Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile/Volume 1/Book 1/Chapter 3

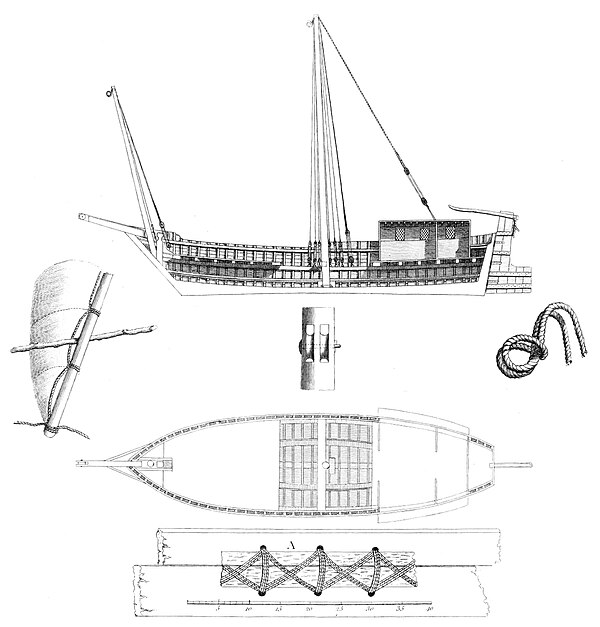

Canja under Sail.

CHAP. III.

Leaves Cairo—Embarks on the Nile for Upper Egypt—Visits Metrahenny and Mohannan—Reasons for supposing this the Situation of Memphis.

Having now provided every thing necessary, and taken a rather melancholy leave of our very indulgent friends, who had great apprehensions that we should never return; and fearing that our stay till the very excessive heats were past, might involve us in another difficulty, that of missing the Etesian winds, we secured a boat to carry us to Furshout, the residence of Hamam, the Shekh of Upper Egypt.

This sort of vessel is called a Canja, and is one of the most commodious used on any river, being safe, and expeditious at the same time, though at first sight it has a strong appearance of danger.

That on which we embarked was about 100 feet from stern to stem, with two masts, main and foremast, and two monstrous Latine sails; the main-sail yard being about 200 feet in length.

The structure of this vessel is easily conceived, from the draught, plan, and section. It is about 30 feet in the beam, and about 90 feet in keel.

The keel is not straight, but a portion of a parabola whose curve is almost insensible to the eye. But it has this good effect in sailing, that whereas the bed of the Nile, when the water grows low, is full of sand banks under water, the keel under the stem, where the curve is greatest, first strikes upon these banks, and is fast, but the rest of the ship is afloat; so that by the help of oars, and assistance of the stream, furling the sails, you get easily off; whereas, was the keel straight, and the vessel going with the pressure of that immense main-sail, you would be so fast upon the bank as to lie there like a wreck for ever.

This yard and sail is never lowered. The sailors climb and furl it as it stands. When they shift the sail, they do it with a thick stick like a quarter staff, which they call a noboot, put between the lashing of the yard and the sail; they then twist this stick round till the sail and yard turn over to the side required.

When I say the yard and sail are never lowered, I mean while we are getting up the stream, before the wind; for, otherwise, when the vessel returns, they take out the mast, lay down the yards, and put by their sails, so that the boat descends like a wreck broadside forwards; otherwise, being so heavy a-loft, were she to touch with her stem going down the stream, she could not fail to carry away her masts, and perhaps be staved to pieces.

The cabin has a very decent and agreeable dining-room about twenty feet square, with windows that have close and latticed shutters, so that you may open them at will in the day-time, and enjoy the freshness of the air; but great care must be taken to keep these shut at night.

Section of the Canja.

They are not very fond, I am told, of meddling with vessels whereon they see Franks, or Europeans, because by them some have been wounded with fire-arms.

The attempts are generally made when you are at anchor, or under weigh, at night, in very moderate weather; but oftenest when you are falling down the stream without masts; for it requires, strength, vigour, and skill, to get aboard a vessel going before a brisk wind; though indeed they are abundantly provided with all these requisites.

Behind the dining-room (that is, nearer the stern,) you have a bed-chamber ten feet long, and a place for putting your books and arms. With the latter we were plentifully supplied, both with those of the useful kind, and those (such as large blunderbusses,) meant to strike terror. We had great abundance of ammunition likewise, both for our defence and sport.

With books we were less furnished, yet our library was chosen, and a very dear one; for, finding how much my baggage was increased by the accession of the large quadrant and its foot, and Dolland's large achromatic telescope, I began to think it folly to load myself more with things to be carried on mens shoulders through a country full of mountains, which it was very doubtful whether I should get liberty to enter, much more be able to induce savages to carry these incumbrances for me.

To reduce the bulk as much as possible, after considering in my mind what were likeliest to be of service to me in the countries through which I was passing, and the several inquiries I was to make, I fell, with some remorse, upon garbling my library, tore out all the leaves which I had marked for my purpose, destroyed some editions of very rare books, rolling up the needful, and tying them by themselves. I thus reduced my library to a more compact form.

It was December 12th when I embarked on the Nile at Bulac, on board the Canja already mentioned, the remaining part of which needs no description, but will be understood immediately upon inspection.

At first we had the precaution to apply to our friend Risk concerning our captain Hagi Hassan Abou Cuffi, and we obliged him to give his son Mahomet in security for his behaviour towards us. Our hire to Furshout was twenty-seven patakas, or about L.6:15:0 Sterling.

There was nothing so much we desired as to be at some distance from Cairo on our voyage. Bad affairs and extortions always overtake you in this detestable country, at the very time when you are about to leave it.

The wind was contrary, so we were obliged to advance against the stream, by having the boat drawn with a rope.

We were surprised to see the alacrity with which two young Moors bestirred themselves in the boat, they supplied the place of masters, companions, pilots, and seamen to us.Our Rais had not appeared, and I did not augur much good from the alacrity of these Moors, so willing to proceed without him.

However, as it was conformable to our own wishes, we encouraged and cajoled them all we could. We advanced a few miles to two convents of Cophts, called Deireteen[1].

Here we stopped to pass the night, having had a fine view of the Pyramids of Geeza and Saccara, and being then in sight of a prodigious number of others built of white clay, and stretching far into the desert to the south-west.

Two of these seemed full as large as those that are called the Pyramids of Geeza. One of them was of a very extraordinary form, it seemed as if it had been intended at first to be a very large one, but that the builder's heart or means had failed him, and that he had brought it to a very mis-shapen disproportioned head at last.

We were not a little displeased to find, that, in the first promise of punctuality our Rais had made, he had disappointed us by absenting himself from the boat. The fear of a complaint, if we remained near the town, was the reason why his servants had hurried us away; but being now out of reach, as they thought, their behaviour was entirely changed; they scarce deigned to speak to us, but smoked their pipes, and kept up a conversation bordering upon ridicule and insolence.

On the side of the Nile, opposite to our boat, a little farther to the south, was a tribe of Arabs encamped.

These are subject to Cairo, or were then at peace with its government. They are called Howadat, being a part of the Atouni, a large tribe that possesses the Isthmus of Suez, and from that go up between the Red Sea and the mountains that bound the east part of the Valley of Egypt. They reach to the length of Cosseir, where they border upon another large tribe called Ababdé, which extends from thence up into Nubia.

Both these are what were anciently called Shepherds, and are now constantly at war with each other.

The Howadat are the same that fell in with Mr Irvine[2] in these very mountains, and conducted him so generously and safely to Cairo. Though little acquainted with the manners, and totally ignorant of the language of his conductors, he imagined them to be, and calls them by no other name, than "the Thieves."

One or two of these straggled down to my boat to seek tobacco and coffee, when I told them, if a few decent men among them would come on board, I should make them partakers of the coffee and tobacco I had. Two of them accepted the invitation, and we presently became great friends.

I remembered, when in Barbary, living with the tribes of Noile and Wargumma (two numerous and powerful clans of Arabs in the kingdom of Tunis) that the Howadat, or Atouni, the Arabs of the Isthmus of Suez, were of the same family and race with one of them.

I even had marked this down in my memorandum-book, but it happened not to be at hand; and I did not really remember whether it was to the Noile or Wargumma they were friends, for these two are rivals, and enemies, so in a mistake there was danger. I, however, cast about a little to discover this if possible; and soon, from discourse and circumstances that came into my mind, I found it was the Noile to whom these people belonged; so we soon were familiar, and as our conversation tallied so that we found we were true men, they got up and insisted on fetching one of their Shekhs.

I told them they might do so if they pleased; but they were first bound to perform me a piece of service, to which they willingly and readily offered themselves. I desired, that, early next morning, they would have a boy and horse ready to carry a letter to Risk, Ali Bey's secretary, and I would give him a piaster upon bringing back the answer.

This they instantly engaged to perform, but no sooner were they gone a-shore, than, after a short council held together, one of our laughing boat-companions stole off on foot, and, before day, I was awakened by the arrival of our Rais Abou Cuffi, and his son Mahomet.

Abou Cuffi was drunk, though a Sherriffe, a Hagi, and half a Saint besides, who never tasted fermented liquor, as he told me when I hired him.—The son was terrified out of his wits. He said he should have been impaled, had the messenger arrived; and, seeing that I fell upon means to keep open a correspondence with Cairo, he told me he would not run the risk of being surety, and of going back to Cairo to answer for his father's faults, least, one day or another, upon some complaint of that kind, he might be taken out of his bed and bastinadoed to death, without knowing what his offence was.

An altercation ensued; the father declined staying upon pretty much the same reasons, and I was very happy to find that Risk had dealt roundly with them, and that I was master of the string upon which I could touch their fears.

They then both agreed to go the voyage, for none of them thought it very safe to stay; and I was glad to get men of some substance along with me, rather than trust to hired vagabond servants, which I esteemed the two Moors to be.

As the Shekh of the Howadat and I had vowed friendship, he offered to carry me to Cosseir by land, without any expence, and in perfect safety, thinking me diffident of my boatmen, from what had passed.

I thanked him for this friendly offer, which I am persuaded I might have accepted very safely, but I contented myself with desiring, that one of the Moor servants in the boat should go to Cairo to fetch Mahomet Abou Cuffi's son's cloaths, and agreed that I should give five patakas additional hire for the boat, on condition that Mahomet should go with us in place of the Moor servant, and that Abou Cuffi, the father and saint (that never drank fermented liquors) should be allowed to sleep himself sober, till his servant the Moor returned from Cairo with his son's cloaths.In the mean time, I bargained with the Shekh of the Howadat to furnish me with horses to go to Metrahenny or Mohannan, where once he said Mimf had stood, a large city, the capital of all Egypt.

All this was executed with great success. Early in the morning the Shekh of the Howadat had passed at Miniel, where there is a ferry, the Nile being very deep, and attended me with five horsemen and a spare horse for myself, at Metrahenny, south of Miniel, where there is a great plantation of palm-trees.

The 13th, in the morning about eight o'clock, we let out our vast sails, and passed a very considerable village called Turra, on the east side of the river, and Shekh Atman, a small village, consisting of about thirty houses, on the west.

The mountains which run from the castle to the eastward of south-east, till they are about five miles distant from the Nile east and by north of this station, approach again the banks of the river, running in a direction south and by west, till they end close on the banks of the Nile about Turra.

The Nile here is about a quarter of a mile broad; and there cannot be the smallest doubt, in any person disposed to be convinced, that this is by very far [3] the narrowest part of Egypt yet seen. For it certainly wants of half-a-mile between the foot of the mountain and the Libyan shore, which cannot be said of any other part of Egypt we had yet come to; and it cannot be better described than it is by [4] Herodotus; and "again, opposite to the Arabian side, is another stony mountain of Egypt towards Libya, covered with sand, where are the Pyramids."

As this, and many other circumstances to be repeated in the sequel, must naturally awaken the attention of the traveller to look for the ancient city of Memphis here, I left our boat at Shekh Atman, accompanied by the Arabs, pointing nearly south. We entered a large and thick wood of palm-trees, whose greatest extension seemed to be south by east. We continued in this course till we came to one, and then to several large villages, all built among the plantation of date-trees, so as scarce to be seen from the shore.

These villages are called Metrahenny, a word from the etymology of which I can derive no information, and leaving the river, we continued due west to the plantation that is called Mohannan, which, as far as I know, has no signification either.

All to the south, in this desert, are vast numbers of Pyramids; as far as I could discern, all of clay, some so distant as to appear just in the horizon.Having gained the western edge of the palm-trees at Mohannan, we have a fair view of the Pyramids at Geeza, which lie in a direction nearly S.W. As far as I can compute the distance, I think about nine miles, and as near as it was possible to judge by sight, Metrahenny, Geeza, and the center of the three Pyramids, made an Isosceles triangle, or nearly so.

I asked the Arab what he thought of the distance? whether it was farthest to Geeza, or the Pyramids? He said, they were sowah, sowah, just alike, he believed; from Metrahenny to the Pyramids perhaps might be farthest, but he would much sooner go it, than along the coast to Geeza, because he should be interrupted by meeting with water.

All to the west and south of Mohannan, we saw great mounds and heaps of rubbish, and calishes that were not of any length, but were lined with stone, covered and choked up in many places with earth.

We saw three large granite pillars S.W. of Mohannan, and a piece of a broken chest or cistern of granite; but no obelisks, or stones with hieroglyphics, and we thought the greatest part of the ruins seemed to point that way, or more southerly.

These, our conductor said, were the ruins of Mimf, the ancient seat of the Pharaohs kings of Egypt, that there was another Mimf, far down in the Delta, by which he meant Menouf, below Terrane and Batn el Baccara[5].

Perceiving now that I could get no further intelligence, I returned with my kind guide, whom I gratified for his pains, and we parted content with each other.

In the sands I saw a number of hares. He said, if I would go with him to a place near Faioume, I should kill half a boat-load of them in a day, and antelopes likewise, for he knew where to get dogs; mean-while he invited me to shoot at them there, which I did not choose; for, passing very quietly among the date-trees, I wished not to invite further curiosity.

All the people in the date villages seemed to be of a yellower and more sick-like colour, than any I had ever seen; besides, they had an inanimate, dejected, grave countenance, and seemed rather to avoid, than wish any conversation.

It was near four o'clock in the afternoon when we returned to our boatmen. By the way we met one of our Moors, who told us they had drawn up the boat opposite to the northern point of the palm-trees of Metrahenny.

My Arab insisted to attend me thither, and, upon his arrival, I made him some trifling presents, and then took my leave.

In the evening I received a present of dry dates, and some sugar cane, which does not grow here, but had been brought to the Shekh by some of his friends, from some of the villages up the river.

The learned Dr Pococke, as far as I know, is the first European traveller that ventured to go out of the beaten path, and look for Memphis, at Metrahenny and Mohannan.

Dr Shaw, who in judgment, learning, and candour, is equal to Dr Pococke, or any of those that have travelled into Egypt, contends warmly for placing it at Geeza.

Mr Niebuhr, the Danish traveller, agrees with Dr Pococke. I believe neither Shaw nor Niebuhr were ever at Metrahenny, which Dr Pococke and myself visited; though all of us have been often enough at Geeza, and I must confess, strongly as Dr Shaw has urged his arguments, I cannot consider any of the reasons for placing Memphis at Geeza as convincing, and very few of them that do not go to prove just the contrary in favour of Metrahenny.

Before I enter into the argument, I must premise, that Ptolemy, if he is good for any thing, if he merits the hundredth part of the pains that have been taken with him by his commentators, must surely be received as a competent authority in this case.

The inquiry is into the position of the old capital of Egypt, not fourscore miles from the place where he was writing, and immediately in dependence upon it. And therefore, in dubious cases, I shall have no doubt to refer to him as deserving the greatest credit.

Dr Pococke [6] says, that the situation of Memphis was at Mohannan, or Metrahenny, because Pliny says the [7] Pyramids were between Memphis and the Delta, as they certainly are, if Dr Pococke is right as to the situation of Memphis.Dr Shaw does not undertake to answer this direct evidence, but thinks to avoid its force by alledging a contrary sentiment of the same Pliny, "that the Pyramids [8] lay between Memphis and the Arsinoite nome, and consequently, as Dr Shaw thinks, they must be to the westward of Memphis."

Memphis, if situated at Metrahenny, was in the middle of the Pyramids, three of them to the N.W. and above three-score of them to the south.

When Pliny said that the Pyramids were between Memphis and the Delta, he meant the three large Pyramids, commonly called the Pyramids of Geeza.

But in the last instance, when he spoke of the Pyramids of Saccara, or that great multitude of Pyramids southward, he said they were between Memphis and the Arsinoite nome; and so they are, placing Memphis at Metrahenny.

For Ptolemy gives Memphis 29° 50′ in latitude, and the Arsinoite nome 29° 30′ and there is 8′ of longitude betwixt them. Therefore, the Arsinoite nome cannot be to the west, either of Geeza or Metrahenny; the Memphitic nome extends to the westward, to that part of Libya called the Scythian Region; and south of the Memphitic nome is the Arsinoite nome, which is bounded on the westward by the same part of Libya.

To prove that the latter opinion of Pliny should outweigh the former one, Dr Shaw cites [9]Diodorus Siculus, who says Memphis was most commodiously situated in the very key, or inlet of the country, where the river begins to divide itself into several branches, and forms the Delta.

I cannot conceive a greater proof of a man being blinded by attachment to his own opinion, than this quotation. For Memphis was in lat. 29° 50′, and the point of the Delta was in 30°, and this being the latitude of Geeza, it cannot be that of Memphis. That city must be sought for ten or eleven miles farther south.

If, as Dr Shaw supposes, it was nineteen miles round, and that it was five or six miles in breadth, its greatest breadth would probably be to the river. Then 10 and 6 make 16, which will be the latitude of Metrahenny, according to [10] Dr Shaw's method of computation.

But then it cannot be said that Geeza is either in the key or inlet of the country; all to the westward of Geeza is plain, and desert, and no mountain nearer it on the other side than the castle of Cairo.

Dr Shaw[11] thinks that this is further confirmed by Pliny's saying that Memphis was within fifteen miles of the Delta. Now if this was really the case, he suggests a plain reason, if he relies on ancient measures, why Geeza, that is only ten miles, cannot be Memphis.If a person, arguing from measures, thinks he is intitled to throw away or add, the third part of the quantity that he is contending for, he will not be at a great stress to place these ancient cities in what situation he pleases.

Nor is it fair for Dr Shaw to suppose quantities that never did exist; for Metrahenny, instead of [12] forty, is not quite twenty-seven miles from the Delta; such liberties would confound any question.

The Doctor proceeds by saying, that heaps of ruins [13] alone are not proof of any particular place; but the agreeing of the distances between Memphis and the Delta, which is a fixed and standing boundary, lying at a determinate distance from Memphis, must be a proof beyond all exception[14].

If I could have attempted to advise Dr Shaw, or have had an opportunity of doing it, I would have suggested to him, as one who has maintained that all Egypt is the gift of the Nile, not to say that the point of the Delta is a standing and determined boundary that cannot alter. The inconsistency is apparent, and I am of a very contrary opinion.

Babylon, or Cairo, as it is now called, is fixed by the Calish or Amnis Trajanus passing through it. Ptolemy [15] says so, and Dr Shaw says that Geeza was opposite to Cairo, or in a line east and west from it, and is the ancient Memphis.Now, if Babylon is lat. 30°, and so is Geeza, they may be opposite to one another in a line of east and west. But if the latitude of Memphis is 29° 50′, it cannot be at Geeza, which is opposite to Babylon, but ten miles farther south, in which case it cannot be opposite to Babylon or Cairo. Again, if the point of the Delta be in lat. 30°, Babylon, or Cairo, 30°, and Geeza be 30°, then the point of the Delta cannot be ten miles from Cairo or Babylon, or ten miles from Geeza.

It is ten miles from Geeza, and ten miles from Babylon, or Cairo, and therefore the distances do not agree as Dr Shaw says they do; nor can the point of the Delta, as he says, be a permanent boundary consistently with his own figures and those of Ptolemy, but it must have been washed away, or gone 10′ northward; for Babylon, as he says, is a certain boundary fixed by the Amnis Trajanus, and, supposing the Delta had been a fixed boundary, and in lat. 30°, then the distance of fifteen miles would just have made up the space that Pliny says was between that point and Memphis, if we suppose that great city was at Metrahenny.

I shall say nothing as to his next argument in relation to the distance of Geeza from the Pyramids; because, making the same suppositions, it is just as much in favour of one as of the other.

His next argument is from [16] Herodotus, who says, that Memphis lay under the sandy mountain of Libya, and that this mountain is a stony mountain covered with sand, and is opposite to the Arabian mountain.

Now this surely cannot be called Geeza; for Geeza is under no mountain, and the Arabian mountain spoken of here is that which comes close to the shore at Turra.

Diodorus says, it was placed in the straits or narrowest part of Egypt; and this Geeza cannot be so placed, for, by Dr Shaw's own confession, it is at least twelve miles from Geeza to the sandy mountain where the Pyramids stand on the Libyan side; and, on the Arabian side, there is no mountain but that on which the castle of Cairo stands, which chain begins there, and runs a considerable way into the desert, afterwards pointing south-west, till they come so near to the eastern shore as to leave no room but for the river at Turra; so that, if the cause is to be tried by this point only, I am very confident that Dr Shaw's candour and love of truth would have made him give up his opinion if he had visited Turra.

The last authority I shall examine as quoted by Dr Shaw, is to me so decisive of the point in question, that, were I writing to those only who are acquainted with Egypt, and the navigation of the Nile, I would not rely upon another.

Herodotus[17] says, "At the time of the inundation, the Egyptians do not sail from Naucratis to Memphis by the common channel of the river, that is Cercasora, and the point of the Delta, but over the plain country, along the very side of the Pyramids."Naucratis was on the west side of the Nile, about lat. 30° 30′. let us say about Terrane in my map. They then sailed along the plain, out of the course of the river, upon the inundation, close by the Pyramids, whatever side they pleased, till they came to Metrahenny, the ancient Memphis.

The Etesian wind, fair as it could blow, forwarded their course whilst in this line. They went directly before the wind, and, if we may suppose, accomplished the navigation in a very few hours; having been provided with those barks, or canjas, with their powerful sails, which I have already described, and, by means of which, they shortened their passage greatly, as well as added pleasure to it.

But very different was the case if the canja was going to Geeza.

They had nothing to do with the Pyramids, nor to come within three leagues of the Pyramids; and nothing can be more contrary, both to fact and experience, than that they would shorten their voyage by sailing along the side of them; for the wind being at north and north-west as fair as possible for Geeza, they had nothing to do but to keep as direct upon it as they could lie. But if, as Dr Shaw thinks, they made the Pyramids first, I would wish to know in what manner they conducted their navigation to come down upon Geeza.

Their vessels go only before the wind, and they had a strong steady gale almost directly in their teeth.

They had no current to help them; for they were in still water; and if they did not take down their large yards and sails, they were so top-heavy, the wind had so much purchase upon them above, that there was no alternative, but, either with sails or without, they must make for Upper Egypt; and there, entering into the first practicable calish that was full, get into the main stream.

But their dangers were not still over, for, going down with a violent current, and with their standing rigging up, the moment they touched the banks, their masts and yards would go overboard, and, perhaps, the vessel stave to pieces.

Nothing would then remain, but for safety's sake to strike their masts and yards, as they always do when they go down the river; they must lie broadside foremost, the strong wind blowing perpendicular on one side of the vessel, and the violent current pushing it in a contrary direction on the other; while a man, with a long oar, balances the advantage the wind has of the stream, by the hold it has of the cabin and upper works.

This would most infallibly be the case of the voyage from Naucratis, unless in striving to sail by tacking, (a manœuvre of which their vessel is not capable) their canja should overset, and then they must all perish.

If Memphis was Metrahenny, I believe most people who had leisure would have tried the voyage from Naucratis by the plain. They would have been carried straight from north to south. But Dr Shaw is exceedingly mistaken, if he thinks there is any way so expeditious as going up the current of the river. As far as I can guess, from ten to four o'clock we seldom went less than eight miles in the hour, against a current that surely ran more than six. This current kept our vessel stiff, whilst the monstrous sail forced us through with a facility not to be imagined.

Dr Shaw, to put Geeza and Memphis perfectly upon a footing, says[18], that there were no traces of the city now to be found, from which he imagines it began to decay soon after the building of Alexandria, that the mounds and ramparts which kept the river from it were in process of time neglected, and that Memphis, which he supposes was in the old bed of the river about the time of the Ptolemies, was so far abandoned, that the Nile at last got in upon it, and overflowing its old ruins, great part of the best of which had been carried first to build the city of Alexandria, that the mud covered the rest, so that no body knew what was its true situation. This is the opinion of Dr Pococke, and likewise of M. de Maillet.

The opinion of these two last-mentioned authors, that the ruins and situation of Memphis are now become obscure, is certainly true; the foregoing dispute is a sufficient evidence of this.

But I will not suffer it to be said, that, soon after the building of Alexandria, or in the time of the Ptolemies, this was the case, because Strabo [19] says, that when he was in Egypt, Memphis, next to Alexandria, was the most magnificent city in Egypt.

It was called the Capital [20] of Egypt, and there was entire a temple of Osiris; the Apis (or sacred ox) was kept and worshipped there. There was likewise an apartment for the mother of that ox still standing, a temple of Vulcan of great magnificence, a large [21] circus, or space for fighting bulls; and a great colossus in the front of the city thrown down: there was also a temple of Venus, and a serapium, in a very sandy place, where the wind heaps up hills of moving sand very dangerous to travellers, and a number of [22] sphinxes, (of some only their heads being visible) the others covered up to the middle of their body.

In the [23] front of the city were a number of palaces then in ruins, and likewise lakes. These buildings, he says, stood formerly upon an eminence; they lay along the side of the hill, stretching down to the lakes and the groves, and forty stadia from the city; there was a mountainous height, that had many Pyramids standing upon it, the sepulchres of the kings, among which there are three remarkable, and two the wonders of the world.

This is the account of an eye-witness, an historian of the first credit, who mentions Memphis, and this state of it, so late as the reign of Nero; and therefore I shall conclude this argument with three observations, which, I am very sorry to say, could never have escaped a man of Dr Shaw's learning and penetration.1st, That by this description of Strabo, who was in it, it is plain that the city was not deserted in the time of the Ptolemies.

2dly, That no time, between the building of Alexandria and the time of the Ptolemies, could it be swallowed up by the river, or its situation unknown.

3dly, That great part of it having been built upon an eminence on the side of a hill, especially the large and magnificent edifices I have spoken of, it could not be situated, as he says, low in the bed of the river; for, upon the giving way of the Memphitic rampart, it would be swallowed up by it.

If it was swallowed up by the river, it was not Geeza; and this accident must have been since Strabo's time, which Dr Shaw will not aver; and it is by much too loose arguing to say, first, that the place was destroyed by the violent overflowing of the river, and then pretend its situation to be Geeza, where a river never came.

The descent of the hill to where the Pyramids were, and the number of Pyramids that were there around it, of which three are remarkable; the very sandy situation, and the quantity of loose flying hillocks that were there (dangerous in windy weather to travellers) are very strong pictures of the Saccara, the neighbourhood of Metrahenny and Mohannan, but they have not the smallest or most distant resemblance to any part in the neighbourhood of Geeza.

It will be asked, Where are all those temples, the Serapium, the Temple of Vulcan, the Circus, and Temple of Venus? Are they found near Metrahenny?

To this I answer, Are they found at Geeza? No, but had they been at Geeza, they would have still been visible, as they are at Thebes, Diospolis, and Syene, because they are surrounded with black earth not moveable by the wind. Vast quantities of these ruins, however, are in every street of Cairo: every wall, every Bey's stable, every cistern for horses to drink at, preserve part of the magnificent remains that have been brought from Memphis or Metrahenny.—The rest are covered with the moving sands of the Saccara; as the sphinxes and buildings that had been deserted were in Strabo's time for want of grass and roots, which always spread and keep the soil firm in populous inhabited places, the sands of the deserts are let loose upon them, and have covered them probably for ever.

A man's heart fails him in looking to the south and south-west of Metrahenny. He is lost in the immense expanse of desert, which he sees full of Pyramids before him. Struck with terror from the unusual scene of vastness opened all at once upon leaving the palm-trees, he becomes dispirited from the effects of sultry climates.

From habits of idleness contracted at Cairo, from the stories he has heard of the bad government and ferocity of the people, from want of language and want of plan, he shrinks from the attempting any discovery in the moving sands of the Saccara, embraces in safety and in quiet the reports of others, whom he thinks have been more inquisitive and more adventurous than himself.Thus, although he has created no new error of his own, he is accessary to the having corroborated and confirmed the ancient errors of others; and, though people travel in the same numbers as ever, physics and geography continue at a stand.

In the morning of the 14th of December, after having made our peace with Abou Cuffi, and received a multitude of apologies and vows of amendment and fidelity for the future, we were drinking coffee preparatory to our leaving Metrahenny, and beginning our voyage in earnest, when an Arab arrived from my friend the Howadat, with a letter, and a few dates, not amounting to a hundred.

The Arab was one of his people that had been sick, and wanted to go to Kenné in Upper Egypt. The Shekh expressed his desire that I would take him with me this trifle of about two hundred and fifty miles, that I would give him medicines, cure his disease, and maintain him all the way.

On these occasions there is nothing like ready compliance. He had offered to carry me the same journey with all my people and baggage without hire; he conducted me with safety and great politeness to the Saccara; I therefore answered instantly, "You shall be very welcome, upon my head be it." Upon this the miserable wretch, half naked, laid down a dirty clout containing about ten dates, and the Shekh's servant that had attended him returned in triumph.

I mention this trifling circumstance, to shew how essential to humane and civil intercourse presents are considered to be in the east; whether it be dates, or whether it be diamonds, they are so much a part of their manners, that, without them an inferior will never be at peace in his own mind, or think that he has a hold of his superior for his favour or protection.

- ↑ This has been thought to mean the Convent of Figs, but it only signifies the Two Convents.

- ↑ See Mr Irvine's Letters.

- ↑ Herod, lib. ii. p. 99.

- ↑ Herod, lib. ii. cap. 8.

- ↑ See the Chart of the Nile.

- ↑ Pococke, vol. I. cap. v. p. 39.

- ↑ Plin. lib, 5, cap. 9.

- ↑ Plin. lib. 36. cap. 12.

- ↑ Diod. Sic. p. 45. § 50.

- ↑ Shaw's Travels, p. 296. in the latitude quoted.

- ↑ Shaw's Travels, cap. 4. p. 298.

- ↑ Id. ibid. 299.

- ↑ Id ibid.

- ↑ Id. ibid.

- ↑ Ptol. Geograph. lib. iv. cap. 5.

- ↑ Herod. lib. ii. p. 141. Ibid. p. 168. Ibid. p. 105. Ibid. p. 103. Edit. Steph.

- ↑ Herod. lib. ii. § 97. p. 123

- ↑ Shaw's Travels, cap. 4.

- ↑ Strabo. lib. vii. .914.

- ↑ Id. ibid.

- ↑ Id. ibid.

- ↑ Strabo, ibid.

- ↑ Id. ibid.