A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Plain Song

PLAIN SONG (Lat. Cantus planus, Cantus Gregorianus; Ital. Canto piano, Canto fermo, Canto Gregoriano; Fr. Plain Chant, Chant Grigorien; Gregorian Chant, Gregorian Music, Plain Chant). A solemn style of unisonous Music, which is believed to have been sung in the Christian Church since its first foundation.

The origin of Plain Song—the only kind of Church Music the use of which has ever been formally prescribed by Ecclesiastical authority—has given rise to much discussion and many diverse theories.[1] On one point, however, all authorities are agreed, viz. that it exhibits peculiarities which can be detected in no other kind of Music whatever; peculiarities so marked, that they can scarcely fail to attract the attention of the most superficial hearer, and so constant, that we shall find no difficulty in tracing them through every successive stage of development through which the system has passed, from the beginning of the Christian Æra to the present time.

Turning, then, to the history of this development, we find that, for nearly four hundred years after its introduction into the Services of the Church, Plain Song was transmitted from age to age by oral tradition only. After the Conversion of Constantino, when Christianity became the established Religion of the Empire, and the Church was no longer compelled to worship in the Catacombs, Schools of Singing were established, for preserving the old traditions, and ensuring an uniform method of singing. A Schola Cantorum of this description was founded at Rome, early in the 4th century, by S. Sylvester, and much good work resulted from the establishment of this and similar institutions in other places. Boys[2] were admitted into them at a very early age, and instructed in all that it was necessary for a devout Chorister to know, under the supervision of a 'Primicerius,' and 'Secundicerius,' of high rank, and well-known erudition; and by this means the primitive Melodies were passed on from mouth to mouth with as little danger as might be of unauthorised corruption. But oral tradition is at best but an uncertain guide; and in process of time the necessity for some safer method of transmission began to excite serious attention. The first attempt to reduce the traditional Melodies to a definite system was made towards the close of the 4th century, by S. Ambrose, Bishop of Milan (ob. 397), who, taking the praxis of the Eastern Church as his model, promulgated a series of regulations which enabled his Clergy to sing the Psalms, Canticles and Hymns, of the Divine Office, with a far greater amount of precision and purity than had hitherto been attainable. It is difficult, now, to determine the exact nature of the work effected by this learned Bishop, though it seems tolerably certain that we are indebted to him for a definite elucidation of the four Authentic Modes, in which alone all the most antient Melodies are written.[3] [See Modes, The Ecclesiastical.] He is also credited with having first introduced into the Western Church the custom of Antiphonal Singing, in which the Psalms are divided, Verse by Verse, between two alternate Choirs, in contradistinction to the Responsorial method, till then prevalent in Italy, wherein the entire Choir responded to the Voice of a single Chorister. Another account, however, attributes its introduction to S. Hilarius, as an imitation of the usage of the Eastern Church, at Poictiers, from whence—and not from Milan—S. Cœlestin is said to have imported it to Rome.

The next great attempt to arrange in systematic order the rich treasury of Plain Song Melodies bequeathed to the Church by tradition, was made, some two hundred years after the death of S. Ambrose, by S. Gregory the Great. The work undertaken by this celebrated reformer was far more exhaustive than that wrought by his predecessor. During the two centuries which had elapsed since the introduction of the Ambrosian Chaunt at Milan, innumerable Hymns had been composed, and innumerable Melodies added to the already lengthy catalogue. All these S. Gregory collected, and carefully revised, adding to them no small number of his own compositions, and forming them into a volume sufficiently comprehensive to suffice for the entire cycle of the Church's Services. The precise manner in which these Melodies were noted down is open to doubt: but, that they were committed to writing, in the celebrated 'Antiphonarium' which has made S. Gregory's name so justly celebrated, is certain; and, though the system of Semiography then employed was exceedingly imperfect, it cannot be doubted that this circumstance tended greatly to the preservation of the Melodies from the corruption which is inseparable from mere traditional transmission. [See Notation.] But we owe to S. Gregory even more than this; for, notwithstanding the objections raised by certain modern historians, it is almost impossible to doubt that it was he who first introduced into the system those four Plagal Modes, which conduce so materially to its completeness, and place the Gregorian Chaunt so far above the Ambrosian in the scale of aesthetic perfection.[4] [See Plagal Modes.]

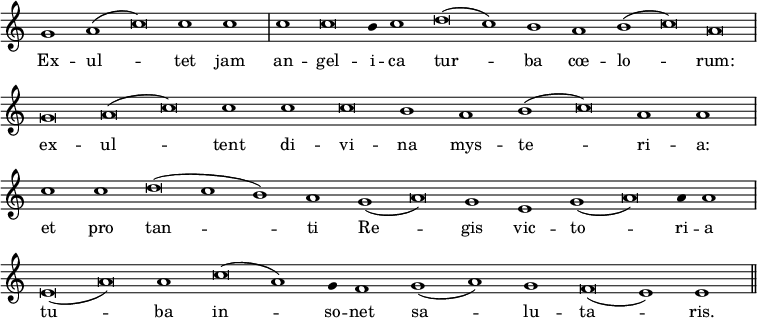

For many centuries after the death of S. Gregory, the 'Antiphonarium' was regarded as the authority to which all other Office-Books must of necessity conform. It was introduced into our own country in the year 596, by S. Augustin, who not only brought it with him, but brought also Roman Choristers to teach the proper method of singing it. The Emperor Charlemagne (ob. 814) commanded its use in the Gallican Church; and it soon found its way into every Diocese in Christendom. Nevertheless, the work of corruption could not be entirely prevented. In the year 1323, Pope John II found it necessary to issue the famous Bull, Docta sanctorum, in order to restrain the Singers of his time from introducing innovations which certainly destroyed the purity of the antient Melody. Cardinal Wolsey complained of the practice of singing Votive Masses 'cum Cantu fracto seu diviso.' Local 'Uses' were adopted in almost every Diocese in Europe. Paris, Aix-la-Chapelle, York, Sarum, Hereford, and a hundred others, had each their own peculiar Office-Books, many of them containing Melodies of undeniable beauty, but all differing, more or less, from the only authoritative norm. After the revision of the Liturgy by the Council of Trent, a vigorous attempt was made to remove this crying evil. In the year 1576, Pope Gregory XIII commanded Palestrina to do the best he could towards restoring the entire system of Plain Song to its original purity. The difficulty of the task was so great, that the 'Princeps Musicæ' left it unfinished, at the time of his death; but, with the assistance of his friend Guidetti, he accomplished enough to render his inability to carry out the entire scheme a matter for endless regret. Under his superintendence, Guidetti published, in 1582, a 'Directorium chori'; in 1586, a 'Cantus Ecclesiasticus Passionis D. N. J. C.'; in 1587, a 'Cantus Ecclesiasticus officii majoris hebdomadæ'; and, in 1588, a volume of 'Præfationes in Cantu firmo'; all printed at Rome, the first 'apud Robertum Gran Ion Parisien,' the three last by Alexander Gardanus. These splendid volumes were, however, anticipated by the production of a splendid folio Antiphonarium, printed at Venice by Pet. Liechtenstein (of Cologne), in 1579–1580. In 1599 the celebrated 'Editio Plantiniana' of the Gradual was issued at Antwerp; while, in 1614–15, the series was closed by the production, at Rome, of the great Medicean edition of the same work, believed to be the purest and most correct which has yet appeared. These fine editions are now exceedingly scarce; but the necessity for a really good series of Office-Books, obtainable at a moderate price, has long been felt, and several attempts have been made to meet the exigencies of the case. In 1848 a Gradual and Vesperal were published at Mechlin, the former based upon the Medicean edition,[5] and the latter, upon the Venice 'Antiphonarium' of 1579–80. Both these works, with an 'Officium Hebdomadæ sanctæ' compiled with equal judgment, have already passed through many carefully revised editions; and, not many years after their appearance, similar volumes were issued by the Archbishops of Rheims and Cambrai, and also by Père Lambillotte, whose Gradual and Antiphonarium were posthumously published in 1857. All these editions were infinitely more correct than the corrupt reprints in general use at the beginning of the present century; and, moreover, they were issued at prices which placed them within the reach of all. Their only fault was a not unnatural clinging to local 'Uses.' This, however, struck at the root of absolute purity: and, to obviate this difficulty, Pope Pius IX empowered the Sacred Congregation of Rites to subject the entire series of Office-Books to a new and searching revision, and to publish them under the direct sanction of the Holy See. In furtherance of this project the first edition of the Gradual was published, under special privileges, by Herr Pustet of Ratisbon, in 1871, and that of the Vesperal in 1875. Other editions soon followed, and we believe the series of volumes is now complete. A comparison of their contents with those of the Mechlin series is extremely interesting, and well exhibits the difference between a Melody corrupted by local 'Use,' and the self-same Strain restored to a better authenticated form, as in the following Verse of the Hymn 'Te Deum laudamus.'

1. From the Mechlin Vesperal (4th ed. 1870).

2. From the Ratisbon Gradual (1871).

We have already seen that Plain Song was introduced into England by S. Augustin, in the year 596. That it nourished vigorously among our countrymen is proved by abundant evidence: but the difference observable between the Sarum, York, and Hereford Office-Books proves that the English Clergy were far from adopting an uniform Use. Some of us, perhaps, may find little to regret in this, seeing that many of the Melodies contained in those venerable tomes—more especially those belonging to the Diocese of Sarum—are of indescribable beauty:[6] yet none the less are such interpolations fatal hindrances to that uniformity of practice which alone can lead to true purity of style. No sooner was the old Religion abolished by Law than the Litany was printed in London, with the antient Plain Song Melody adapted to English words. This work was published by Grafton, the King's printer, on June 16, 1544; and six years later, in 1550, John Marbecke published his famous 'Booke of Common Praier, noted,' in which Plain Song Melodies, printed in the square-headed Gregorian character, are adapted to the Anglicised Offices of 'Mattins,' 'Euen Song,' 'The Communion,' and 'The Communion when there is a Buriall,' with so perfect an appreciation of the true feeling of Plain Song, that one can only wonder at the ingenuity with which it is not merely translated into a new language, but so well fitted to the exigencies of the 'vulgar tongue' that the words and Music might well be supposed to have sprung into existence together.

Except during the period of the Great Rebellion, Marbecke's adaptation of Plain Song to the Anglican Ritual has been in constant use in English Cathedrals from the time of its first publication to the present day. Between the death of Charles I. and the Restoration, all Music worthy of the name was banished from the Religious Services of the Anglican Church; but, after the Accession of Charles II, the practice of singing the Plain Song Versicles and Responses, was at once resumed, but the Gregorian Tones to the Psalms fell into entire disuse, giving place in time to a form of Melody, of a very different kind, known as the 'Double Chaunt.' This substitute for the time-honoured inflections of the more antient style reigned with undisputed sway, both in English Cathedrals, and Parish Churches, until long after the beginning of the present century. Little more than thirty years have elapsed since the first attempts were made to dethrone it. The campaign was opened by Mr. W. Dyce, who, in 1843–44, brought out his 'Book of Common Prayer Noted,' on the system of Marbecke, in two splendid quarto volumes, which, unfortunately, were much too costly for general use. Mr. Oakeley soon afterwards published his 'Laudes Diurnæ,' containing the Psalms and Canticles, adapted to Gregorian Tones, for the use of Margaret Street Chapel.[7] A more important step was taken by the Rev. Thomas Helmore, who produced his 'Psalter and Canticles Noted' in 1850, his 'Brief Directory of Plain Song' in the same year, and his 'Hymnal Noted' in 1851. These works, more especially the first, obtained immediate recognition. The 'Psalter and Canticles' and the 'Brief Directory' were used with striking effect at S. Mark's College, Chelsea, which soon came to be regarded as a sort of normal School of Gregorian Singing: and, at the Church of S. Barnabas, Pimlico, not these two works only, but the 'Hymnal Noted' also, became as familiar to the Congregation as is now the popular Hymnbook of the present day. Since that time adaptations of Plain Song to English words have appeared in numbers calculated rather to confuse than to assist the well-wishers of the movement. Warmly encouraged by the so-called 'High Church Party,' and willingly accepted by the people, 'Gregorians' now form the chief attraction at almost every 'Choir Festival' in the country, are sung with enthusiasm in innumerable Parish Churches, and frequently heard even in Cathedrals.

Having now presented our readers with a rapid survey of the history of Plain Song, from its first appearance in the Christian Church, to the present day, we shall proceed to treat, with equal brevity, of its laws, its constitution, and its distinctive character.

Plain Song Melodies are arranged in several distinct classes, each forming part of a comprehensive and indivisible scheme, though each is marked by certain well-defined peculiarities, and governed by its own peculiar laws. Of these Melodies, the most important are the Tones, or Chaunts, adapted to the Psalms a series of Inflections usually described by modern writers as the 'Gregorian Tones,' though four of them, at least, might be more fairly called 'Ambrosian.' [See Tones, the Gregorian.] That the Psalm Tones are by far the most antient examples of Ecclesiastical Music in existence, has never been doubted. In structure they are nothing more than the simplest imaginable Chaunts, each written in one of the first eight Modes, from which it derives its name or rather, number and each consisting of two distinct members, corresponding to the two responsive phrases into which, in accordance with the well-known laws of Hebrew Poetry, the Verses of the Psalms are often divided, while, in nearly every case, the final Cadence, or 'Ending,' is invested, for the sake of variety, with several different forms. The First, Third, Fifth, and Seventh Tones, representing the four Authentic Modes, are represented by tradition to have been the only ones used by S. Ambrose [see Modes, the Ecclesiastical"); and to these, S. Gregory is said to have added the Second, Fourth, Sixth, and Eighth, each written in a Plagal Mode: but more than one writer on the subject is of opinion that these last-named Tones were in common use long before the time even of S. Ambrose. [See Plagal Modes.] It is, in fact, impossible to trace back the eight familiar forms to the time of their first adoption into the Services of the Church; and still more so, to account for the origin of a supplementary form, which, though unquestionably written in the Ninth, or Æolian Mode, is uniformly described, not as the Ninth Tone, but as the 'Tonus Peregrinus.' [See Tonus Peregrinus.]

Every Psalm and Canticle sung in the Divine Office is accompanied by an Antiphon, which, on Festivals, precedes and follows it, but, on Ferias, follows it only. Antiphons, selected from Holy Scripture, and other sources, are appointed for every Feast, Fast, and Feria, in the Ecclesiastical Year; and each is provided with its proper Plain Song Melody, which will be found in Antiphonarium Romanum.' It is indispensable, that, in every case, the Psalm and Antiphon should be suug in the same Mode; the Tone for the Psalm is therefore suggested by the Mode of the Antiphon; and, as the Psalm Tones—if we except the Tonus Peregrinus, with which we are not now concerned—are written in the first eight Modes only, it follows that the Melodies proper to the Antiphons must necessarily conform to the same rule. Some of these Melodies are extremely beautiful. They are of later date, by far, than the Psalm Tones, and much more elaborate in construction; but they are, none the less, models of the purest Ecclesiastical style. [See Antiphon.]

Next in importance—and, probably, in antiquity also—to the Psalm Tones, are the Inflections used for the Versicles and Responses proper to the Liturgy and the Divine Office; such as the 'Deus in adjutorium' at Vespers, the 'Dominus vobiscum,' and 'Per omnia sæcula sæculorum,' in the 'Ordinarium Missæ,' and other similar passages. All these are exceedingly simple, and bear strong evidence of very high antiquity. [See Responsorium; Versicle.]

Intimately connected with them are the various Accents which collectively constitute the 'Tonus Orationis,' the 'Tonus Lectionis,' the 'Tonus Capituli,' the 'Tonus Prophetiæ,' the 'Tonus Epistolæ,' and the 'Tonus Evangelii.' Each Accent is, in itself, a mere passing Inflection, consisting of two, or at most three notes; but the traditional commixture of the various forms gives to each species of Lection a fixed character which never fails to adapt itself to the spirit of the text. [See Accents.]

More elaborate than any of the forms we have hitherto described, and, no doubt, of considerably later date, are the Melodies adapted to certain portions of the Liturgy, which have been sung at High Mass from time immemorial. We shall first discuss those belonging to the 'Proprium Missæ'—i.e. that part of the Mass which varies on different Festivals.

The first, and one of the most important, of these, is the Introit; which partakes, in about equal degrees, of the characters of the Antiphon and the Psalm Tone. The words of the Introit are divided into two portions, of which the first is a pure Antiphon, and the second, a single Verse of a Psalm, followed by the 'Gloria Patri,' after which the Antiphon is again repeated in full. Except that it is perhaps a little more elaborate, the Melody of the first division differs but little, in style, from that proper to the Antiphons sung at Lauds and Vespers; and, for the reasons we have mentioned in speaking of these, it is always written in one of the first eight Modes. The Verse of the Psalm, and its supplementary 'Gloria Patri,' are sung to the Tone which corresponds with the Mode of the Antiphon; but, in this case, the simple Melody of the original Chaunt, though permitted to exhibit one single 'Ending' only, is developed into a far more complicated form, by the introduction of accessory notes, which would be altogether out of place at Vespers, when five long Psalms are sung continuously, though they add not a little to the dignity of this part of the Mass. The Antiphon is then repeated exactly as before, care being taken to sing it in a style which may contrast effectively with the preceding Chaunt; and, in Paschal Tide, this is followed by a double Alleluia, of which eight forms are given in the Graduale, one in each of the first eight Modes. [See Introit.]

The Gradual, though consisting, like the Introit, of two distinct members the Gradual proper, and the Versus—differs from it in that no part of it is recited, after the manner of a Psalm, upon a single note. The Melody, throughout, bears a close analogy to that of the more elaborate species of Antiphon, as exhibited in the first part of the Introit: and its two sections, though always written in the same Mode, are quite distinct from each other, and never repeat the same phrases. [See Gradual.]

On Festivals, the Gradual is supplemented by a form of Alleluia peculiar to itself, which, in its turn, is followed by another Versus, wherefrom it takes its Mode, and after which it is again repeated, after the manner of a Da Capo. This Alleluia is twice repeated, and then echoed, as it were, by an elaborate Pneuma, in the same Mode. [See Pneuma.] The style of the Versus corresponds exactly with that of the Gradual; and, after that has been sung, the Alleluia and Pneuma are repeated as before.

Between the Seasons of Septuagesima and Easter, the Alleluia, and Versus, are omitted, their place being supplied by a Tractus, with one or more Versus attached to it, the music of which corresponds exactly, in style, with that of the Gradual and Versus already described.

On the Festivals of Easter, Pentecost, Corpus Christi, and the Seven Dolours of our Lady, and also at Masses for the Dead, the Gradual is followed by the Sequentia, or Prosa—a species of Hymn of which a great many examples were once in existence, though five only now remain in use. These five are the well-known 'Victimæ Paschali,' 'Veni Sancte Spiritus,' 'Lauda Sion,' Stabat Mater,' and 'Dies iræ'—a series of Hymns which, whether we regard their quaint mediæval versification, or the Music to which it is adapted, may safely be classed among the most beautiful that ever were written. [See Prosa; Sequentia.] Compared with the Melodies we have been considering, those of the Sequences are of very modern origin indeed. The tuneful rhymes of 'Veni Sancte Spiritus'—known among mediaeval writers as the 'Golden Sequence'—were composed by King Robert II of France, about the year 1000. 'Victimiæ Paschali' is probably of somewhat later date. The 'Dies iræ' was written about the year 1150, by Thomas of Celano, while the 'Lauda Sion' of S. Thomas Aquinas can scarcely have been produced before the year 1260. In all these cases, the Plain Song Melody was undoubtedly coæval with the Poetry, if not composed by the same author; and we are not surprised to find it differing, in more than one particular, from the Hymns collected by S. Ambrose and S. Gregory. Four out of the five examples now in use are in mixed Modes; and, in every instance, the Melody exhibits a symmetry of construction which distinguishes it alike from the Antiphon and the Hymn. From the former, it differs in the regularity of its rhythm, and the constant repetition of its several phrases; from the latter, in the alternation of these phrases with one another; for, while the Verses of the Hymn are all sung to the same Melody, those of the Sequences are adapted to two or more distinct Strains, which are frequently interchanged with each other, almost after the manner of a Rondo, a peculiarity which is also observable in some very fine, though now disused Sequences, which were removed from the Missal on its final revision by the Council of Trent.

The style of the Offertorium differs but little from that of the Gradual, though it is sometimes a little more ornate, and makes a more frequent use of the Perielesis. Like the Gradual, it is sometimes—as in the 'Missa pro Defunctis'—followed by a Versus; but it more frequently consists of a single member only, without break or repetition of any kind. In Paschal Tide, however, it is followed by a proper Alleluia in its own Mode. [See Offertorium; Perielesis.]

The last portion of the 'Proprium Missæ' for which a Plain Song Melody is provided in the Office-Books is the Communio. This is usually much shorter than either the Gradual or the Offertory; from which it differs in style so slightly as to need no separate description. It is followed, in Paschal Tide, by a proper Alleluia, which, of course, conforms to its own proper Mode.

The 'Ordinarium Missæ'—i.e. that part of the Mass which is the same on all occasions—is preceded, on Sundays, by the Asperges, which exactly resembles the Introit, both in the arrangement of its words, and the style of its Music an extremely beautiful instance of the use of the Seventh Mode.

Of the Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus, Benedictus, and Agnus Dei, the Ratisbon Gradual gives ten Plain Song versions, in different Modes, and adapted to Festivals of different degrees of solemnity; besides three Ferial Masses, in which the 'Gloria' is not sung, and the beautiful 'Missa pro Defunctis.' The Mechlin Gradual gives eight forms only for Festivals, and one for Ferial Days. Of the Credo, four versions are given, in each volume. It is impossible even to guess at the date of these fine old Melodies, some of which are exceedingly complicated in structure, while others are comparatively simple. The shorter movements, such as the Kyrie and Sanctus, are sometimes very highly elaborated, with constant use of the Perielesis, even on two or more consecutive syllables; while the Gloria and Credo are developed from a few simple phrases, frequently repeated, and arranged in a form no less symmetrical than that we have described as peculiar to the Sequence, though the alternation of strains, which serves as the distinguishing characteristic of that form of Melody, is carried out in a somewhat different way.

The oldest known copy of the Sursum Corda and Prefaces dates from the year 1075. The style of these differs very materially from that of the other portions of the Mass, and, like that of the Pater Noster, is distinguished by a grave dignity peculiarly its own. In addition to these, the repertoire is enriched by certain proper Melodies which are heard once only during the course of the Church's Year; such as the Ecce lignum Crucis and Improperia, appointed for Good Friday; and more especially, the Exultet, sung during the blessing of the Paschal Candle on Holy Saturday. This truly great composition is universally acknowledged to be the finest specimen of Plain Song we possess. It is written in the Tenth, or Hypoæolian Mode; and is of so great length, that few Ecclesiastics, save those attached to the Pontifical Chapel, are able to sing it, throughout, without a change of pitch fatal to the perfection of its effect; yet, though it is developed, like the 'Credo,' and some other Melodies we have noticed, from a few simple phrases, often repeated, and woven, with due attention to the expression of the words, into a continuous whole, the last thought one entertains, during its performance, is that of monotony or weariness. The first phrase, which we here transcribe, will perhaps suffice to give the reader a good idea of the general effect of the whole.

Very different in style from the 'Exultet' is the wailing Chaunt, in the devoutly sad Sixth Mode, to which, in the Pontifical Chapel, the Second and Third Lessons, taken from the Lamentations of Jeremiah, are sung on the three last days in Holy Week. The Chaunt for the Lamentations, which will be found reduced to modern Notation at page 86 of the present volume, stands as much alone as the more jubilant Canticle; but in its own peculiar way. While the one represents the perfection of triumphant dignity, the other carries us down to the very lowest depths of sorrow; and is, indeed, susceptible of such intensely pathetic expression, that none who have ever heard it sung, in the only way in which it can be sung, if it is intended to fulfil its self-evident purpose,—that is to say, with the deepest feeling the Singer can possibly infuse into it,—will feel inclined to deny its title to be regarded as the saddest Melody within the whole range of Music.

Well contrasted with this are the Antiphons and Responsoria for the same sad days—the former far more simple generally, than Antiphons usually are, while the Responsoria are often graced with Perieleses of great beauty.

Upon these, and many minor details, we would willingly have dwelt at greater length; but have now no choice but to proceed, in the last place, to speak of the Hymns included in the Divine Office. The antiquity of these varies greatly, their dates extending over many centuries. Among the oldest are those appointed in the Roman Breviary for the ordinary Sunday and Ferial Offices, and the Lesser Hours. The more antient examples are adapted, for the most part, to simple Melodies, in which Ligatures, even of two notes, are of rare occurrence, a single note being, as a general rule, sung to every syllable. Of these, the well-known inspirations of Prudentius, 'Ales diei nuntius,' 'Lux ecce surgit aurea,' 'Nox et tenebrae,' 'Salvete flores martyrum,' and a few others, date from about the year 400. 'Crudelis Herodes,' and 'A solis ortus cardine,' by Sedulius, were probably written some twenty years later. 'Rector potens, verax Deus,' 'Rerum Deus tenax vigor,' 'Æterne Rex altissime,' and a few others, are also generally referred to the 5th century; 'Audi, benigne Conditor,' and 'Beati nobis gaudia' to the 6th. 'Pange lingua gloriosi,' and 'Vexilla Regis prodeunt,' were written by S. Venantius Fortunatus, about the year 570. 'Te lucis ante terminum,' and 'Iste Confessor' are believed to date from the 7th century; 'Somno refectis artubus' from the 8th; and 'Gloria, laus, et honor,' from the 9th. Of the later Hymns, 'Jesu dulcis memoria' was composed by S. Bernard in 1140; and 'Verbum supernum prodiens' by S. Thomas Aquinas, not earlier than 1260. Hymn-melodies of later date frequently exhibit long Ligatures of great beauty; and, as a rule, the more modern the Hymn, the more elaborate is the Music to which it is adapted; though it does not follow that it is to be preferred, on that account, to the rude but dignified strains peculiar to a more hoary antiquity.

Leaving the student to cultivate a practical acquaintance with the various forms of Plain Song to which we have directed his attention, by referring to the Melodies themselves, as they stand in the Graduale, Vesperale, and Antiphonarium Romanum, it remains only for us to offer a few remarks upon the manner in which this kind of Music may be most effectively performed.

As a matter of course, the Priest's part, in Plain Song Services of any kind, must be sung without any harmonised Accompaniment whatever, care only being taken that the pitch chosen for it may coincide with that necessarily adopted by the Choir, when it is their duty to respond in Polyphonic Harmony. For instance, if the 'Sursum corda,' and 'Preface,' be unskilfully managed in this respect, an awkward break will seriously injure the effect of the 'Sanctus '; while the 'Gloria' and 'Credo' will lose much of their beauty, if equal care be not bestowed upon their respective Intonations. No less judgment is required in the selection of a suitable pitch for the far more difficult 'Exultet,' the first division of which is interupted by a form of 'Sursum corda,' analogous to that which precedes the 'Preface': and, in all cases, a perfect correspondence of intention between Priest and Choir is absolutely indispensable to the success of a Plain Song Service.

The 'Kyrie,' 'Gloria,' 'Credo,' and other movements pertaining to High Mass, may be sung in unison, either by Grave, or Acute Equal Voices, and either with, or without, a fitting Organ Accompaniment. It must, however, be understood that unison, in this case, does not mean octaves. The clauses of the 'Gloria' and 'Credo' produce an excellent effect, when sung by the Voices of Boys and Men alternately: but, when both sing together, all dignity of style is lost in the general thinness of the resulting tone. This remark applies with equal force to the Psalms sung at Lauds and Vespers, and even to the Hymns. In the Pontifical Chapel, the Verses are entrusted either to Sopranos or Altos in unison, or to Tenors and Basses; alternated, on certain occasions, with the noblest and most severe forms of Faux Bourdon—of course unaccompanied. At Notre Dame de Paris, and S. Sulpice, one Verse of a Psalm, or Canticle, is very effectively sung by Tenors and Basses in unison, and one in Faux Bourdon; both with a grand Organ Accompaniment, which, when well managed, by no means destroys the peculiar character of the antient Melody, though it is undoubtedly preferable, that, wherever it is possible to dispense with the instrumental support, the Voices should be left to themselves. The misfortune is, so very few Organists are willing to confine themselves to the only Harmonies with which Plain Song can be consistently accompanied. The Ecclesiastical Modes are wholly unsuited to diversified combinations, which have no more affinity with them than mediæval architecture with that of the Parthenon: and the needless introduction of Diminished Sevenths and Augmented Sixths into the Accompaniment of the Psalms is as grave an offence against good taste as would be the erection of a Doric Pediment in front of Westminster Abbey. Until this fact is generally recognised, there will always be a prejudice against Plain Song among those who judge by results, without troubling themselves to enquire into the causes which produce them: for no well-trained ear can listen to a 'Gregorian Psalm,' with Chromatic Accompaniment, without a feeling of disgust akin to that which would be produced by the association of Chopin's wild Melodies with the Harmonies of Orlando Gibbons.[8]

On the other hand, an intimate connection exists between Plain Song and true Polyphony—which indeed was originally suggested by and owes its very existence to it. Almost every class of Melody we have described has been treated by the Great Masters in Counterpoint of more or less complexity; and that, so frequently, that we possess Polyphonic renderings of the Music used at High Mass, at Solemn Vespers, and in the awful Services of Holy Week, in quantity sufficient to supply the needs of Christendom throughout the entire cycle of the Ecclesiastical Year. The Psalm Tones have been set, by Bernabei, and other learned Contrapuntists, with a full appreciation of the grave simplicity of their style, and a careful adaptation of the four- and five-part Harmony of the mediæval Schools to the Modes in which they are written: and Palestrina, Felice Anerio, the two Nanini, Luca Viadana, and a host of their contemporaries, have supplemented them with innumerable original Faux Bourdons intended to alternate with unisonous Verses of the simple Chaunt.[9] A fine MS. collection of them was discovered, in Rome, by Dr. Burney, whose autograph copy of it is now preserved, in the Library of the British Museum, under the title of 'Studij di Palestrina'; and many others are in existence, both in MS. and in print. Of works of greater pretension, the number is inexhaustible. iVithout reckoning the great Masses and Motets founded on Plain Song Canti fermi, which naturally fall into another category, we possess no end of harmonised Plain Song, in the form of Litanies, Responses, Hymns, and other movements of inestimable value. Some of the finest of them will be found among the 'Cantionea sacræ' of Tallis and Byrd; but, for the most perfect work of the kind we possess, we are inlebted to the genius of Palestrina, whose 'Hymni totius anni,' published at Rome by F. Coattinus, in 1589, contain a series of forty-five of the Hymns most frequently sung in the various Offices of the Church, in each of which the antient Canto fermo is made to serve as the basis of a composition of the rarest beauty, no less remarkable for the skill displayed in its construction, than for the true artistic feeling with which that skill is concealed beneath the rugged grandeur of the original Melody. [See Hymn, vol. i. 7606.]

We find ourselves, then, after the lapse of more than eighteen centuries, in possession of a treasury of Plain Song, rich enough to supply the Church's every need, so long as her present form of Ritual remains in use, and sufficiently varied to adapt itself to any imaginable contingency. Though we can bring forward no evidence old enough to enable us to trace back the earliest of our treasures to their origin, and thus establish their purity beyond all possibility of doubt, the comparison of innumerable mediæval MSS. justifies us in believing that the materials which have been handed down to us have suffered far less deterioration than might reasonably have been expected, when their extreme antiquity is taken into consideration. The scrupulous care which has been bestowed upon these MSS. within the last thirty years leaves little room for fear that the written text will be corrupted in time to come: but, that the style of performance is neither free from present corruption, nor from the danger of still greater abuses in the future, is only too painfully evident. Those, then, who are really in earnest in their desire to preserve both the letter and the spirit of our store of antient Melodies from unauthorised interference, will do well to fortify their own taste and judgment by careful study; remembering, that, however worthy of our reverence the true Music of the Early Christian Church may be, modernised Plain Song is an abomination which neither gods nor men can tolerate.[ W. S. R. ]

- ↑ Consult, for the different views:—(1) P. Martini, 'Storia della Musica.' Tom. i. pp. 350, et seq.; Gerbert, 'De Cantu et Mus. Sacr.'; Coussemaker, 'Memoire sur Hucbald,' pp. 5–7; Père Lambillotte, 'Esthétique theor. et prat. du Chant Gregorien,' p. 14; Jakob, 'Die Kunst im Dienste der Kirche.' p. 193, etc. etc. (2) Menestrier, 'Traité des Representations en Musique, anciennes et modernes.' (3) Rousseau. 'Ce Chant, tel qu'il subsiste encore aujourd'hui, est un reste bleu défiguré, mais bien précieux, de l'ancienne Musique Grecque.' (Dict, de Mus., art. Plain-Chant.) Consult also Mersennus, 'Harmon. universelle.' (4) 'Ambros, Geschichte der Musik.' ii. 11. (5) Forkel. 'Allgemeine Geschichte der Musik.' Tom. ii. p. 91. See also Kiesewetter. 'Geschichte der Europ.-abendländischen Musik,' Introd. p. 2.

- ↑ Mostly orphans whence the Schools were called 'Orphanotropia.' (Anastasius Bibliothecarius, in vit. Sergii II. Pontif.)

- ↑ Consult, on this subject, a tract by the R. P. Cam. Perego, entitled 'La regola del Canto Fermo Ambrosiano.' (Milano, 1022.)

- ↑ It has been objected to this, that the so-called 'Ambrosian Te Deum' is in the Mixed Phrygian Mode—which is true. But it has yet to be proved that the Melody, as we now possess it, exhibits the exact form in which it was left by S. Ambrose.

- ↑ Except in the 'Ordinarium Missæ,' which followed the Editio Plantiniana.

- ↑ Witness the glorious Melody to 'Sanctorum meritis' (printed in the Rev. T. Helmore's 'Hymnal Noted'), which finds no place in the 'Vesperale Bomanum.'

- ↑ Now the Church of All Saints', Margaret Street.

- ↑ Forbidden Harmonies may be found, in no small number, even in some of the publications issued at Ratisbon, since the death of Dr. Proske, who, himself, was the most conscientious of editors, and tolerated no compromise with impurity of any kind.

- ↑ A large collection of these will be found in Proske's 'Musica Divina,' Tom. iii.