Twentieth Century Impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and other Treaty Ports of China/Hongkong (Descriptive)

(Reproduced from the Directory and Chronicle for China, Japan, Straits, &c., by kind permission of the proprietors.)

HONGKONG.

By H. A. Cartwright.

RUGGED ridge of lofty granite hills, rising almost sheer out of the waters of the estuary of the Canton River, off the south-east coast of China, the island of Hongkong is well fashioned by Nature to serve as an outpost of the British Empire in the Far East. Extremely irregular in outline, it has an area of only 29 square miles, measuring 10½ miles in greatest length from north-east to south-west, and varying in breadth from 2 to 5 miles. The haunt of a few fishermen and freebooters less than seventy years ago, this tiny spot has become, in the hands of the British, a phenomenally prosperous entrepôt of trade at which ships hailing from all points of the compass discharge their cargoes and replenish their holds. The almost precipitous slopes of the hills, formerly as bare as the rocky escarpments on the opposite mainland, are covered from base to summit with luxuriant verdure, and a fine city of 300,000 inhabitants, who live amid all the advantages of Western civilisation, has sprung up along the northern shore and overflowed to the neighbouring peninsula. "It may be doubted," as Sir William des Voeux, a former Governor, wrote in a despatch to the Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1889, "whether the evidences of material and moral achievement, presented as it were in a focus, make anywhere a more forcible appeal to the eye and imagination, and whether any other spot on the earth is thus more likely to excite, or much more fully justifies, pride in the name of Englishman."

RUGGED ridge of lofty granite hills, rising almost sheer out of the waters of the estuary of the Canton River, off the south-east coast of China, the island of Hongkong is well fashioned by Nature to serve as an outpost of the British Empire in the Far East. Extremely irregular in outline, it has an area of only 29 square miles, measuring 10½ miles in greatest length from north-east to south-west, and varying in breadth from 2 to 5 miles. The haunt of a few fishermen and freebooters less than seventy years ago, this tiny spot has become, in the hands of the British, a phenomenally prosperous entrepôt of trade at which ships hailing from all points of the compass discharge their cargoes and replenish their holds. The almost precipitous slopes of the hills, formerly as bare as the rocky escarpments on the opposite mainland, are covered from base to summit with luxuriant verdure, and a fine city of 300,000 inhabitants, who live amid all the advantages of Western civilisation, has sprung up along the northern shore and overflowed to the neighbouring peninsula. "It may be doubted," as Sir William des Voeux, a former Governor, wrote in a despatch to the Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1889, "whether the evidences of material and moral achievement, presented as it were in a focus, make anywhere a more forcible appeal to the eye and imagination, and whether any other spot on the earth is thus more likely to excite, or much more fully justifies, pride in the name of Englishman."

Despite the assurances of friendship contained in this Treaty, the Chinese authorities consistently maintained an attitude of overbearing arrogance and ill-will towards the British, and a long series of insults culminated in the arrest of the Chinese crew of the Arrow, a small coasting vessel, sailing under the British flag, in October, 1856. Hostilities, long withheld, then broke out, and resulted in the capture of Canton in the following year by the British and French troops, who remained in occupation of the city for four years. In the meantime the importance, from a military point of view, of acquiring the Kowloon Peninsula—a small tongue of land, with an area of about 4 square miles, on the opposite side of Hongkong harbour—became evident, and on March 21, 1860, a perpetual lease was obtained from the Cantonese Viceroy, Lao Tsung Kwong. In the following October the peninsula was ceded to the British Crown under the Peking Convention, and, in 1898, at the suggestion of Sir Paul Chater, a 99 years' lease was obtained of the territory stretching behind it to a line drawn from Mirs Point, 140" 30' East, to the western extremity of Deep Bay, 113° 52' East, together with the islands of Lantau, Lamma, Cheung Chau, and others. The whole of this territory, embracing some 376 square miles, is now comprised in the Colony of Hongkong, which takes its name from the anchorage of Aberdeen, on the south of the island, known to the native fishermen as Heung-kong, signifying "good harbour." The European mariners who were in the habit of putting in here to obtain supplies of water from the stream which falls into the sea at Aberdeen village mistook the name of the anchorage for that of the whole island, and marked their charts accordingly. The name first appeared as one word in the Royal Charter published in the Government Gazette in 1843, and by the same instrument the city of Victoria received its present appellation. The word Kowloon is derived from the Chinese words Kau-lung, signifying "nine dragons," in reference to the nine hills which form the background of the peninsula.

Prior to the arrival of the British, the population of the island probably never exceeded 2,000. The ostensible occupation of the inhabitants was fishing, but the term Ladrones (robbers), by which this and the adjacent islands were known to the Portuguese, shows that they practised something else besides "the gentle art"; indeed, piracies were a source of infinite trouble to the British settlers for many years. In October, 1841, the population of Hongkong, including both the troops and residents of all nationalities, was estimated at 15,000, or thrice as many as six months previously. By 1848 the total had increased to 21,514. A rebellion which broke out in the provinces adjacent to Canton in the early fifties sent a flood of emigrants to Hongkong, and the population rose to nearly 40,000 in 1853, and to 75,500 in 1858. Between 1860 and 1861, when the peninsula of Kowloon was added to the Colony, the numbers increased from 94,917 people to 119,321, but from that date onward to 1872 very little progress was made. Four years later, however, a census revealed 139,144 souls, due in part to the influx of some hundreds of Portuguese families from Macao after the destructive typhoon of 1874. In 1881 there were in the Colony 150,000 Chinese, and 9,622 British, Portuguese, and other non-Chinese inhabitants. To-day the population of the Colony—exclusive of the New Territory, which is estimated to contain about 85,000 Chinese—may be set down as 330,000. This figure includes some 9,000 soldiers and sailors, and a floating population of nearly 50,000 Chinese men, women, and children who, from the cradle to the grave, know no home other than their junks, or sampans, afford. The non-Chinese civil community numbers about 10,000, and includes Europeans, Eurasians, Indians, Malays, and Africans.In the early days of the Colony the ravages of disease were so disastrous that in 1844 the advisability of abandoning the island was seriously discussed. Mr. Montgomery Martin, Her Majesty's Treasurer, drew up a long report in which he expressed the belief that the place would never be habitable for Europeans, and, in support of this statement, he cited the case of the 98th Regiment, which lost 257 men by death in twenty-one months, and of the Royal Artillery, whose strength fell in two years from 135 to 84, from the same cause. General D'Aguilar, the Commander of the Forces, also expressed the opinion that to retain Hongkong would involve the loss of a whole regiment every three years. These gloomy views, however, were not shared by Sir John Davis, the Governor, who stoutly maintained that time alone was required for the development of the Colony and for the correction of some of the evils that hindered its early progress. Sir John lived to see his prediction amply verified. Malarial fever, which proved such a scourge in those days—owing, it seems, to the noxious exhalations from the disintegrated granite disturbed in the course of building operations—has received so much attention from the Medical and Sanitary Departments that its toll of human life is decreasing year by year. The chief causes of mortality now are plague, dysentery, diarrhoea, malarial fever, and small-pox. The death-rate for 1907 was 22·12 per thousand of the inhabitants, but for the non-Chinese community it was as low as 15·46, which compares not unfavourably with many large towns in the United Kingdom. The birth-rate, however, is small. Among the non-Chinese it was equivalent to 15·95 per mille, but for the whole community it was only 4·31 per mille. This latter figure would, no doubt, be somewhat higher but for the Chinese custom of not registering a birth unless the child survives for a month, and often, in the case of a female child, of not registering it at all.

In the jeremiad of Mr. Montgomery Martin, referred to above, the opinion was expressed that it would be a delusion to hope that Hongkong would ever become a commercial emporium like Singapore. Again the progress of events has shown Mr. Martin to be a false prophet, for Hongkong is now the pivot upon which the trade of South China turns. Although, in accordance with the understanding given to the Chinese by Sir H. Pottinger when negotiating the Nanking Treaty, the port is free, and, therefore, no official record of the exports and imports is compiled, the annual value of the trade is estimated at no less than fifty millions sterling. A comparatively small but increasing proportion of this trade consists of local manufactures. In respect of tonnage, Hongkong is the largest shipping port in the world. In 1907 the total tonnage entered and cleared amounted to 36,000,000 tons. To this total ocean-going steamers and war vessels exceeding 60 tons contributed about 19,500,000 tons, of which more than one-half—to be exact, 11,846,533 tons—was British.

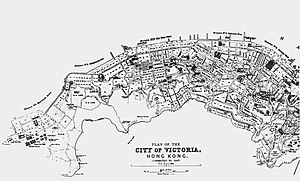

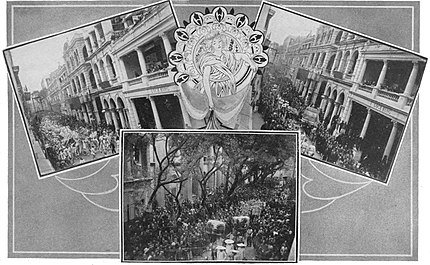

The harbour—one of the most extensive and picturesque in the world—consists of the sheltered anchorage lying between the northern shore of the island and the opposite mainland. It varies in width from a third of a mile at the Ly-ee-mūn Channel, on the east, to 3 miles at the widest point, and has an area of 10 square miles. On either side the hills and mountains stand guard like silent sentinels, and combine to produce a spectacle of impressive grandeur. The intervening stretch of water is at all times thickly studded with vessels of every conceivable size and shape—from the little junks, or sampans, of the natives to the warships of the China squadron and the majestic liners of 27,000 tons burden belonging to the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. A busy, clamorous life prevails on every side. Steam launches dart hither and thither, innumerable sampans wriggle their tortuous courses backward and forward between the ships and the shore, junks pick their way up and down the fairways under lateen sails, and ocean-going steamers move in stately fashion to and from their moorings. Viewed from the harbour, Hongkong presents a very picturesque appearance, not unlike that of the north coast of Devon, or the west coast of Scotland. At night time the scene resembles a city en fête. The riding lights of the shipping sparkling like gems on the bosom of the deep, the bright illuminations of the water-front, and the countless lamps that bespangle the hillsides and stretch along the terraces as though in festoons, furnish a sight that fascinates the eye and leaves an enduring impression of delight upon the mind.Nestling at the foot of the hills, and stretching from east to west for nearly five miles along the northern coast of the island, is the city of Victoria. A thriving hive of industry, built on a narrow riband of land, much of which has been won from the sea, it is a wonderful monument to the enterprise, energy, and success of the British as colonisers. The streets are well laid out and well kept, and the buildings which abut upon them are remarkable for their massive and imposing design. The Praya, which borrows its name from the embankment in the neighbouring colony of Macao, is some 50 feet wide, and extends along the entire sea-front, except for a short distance where its continuity is broken by the buildings of the War Office and the Admiralty. The original Praya wall was commenced during the governorship of Sir Hercules Robinson (1859–65), when extensive reclamations of land were made from the sea. The work, however, was demolished by a terrific typhoon in August of 1867, and was again seriously damaged by a similar visitation in 1874. Undismayed, however, the inhabitants repaired the breaches, and, in 1890, at the initiative of Sir Paul Chater, another considerable tract of land was added to the European business area. It is now proposed to carry the Praya a quarter of a mile further out to sea from the Naval Yard to Causeway Bay, a mile and a quarter to the east.

Almost parallel with the Praya runs Des Voeux Road, and behind this is Queen's Road, flanked with fine shops, and extending from the water's edge at Kennedy Town, on the west, to within a short distance of Happy Valley, on the east—in all some four miles. Originally Queen's Road was just above high-water mark, and gave its name to the rising township, which was known as Queen's Town before it became the city of Victoria in 1843. These three roads—the Praya (or Connaught Road), Des Voeux Road, and Queen's Road—form the main arteries of traffic, and are intersected at right angles by a number of short streets. Space is too precious to allow of any of these being very wide, but this is not a matter of much moment in view of the almost entire absence of horsed conveyances. Vehicular traffic is confined chiefly to handcarts, rickshaws, chairs suspended from poles borne on the shoulders of coolies, there being but a few pair-pony gharries, and a Victoria or two used by Chinese.

The European business quarter lies in the centre of the town, between Pottinger Street and the Naval Yard. Within this small area of less than 50 acres are grouped handsome blocks of offices ranging from four to six storeys in height, that would not suffer by comparison with those of many cities in the United Kingdom. They stand upon pile foundations, and are built to meet local conditions. The verandahs, by which all of them are surrounded, render any pure style of architecture impossible, but, generally speaking, it may be said that the prevailing tone, so far as it can be identified with any particular period, is that of the Italian Renaissance. This applies to Queen's Buildings, a block measuring 180 feet square, with four storeys, surmounted by towers 150 feet in height; Prince's Buildings, a similar block; George's, King's, Alexandra, and York Buildings, Hotel Mansions, the Hongkong Club, and the premises of the Eastern Extension Telegraph Company, and of Messrs. Butterfield & Swire. Not far removed from these, and occupying a corner site abutting upon Queen's Road and Des Voeux Road, is the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, a handsome granite structure in classical Roman Corinthian style, surmounted by a large dome. Next to this is the City Hall, a striking building in Romanesque style, carried out in stucco work, containing a theatre, library, museum, and several halls—approached by a fine stone staircase—in which dances and other gatherings are held. In front of the main entrance stands a large fountain, consisting of four allegorical figures supporting a bowl, from the centre of which rises another figure holding a cornucopia. This was the gift, in 1864, of Mr. Dent, a former merchant of the Colony. Opposite to the entrance of the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank in Des Voeux Road is a tastefully laid-out garden, held in reserve by the bank. In a recess at the entrance to this enclosure is a life-size bronze statue of Sir Thomas Jackson, a former manager of the institution, who received the honour of a baronetcy in recognition of his financial services to the Colony. Upon a site adjacent to this open space, where Chater Street and Wardley Street cross one another, a bronze jubilee statue has been erected of H.M. the late Queen Victoria, enthroned under a canopy of Portland stone. Near by stand a bronze statue of H.M. the King, presented by Sir Paul Chater, C.M.G., and another of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, the gift of Mr. James Jardine Bell-Irving, both of which were unveiled by H.R.H. the Duke of Connaught when, as Inspector-General of the Forces, he visited the Colony on February 6, 1907. A statue of H.M. Queen Alexandra, subscribed for by the community as a memorial of the coronation of Their Majesties in 1902, and one of H.R.H. the Princess of Wales, presented by Mr. H. N. Mody, are also to be placed in the same square at an early date. Between this square and the adjacent cricket-ground the new Law Courts are in course of construction. The principal elevation, facing west, will represent the classic Ionic order, and will be crowned by a Doric dome terminating at a height of 130 feet from the ground. The front of the building will be split into fifteen bays with Ionic columns, the bases of which will be 6 feet 3 inches square. Over the centre of the front will be a pediment containing a semi-circular opening, above which the royal arms will be supported by figures of Mercy and Truth. From the main tier will rise a granite statue of Justice, 9 feet in height. Another notable addition to the architectural features of the city is being made by the erection of a splendid set of Government Offices, four storeys in height, in the centre of the European business area. The building will occupy a prominent corner site, more than half an acre in extent, with frontages to Connaught Road, Pedder Street, and Des Voeux Road. The principal elevation, facing Pedder Street, will be a free treatment of the Renaissance style carried out in local granite and Amoy bricks. The line of the parapet, 78 feet from the ground, will be broken by ornamental gables, and each of the eastern angles will be surmounted by a graceful turret. In the centre of the northern front, overlooking the harbour, a bold square clock-tower will rise to a height of over 200 feet. At the other end of Pedder Street may be seen the unpretentious and ill-arranged structure, containing the Post Office, Supreme Court, and some of the other Government Offices, which these two new buildings are intended to supersede. In line with it, at the entrance to Queen's Road, stands an ugly clock-tower, erected by public subscription in 1862, at the suggestion of Mr. J. Dent, whose original design had to be stripped of its original decorative features, owing to the waning enthusiasm of the community.Chinatown stretches westward from Pottinger Street. It consists of a labyrinth of streets, many of them very narrow, closely packed at all hours of the day with a jostling mass of humanity. Here are to be seen reproduced all the familiar phases of Chinese life—squalid-looking shops packed with a strange medley of things; artisans patiently and deftly plying their trades as braziers, tinkers, or carpenters; itinerant vendors of food-stuffs and other commodities, stooping under heavy loads suspended from bamboo poles borne across the shoulders; and urchins at play in the less-frequented courts and alleys. It is in this densely overcrowded area that plague and small-pox find a stronghold, but within the last decade the Sanitary Board has done much to combat the spread of these diseases, by making house-to-house visitations, and insisting, as far as possible, upon the provision of proper air-space, ventilation, and sanitation.

In this neighbourhood are situated several hotels where the mysteries of Chinese "chow" await the intrepid; two theatres in which Chinese conceptions of the drama find weird expression; the Tung Wah Hospital, a purely Chinese institution maintained by voluntary contributions; the Government Civil Hospital, a large and well-designed building affording extensive accommodation; and the Nethersole Hospital. This last is affiliated with the Alice Memorial Hospital at the corner of Hollywood Road and Aberdeen Street, a useful and philanthropic institution, which serves also as the headquarters of the Hongkong College of Medicine for Chinese. A little higher up Aberdeen Street, with its chief frontage in Staunton Street, is Queen's College, the chief educational institution of the Colony.At the opposite end of the town are the Military Hospital, a fine range of buildings along Bowen Road at an elevation of 400 feet above sea-level; and the Royal Naval Hospital, occupying a small eminence at the eastern extremity of Queen's Road.

On the other side of the Gap is Happy Valley, the great rallying point of those who take an interest in out-door sports. A level stretch of green sward enclosed by lofty fir-clad hills, it bears a remarkable resemblance to Grasmere, in the English lake district. Around it runs a circular racecourse, seven furlongs in circumference, and, within this, ample provision has been made for cricket, football, and golf. On the occasion of the annual races, which are held under the auspices of the Hongkong Jockey Club in February, the whole Colony makes holiday for three days, and the course is crowded. The excitement and enthusiasm inseparable from an English meeting are, however, entirely absent here, the proceedings being conducted with a funereal decorum. This may be traceable to the close proximity of the trimly-kept cemeteries—Mahomedan, Roman Catholic, Protestant, Parsee, and Hindu—which cover the side of the hill at the rear of the grand-stand as though designed, like the death's-head at the Roman feast, to serve as a reminder of the transient nature of earthly pleasures.

Beyond Happy Valley lies the Chinese fishing village of Shaukiwan, in a sheltered bay near the Ly-ee-mùn Pass. This can be reached by the electric tramway which runs from Belcher's Bay on the west, through the city of Victoria to this point, in all, a distance of nine and a half miles. On the way several large factories are passed, chief among them being the important sugar refilling works on the left, and the large cotton-spinning works on the right, of Messrs. Jardine, Matheson & Co., at Causeway Bay, and the huge sugar refinery and shipbuilding yard of Messrs. Butterfield & Swire at Quarry Bay.

A winding path between the hills leads to Stanley by way of Tytam Tuk, a little village nestling among trees at the head of Tytam Bay, the most extensive inlet on the southern coast. Stanley was formerly a military station, but it was abandoned by the troops for reasons which are explained only too eloquently by the graves that fill the cemetery on the point. Five or six miles west of Stanley is Aberdeen, which possesses a well-sheltered little harbour much frequented by fishing craft, also two large docks, a paper mill, and the Colony's only brick, pipe, and tile manufactory. From Aberdeen there is a choice of two carriage roads to Victoria—one leading to Bonham Road through Pokfolum, formerly a favourite place of resort for European residents in hot weather; and the other, constituting a portion of the new Diamond Jubilee Road, passing through most charming scenery to the Tramway Terminus at West Point.From Queen's Road a number of steep roads and paths ascend the lower slopes of the hills, which above the centre of the city are dotted with attractive residences, thickly at first, and then at wider intervals as the Peak is approached. These residences—of solid masonry embowered in green—are approached by well made zig-zig paths shaded with trees. Conspicuous by reason of its beauty and its isolation is Marble Hall, the home of Sir Paul Chater, which contains a collection of china. Ascending by way of Garden Road, which is the beginning of a delightful though rather exacting walk to the summit, one passes, on the right, the Anglican Cathedral of St. John, rising out of a wealth of tropical foliage. Though of no particular style, but with a tendency to Gothic, this edifice is not lacking in beauty. The square tower, surmounted by pinnacles, has a grace of its own and is a feature of the landscape from many points of view. Near by stands an unpretentious group of Government Offices, whose plainness is relieved by the surrounding vegetation. A little higher up on the same side is Government House, a commodious and substantially built residence, dating from the year 1857. Above this and lying on either side of Albany Road are the Public Gardens, tastefully laid out in walks and terraces, and containing a profusion of rare palms, trees, and shrubs, and a constant succession of bright flowers. The collection of palms is especially noteworthy, for it embraces specimens from all parts of the world. A handsome fountain adorns the second terrace, and looking down upon this is a large bronze statue of Sir Arthur Kennedy, who was a popular Governor of the Colony from 1872 to 1876. From this coign of vantage a view is obtained of the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Joseph, a cruciform building with a central tower at the intersection and a detached Gothic campanile tower. The sacred edifice occupies a delightful site in Glenealy, one of the prettiest ravines in the Colony, which is shortly to be desecrated by a second tramway line to the Peak. On the left side of Garden Road, after passing Murray Barracks and the terminus of the little funicular tramway which gives easy access to Victoria Gap, entrance is gained to Kennedy Road, along which lie the Union Church, a pleasing little edifice in the Italian style, and the handsome premises of the German Club. This road, which winds round the hill and eventually leads down to the Gap, forms a very pleasant promenade. Throughout its entire length of about a mile and a half charming glimpses of the harbour are obtainable through the interlacing trees which form a canopy overhead, while here and there little rills come splashing down over rocks and hide themselves in the tangled vegetation below. On a similar level to this road, but running in an opposite direction, is Caine Road, and, above that and in a line with MacDonnell Road, is Robinson Road. Both roads eventually merge into Bonham Road, which eventually loses itself in Pokfolum Road, leading to the village of Aberdeen, on the south side of the island. Caine Road is largely built upon, but from Bonham Road onwards the road becomes more rural in character and commands fine sea views.

Parallel with Kennedy Road and at a height of 400 feet above sea-level, Bowen Road traverses the face of the hills from Happy Valley to a point above the centre of the town some four miles further to the west. This aqueduct and viaduct—for such it is—was constructed for the purpose of conveying water from the Tytam reservoir. In many parts it is carried over the ravines and rocks by ornamental stone bridges, one of which, above Wanchai, has twenty-three arches. The road commands magnificent views of the eastern district, and is a favourite resort of pedestrians.

Around Victoria Gap a little hill settlement has been formed, possessing its own club and its own church, as well as several hospitals. The reason for the popularity of this district is not far to seek. In summer time, when the city below is wrapped in a haze of clammy heat, the atmosphere at this altitude is several degrees cooler and less humid. Throughout the winter a succession of crisp, clear days is experienced, and it is only during the spring, when everything is enveloped in a thick veil of mist, that the lower levels seem more desirable places of residence. Numerous paths branch off from Victoria Gap—some to the neighbouring hills and others to Pokfolum and Aberdeen. A road to the westward ascends the Peak, which rises abruptly behind the city of Victoria to a height of nearly 2,000 feet. From the summit of this eminence a magnificent panorama lies unfolded to the view. Across the harbour with its busy movement, the brown, arid-looking hills of the mainland rear their crests against the sky, while to the south, east, and west the Canton Delta, a wide expanse of blue water, set with opalescent-looking islands, stretches as far as the eye can reach. At the close of day when the shades steal up from the east and the sinking sun paints the western horizon with rich tints of orange, yellow, and primrose that invest even the bare hills with a golden glow, the spectacle is one of indescribable charm.

Communication between Victoria and the Kowloon Peninsula is maintained by a number of ferry launches, the most important being the Star Ferry Company's boats, which cross from the centre of the city direct to Tsim-tsa-tsui Point. The other launches are used by Chinese only, and run to Hunghom and Kowloon City, on the eastern side of the peninsula, and Yaumati and Sam Shui Po on the western side. At the present time Kowloon is in its youth, but it is growing vigorously, and gives fair promise for the future, when the Kowloon-Canton Railway shall have linked it up with Peking and the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Practically all the wharves in the Colony are on the peninsula—a fact which accounts for the clean appearance of the water front at Victoria. At Sam Shui Po the Hongkong and Whampoa Dock Company have constructed the Cosmopolitan Docks. The Hongkong Wharf and Godown Company own a large slice of the foreshore on the western side of the peninsula, and upon this they have built new wharves to take the place of those destroyed in the typhoon of September 18, 1906. Messrs. Butterfield & Swire, also, have erected new steel wharves on the reclaimed land at the very point of the peninsula, and at the time of writing are adding huge godowns, which will be in close proximity to the terminus of the line from Kowloon to Canton that is now under construction. The necessary land for the railway station, shunting yards, workshops, &c., in connection with this project, is being obtained by extensive reclamations on the eastern side of the peninsula, this method being less costly than purchasing land; and it requires no great prophetic instinct to predict that in time the whole of Hunghom Bay will be reclaimed.Close to the Ferry Wharf, and occupying an eminence that commands a good view of the harbour, is the Water Police Station, and from the flagstaff on Signal Hill to the eastward weather signals are exhibited both day and night, the time-ball is operated, and incoming vessels are announced. The Post Office, in close proximity to the wharf, is a small building, but is large enough for the present needs of the locality. Small residences, most of which are semi-detached, are scattered about close to the water, and behind these are terraces of small dwellings—each containing from four to six airy rooms—which are mainly occupied by those to whom the high rentals demanded in the island of Hongkong are prohibitive. All the roads on the peninsula are wide and lined with trees, and two in particular—Robinson Road and Gascoigne Road—are noticeable by reason of their width. In the former is situated the Anglican Church of St. Andrew—an excellent example of modern work in Early English Gothic style—presented by Sir Paul Chafer; and close to this is the Kowloon British School erected in 1901 at the expense of Mr. Ho Tung. It may here be mentioned, in passing, that there is a Roman Catholic Church in Des Voeux Road, the gift of Mr. S. A. Gomes. Gascoigne Road, which is 100 feet wide, runs right across the peninsula from Hunghom to Yaumati, and skirts the King's Park, a large enclosure reserved for recreation, and the United Services Recreation Ground.

The Hongkong Observatory, a large but unpretentious building, the equipment of which was adversely criticised after the 1906 typhoon, is situated on Mount Elgin, in the centre of the peninsula. Skirting the peninsula to the east, and passing the military barracks, Hunghom, a small village in which the dock hands live, is reached. Sampans and small junks lie crowded together at the head of the bay, the shores of which are lined with engineering works, the most important being those of the Hongkong and Whampoa Dock Company. There is also an electric light and power station here.

Beyond the small villages of Hok-ün and Tukwawan, Matauchung and Hgatsinlong, is Kowloon City, once a thriving town but now simply a collection of dilapidated dwellings. Kowloon City, which is surrounded by a high granite wall, was seized by the British in May, 1899, although the agreement under which the New Territory was leased to the British specially stipulated that it was to remain in the hands of the Chinese. The circumstances which led to the taking of the city are interesting enough to bear repetition. Just prior to the date for taking over the New Territory (April 17, 1899) the British parties engaged in making the preliminary arrangements were attacked by bands of rebels, and military operations were found necessary. An engagement was fought at Sheung Tsun on April 18th, and the rebel force, estimated at 2,500 men, was completely routed, but, even after this, intermittent outbreaks occurred. As it was established beyond doubt that the Chinese authorities were by no means innocent in the matter of this disturbance, the Home Government, to mark their sense of the duplicity of the Chinese, directed the military authorities to occupy Kowloon City and Samchun. This instruction was carried out in May. The Hongkong Volunteers cooperated in the attack on Kowloon City, but it proved to be a bloodless campaign, no resistance being offered to the British force. Since then Kowloon City has remained in the hands of the British, but Samchun, an important town on the border between China and the New Territory, was handed back to the Chinese in November, 1899, and has, unfortunately, become a convenient asylum for Chinese criminals who are "wanted" by the Hongkong authorities.

On the western side of the peninsula lies the important village of Yaumati, which is very thickly populated by Chinese, and contains the gas works from which the gas is obtained for lighting the peninsula. After passing through this village the open country is met. A splendid road winds along the high range of hills which divides the peninsula from the mainland, rising gradually higher until a break in the hills is reached, when the road turns sharply to the right and descends into the Shatin Valley. The road passes the extensive waterworks which have been completed in recent years, and winds to the east at Kauprkang, near which stands the largest reservoir in the Colony. The country to the north of the hills is extremely fertile, and large areas are taken up in the cultivation of paddy. The broad expanse of the valley is dotted here and there with small farmhouses and fields of paddy, while at the base of the hills, and ascending for some little distance up the slopes, are tiny rice fields arranged in terraces one above the other. Primitive ploughs, drawn by carribous, are used in these fields, and irrigation is carried out by hand. Chinese women work in the fields, which are usually covered with water several inches deep. Pineapples, peanuts, and many other like products are grown in this valley, but not to any large extent. Hilly country, intercepted by valleys, continues as far as Taipohu—the headquarters of the British administration—on the shores of Tolo Channel, in Mirs Bay, after which a wide expanse of level country stretches to the border of the British sphere of influence and beyond.Although the industries of the territory are few, there is promise of development in the future. Iron ore and silver have been found, but little beyond prospecting has been done up to the present, owing, no doubt, to the absence of coalfields in the vicinity. The country is being opened up by means of roads, peace and order are being preserved by the establishment of police stations, and a system of administration is being organised by means of village committees.