A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Modulation

MODULATION is the process of passing out of one key into another.

In modern harmonic music, especially in its instrumental branches, it is essential that the harmonies should be grouped according to their keys; that is, that they should be connected together for periods of appreciable length by a common relation to a definite tonic or keynote. If harmonies belonging essentially to one key are irregularly mixed up with harmonies which are equally characteristic of another, an impression of obscurity arises; but when a chord which evidently belongs to a foreign key follows naturally upon a series which was consistently characteristic of another, and is itself followed consistently by harmonies belonging to a key to which it can be referred, modulation has taken place, and a new tonic has supplanted the former one as the centre of a new circle of harmonies.

The various forms of process by which a new key is gained are generally distributed into three classes Diatonic, Chromatic and Enharmonic. The first two are occasionally applied to the ends of modulation as well as to the means. That is to say, Diatonic would be defined as modulation, to relative keys, and Chromatic to others than, relative. This appears to strain unnecessarily the meaning of the terms, since Diatonic and Chromatic apply properly to the contents of established keys, and not to the relations of different shifting ones, except by implication.

Moreover, if a classification is to be consistent, the principles upon which it is founded must be uniformly applied. Hence if a class is distinguished as Enharmonic in relation to the means (as it must be), other classes cannot safely be classed as Diatonic and Chromatic in relation to ends, without liability to confusion. And lastly, the term Modulation itself clearly implies the process and not the result. Therefore in this place the classification will be taken to apply to the means and not to the end, to the process by which the modulation is accomplished and not the keys which are thereby arrived at.

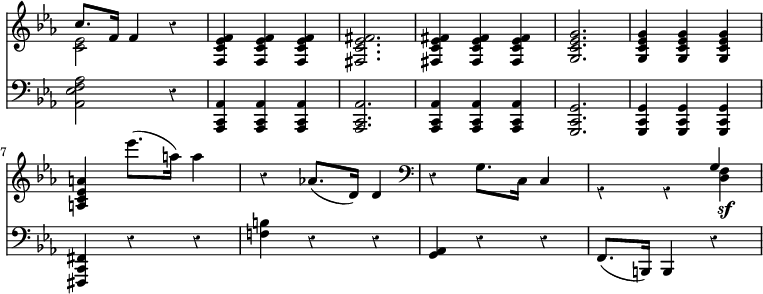

The Diatonic forms, then, are such as are effected by means of notes or chords which are exclusively diatonic in the keys concerned. Thus in the following example (Bach, Well-tempered Clavier, Bk. 2, no. 12):—

the chord at * indicates that F has ceased to be the tonic, as it is not referable to the group of harmonies characteristic of that key. However, it is not possible to tell from that chord alone to what key it is to be referred, as it is equally a diatonic harmony in either B♭, E♭, or A♭; but as the chords which follow all belong consistently to A♭, that note is obviously the tonic of the new key, and as the series is Diatonic throughout it belongs to the Diatonic class of modulations.

The Chromatic is a most ill-defined class of modulations; and it is hardly to be hoped that people will ever be sufficiently careful in small matters to use the term with anything approaching to clear and strict uniformity of meaning. Some use it to denote any modulation in the course of which there appear to be a number of accidentals—which is perhaps natural but obviously superficial. Others again apply the term to modulations from one main point to another through several subordinate transitions which touch remote keys. The objection to this definition is that each step in the subordinate transitions is a modulation in itself, and as the classification is to refer to the means, it is not consistent to apply the term to the end in this case, even though subordinate. There are further objections based upon the strict meaning of the word Chromatic itself, which must be omitted for lack of space. This reduces the limits of chromatic modulation to such as is effected through notes or chords which are chromatic in relation to the keys in question. Genuine examples of this kind are not so common as might be supposed; the following example (Beethoven, op. 31, no. 3), where passage is made from E♭ to C is consistent enough for illustration:—

The third class, called Enharmonic, which tenda to be more and more conspicuous in modern music, is such as turns mainly upon the translation of intervals which, according to the fixed distribution of notes in the modern system, are identical, into terms which represent different harmonic relations. Thus the minor seventh, G-F, appears to be the same interval as the augmented sixth G-E♯; but the former belongs to the key of C, and the latter either to B or F♯, according to the context. Again, the chord which is known as the diminished seventh is frequently quoted as affording such great opportunities for modulation, and this it does chiefly enharmonically; for the notes of which it is composed being at equal distances from each other can severally be taken as third, fifth, seventh or ninth of the root of the chord, and the chord can be approached as if belonging to any one of these roots, and quitted as if derived from any other. The passage quoted from the Leonore Overture in the article Change (vol. i. p. 333a) may be taken as an example of an enharmonic modulation which turns on this particular chord.

Enharmonic treatment really implies a difference between the intervals represented, and this is actually perceived by the mind in many cases. In some especially marked instances it is probable that most people with a tolerable musical gift will feel the difference with no more help than a mere indication of the relations of the intervals. Thus in the succeeding example the true major sixth represented by the A♭-F in (a) would have the ratio 5:3 ( = 125:75), whereas the diminished seventh represented by G♯-F♮ in (b) would have the ratio 128:75; the former is a consonance and the latter, theoretically, a rough dissonance, and though they are both represented by the same notes in our system, the impression produced by them is to a certain extent proportionate to their theoretical rather than to their actual constitution.

Hence it appears to follow that in enharmonic modulation we attempt to get at least some of the effects of intervals smaller than semitones; but the indiscriminate and ill-considered use of the device will certainly tend to deaden the musical sense, which helps us to distinguish the true relations of harmonies through their external apparent uniformity.

A considerable portion of the actual processes of modulation is effected by means of notes which are used as pivots. A note or notes which are common to a chord in the original key and to a chord in the key to which the modulation is made, are taken advantage of to strengthen the connection of the harmonies while the modulation proceeds; as in the following modulation from G♯ major to B major in Schubert's Fantasie-Sonata Op. 78.

This device is found particularly in transitory modulation, and affords peculiar opportunities for subtle transitions. Examples also occur where the pivot notes are treated enharmonically, as in the following example from the chorus 'Sein Odem ist schwach' in Graun's 'Tod Jesu':

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f << \new Staff { \time 4/4 \key ees \major << \new Voice { \autoBeamOff \stemUp \relative b' { b8[ c] c g aes! aes aes aes | gis4 gis8 gis a4 } }

\new Voice { \stemDown \relative g' { \autoBeamOff g4 g8 d ees ees f f | b,4 b8 b cis4_\markup { \halign #-1 etc. } } } >> }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key ees \major << \new Voice { \autoBeamOff \stemUp \relative d' { d8[ ees] ees b c c d d | d4 d8 d cis4 } }

\new Voice { \autoBeamOff \stemDown g4 g g8 g f f | e4 e a, } >> } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/g/3/g3hq7lu5ff52moa90pli1okauq3377l/g3hq7lu5.png)

These pivot-notes are however by no means indispensable. Modulations are really governed by the same laws which apply to any succession of harmonies whatsoever, and the possibilities of modulatory device are in the end chiefly dependent upon intelligible order in the progression of the parts. It is obvious that a large proportion of chords which can succeed each other naturally—that is, without any of the parts having melodic intervals which it is next to impossible to follow—will have a note or notes in common; and such notes are as useful to connect two chords in the same key as they are to keep together a series which constitute a modulation. But it has never been held indispensable that successive chords should be so connected, though in earlier stages of harmonic music it may have been found helpful; and in the same way, while there were any doubts as to the means and order of modulation, pivot-notes may have been useful as leading strings, but when a broader and freer conception of the nature of the modern system has been arrived at, it will be found that though pivot-notes may be valuable for particular purposes, the range of modulatory device is not limited to such successions as can contain them, but only to such as do not contain inconceivable progression of parts. As an instance we may take the progression from the dominant seventh of any key, to the tonic chord of the key which is represented by the flat submediant of the original key: as from the chord of the seventh on G to the common chord of A♭; of which we have an excellent example near the beginning of the Leonore Overture No. 3. Another remarkable instance to the point occurs in the trio of the third movement of a quartet of Mozart's in B♭, as follows:—

Other examples of modulation without pivot-notes may be noticed at the beginning of Beethoven's Egmont Overture, and of his Sonata in E minor, op. 90 (bars 2 and 3), and of Wagner's Gotterdammerung (bars 9 and 10). An impression appears to have been prevalent with some theorists that modulation ought to proceed through a chord which was common to both the keys between which the modulation takes place. The principle is logical and easy of application, and it is true that a great number of modulations are explicable on that basis; but inasmuch as there are a great number of examples which are not, even with much latitude of explanation, it will be best not to enter into a discussion of so complicated a point in this place. It will be enough to point out that the two principles of pivot-notes and of ambiguous pivot-chords between them cover so much ground that it is not easy to find progressions in which either one or the other does not occur and even though in a very great majority of instances one or the other may really form the bond of connection in modulatory passages, the frequency of their occurrence is not a proof of their being indispensable. The following passage from the first act of Wagner's Meistersinger is an example of a modulation in which they are both absent:—

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f << \new Staff { \time 2/4 << \new Voice { \stemUp \relative a'' { a16 g f a ~ a g e g | f e d bes' fis e dis b' g fis e g } }

\new Voice { \stemDown \relative f' { s8 \acciaccatura { f16[ g] } <a c,>8 s \acciaccatura { g16[ f] } <e c>8 | s \acciaccatura { d16[ e] } <f bes,>8 s \acciaccatura { fis16[ e] } <dis fis,>8 | s \acciaccatura { e16[ fis] } <g b>8 } } >> }

\new Staff { \clef bass f8 s c s d s b,! s e s } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/h/nhvyo2yvqjlkomss6pc3ggheanacmp7/nhvyo2yv.png)

The real point of difficulty in modulation is not the manner in which the harmonies belonging to different keys can be made to succeed one another, but the establishment of the new key, especially in cases where it is to be permanent. This is effected in various ways. Frequently some undoubted form of the dominant harmony of the new key is made use of to confirm the impression of the tonality, and modulation is often made through some phase of that chord to make its direction clear, since no progression has such definite tonal force as that from dominant to tonic. Mozart again, when he felt it necessary to define the new key very clearly, as representing a definite essential feature in the form of a movement, often goes at first beyond his point, and appears to take it from the rear. For instance, if his first section is in C, and he wishes to cast the second section and produce what is called his second subject in the dominant key G, instead of going straight to G and staying there, he passes rapidly by it to its dominant key D, and having settled well down on the tonic harmony of that key, uses it at last as a dominant point of vantage from which to take G in form. The first movement of the Quartet in C, from bar 22 to 34 of the Allegro, will serve as an illustration. Another mode is that of using a series of transitory modulations between one permanent key and another. This serves chiefly to obliterate the sense of the old key, and to make the mind open to the impression of the new one directly its permanency becomes apparent. The plan of resting on dominant harmony for a long while before passing definitely to the subjects or figures which are meant to characterise the new key is an obvious means of enforcing it; of which the return to the first subject in the first movement of Beethoven's Waldstein Sonata is a strong example. In fact insistance on any characteristic harmony or on any definite group of harmonies which clearly represent a key is a sure means of indicating the object of a modulation, even between keys which are remote from one another.

In transitory modulations it is less imperative to mark the new key strongly, since subordinate keys are rightly kept in the background, and though they may be used so as to produce a powerful effect, yet if they are too much insisted upon, the balance between the more essential and the unessential keys may be upset. But even in transitory modulations, in instrumental music especially, it is decidedly important that each group which represents a key, however short, should be distinct in itself. In recitative, obscurity of tonality is not so objectionable, as appears both in Bach and Handel; and the modern form of melodious recitative, which often takes the form of sustained melody of an emotional cast, is similarly often associated with subtle and closely woven modulations, especially when allied with words. Of recitative forms which show analogous freedom of modulation in purely instrumental works, there are examples both by Bach and Beethoven, as in an Adagio in a Toccata in D minor and the Fantasia Cromatica by the former, and in the Introduction to the last movement of the A♭ Sonata (opus, 110) of the latter.

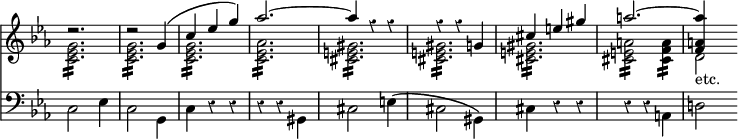

When transitory modulations succeed one another somewhat rapidly they may well be difficult to follow if they are not systematised into some sort of appreciable order. This is frequently effected by making them progress by regular steps. In Mozart and Haydn especially we meet with the simplest forms of succession, which generally amount to some such order as the roots of the chord falling fifths or rising fourths, or rising fourths and falling thirds successively. The following example from Mozart's C major Quartet is clearly to the point.

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical << \new Staff { \time 2/4 \key c \major << \new Voice { \relative d''' { \stemUp <d gis,>4 <cis g> | <c fis> <b f>8 q | q^( <c e,>) <ais e> q | q^( <b dis,>) <gis d> q | q^( <a! cis,>) <fis c> q | q <g b,>_\markup { \halign #-1 "etc." } } }

\new Voice { \relative b' { \stemDown b8([ e,) a a] | a[ d, d g] | r g[ cis, fis] | r fis[ b, e] | r e[ a, d] } } >> }

\new Staff { \clef bass s2 r4 g8 g | g[ c fis fis] | fis[ b, e e] | e([ a,) d d] | d[ g,] } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/t/2tbglwq0kc1f406jkr3ll357gyhtugm/2tbglwq0.png)

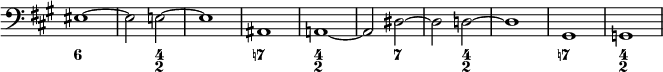

Bach affords some remarkably forcible examples, as in the chorus 'Mit Blitzen und Donner' in the Matthäus Passion, and in the latter part of the Fantasia for Organ in G (Dörffel 855), in which the bass progresses slowly by semitones downwards from C♯ to D. A passage quoted by Marx at the end of the second volume of his Kompositionslehre from the 'Christe Eleison' in Bach's A major[1] Mass is very fine and characteristic; the succession of transitions is founded on a bass which progresses as follows:—

In modern music a common form is that in which the succession of key-notes is by rising or falling semitones, as in the following passage from the first movement of the Eroica Symphony:—

Of this form there are numerous examples in Chopin, as in the latter part of the Ballade in A♭, and in the Prelude in the same key (No. 17). Beethoven makes use of successions of thirds in the same way; of which the most remarkable example is the Largo which precedes the fugue in the Sonata in B♭, op. 106. In this there are fully eighteen successive steps of thirds downwards, most of them minor. This instance also points to a feature which is important to note. The successions are not perfectly symmetrical, but are purposely distributed with a certain amount of irregularity so as to relieve them from the obviousness which is often ruinous to the effect of earlier examples. The divisions represented by each step are severally variable in length, but the sum total is a complete impression based upon an appreciable system; and this result is far more artistic than the examples where the form is so obvious that it might almost have been measured out with a pair of compasses. This point leads to the consideration of another striking device of Beethoven's, namely, the use of a cæsura in modulation, which serves a similar purpose to the irregular distribution of successive modulations. A most striking example is that in the Prestissimo of the Sonata in E major, op. 109, in bars 104 and 105, where he leaps from the major chord of the supertonic to the minor of the tonic, evidently cutting short the ordinary process of supertonic, dominant and tonic; and the effect of this sudden irruption of the original key and subject before the ordinary and expected progressions are concluded is most remarkable. In the slow movement of Schumann's sonata in G minor there is a passage which has a similar happy effect, where the leap is made from the dominant seventh of the key of D♭ to the tonic chord of C to resume the first subject, as follows:—

In the study of the art of music it is important to have a clear idea of the manner in which the function and resources of modulation have been gradually realised. It will be best therefore, at the risk of going occasionally over the same ground twice, to give a short consecutive review of the aspect it presents along the stream of constant production.

To a modern ear of any musical capacity moduation appears a very simple and easy matter, but when harmonic music was only beginning to be felt, the force even of a single key was but doubtfully realised, and the relation of different keys to one another was almost out of the range of human conception. Musicians of those days no doubt had some glimmering sense of a field being open before them, but they did not know what the problems were which they had to solve. It is true that even some time before the beginning of the seventeenth century they must have had a tolerably good idea of the distribution of notes which we call a key, but they probably did not regard it as an important matter, and looked rather to the laws and devices of counterpoint, after the old polyphonic manner, as the chief means by which music was to go on as it had done before. Hence in those great polyphonic times of Palestrina and Lasso, and even later in some quarters, there was no such thing as modulation in our sense of the word. They were gradually absorbing into their material certain accidentals which the greater masters found out how to use with effect; and these being incorporated with the intervals which the old church modes afforded them, gave rise to successions and passages in which they appear to us to wander with uncertain steps from one nearly related key to another; whereas in reality they were only using the actual notes which appeared to them to be available for artistic purposes, without considering whether their combinations were related to a common tonic in the sense which we recognise, or not. Nevertheless this process of introducing accidentals irregularly was the ultimate means through which the art of modulation was developed. For the musical sense of these composers, being very acute, would lead them to consider the relations of the new chords which contained notes thus modified, and to surround them with larger and larger groups of chords which in our sense would be considered to be tonally related; and the very smoothness and softness of the combinations to which they were accustomed would ensure a gradual approach to consistent tonality, though the direction into which their accidentals turned them was rather uncertain and irregular, and not so much governed by any feeling of the effects of modulation as by the constitution of the ecclesiastical scales. Examples of this are given in the article Harmony; and reference may also be made to a Pavin and a Fantasia by our great master, Orlando Gibbons, in the Parthenia, which has lately been republished by Mr. Pauer. In these there are remarkably fine and strong effects produced by means of accidentals; but the transitions are to modern ideas singularly irregular. Gibbons appears to slip from one tonality to another more than six times in as many bars, and to slide back into his original key as if he had never been away. In some of his vocal works he presents broader expanses of distinct tonality, but of the power of the effect of modulation on an extended scale he can have had but the very slightest possible idea. About his time and a little later in Italy, among such musicians as Carissimi and Cesti, the outlines of the modern art were growing stronger. They appreciated the sense of pure harmonic combinations, though they lost much of the force and dignity of the polyphonic school; and they began to use simple modulations, and to define them much as a modern would do, but with the simplest devices possible. Throughout the seventeenth century the system of keys was being gradually matured, but their range was extraordinarily limited, and the interchange of keys was still occasionally irregular. Corelli, in the latter part of it, clearly felt the relative importance of different notes in a key and the harmonies which they represent, and balanced many instrumental movements on principles analogous to our own, though simpler; and the same may be said of Couperin, who was his junior by a few years; but it is apparent that they moved among accidentals with caution, and regarded what we call extreme keys as dangerous and almost inexplorable territory.

In the works of the many sterling and solid composers of the early part of the 18th century, the most noticeable feature is the extraordinary expanse of the main keys. Music had arrived at the opposite extreme from its state of a hundred years before; and composers, having realised the effect of pure tonality, were content to remain in one key for periods which to us, with our different ways of expressing ourselves, would be almost impossible. This is in fact the average period of least modulation. Handel is a fairer representative of the time than Bach, for reasons which will be touched upon presently, and his style is much more in conformity with most of his contemporaries who are best known in the musical art. We may take him therefore as a type; and in his works it will be noticed that the extent and number of modulations is extremely limited. In a large proportion of his finest choruses he passes into his dominant key near the beginning—partly to express the balance of keys and partly driven thereto by fugal habits; and then returns to his original key, from which in many cases he hardly stirs again. Thus the whole modulatory range of the 'Hallelujah' Chorus is not more than frequent transitions from the Tonic key to the key of its Dominant and back, and one excursion as far as the relative minor in the middle of the chorus, and that is all. There are choruses with a larger range, and choruses with even less, but the Hallelujah is a fair example to take, and if it is carefully compared with any average modern example, such as Mendelssohn's 'The night is departing,' in the Hymn of Praise, or 'O great is the depth,' in St. Paul, or the first chorus in Brahms's Requiem, a very strong impression of the progressive tendency of modern music in the matter of modulation will be obtained. In choruses and movements in the minor mode, modulations are on an average more frequent and various, but still infinitely less free than in modern examples. Even in such a fine example as 'The people shall hear,' in Israel, the apparent latitude of modulation is deceptive, for many of the changes of key in the early part are mere repetitions; since the tonalities range up and down between E minor, B and F♯ only, each key returning irregularly. In the latter part it is true the modulations are finely conceived, and represent a degree of appreciation in the matter of relations of various keys, such as Handel does not often manifest.

Allusion has been made above to the practice of going out to a foreign key and returning to the original again in a short space of time. This happens to be a very valuable gauge to test the degrees of appreciation of a composer in the matter of modulation. In modern music keys are felt so strongly as an element of form, that when any one has been brought prominently forward, succeeding modulations for some time after must, except in a few special cases, take another direction. The tonic key, for instance, must inevitably come forward clearly in the early part of a movement, and when its importance has been made sufficiently clear by insistance, and modulations have begun in other directions, if it were to be quickly resumed and insisted on afresh, the impression would be that there was unnecessary tautology; and this must appear obvious on the merest external grounds of logic. The old masters however must, on this point, be judged to have had but little sense of the actual force of different keys as a matter of form; for in a large proportion of examples they were content to waver up and down between nearly-related keys, and constantly to resume one and another without order or design. In the 'Te gloriosus' in Graun's Te Deum, for instance, he goes out to a nearly-related key, and returns to his tonic key no less than five several times, and in the matter of modulation does practically nothing else. Even Bach occasionally presents similar examples, and Mozart's distribution of the modulations in 'Splendente te Deus' (in which he probably followed the standing classical models of vocal music) are on a similar plan, for he digresses and returns again to his principal key at least twelve times in the course of the work.

Bach was in some respects like his contemporaries, and in some so far in advance of them that he cannot fairly be taken as a representative of the average standard of the day. In fact, his more wonderful modulatory devices must have fallen upon utterly deaf ears, not only in his time but for generations after; and, unlike most great men, he appears to have made less impression upon the productive musicians who immediately succeeded him than upon those of a hundred years and more later. In many cases he cast movements in the forms prevalent in his time, and occasionally used vain repetitions of keys like his contemporaries; but when he chose his own lines he produced movements which are perfectly in consonance with modern views. As examples of this the 'Et resurrexit' in the B minor Mass and the last chorus of the Matthew Passion may be taken. In these there is no tautology in the distribution of the modulation, though the extraordinary expanse over which a single key is made to spread, still marks their relationship with other contemporary works. In some of his instrumental works he gives himself more rein, as in fantasias, and preludes, and toccatas, for organ or clavier. In these he not only makes use of the most complicated and elaborate devices in the actual passage from one key to another, but also of closely interwoven transitions in a thoroughly modern fashion. Some of the most wonderful examples are in the Fantasia in G minor for organ (Dörffel 798), and others have been already alluded to.

It is probable that his views on the subject of the relation of keys had considerable influence on the evolution of the specially modern type of instrumental music; as it was chiefly his sons and pupils who worked out and traced in clear and definite outlines the system of key-distribution upon which Haydn and Mozart developed their representative examples of such works.

In the works of these two great composers we find at once the simplest and surest distribution of keys. They are in fact the expositors of the elementary principles which had been arrived at through the speculations and experiments of more that a century and a half of musicians. The vital principle of their art-work is clear and simple tonality; each successive key which is important in the structure of the work is marked by forms both of melody and harmony, which, by the use of the most obvious indicators, state as clearly as possible the tonic to which the particular group of harmonies is to be referred. This is their summary, so to speak, of existing knowledge. But what is most important to this question is that the art did not stop at this point, but composers having arrived at that degree of realisation of the simpler relations of keys, went on at once to build something new upon the foundation. Both Haydn and Mozart—as if perceiving that directly the means of clearly indicating a key were realised, the ease with which it could be grasped would be proportionately increased—began to distribute their modulations more freely and liberally. For certain purposes they both made use of transitions so rapid that the modulations appear to overlap, so that before one key is definitely indicated an ingenious modification of the chord which should have confirmed it leads on to another. The occasions for the use of this device are principally either to obtain a strong contrast to long periods during which single keys have been or are to be maintained; or, where according to the system of form it so happens that a key which has already been employed has soon to be resumed as, for instance, in the recapitulation of the subjects to lead the mind so thoroughly away that the sense of the more permanent key is almost obliterated. Occasionally, when the working-out section is very short, the rapid transitions alluded to are also met with in that position, as in the slow movement of Mozart's E♭ Quartet. The example quoted above from the last movement of his Quartet in C will serve as an example on this point as well as on that for which it was quoted.

A yet more important point in relation to the present question is the use of short breaths of subordinate modulation in the midst of the broader expanses of the principal keys. This is very characteristic of Mozart, and serves happily to indicate the direction in which art was moving at the time. Thus, in the very beginning of his Quartet in G (Köchel 387), he glides out of his principal key into the key of the supertonic, A, and back again in the first four bars. A similar digression, from F to D and back again, may be observed near the beginning of the slow movement of the Jupiter Symphony. But it requires to be carefully noted that the sense of the principal keys is not impaired by these digressions. They are not to be confounded either with the irregular wandering of the composers who immediately succeeded the polyphonic school, nor with the frequent going out and back again of the composers of the early part of the 18th century. This device is really an artificial enlargement of the capacity of a key, and the transitions are generally used to enforce certain notes which are representative and important roots in the original key. A striking example occurs in the first movement of Mozart's symphony in G minor (1st section), where after the key of B♭ has been strongly and clearly pointed out in the first statement of the second subject, he makes a modulatory digression as follows:—

This is in fact a very bold way of enforcing the subdominant note; for though the modulation appears to be to the key of the minor seventh from the tonic, the impression of that key is ingeniously reduced to a minimum, at the same time that the slight flavour that remains of it forms an important element in the effect of the transition.

The great use which Beethoven made of such transitory subordinate modulations has been already treated of at some length in the article Harmony; it will therefore be best here to refer only to a few typical examples. The force with which he employed the device above illustrated from Mozart is shown in the wonderful transition from E♭ to G minor at the beginning of the Eroica (bars 7–10), and the transition from F to D♭ at the beginning of the Sonata Appassionata. These are, as in most of Mozart's examples, only single steps; in many cases Beethoven makes use of several in succession. Thus in the beginning of the E minor Sonata, op. 90, the first section should be theoretically in E minor, but in this case a quick modulation to G begins in the 3rd bar, in the 7th a modulation to B minor follows, and in the 9th, G is taken up again, and through it passage is made back to E minor, the original key, again. Thus the main centre of the principal key is supplemented by subordinate centres; the different notes of the key being used as points of vantage from which a glance can be taken into foreign tonalities, to which they happen also to belong, without losing the sense of the principal key which lies in the background.

These transitions often occur in the early part of movements before the principal key has been much insisted on, as if to enhance its effect by postponement. Thus we find remarkable examples in Beethoven's Introductions, as for instance in the Leonore Overture No. 3, and in the Introduction to the Quartet in C, Op. 59, No. 3. In composers of note since Beethoven, we find a determination to take full advantage of the effect of such transitions. Brahms for instance makes constant use of them in his instrumental works from the earliest to the latest. The first two pages of the G minor Quartet for pianoforte and strings, shows at once how various are the subordinate centres of which he makes use. In a much later work—the Pianoforte Quartet in C minor, op. 60—he presents a short version of his principal subject in the principal key, and then passes to B♭ minor, D♭ major, E♭ minor, A♭, G♭ minor, and B♭ major in rapid succession before he resumes his original key in order to propound his first subject more fully. Schumann was equally free in his use of subordinate modulations. In the fine intermezzo of the 'Faschingsschwank,' which has the signature of E♭ minor, the first chord is in that key, but the second leads to D♭ major, and a few chords further on we are in B♭ minor, from which an abrupt return is made to E♭ minor only to digress afresh. Such are the elaborate transitions which are developed by an extension of the device of single transitions used so frequently by Mozart; and it may be noted that a closely-oonnected series of transitory modulations after this manner, occupies in modern music an analogous position to that occupied by a connected series of harmonies, based on quickly-shifting root-notes, in the music of a century or a century and a half earlier. Similarly, in the closely-connected steps of modulation, like those used by Haydn and Mozart between one strongly marked expanse of key and another, more modern composers have packed their successions of keys so closely that it is often a matter of some difficulty to disentangle them with certainty. For instance, the passage in the slow movement of Beethoven's B♭ Sonata, op. 106, just before the resumption of the principal key and the first subject (in variation), is as follows—

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f << \new Staff { \time 6/8 \key c \minor \relative b' { <bes bes'>4 <g g'>8 q[ <ees ees'>] << { <bes' d f>8 } \\ { f16 aes } >> | <g bes ees g>4 <ces ces'>8 <aes aes'>4 <f f'>8 | <des' des'>4 <bes bes'>8 <g! g'!>4 << { dis'8 <b gis>4 } \\ { r16 <fisis cis> dis8 s } >> gis8 e'4 cis8 \bar "||" \key c \major ais4 <fis' fis'>8 <dis dis'>4 <bis bis'>8 | <gis' gis'>4 <e e'>8 <cis cis'>4 <a! a,!>8 | << { <fis a,>4 } \\ { a,8 ais16 dis } >> dis8 b''4 gis8 | eis4 s } }

\new Staff { \key c \minor \clef bass \relative g, { g16 bes ees g bes ees bes, ees g bes aes f | ees g bes ees aes,, aes' ces, ees aes ces des, des' | bes, des ges bes des, des' ees, g bes des fisis, ais | gis b dis gis bis, dis \clef treble cis e gis cis eis, gis \clef bass \key c \major fis, aes cis fis dis,, dis' fis, ais dis fis gis, gis' | e, gis cis e gis, gis' a,! cis e a cis, cis' | << { r16 fis,8. } \\ { dis4 } >> fisis16 ais gis b dis gis bis, dis | cis4 s } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/t/7/t7sxvpdi5iciaodz6clfrmun410hhq7/t7sxvpdi.png)

In this, besides the number of the transitions (exceeding the number of bars in the example), the steps by which they proceed are noticeable with reference to what was touched upon above in that respect. Many similar examples occur in Schumann's works. For instance, in the last movement of his sonata in G minor, where he wishes to pass from B♭ to G major, to resume his subject, he goes all the way round by B♭ minor, G♭ major, E♭ major, D♭ minor, F♯, B, A, D, C minor, B♭, A♭, and thence at last to G; there is a similar example in the middle of the first movement of his Pianoforte Quartet in E♭; examples are also common in Chopin's works, as for instance bars 29 to 32 of the Prelude in E♭, No. 19, in which the transitions overlap in such a way as to recall the devices of Haydn and Mozart, though the material and mode of expression are so markedly distinct.

From this short survey it will appear that the direction of modern music in respect of modulation has been constant and uniform. The modern scales had first to be developed out of the chaos of ecclesiastical modes, and then they had to be systematised into keys, a process equivalent to discovering the principle of modulation. This clearly took a long time to achieve, since composers moved cautiously over new ground, as if afraid to go far from their starting-point, lest they should not be able to find a way back. Still, the invention of the principle of passing from one key to another led to the discovery of the relations which exist between one key and another; in other words, of the different degrees of musical effect produced by their juxtaposition. The bearings of the more simple of these relations were first established, and then those of the more remote and subtle ones, till the way through every note of the scale to its allied keys was found. In the meanwhile groups of chords belonging to foreign keys were subtly interwoven in the broader expanses of permanent keys, and the principle was recognised that different individual notes of a key can be taken to represent subordinate circles of chords in other keys of which they form important integers, without destroying the sense of the principal tonality. Then as the chords belonging to the various groups called keys are better and better known, it becomes easier to recognise them with less and less indication of their relations; so that groups of chords representing any given tonality can be constantly rendered shorter, until at length successions of transitory modulations make their appearance, in which the group of chords representing a tonality is reduced to two, and these sometimes not representing it by any means obviously.

It may appear from this that we are gravitating back to the chaotic condition which harmony represented in the days before the invention of tonality. But this is not the case. We have gone through all the experiences of the key-system, and by means of it innumerable combinations of notes have been made intelligible which could not otherwise have been so. The key-system is therefore the ultimate test of harmonic combinations, and the ultimate basis of their classification, however closely chords representing different tonalities may be brought together. There will probably always be groups of some extent which are referable to one given centre or tonic, and effects of modulation between permanent keys; but concerning the rapidity with which transitions may succeed one another, and the possibilities of overlapping tonalities, it is not safe to speculate; for theory and analysis are always more safe and helpful to guide us to the understanding of what a great artist shows us when it is done, than to tell him beforehand what he may or may not do.[ C. H. H. P. ]

- ↑ See Bachgesellschaft, 1858, p. 59, 60.