A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Wrist Touch

WRIST TOUCH (Ger. Handgelenk). In pianoforte playing, detached notes can be produced in three different ways, by movement of the finger, by the action of the wrist, and by the movement of the arm from the elbow. [Staccato.] Of these, wrist-touch is the most serviceable, being available for chords and octaves as well as single sounds, and at the same time less fatiguing than the movement from the elbow. Single-note passages can be executed from the wrist in a more rapid tempo than is possible by means of finger-staccato.

In wrist-touch, the fore-arm remains quiescent in a horizontal position, while the keys are struck by a rapid vertical movement of the hand from the wrist joint. The most important application of wrist-touch is in the performance of brilliant octave-passages; and by practice the necessary flexibility of wrist and velocity of movement can be developed to a surprising extent, many of the most celebrated executants, among whom may be specially mentioned Alexander Dreyschock, having been renowned for the rapidity and vigour of their octaves. Examples of wrist octaves abound in pianoforte music from the time of Clementi (who has an octave-study in his Gradus, No. 65), but Beethoven appears to have made remarkably little use of octave-passages, the short passages in the Finale of the Sonata in C, Op. 2, No. 3, and the Trio of the Scherzo of the Sonata in C minor for Piano and Violin, Op. 30, No. 2, with perhaps the long unison passage in the first movement of the Concerto in E♭ (though here the tempo is scarcely rapid enough to necessitate the use of the wrist), being almost the only examples. A fine example of wrist-touch, both in octaves and chords, is afforded by the accompaniment to Schubert's 'Erl King.'

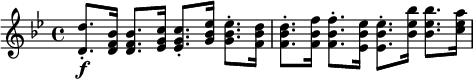

In modern music, passages requiring a combination of wrist and finger movement are sometimes met with, where the thumb or the little finger remains stationary, while repeated single notes or chords are played by the opposite side of the hand. In all these cases, examples of which are given below, although the movements of the wrist are considerably limited by the stationary finger, the repetition is undoubtedly produced by true wrist-action, and not by finger-movement. Adolph Kullak (Kunst des Anschlags) calls this 'half-wrist touch' (halbes Handgelenk).

Schumann, 'Reconnaisance' (Carneval).

Thalberg, 'Mose in Egitto.'

In such frequent chord-figures as the following, the short chord is played with a particularly free and loose wrist, the longer one being emphasized by a certain pressure from the arm.

Mendelssohn, Cello Sonata (Op. 45).