensum," a land operculate of doubtful identity, at rest, suspended by a number of threads from a twig; probably much enlarged. After Swainson, 'Treatise on Malacology,' 1840, fig. 29; presumably from a sketch by Guilding.

Fig. 5.—Chondropoma dentatum, a land operculate, at rest, suspended by a short thread; slightly enlarged. After Binney, 'Terrestrial Air-breathing Mollusks of the United States,' ii. (1851), p. 347.

Fig. 6.—Cerithidea obtusa, a brackish-water, somewhat amphibious, operculate mollusc, at rest, suspended to a bough by a number of short threads. After A. Adams, 'Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Samarang: Mollusca,' 1848, pi. xiii. fig. 3 b.

- ↑ On the subject of the mucus-threads of Land-Slugs, I hope to give, in another place, details of observations and references; in addition to these molluscs, and to those now considered, the Mollusca-Pelecypoda (bivalves) are thread-makers and byssus-spinners, but I am unable at present to write of the habits of this class of Mollusca. For help in preparing the present paper, and in other tasks, I am much indebted to the courteous and continued co-operation of my friend Mr. G.K. Gude.

- ↑ Collinge, Zool. (3), xiv. (1890), p. 468.

- ↑ Microcystis conula.

- ↑ Garrett, 'Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia' (2), viii. (1881), pp. 383–4; ix. (1884), p. 21.

- ↑ Tye, 'Quarterly Journal of Conchology,' i. (1878), p. 412.

- ↑ Warington, 'Annals and Magazine of Natural History' (2), x. (1852), pp. 273–6; (2), xiv. (1854), p. 366; Zool. x. (1852), pp. 3634-5; xiii. (1855), p. 4533; Tye, Hardwicke's 'Science-Gossip,' 1874, pp. 49–52; 'Quarterly Journal of Conchology,' i. (1878), pp. 401–15.

- ↑ Taylor, 'Monograph of the Land and Freshwater Mollusca of the British Isles,' i. (1899), pp. 318–9.

- ↑ The locomotory mucus, besides serving for ordinary crawling on solid bodies (when it is left behind as an attached trail), and for crawling through the water (when it is left in the form of a thread), serves also for a similar crawling progression at the surface of water, the animal, foot uppermost, now leaving the mucus in its path in the form of a floating trail. Limnæids and Physids are often seen thus crawling at the surface of the water of aquaria and of ponds; and the habit, which is common to many gastropods of all orders, was long a puzzle to naturalists. Alder and Hancock (1), however, who studied it in Nudibranchia (Sea-Slugs), saw the movements of the foot-sole to be those of ordinary crawling, and recognized the fact that the creature's progress was caused by these movements against the mucus which it emits and leaves in its track. The animal thus crawls along the floating mucus, the authors maintain, just as it does on the attached mucus which it sheds on its path on a solid body. Willem (2), it may be added, evidently unacquainted with the work of Alder and Hancock, has confirmed their conclusions from observations on Limnæa and Planorbis:—"Les Gastéropodes d'eau douce," he says, "pour glisser renversés à la surface de l'eau, commencent par prendre appui sur la mince pellicule superficielle qui recouvre toujours l'eau des mares et des étangs; puis ils rampent à la face inferieure d'un mince tapis de mucus que leur pied'sécrète au fur et à mesure de la progression. Cette locomotion," the author adds, "ne diffère de la locomotion sur les corps solides qu'en ce sens que, lors de la locomotion aquatique, le Mollusque est réduit à tirer parti de la rigidité de la seule trainée de mucine, tandis que, dans l'autre cas, la trainée est elle-même collée à une surface solide." By blowing lycopodium powder on the surface of the water, Willem clearly demonstrated the presence of the floating trail; the grains, gathering into groups on the rest of the surface, adhered evenly to the band of mucus, and showed it distinctly. Under natural conditions this floating trail is usually invisible, but not invariably. We find, for instance, that Mr. Crowther (3), passing along a disused canal connecting bends of the Calder, distinctly saw the tracks of Limnæa stagnalis at the surface of the clear water, in the sunshine, with a darkened background of black mud; they appeared as whitish iridescent paths of mucus, 6–8 ft. long, and half an inch wide, mostly straight, and often crossing one another nearly at right angles. (1) Alder and Hancock, 'Monograph of the British Nudibranchiate Mollusca,' 1845–55, pp. 20–1; (2) Willem, "Note sur le procédé employé par les Gastéropodes d'eau douce pour glisser à la surface du liquide," 'Bulletins de l'Académie Royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique' (3), xv. (1888), pp. 421–30; (3) Crowther, "Mucous Tracks of Limnæa stagnalis," 'Journal of Conchology,' viii. (1896), p. 230; and see also Taylor, tom. cit. p. 316, fig. 607.

- ↑ Limnæa glutinosa.

- ↑ Limnæa glutinosa.

- ↑ Tate, 'Land and Fresh-water Mullusks of Great Britain,' 1866, p. 198.

- ↑ Fierke, 'Journal of Conchology,' vi. (1890), p. 253.

- ↑ Musson, 'Land and Fresh-water Shells of Nottinghamshire,' 1886, MS.

- ↑ Planorbis lineatus.

- ↑ Cockerell, "Segmentina lineata, Walker, a Thread-spinner," 'Zoologist' (3), ix. (1885), p. 267.

- ↑ Clark, 'Annals and Magazine of Natural History' (2), xv. (1855), p. 285.

- ↑ Taylor, "Ancylus lacustris, a thread-spinner," 'Journal of Conchology,' iv. (1883), p. 127.

- ↑ Bulla fontinalis.

- ↑ Montagu, 'Testacea Britannica,' 1803, p. 227.

- ↑ Jeffery, 'Journal of Conchology,' iii. (1882), pp. 310–1.

- ↑ Musson, l.c.

- ↑ Bate, 'Annals and Magazine of Natural History' (2), xv. (1855), p. 131.

- ↑ Alder and Hancock, op. cit. p. 21.

- ↑ P. quadrilineata v. nonlineata.

- ↑ Thompson, 'Annals of Natural History,' v. (1840), p. 92.

- ↑ Doris amabilis.

- ↑ Kelaart, 'Annals and Magazine of Natural History' (3), iii. (1859), pp. 294–5.

- ↑ Sinel, 'Journal of Marine Zoology,' i. (1894), p. 32.

- ↑ Eolis coronata.

- ↑ Hornell, 'Journal of Marine Zoology,' ii. (1896), p. 59.

- ↑ Aplysiopterus viridis.

- ↑ Gray, 'Annals and Magazine of Natural History' (3), iv. (1859), pp. 239–40.

- ↑ Johnston, 'Catalogue of the British Non-parasitical Worms in the British Museum,' 1865, p. 12.

- ↑ Dalyell, 'The Powers of the Creator displayed in the Creation,' ii. (1853), pp. 115–6.

- ↑ Warington, 1854, l.c.

- ↑ Tye, 1874, l.c.; 1878, l.c.

- ↑ Petit de la Saussaye (quoting Lucas), 'Journal de Conchyliologie ' iii. (1852), p. 100.

- ↑ Swainson, 'Treatise on Malacology,' 1840, p. 186.

- ↑ Guilding, 'Loudon's Magazine of Natural History,' ix. (1836), p. 195.

- ↑ Adamsiella aripensis.

- ↑ Guppy, 'Annals and Magazine of Natural History' (3), xvii. (1866), p. 45; 'Proceedings of the Scientific Association of Trinidad,' i. (1866), p. 31.

- ↑ Cyclostoma dentatum.

- ↑ Binney, 'Terrestrial Air-breathing Mollusks of the United States,' ii. (1851), pp. 347–9; and see also W. G. Binney, 'Land and Freshwater Shells of North America,' 1865, pp. 96–7, fig. 194 (Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, vii.); and Tryon, 'American Journal of Conchology,' iv. (1868), p. 11; pl. xviii. fig. 15.

- ↑ Gibbons, 'Journal of Conchology.' ii. (1879), p. 134; and in Tye, 'Quarterly Journal of Conchology,' i. (1878), p. 412.

- ↑ Gibbons, 'Quarterly Journal of Conchology,' i. (1878), pp. 411–2; and Tye, l.c.

- ↑ Woodward, 'Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London,' 1859, p. 204; and 'Annals and Magazine of Natural History' (3), iv. (1859), p. 320.

- ↑ Gibbons, 1878, tom. cit. p. 339; 1879, l.c.

- ↑ Gray, 'Annals and Magazine of Natural History' (2), ix. (1852), p. 216.

- ↑ Gibbons, 1878, l.c.; 1879, l.c.; Jeffreys, 'British Conchology,' iii. (1865), p. 363; Bouchard-Chantereaux, 'Mémoires et Notices de la Société d'Agriculture, du Commerce et des Arts, de Boulogne-sur-Mer, 1835, pp. 155–7; Gray, 'Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London,' 1833, p. 116; A. d'Orbigny, 'Histoire Naturelle des Iles Canaries: Mollusques,' 1839, p. 79.

- ↑ Jeffreys, tom. cit. p. 343.

- ↑ Gray, 'Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London,' 1833, p. 116.

- ↑ Jeffreys, op. cit., iv. (1867), p. 1.

- ↑ Jeffreys, tom. cit., pp. 25, 26.

- ↑ R. striatula.

- ↑ Jeffreys, tom. cit., pp. 6, 10, 20, 32, 41, 43, 44.

- ↑ R. striatula.

- ↑ Tomlin, 'British Naturalist,' iii. (1893), p. 123.

- ↑ Jeffreys, tom. cit., p. 57.

- ↑ Lindström, 'Om Gotlands nutida mollusker,' 1868, p. 26.

- ↑ Tye, 1874, l.c.; 1878, l.c.

- ↑ Jeffreys, tom. cit., p. 66.

- ↑ Jeffreys, tom. cit., p. 60.

- ↑ Rang, "Notice sur le Litiope (Litiopa), genre nouveau de Mollusque gastéropode," 'Annales des Sciences Naturelles,' xvi. (1829), pp. 303–7; and 'Manuel de l'Histoire Naturelle des Mollusques,' 1829, pp. 26, 197, 198.

- ↑ Bélanger, "Sur les Litiopes (Litiopa, Rang), ou Bombyxins (Bombyxinus, Bélanger)," Lesson's 'Illustrations de Zoologie,' 1831: appendix (1833?).

- ↑ Kiener, "Quelques Observations sur le genre Litiope de M. Rang," 'Annales des Sciences Naturelles,' xxx. (1833), pp. 221–4.

- ↑ Eydoux and Souleyet, "Observations sur le genre Litiope," 'Annales Françaises et Etrangeres d'Anatomie et de Physiologie,' iii. (1839), pp. 252–6.

- ↑ The author refers also to a bundle of weed, containing a quantity of eggs, supposed, no doubt erroneously, to be those of Litiopa. The eggs were united by numerous threads similar to those of the mollusc; each egg was attached by a particular thread, and the whole mass was so strongly fastened together that it was with difficulty that a part was detached. This structure, it can hardly be doubted, was the "nest" of the little Gulf-weed Fish, Pterophryne.

- ↑ Johnston, 'Introduction to Conchology,' 1850, p, 134; with references to Rang and Kiener.

- ↑ A. Adams, 'Annals and Magazine of Natural History' (3), x. (1862), pp. 293-5, 419.

- ↑ Laurent, 'Extraits des Procès-Verbaux des Séances de la Société Philomatique de Paris,' 1841, pp. 118–9.

- ↑ Boycott, "Valvata piscinalis as a Spinner," 'Science Gossip' (n.s.), ii. (1895), p. 82.

- ↑ 'Charles Kingsley; his Letters and Memories of his Life,' edited by his Wife, ed. 3, i. (1877), p. 408.

- ↑ Byne, 'Journal of Conchology,' vii. (1893), p. 187.

- ↑ Hornell, 'Journal of Marine Zoology,' ii. (1896), pp. 59–61.

- ↑ Cerithium reticulatum.

- ↑ Jeffreys, tom. cit. p. 260.

- ↑ Ibid. p. 268.

- ↑ Cerithium truncatum, C. obtusum.

- ↑ A. Adams, 'Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Samarang: Mollusca,' 1848, pp. 43–4; and see also 'Narrative of the Voyage,' ii. (1848), pp. 389, 509; 'Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London,' 1847, pp. 21–2; and 'Annals and Magazine of Natural History,' xix. (1847), pp. 413–4.

- ↑ E. v. Martens, 'Zoologischer Anzeiger,' i. (1878), p. 251.

- ↑ Woodward, 'Manual of the Mollusca,' 1851, fig. 78: Keferstein, 'Bronn's Klassen und Ordnungen des Thier-reichs,' iii. (1862–6), pl. lxxxii. fig. 9; Fischer, 'Manuel de Conchyliologie,' 1884, fig. 449; Tryon, 'Structural and Systematic Conchology,' ii. (1883), pl. lxx. fig. 73; 'Manual of Conchology,' ix. (1887), pl. xix. fig. 6.

- ↑ Tye, 'Quarterly Journal of Conchology,' i. (1878), p. 409.

- ↑ Gibbons, 'Journal of Conchology,' ii. (1879), p. 134.

- ↑ Macdonald, 'Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society': Zoology, v. (1861), p. 209.

- ↑ Pease, 'American Journal of Conchology,' v. (1870), p. 81.

- ↑ Jeffreys, 'Annals and Magazine of Natural History' (4), ii. (1868), p. 279; British Association Reports, 1868, p. 233; op. cit. v. (1869), p. 212.

- ↑ Jeffreys, op. cit. iv. (1867), p. 204.

- ↑ Fischer, 'Manuel de Conchyliologie,' 1885, p. 782; Tryon, 'Manual of Conchology,' viii. (1886), p. 259.

- ↑ Pease, 'Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London,' 1865, pp. 512–3; and see Garrett, 'Journal of Conchology,' iii. (1880), p. 71.

- ↑ Pleurotoma nebula.

- ↑ Dennis, in Jeffreys, tom. cit. p. 386.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1929.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1948, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 75 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse