Horse shoes and horse shoeing: their origin, history, uses, and abuses/Chapter IV

CHAPTER IV.

In Switzerland, as has been noticed, shoes of the form peculiar to the Celtic, Roman, and subsequent periods, have been found. Those discovered by M. Troyon[1] in the supposed sacrificial mound of Chavannes, have been described as differing only in the absence of calkins from the majority of those already considered. They were five in number, and very primitive in shape. Their measurement appears to have been—length, 4½ inches; width, 4⅓ inches. The strongest branch, which may be looked upon as that for the outer border of the hoof, had the holes punched coarsely (that is, farther from the external border); and the inner or weaker branch, finer, or nearer the outer edge. The holes were a little more rectangular than is usually seen in these primitive specimens. M. Troyon was in doubt as to the epoch to which this mound, and the bones, spurs, bits, and other articles, belonged; but elsewhere he appears to refer the shoes to the second 'iron age,' or the Helveto-Roman period[2] (see fig. 22). In speaking of these articles, this able antiquarian remarks: 'A horse-shoe has been discovered, with arrow-heads and lances, in a tumulus in the neighbourhood of Aussée, which appears to me to resemble that of Chavannes. Another has been found in a tumulus in the Canton Berne, but its form is exactly that of those met with in the Roman ruins. We see horse-shoes like those of Chavannes, but of more advanced workmanship, from the battle-field of Cressy, and preserved in the Artillery Museum of Paris.'[3] Baron Bonstetten gives a drawing of a fragment of a shoe of this description, obtained by workmen who were demolishing a tumulus standing between Sariswyl and Murzelen, Canton Berne. It is merely the toe-piece of the shoe, without holes or any other indication of its antiquity. In three other tumuli explored by this archæologist, arms and several objects in bronze were recovered, which were classed as belonging to the Helveto-Roman age.[4]

The Museum of Avenches exhibits many shoes obtained from the Roman ruins of Avencium, the ancient capital of Helvetia. They have all, with one exception, six nail-holes; the largest has eight.[5] In the excavations made at Grange, near Cossonay (Canton Vaud), relics of the same kind have been picked up. The figure of one designed by M. Bieler, gives its size as barely 4 inches in length and 3 inches in breadth (fig. 27). It has low calkins, and a slight groove runs from heel to heel. Altogether, it looks a much more recent shoe than any of those usually ascribed to the Celtic or Gallo-Roman age; though M. Bieler is of opinion that it belongs to the third century. A specimen in the Berne Museum, and which was dug out of a tumulus at Garchwyl, near Berne,, does not differ much in appearance from the last. It was found with a very fine specimen of a vase and other articles, but their age is uncertain. The tumulus was supposed to be very old—anterior, it was surmised, to our era, and at any rate not dating any later than the third or fourth century.[6] In appearance it is more modern, and is chiefly remarkable for having the groove passing continuously from toe to heel—in having four nail-holes on one side and three on the other, and showing also a toe-piece with six marks proceeding from it (fig. 28).[7] The Roman camp on Mount Terrible has also furnished a number, which are in the private museum of M. Quiquerez. M. Bieler thus sums up the general characteristics of the shoes he has examined: 'The shoes of the Roman epoch have usually six holes (étampures), and very rarely the largest have eight.These rectangular holes are generally distributed along a groove analogous to that of the Enlish shoes, and without interruption at the toe; but the holes are much larger than the grooves, and cause bulgings on the external border. The ajusture (fitting to the shape of the foot's surface) is null, or nearly so. Lastly, the heels are rolled over in some shoes, others have rude calkins, and some have also a crampon, or toe-piece. With regard to the nails, they differ essentially from our own, and are more of the Arab form. The head is flat, about half a line in thickness; its shape is nearly semicircular, and it is from one-half to three-quarters of an inch in diameter; the shank or body (lame) is square and rather strong. When the head has been worn to the surface of the shoe, the part buried in the cavity of the aperture is in outline like a T.'

From the excellent memoir on the horse-shoes found in the Jura Alps, by M. Quiquerez,[8] who has distinguished himself by his researches into the situation and mode of working the Celtic forges, we will make a few extracts, which are perhaps as satisfactory as they are lucid. 'For a long time,' he says, 'there have been remarked various kinds of horse-shoes in the monuments belonging to several ages, without our having been able until the present time to make them serve as a guide to recognize with precision the period in which they were used. They have also been collected from the pastures, forests, and cultivated lands, at such depths that it could not be admitted they belonged to modern times. Some particular forms, and especially the diminutiveness of these shoes, indicated a smaller race of horses, or a breed with small feet, such as are yet noticed in certain kinds of well-bred animals. At any rate, the meagre quantity of metal employed seemed to point to a light race, or perhaps the scarcity of iron, or even these two causes combined. It is very remarkable that these small shoes are not limited to one portion of the Swiss Jura, but are found from the banks of the Rhine to Geneva, throughout the whole extent of the Alps, on both its slopes, as well as in its central valleys. We may then be assured that these are the shoes of the indigenous horses which have pastured over the whole of this country at various periods, during a long space of time. They ought, therefore, to afford a characteristic index of those Gaulish horses so renowned in bygone ages, but which have been modified by crossing with strange breeds during the Roman and barbarian conquests. A more attentive study of these shoes, and of the localities from whence they were procured, permits their being divided into at least two classes, belonging, if not to different epochs, at least to people shoeing their horses diversely in the same country. These differences of form correspond also to an augmentation in size, thickness, and weight, and in such a way that those we look upon as the most ancient weigh scarcely more than from 90 to 120 grammes;[9] while those of the following ages also increase in weight and dimensions, so that for the time of the Romans they reach from 180 to 245 grammes; then to 365: lastly, in our own days, they weigh from 490 to 850 grammes, and even more. These modest objects of antiquity thus reveal facts no less interesting to archæology than to agriculture. Under the last head they seem to indicate a progressive augmentation in the height of the horses, and an amelioration in the indigenous species, arising from the progress of agriculture and commerce, as the two began to require horses with more strength than elegance or lightness. In an archæological point of view, they furnish a material proof of the persistence of the usages of a country in its mode of shoeing horses; so that the invasions and foreign occupations could not cause them to be entirely abandoned by our native farriers. This last fact also testifies to the existence of the same people in these regions, and their surviving the Roman and barbarian domination. Nevertheless, it is not only the permanence of the shape of the horse-shoes which has given rise to this opinion, but also the persistence that the people and the artisans of the country have shown in the reproduction of the forms of ordinary articles, instruments, or arms; and to such a degree is this the case, that the hatchets of stone, for example, and those of bronze and iron, are found, after long intervals, to be so similar in form and dimensions that the difference of material could not be taken into account. This evidently proves the influence of habit in the use of utensils of a certain form. The hatchet of bronze remains as small as that of stone; and it is the same with the weapon made of iron—apparently for the same reason, that the untempered instrument of iron was scarcely better than the one made of bronze. Drawings of Roman antiquities and those of the middle ages represent iron arrow-heads, keys, knives, and designs of vases, which are exactly the same. The same fact is noticed in certain details in architecture; for instance, the church of Moutiers-Grand-Val, built in the 7th century, we find the same details that may yet be discerned in the theatre of Mandeura.

'The shoes we look upon as the oldest, show, to commence with, that the Celts were already acquainted with siderurgy; the examination we have made of the ancient forges in the Jura furnishes us with important indications in this respect, (More than 160 siderurgical establishments of various epochs have been already discovered, and some of them have furnished antique objects which serve to determine the age of the iron. The furnaces and crucibles disinterred by us are peculiar in form, and appear to testify that the use of the blast to hasten the combustion of the fuel was then unknown.)'

It may here be remarked that Mr T. Wright shows that the Romans in Britain smelted their iron very imperfectly. 'It is supposed that layers of iron ore, broken up, and charcoal mixed with limestone as a flux, were piled together, and enclosed in a wall and covering of clay, with holes at the bottom for letting in the draught, and allowing the melted metal to run out. For this purpose they were usually placed on sloping ground. Rude bellows were, perhaps, used, worked by different contrivances.' Mr Bruce, in his account of the 'Roman Wall,' has pointed out a very curious contrivance for producing a blast in the furnaces of the extensive Roman iron-works in the neighbourhood of Epiacum (Lanchester). A part of the valley, rendered barren by the heaps of slightly-covered cinders, had never been cultivated till very recent times. 'During the operation of bringing this common into cultivation,' Mr Bruce says, 'the method adopted by the Romans of producing the blast necessary to smelt the metal was made apparent. Two tunnels had been formed in the side of a hill; they were wide at one extremity, but tapered off to a narrow bore at the other, where they met in a point. The mouths of the channels opened towards the west, from which quarter a prevalent wind blows in this valley, and sometimes with great violence. The blast received by them would, when the wind was high, be poured with considerable force and effect upon the smelting furnaces at the extremity of the tunnels.' This primitive mode of smelting is still in use among some peoples unacquainted with the improvements of civilized nations. The ancient Peruvians, for example, built their furnaces in this manner. Mungo Park also noticed a similar practice in Africa, and it has also been described as existing in the Himalaya mountains of Central Asia.

'The shoes of the first period are small, narrow, and scant of metal, constantly pierced with six holes, whose external opening is strongly stamped in a longitudinal form, to lodge the base of the nail-head. The slight thickness, and especially the narrowness of the metal, causes it at each hole to bulge, and to give a festooned appearance to the external border of the shoe. The thickness of the latter is from one-eighth to one-seventh of an inch, and the width from six to seven-tenths of an inch between each hole, thus indicating the dimensions of the bar of metal before stamping. The form of the stamped holes indicates the employment of a steel punch, and consequently a knowledge of the manufacture of steel at the period when these horse-shoes were made.

'One of these shoes (fig. 29) has been found, with a portion of the bones of a horse, in a peat-moss near the old abbey of Bellelay, at a depth of twelve feet, resting on the primitive soil. There was, therefore, every reason to believe that this horse had not been buried in the peat, but that, on the contrary, it had perished in this place before the formation of the heap, inasmuch as its scattered bones testified to the work of carnivorous animals gathered around their prey. Many of these shoes have been found at various depths in the turf-beds of the Helvetic plain, but we have not been able to obtain precise information with regard to them. This turf-pit has yielded numbers of coins from the first half of the 15th

fig. 29

century to the year 1480. These were only covered by 23½ inches of turf, still spongy, but which had nevertheless taken at least four centuries to form. Taking this particular case into consideration, and reckoning the overlying deposit as accumulating at the rate of 6 inches in a century,—far too low an estimate by reason of the density the turf assumes as it becomes old and forms the inferior layers,—the shoe discovered at the bottom ought to have lain there at least 2400 years. These same turf-beds enclose, or rather cover, a place where there is charcoal beneath 19 feet 8 inches of peat, and this being on the primitive ground, gives a period of more than 4000 years since it was laid there. In the neighbourhood there are iron scoriæ indicating an ancient forge, and in this country, where iron mines only exist, wood is carbonized for no other purpose than to work that metal, and all the ancient forges used nothing else.

'More than twenty of these shoes have been collected in the soil of a Celtic establishment between Delémont and Soyhiere, on the right bank of the Byrse, territory of Courroux, and near Vorbourg (fig. 51). There were no traces of Roman articles, nor yet those of a posterior age, but only antiquities of the stone, those of the bronze, and, lastly, of the iron periods. The last was characterized only by horse-shoes, and by two discs resembling the iron money of the Spartans. On the other bank of the river similar shoes were also found (figs. 30, 31, 32), and two beautiful lance-heads or Gaulish javelins. Near the first shoes was a pointed spur. Another shoe of the same form has been met with in the track of an antique road, near Saint-Braix, not far from one of those ancient forges where objects belonging to the stone age have been discovered, A neighbouring hamlet is called Césais or Cæsar, a characteristic name also given to a ridge or mound near which passes a Roman road joining the plateau of the Franches-Montagnes with the enclosure of Doubs, and which shows traces of military works. The Jurassian Society of Emulation is about to publish what we have written on the new discoveries made in this portion of our mountains (figs. 33, 34).

'Other shoes, always like the former, are frequently met with in pastures, forests, and cultivated lands, but constantly at somewhat considerable depths. They often also mark the ancient narrow road-ways, which have ruts worn into the rock, and where the short axle-tree has scraped away the stone at the sides in its passage, at a height of from 12 to 13 inches (Celtic roads). We have rarely found this description of shoes in the Roman camps; in fact, only on that of Mount Terrible, which was formed on an oppidum; we believe, however, that the shoes from this place belonged to the same category as the Celtic objects of the three ages, and which have been found in such large numbers. Nevertheless, it is very remarkable that one of these shoes has been gathered in the ruins of the castle of Asuel, supposed to have been built in the 11th century and destroyed in the 15th (fig. 33). But it might well belong to an earlier period, as we have found a similar specimen in the walls of the château of Sogron, where a horse certainly never planted foot (fig. 35). This building dated from the 8th century, and was burned in 1499; in its vicinity we have found a stone hatchet and two Celtic coins of Togirix.

'We might also mention the discovery of one of these shoes with undulated borders at a great depth near the glass-works of Moutier, on the track of a Celtic road at the entrance to the passes of Court, and also farther away at the level of the river Byrse (fig. 52). We have seen débris of shoes on the continuation of this road near the mill of the Roches de Courrendelin, and also near Grellingen, always beside deep ruts, and sometimes beside transverse grooves and cuttings in the rock, in the bed of these passages, intended to prevent the horses slipping. These same shoes are also found at the bottom of the tourbières of the Swiss plain, in the Gaulish monuments of Alesia, in the plains of Champagne, on the battle-field where Attila is said to have been defeated in 451.[10] The Cossacks, the descendants of the ancient Scythians, or Huns, yet shoe their horses in the same fashion. We might cite many other discoveries of these same shoes, as well in Switzerland as elsewhere, and particularly in the districts of the Jura. We think that these are assuredly the shoes of the indigenous horses which wandered or pastured on the mountains of our country, long before the arrival of the Romans; and they have remained in use with the Jurassic people during the Roman domination, and still later, concurrently with those we are about to describe. It may have happened that the shoeing of the Gallic horses was derived from the relations of the Gauls with Asia, where nail-shoeing is said to have been of high antiquity; and if we, as well as our neighbours, regard these small shoes as of Hunnic, Saracenic, or even of Swedish origin, it is simply because people confound the epochs of the invasions which have desolated the country. Even now, these articles are attributed to the Cossacks in 1814.

'In the numerous Roman camps whose remains occupy the summits of the mountains or hills of the Jura, along Upper Alsace, as in the chain of Lomont, in the castles of the same period, perched on culminating points, in the ruins of Roman villas buried beneath nearly every village, on the track of roads of the like date, and also scattered over the country, we have gathered horse-shoes of a different form to those already noticed, but whose dimensions yet resemble them, though they are always more circular. They are also stronger in metal, and consequently more heavy, varying from 180 to 245 grammes. They are with or without calkins (crampons), and pierced by six holes—three on each side, placed farther from the external border than in the preceding. The heads of the nails are still oblong, but not so high or salient, and indeed are nearly hidden in the holes counter-sunk for this purpose. There are other shoes which, in form, in weight, and in dimensions are allied to these, and are found in the same places; but they offer a characteristic difference. This consists in a groove (rainure, Angl. fullering) extending around the outer border of the shoe from the heels to the toe, and sometimes deep enough to completely lodge the heads of the six nails with which they are furnished. At other times, this groove is scarcely noticeable, and would appear only to have been used to indicate the line on which the farrier sought to make the holes. Shoes with a deep groove are yet in use in England; but with us they seem to have been older than, or contemporaneous with, the cutlasses with wide blades, sharpened only on one side, and provided with one or two of these longitudinal grooves. Knives of the same period are similarly ornamented, and these certainly belong to the end of the 4th or the commencement of the 5th century. The weight of these fullered shoes amounts to about 265 grammes each (about 91/2 ounces).

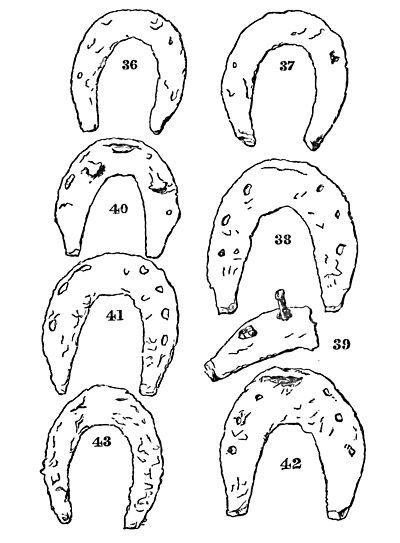

'These two varieties of shoes are not only met with in Roman establishments, civil and military, but also in the Burgundian tombs of the 5th century, and in ruins of the 7th and 8th centuries; as also in the dwellings of the middle ages, and in all the districts over which horses of this epoch have passed. According to all appearances, during the Roman period the people of the country had preserved the mode of shoeing practised by their ancestors of Celtic origin, and the breed of horses had scarcely increased in size; while the Romans, or rather the foreign troops attached to the legions, had imported stronger horses, and employed shoes different from those of our nation. Such is at least the opinion that we derive from the facts and the circumstances accompanying the discovery of these articles. We possess some shoes found with a heap of horses' bones, the hoofs of which yet remained shod, and which were lighted upon when repairing the road from Courtemantruy to Saint-Ursanne, not far from the Roman camps of Moron and Mount Terrible (figs. 36, 37). Another shoe, almost identical with them, has been gathered in the last-named camp, on the same level with Roman relics (fig. 38). A fragment was also found in the same place (fig. 39). The ruins of the Roman villas of Debilliers and Fourfaivre contained a considerable number of the type represented in figures 40 and 41. It would be superfluous to offer any more descriptions or drawings, because in nearly all the Roman sites in the country, shoes of the same, or of slightly different form have been collected.

It is at all times necessary to remember, however, that the majority of the Roman villas destroyed during the first invasion of the barbarians have been subsequently more or less repaired to serve as habitations, either by the Gallo-Romans, or by the Burgundians, when these last established themselves in the country. We have already given numerous proofs of these restorations of the 4th and 5th centuries by the Burgundians, and recovered many of the relics of these warriors of six feet in height, still armed with their grooved "scramasacs," the pointed spur at the heels, and wearing great girdle-plates of iron damascened with silver. One of these "six-feet" people of the 5th century was laid in a tomb formed of large masses of tuff roughly chiselled, and near him were found the bones of a horse, which had probably been that of the giant, the shoes of which yet existed; they had six oblong holes and were "fullered" (à rainures) (fig. 42). Not far from this many other graves, of the same or an earlier epoch, have furnished horse-shoes; the one we give a drawing of is the smallest, the others are wider in metal, so as to cover the greater part of the sole. This is not an exceptional form, for we have a number of the same kind. In addition, these shoes differ but little from those of the Roman period, and show a continuation of the same manner of shoeing, with the slight modifications the farriers adopted according to circumstances. There are always shoes with six nails, sometimes fullered, but not undulated as in the first period. In the foundation of the church of Moutiers-Grand-Val, built in the 7th century, a similar shoe has been found (fig. 40). To the shoes of certain origin, we add another form which has also been admitted at divers epochs, though more rarely, and appears to indicate a mode of shoeing strange to the country. We give as a type of these shoes (fig. 44) a specimen found on the track of the ancient road from Aventicum to Augusta Rauracorum by Pierre Pertius, and in the valleys of the Byrse, between Laufon and Bâle. They are particularly distinguished by the massive form of the calkins, which appear like a great protuberance a little in front of the extremities, which become sharp. The one represented is the thickest we have found; it was associated with more than twenty others mixed up with some Roman remains and coins of the 4th century.

This variety is found in the middle ages, in the ruins of various castles, as that of Sogron (fig, 45); a circumstance which leads us to think that they commence in the barbarian epoch, and continue during the middle ages, not regularly or as a generally adopted style, but rather as a foreign importation whose origin is unknown.

'Shoes really of the middle ages, and anterior to the 15th century, are characterized in those (figs. 45,46,47), from the Château of Sogron (8th to 15th century); and also those of Asuel and Vorbourg (figs. 48, 49), One of them is peculiar in having a very primitive toe-clip {pinçon), formed by the toe of the shoe being a little elongated and bent upwards (fig. 49); and another has the calkins inverted, or turning towards the heel of the foot (fig. 46). The specimen from Vorbourg (fig. 49) closely resembles that from Souboz (fig. 50); and yet the latter was found at such a great depth in a quarry, that the workmen believed the rock must have grown since it was deposited. But there can be little doubt that it was lost in the pasture on this part of the mountain traversed by a Roman road, and at a very remote date had slipped through a crevice in the rock.

'It has already been remarked that in the ruins of various castles, as elsewhere, shoes have been gathered like those of early times, but we have emitted doubts as to their employment at a later period. The shoe from the Château of Asuel weighs 425 grammes, and it has six nail-holes like those of the 12th century, mentioned in the Roman da Renard (edit. Willems, p. 241), when the cunning fox engaged the wolf Isangrin to read, under the feet of a mare, on what conditions she would surrender the flesh of her foal! This description of shoe, stronger in metal and of similar dimensions, appears to characterize the horses of the middle ages, which had to carry heavy caparisons of iron and riders covered with weighty armour. They sometimes offer an important indication, consisting in the mark of the farrier who forged them. This is very distinctly seen on the shoe from Asuel, and on those of Vorbourg and Sogron. That from Asuel reminds us of the time when the last owner of that place fought for Charles le Téméraire against the Swiss and their allies. The size of the shoes of these various epochs is not the only thing to consider in the determination of the species, for the dimensions must necessarily have varied a little. Nevertheless, it is very remarkable that those of the first period scarcely vary, and they might be confounded with the shoes of mules and asses found sometimes with the more noble steed. Certain small light shoes, bearing the characteristics just described for each epoch, may have belonged to some palfrey or hackney ridden by a young Gaul or Gallo-Roman, as well as to the steed of the fiery Châtelaine of the middle ages.

'This notice of the horse-shoes which have been worn in the Jura in ancient times is far from being complete; and it has no other merit than furnishing specimens of ascertained origin, and offering as closely as possible types rather than exceptions, for we have been careful to choose those for our drawings which represent the most characteristic and usual forms.'

In Belgium, shoes of this ancient type have also been discovered. In making a road at Jodoigne, in a cutting at a certain depth from the surface, some Roman pottery and four of these plates were discovered in a bronze vase. They were described by M. Schayes, who remarks: 'The horse-shoes were, like the pottery, in perfect preservation. I believe them to be of Roman origin. They are less regular in form than our modern shoes, and are no more than from 4 to 41/4 inches long, and 33/4 and 4 inches wide. The vessel containing these was supposed to be no older than the 15th century, and it was surmised that the articles had been put into it from some tomb and again buried. The previous year bones had been found in the place in which this collection was discovered.'[11] No drawings accompany the description.

In the Royal Museum of Antiquities at Brussels is a shoe, found in 1863, during excavations carried on at Wundrez-lez-Binche, Hainault. With it were several antiquities, and notably a bronze coin of Faustina (A.D. 175). Four inches in length and width, this specimen of farriery (fig. 53) has only four nail-holes, and though broad in the cover, is yet thin and light, and unprovided with calks. The outer border is even, the holes quadrilateral and well placed.

A very interesting discovery was made in 1848, during mining operations at Lede, a village near Alost, Eastern Flanders. Three shoes were found along with relics which authorities have stated to be Frankish, and to belong to about the 6th century. One of these relics is an earthenware vase (fig. 54), which certainly bears a striking likeness to one type

of that ware pertaining to that age and country. The first horse-shoe we might designate a Romano-Frankish specimen, from its resemblance to those we have named Gaulish and Gallo-Roman (fig.55). It has the usual irregular outer border, the six peculiar nail-sockets, only one calkin, and is light in form. It measures four inches in length and width.

The second example has a more modern appearance; has curiously shaped calkins on both heels, an even border, and six quadrilateral nail-holes. It is a little larger than the first specimen, and it will be seen from a side view that it bends up towards the heels of the foot (fig. 56). The third shoe is of the same width, but an inch longer than the last, and is particularly striking from its being coarsely grooved, having calkins which are strong exaggerations of those already described, and being greatly curved towards the heel and toe, so that the middie of the shoe is on the same level with the ground face of the calk (fig. 57).

In this respect it bears a marked resemblance to the ajusted shoe introduced by Bourgelat in the last century. It is somewhat remarkable to find these three types of shoes in the same place, along with Frankish remains, though neither of them differ from those described by M. Quiquerez. All these specimens are now in the Royal Museum of Antiquities, Arms, and Artillery, at Brussels, to the obliging curator of which I am indebted for information relative to them.

In Germany, we find the same traces of antique shoes as are discovered in France, Switzerland, and Belgium. The Germans, like the Celts, represent one of the most remarkable races of early times; and though their history does not extend so far back as that of the Celtæ, yet the ancient writers made very little distinction between them, and when they first encountered them found they were also in possession of iron. The Cimbri or Germans, then, wore mail armour, had polished white shields, two-edged javelins, and large iron swords. They were also to some extent a horse-loving people; and when they fought with Marius they numbered 15,000 cavalry magnificently mounted. Each had a fine lofty helmet, and bore upon it the head of some savage beast, with its mouth gaping wide; an iron cuirass covered his body, and he carried a long lance or halberd in his hand. The Teucteri, a tribe on the banks of the Rhine, were famous for the discipline of their cavalry. Their ancestors, in the early ages of tradition, established this force, and it was maintained by posterity. Horsemanship was the sport of their children, the emulation of their youth, and the exercise in which they persevered to old age. Horses were bequeathed along with the domestics, the household gods, and the rights of inheritance, and unlike other things, they did not go to the eldest, but to the bravest

and most warlike child.[12]

Their horses were neither remarkable for beauty or swiftness, nor were they taught the various evolutions practised by the Romans. The cavalry either bore straight before them, or wheeled once to the right in so compact a body that none were left behind. 'Who are braver than the Germans?' asks Seneca,[13] 'who more impetuous in the charge? who fonder of arms, in the use of which they are born and nourished, which are their only care? who more inured to hardships, insomuch that for the most part they provide no covering for their bodies—no retreat against the perpetual severity of the climate?' Cæsar tells us that they passed their whole lives in hunting and military exercises.[14] The chief's companions or select followers required from him 'the warlike steed and the bloody and conquering spear.' Their presents from neighbouring nations were most valued when they consisted of fine horses, heavy armour, rich housings, and gold chains.

The Suevi had, according to Cæsar, poor and ill-shaped horses. Yet they must have proved very efficient, for the Suevi, 'in cavalry actions, frequently leap from their horses and fight on foot, and train their horses to stand still in the very spot on which they leave them, to which they retreat with great activity when there is occasion; nor, according to their practice, is anything regarded as more unseemly or more unmanly than to use housings. Accordingly, they have the courage, though they be themselves but few, to advance against any number whatever of horse mounted with housings.'[15]

In the last century, shoes were dug out of graves, which were to all appearance pre-Roman. One of these shoes has been described as having the catches or calkins projecting in a peculiar manner upwards instead of downwards, as if to grasp the hoof; but it is not stated whether there were also nail-holes.[16]

Many years ago, veterinary surgeon Plank[17] mentioned finding shoes in Bavaria, which, from their antique form and the situation they occupied when discovered, he believed to have been worn by Roman cavalry horses. Schaum also speaks of ancient shoes as being found in his district.[18] At Willerode (Mansfelder Gebirgskreise), Rosenkranz[19] speaks of a variety of old iron work being found in grubbing up a forest called Wolfshagen. This consisted of rusty spikes, unusually large horse-shoes (ungewöhnlich grosse Hufeisen), a battle-axe, and a kind of sharp knife, made of flint, which he thought might be a sacrificial knife.

Klemm[20] remarks: 'The horse must have been equally valuable to the war-loving German as the intelligent and trusty hound was to the huntsman. The German horsemen were respected by the Romans. They displayed great affection for their steeds and had them under excellent control, although Tacitus does not praise the horses for either their beauty or speed. The Germans had saddles and horse-shoes; the latter are often found in the soil of the fatherland. They indicate a small race of horses then in existence. The horse-bones dug up by Dr Wagner were also small.'

Arnkiel,[21] speaking of the supposed horse-shoe found in Childeric's grave, notices that the most ancient shoes discovered 'are small and thin, very much oxydized, and have neither toe-pieces (griff) nor toe-clips, but small calkins at the heel, and the nail-holes are near the centre of the shoe.'

Ludwig Lindenschmidt,[22] who has so ably, and almost exhaustively, explored the ancient grave-mounds of Sigmaringen and its vicinity, is puzzled at the presence of single horse-shoes in graves, without the bones of horses, spurs, or equipment. 'They form one of the unsolved mysteries of the graves, and are in no way accounted for by the supposition that they may be intended as a sign of the former occupation of the deceased—as, for example, that of a smith. The Royal Museum contains several such single horse-shoes, discovered in graves, all of different kinds, and from different places. These objects buried in the tomb seem rather to bear some relation to symbols of old heathen superstitions—such as the practice of nailing a horse-shoe on the threshold of the door, which yet lingers in some places. Certainly the subject requires further investigation and explanation.' The very old grave-mounds of Gauselfingen yielded many primitive curiosities, such as celts, arm and finger-rings, glass beads, &c., of the Celtic or early German people. 'The third grave-mound contained two horse-shoes (figs. 58, 59), an iron arrow-head, a fine iron dagger, the handle of which was much damaged. Beside these lay the remains of a leathern girdle, ornamented with metal knobs.'

|

|

| fig. 58 | fig. 59 |

In the Grand-Duchy of Luxemberg, there are remains of what is known to archæologists as the Roman camp of Dalheim, which for many centuries have consisted in nothing more than substructures, though everything connected with them demonstrates that they constitute the débris of one of the most considerable establishments the Romans founded in this region. Many ancient thoroughfares, still known to the peasantry as pagan roads, abut on these ruins. The archæologists, from various proofs, but chiefly those derived from the presence of coins, attribute the final destruction of this important villa to the barbarian hordes under Attila, about A.D. 450. It has proved particularly rich in antiquities, which have been referred to the interval between Augustus and the fall of the Roman empire, and for many years excavations on its site have been carried out with great care.

In 1851, this camp commenced to be intersected by a new public road, and the excavations instituted by the Board of Public Works were placed under the direction and surveillance of the Archæological Society of the Grand-Duchy. Among other objects, evidently Roman, recovered from these remains, were four horse-shoes of a comparatively modern form—that is, more of the Burgundian than the Gaulish or Celtic shape. They were not all of the same dimensions. Figures 60 and 61, delineated by M. Fischer, a veterinary surgeon of Cessingen,[23] represent the smallest and largest of the four. The former is about the usual size of the early period to which they are supposed to belong, but the

latter is large. All had been worn, and bent nails yet remained in the holes. They were very much roded, and the two smallest were broken. The 'Burgundian' groove was present in the four specimens, and was continued from one extremity to the other. This mode of fullering is not now practised in this part of Europe. The least of these articles appears to have had six holes and no calkins; but M. Fischer represents the largest as furnished with nine apertures, and two square, wellformed calkins. M. Namur, the archæologist who described the antiquities found in the camp, asserts that they each had eight holes.[24] In 1852-3, the excavations being continued, a small shoe of the same shape was found, but it had only four nailholes;[25] and in 1854-5, the same antiquarian rescued several more, but they did not, it appears, differ from the others. M. Namur gives no drawings or descriptions of them, but merely states that they were of the ordinary form, and were found associated with Roman reliquæ of various kinds and dates.It may be noted that these specimens of antique shoes bear much resemblance to shoes found in various parts of Würtemberg, which Grosz figures, and which will be alluded to presently. He thought they belonged to the middle ages.

It is also somewhat remarkable, that at Steinfurt, in the same Duchy of Luxemberg, Engling [26] found two iron plates which had been horse-shoes, and he figures them among Roman urns and vases from this antique locality, believing them to be Roman. Each shoe possesses six nail-holes, and has the rainure circling from heel to heel. In shape they are not very unlike those from Dalheim (and which are now in the Archæological Museum of Luxemberg). They are described as so remarkably small that they were surmised to have been worn by mules; but, from their form, they were undoubtedly intended for the small indigenous horse (figs. 62, 63).

This grooved shoe is perfectly distinct from that of the Gauls or Celts, and is certainly a great advance in workmanship. The rough, bulging border gives place to an uniform one; and the groove, as well as the nail-holes and general form of the shoe, evidence skilful manufacture. From these discoveries, we are led to believe that the powerful equestrian nation of the Suevi, as well as the German tribe which in after-times constituted the Burgundi, shod their horses immediately after, if not before, the Christian era. How they acquired the art we know not; but it is well to remember that, in the 3rd century B.C., the Gauls passed along the line of the Danube as conquerors, and in their course left colonies among the Suevi, who, even in the time of Tacitus, still spoke the Gaulish tongue;[27] and also that it was often the Suevian cavalry, under Ariovistus, that the Sequani either fought with or against, in the wars between them and the Ædui or Romans.

Colonel Smith, in noticing the universality of horse-shoeing, says for Germany: 'We have seen it sculptured in bas-relief with a Runic inscription certainly as old as the 9th century, accompanying a figure of Ostar, upon a stone found on the Hohenstein, near the Druden altar in Westphalia, a place of Pagan worship that was destroyed by the Franks in the wars of Charlemagne. Had the horse-shoe been invented in that age, it could not already have become an object of mysterious adaptation in the religion of barbarians, which was on the wane at least a century earlier.'[28]

Grosz[29] mentions that, in the years 1730, 1744, 1761, and 1820, a somewhat large number of horse-shoes was found at certain places in Bavaria, during excavations. Some of them were very deeply buried, and thickly covered with rust. Though he does not altogether coincide in the views of several antiquarians as to the antiquity of these objects, yet his remarks are not without interest, particularly as he describes the different varieties which have been noted in Germany. 'The horse-shoes which have come down to us from remote periods, having been found in several parts of the country at various depths, show in general three essential varieties.

'The most numerous is that shown in figure 64.

At the toe it is more than twice as broad as at the heel, but it is thinner throughout than a German shoe of now-a-days. All shoes of this kind are furnished with calks at the heels, and sometimes at the toes, some of which have been welded on after the shoe was made, and others formed from the shoe itself. The greater number have a groove, in which there are generally eight nail-holes. The seat of the shoe is flat. The heads of the nails are sometimes narrow and sometimes broad, and project beyond the shoe. This variety of shoe is of several sizes, and no difference can be perceived between those of the fore and hind feet. According to tradition, it has been assumed that these broad shoes dug up in certain places were brought into the country by foreign armies, particularly by the Swedes (1632-48); but if one considers that not quite a hundred years ago there were no high roads in the country, and that horses were used mostly on badly-constructed paths, it is then probable that with us such a broad shoe was customary and necessary for special protection to the hoof. Still less should it be assumed that these shoes, as some would wish us to believe, were introduced by Roman armies; for the Romans have been expelled Germany since the 3rd century, and it might well be asked whether iron would remain so long in the ground (1500 years) without becoming entirely destroyed by rust. . . . Shoes of the second type, as shown in figure 65, are not unfrequently found in the neighbourhood of Stuttgart. They are of medium size, broad at the toe, with six or eight nail-holes, and partly grooved for the nail-holes. The sole is in some instances a little hollowed out towards the inner circumference; the calks are high, square, and placed towards the ends of the branches, something like slipper-heels (Pantoffelstollen), cut off obliquely, and in some very much prolonged. Some of these shoes have only one calk (a), which is long and pointed, while the other heel of the shoe (b), has merely an edge bent downward to match it. This shoe has a seat (richtung, curve to fit the foot) quite peculiar, the heel extremity being quite thin and tapering, and curving up towards the back part of the foot (fig. 66, a).

The Oriental and Arab shoes have the same bend given to them even in the present day. Since these articles correspond with the description of Spanish shoes both in their form and curve, and since Stuttgart was alternately besieged and occupied by the Spaniards in the years 1546 to 1551, and in 1638, it may be assumed with reasonable certainty that they are of Spanish origin.' 'Figure 67 exemplifies a form of shoe of somewhat rarer occurrence.

The specimens found are generally small, certainly never larger than middle size; they are narrow throughout, some being grooved and furnished with six or eight nail-holes; opposite to which the outside edge bulges a little. Instead of having calks, the heel-ends of the shoes become gradually narrower and thicker towards the extremities. The nail-heads are wedge or chisel-shaped, and project beyond the face of the shoe. Judging from the size and shape of these objects, and from the character of the nail-heads, they appear to have served as winter shoes for riding-horses, and without doubt were introduced by foreign cavalry. (From the end of the 13th to the close of the 18th century, Stuttgart and its vicinity was often visited by foreign troops, such as Imperialists, French, Spaniards, and Swedes.) These shoes are so oxidized and incrusted that they may well be looked upon as several hundred years old.

'Besides the horse-shoes just described, antique shoes of peculiar shapes and different construction have been found here and there in several places in and outside Würtemberg; so that it is evident that at the period to which they belong, the art of, shoeing was in a very primitive condition. Some few examples are provided with a groove, while others have long quadrangular nail-holes, often with oval countersinking; some, again, are furnished with heel and toe calks of unusual shape, others are plane, but, at the same time, as a rule, they are of exceedingly coarse workmanship: a fact which may still be perceived despite the ravages made by rust. . . . . Universal as the practice of shoeing is at the present day, there are yet places, such as North Germany, Hungary, and others, where it is not always necessary, and where horses are seldom shod, except on the fore-feet, or only in winter; others, on the contrary, as the horses of the rich, being shod merely as a kind of luxury on all four feet.'

The 'ajusted' or curved antique shoes are peculiar to Germany, it would appear. They have not been found in France, so far as I am aware; neither, as we will see hereafter, have they been met with in this country. It will be remembered that two specimens were found in Belgium. They seem to be generally grooved, and have peculiar calkins. Grosz's last illustration gives us the primitive undulating-bordered shoe.

We have seen from M. Quiquerez's report, that the earliest traces of grooved or 'fullered' shoes are found with remains of the Burgundi, and constitute a new and characteristic form. This ancient people—one of the principal branches of the Vandals, originally inhabiting the country between the Oder and Vistula—have left numerous traces of their passage through, and sojourn in, various regions of Switzerland and Gaul in the 4th and subsequent centuries. They established themselves to the west of the Jura, about the same time that the Goths entered Aquitaine,[30] and appear to have been, from the remotest times, distinguished from the other German tribes by living together in villages or burgen (from whence their name); which caused them to be looked down upon by the Teutonic race, and accused of degeneracy, in leading a life more adapted for the business of blacksmith or carpenter than that of a soldier. Sidonius Apollinaris, nevertheless, speaks of them as an army of giants;[31] and it appears certain that they were not only good artisans, but also brave warriors, in the intervals of peace earning a sufficient livelihood by their handicrafts; and that at the period of their residence among the ruined Gallo-Roman villas they shod their horses' feet with iron shoes. The discovery, in the tombs of these warriors, of the 'scramasax'—a large cutlass, sharpened only on one edge, and a characteristic weapon of the ancient Germans, with knives belonging to the same period (between the 4th and 5th centuries), all having long deep grooves on both sides corresponding with that in their horse-shoes—indicates that with the Burgundians, as with the Gauls and Celts, the same individual was at once armourer and farrier. The earliest tradition we have of this people, and which belongs to the period preceding their invasion of Gaul, would lead us to believe that they were skilled horsemen and workers in metals. 'The dwarf Regin fled from the Burgundians to the court of the Frankish king Hialprek (Chilpéric), who reigned on the banks of the Rhine, and there he undertook the duties of 'maréchal' (master of the horse and farrier). At this time he met the young Sigurd, son of King Sigmund, a descendant of Odin, who had miraculously escaped from the murderers of his father. The dwarf directed the education of this prince, and spoke to him of the wonderful treasure of the Nibelungen, raising in him the desire to carry it off to Tafnir. He forged for him the sword 'Gram,' the blade of which was so sharp, that, when plunged in the Rhine, it cut in two a lock of wool carried against it by the current. He also attended to the incomparable steed 'Grani.'[32] This skill in fabricating arms, and in the management of the horse, appears to have been a particular feature in the history of this people. In the middle ages, so highly were the services of the farrier esteemed, that at the court of the Dukes of Burgundy, on Saint Eloy's day, a piece of silver plate was given to the individual who shod the ducal horses.[33]

St Eloy, Eligius, or Euloge, was Bishop of Noyon in the 7th or 8th century, and by some means or other became the patron saint of farriers, and a gentle name to swear by in the days of Chaucer, who, in his 'Canterbury Pilgrims,' speaks of the 'Nonne'

'That of hir smiling was full simple and coy;

Hir greatest othe n'as but by Seint Eloy.'

The prioress's very tender oath, which custom of swearing was not at all an indelicate one for ladies, even for some centuries after Chaucer's time, has excited much contention among the commentators of the old poet. Warton declares that St Loy (the form in which the word appears in all the manuscripts) means, St Lewis: but in Sir David Lyndesay's writings St Eloy appears as an independent personage, in connection with horses or horsemanship, in the way he occurs in the above and other traditions relating to horses or farriery. Lyndesay says:

'Saint Eloy, he doth stoutly stand,

Ane new horseshoe in his hand.'

And again:

'Some makis offering to Saint Eloy,

That he their horse may well convoy.'

Horsemen also appear to have sworn by the good bishop; for Chaucer makes the carter in the 'Friar's Tale,' when he had been assisted out of the mud into which his horses and cart had stuck fast, to thank his assistants by the best animal in his team, and to exclaim:

'That was well twight (pulled) my owen Liard boy,

I pray God save thy body, and Saint Eloy.'

The saint was supposed to work great miracles among diseased animals. We will have more to say about him, however, at a later period.

So far as I am able to ascertain, we have no written evidence to show that the Germans shod their horses before A.D. 1185. According to Anton,[34] about that time mention is made of the shoeing of two horses (II. equorum ferramenta, Kindliger). In some old German records, given on the authority of Shopflin, there is a notice that the smith was obliged to deliver sixteen horse-shoes and the necessary nails. And in another writing (Sachsen Spiegel), it is ordered that 'the horses of messengers (die Pferde der Boten) shall only be shod on the fore-feet.'

Grosz[35] says that the shoeing of two horses is noticed in a Westphalian record of 1085.

In the year 1336, we find the Abbot of Waltersdorf, in Bavaria, making the following contract with his smith concerning the work to be accomplished, and its payment. 'He (the smith) is to make for his (the Abbot's) riding-horse three new steeled shoes (gestaehlte eisen) for two pence; and to repair three old ones for one penny. For two or three nails to fasten them, he is to receive nothing . . . . . and the work above stated is to be done with the Abbot's iron,' &c.

In 1400, a tax was fixed at Stuttgard for smith's work, and among other items, '6 heller (halfpennies or farthings) was to be paid for forging a new shoe.'[36]

Horses appear to have been early employed by the Germans to draw carriages or carry litters, for it is recorded that in the campaign of Arnulph or Arnold, Emperor of Germany, in Upper Italy, in 896, when returning across the Alps, a disease broke out among his horses which was so fatal, that, 'contrary to custom, oxen were employed to draw the litters instead.'[37] The use of horses in draught or carriage would have been very limited for Alpine travelling had they not been shod.

In Germany, as elsewhere at this early period, the blacksmith held a good position, if we may judge by the price of his wehr-geld, or 'blood-money.' The law of Gondebaud or Gombette, the most ancient of the barbarian codes, makes it manifest that the life of a smith was valued at five times the amount of a labourer or shepherd, and equal to that for the murder of a Roman slave belonging to the king.[38] The German and Salic laws also show that the duty of the 'maréchal' or 'mariscalcus' was to attend to twelve horses. 'Si mariscalcus, qui super xii. caballos est, occiditur,' &c.[39]

From the Rhenish provinces as far as Russia, what is termed the German shoe is in use. This is the model figured by Quiquerez, and which is flat on both sides, and with the fuller or groove for the nail-heads so far from the edge of the shoe, as to make the nail-holes very coarse. Immense calkins, and even toe-pieces of various shapes, are as much in vogue with the Germans as they are with the waggoners of Manchester, Liverpool, and other large cities in England and Scotland.

The Dutch and Russian shoes are coarse imitations of the German ones.

For Scandinavia, I am not aware of any discoveries which would show that this handicraft was practised at a very early period. If we are to give credence to the historians, archæologists, and anthropologists of that country, the Celtæ inhabited this region of the north; and if they did so, they doubtless preserved the same arts and usages as their nation in other parts of Europe. The 'Duergars' were their traditional workers in metals; and these fabricated steel and iron implements in secret caves. I can find but little mention of shoes, however, though doubtless these cunning workmen armed the hoofs as well as the bodies of the warriors, who were essentially an equestrian race.

The high antiquity of the iron-worker's art is made apparent in the Voluspa, a poem containing the oldest traditions of the Northmen yet discovered, and which is an outline of the earliest Northern mythology. We are told how—

The Asæ met on the fields of Ida,

And framed their images and temples.

They placed their furnaces. They created money.

They made tongs and iron tools.

At a later period, to be a proficient in metallurgical operations was the ambition of princes. Harold, for example, in the poem entitled his 'Complaint,' when describing his address as a warrior, relates: 'I am master of nine accomplishments. I play at chess; I know how to engrave Runic letters; I am apt at my book, and I know to handle the tools of a smith; I traverse the snow on skates of wood; I excel in shooting with the bow, and in managing the oar; I sing to the harp, and compose verses.'[40]

From the Sagas and the history of this region, it is evident that in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark horses were shod at an early period. At first only the rich and noble, perhaps, resorted to the use of shoes for their steeds, and some of these only for display, others when they had to travel on hard roads or during frosty weather. When used for agriculture, the horses may have been deprived of these defences.

Col. Smith states that horse-shoes were in use in Sweden before the Norman conquest of England, since the figure of one is struck on a Swedish coin without inscription, and therefore older than the use of Runic letters on medals.

In the eleventh century, shoes appear to have been in general use, for it is recorded that Oluf Kyrre, the first Norwegian king, caused those who sought his court to shoe their horses with golden shoes.

Recent discoveries in the peat-mosses of Thorsbjerg and Nydam in Sleswig have exposed remains of men and horses, supposed to have found their way there in the 'early iron period of the third and fourth centuries;' but no shoes were found, though there were bridles, spurs, and nose-pieces to protect the horse's nose. Skulls and bones of horses, sometimes almost complete skeletons, were noted, and the state in which they were found is curious. 'Near a tolerably complete skeleton of a horse, were found, besides shield-boards, shafts of lances, and other wooden objects, several beads, two iron bits, several metal mountings for shields, an iron spear-head, a whetstone, several arrow-heads, an awl of iron, and a Roman silver denarius. Not far from it were two skulls and other remains of horses, and near them some iron-bits. The skulls of horses, which, just as those last mentioned, appeared to have been deposited without the other parts of the animals, had still their bits in their mouths, one of the bits being incomplete and evidently deposited in that state. And if there could still be any doubt as to the skeletons being contemporaneous with the antiquities, it must yield to the fact that several of the skulls have been exposed to a similarly violent and inexplicable ill-treatment as the vast majority of the other objects deposited.' The bones were examined by Professor Steenstrap, the Director of the Museum of Natural History of Copenhagen, who pronounced them to have been the remains of three stallions of middle size. But the strangest thing is, that the skulls show the marks of heavy sword-cuts, which we are told could not have been inflicted while the animal was alive. Other portions showed that the horses had been pierced with arrows and javelins, while some of the bones had been gnawed by wolves or large dogs. There is here clearly something more than the mere death of the horse in battle. The enemy in such a case would never have taken the trouble to hew away at the skull, 'lying,' we are told, 'on the ground before him,' and that. Professor Steenstrap is inclined to think, when the lower jaw had been separated from the upper, and when the bones were no longer covered with flesh. All this leads us irresistibly to think of some sacrificial ceremony, and of the famous proscription of horse-flesh by the Christian missionaries. Horse-flesh must have been held to be an unchristian diet only because it was in some way connected with the idolatrous worship of the Northmen; the Mosaic prohibition could not have been urged by men who doubtless ate hogs, hares, and eels, without scruple. But then Professor Steenstrap tells us, that no 'such marks have been discovered on the horse-bones from Nydam as could indicate a severance of the limbs, or that the flesh had been eaten."[41] These appear to have been war-horses, and possibly at this time shoes may not have been worn at all frequently. We have seen that in France and Germany, long after shoeing was known, it was not universally practised.

- ↑ Troyon. Colline de Sacrifices de Chavannes-sur-le-Veyron, p. 5.

- ↑ Rapport sur les Collect. d'Antiq. du Musée Cantonal à Lausanne, 1858.

- ↑ Colline de Sacrifices, p. 12.

- ↑ Recueil d'Antiq. Suisses.

- ↑ Bieler. Journal de Méd. Vét. de Lyon, vol. xiii. p. 246.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Jahn. Antiquarisch Gesellschaft. Zurich, 1850.

- ↑ Les Anciens Fers de Chevaux dans le Jura. Mém, de la Soc. d'Emulation du Doubs, 1864, p. 129.

- ↑ The gramme is equal to 15.4 grains troy, or 16.9 grains avoirdupois.

- ↑ Camu-Chardon. Notice sur la Défaite d'Attila, Mém. de la Soc. Acad, de l'Aube, 1854.

- ↑ Bulletin de l'Académic des Sciences de Belgique, vol. xiii. p. 193.

- ↑ Tacitus, cap. 32.

- ↑ On Anger, i. 11.

- ↑ Bell. Gall. vi. 21.

- ↑ Bell. Gal. iv. 2.

- ↑ Bechmann. Beschreibung der Mark Brandenburgh. Berlin, 1751. Arnkiel. Heidnische Alterthümer.

- ↑ Veterinärtopographie von Baiern, p. 18.

- ↑ Alterith. S. von Brauenfels, S. 39.

- ↑ Neue Zeitschrift. Halle, 1832. Band 1. Heft 2.

- ↑ Handbuch der Germanischen Alterthumskunde, p. 133. Dresden, 1836.

- ↑ Cimb. Heidenrel. p. 164.

I much regret that I have been unable to refer to a paper by S. D. Schmidt on what were called Swedish horse-shoes: 'Ueber Sogenannte Schwedenhufeisen, mit Nachtr. v. Prof. Renner,' in Jena Variscia, ill. 61. - ↑ Die Vaterländischeu Alterthümer der Fiirstlich Hohenzoller'schen Sammlungen zu Sigmaringen. Mainz, 1860.

- ↑ Annales de Méd. Vétérinaire, p. 28. Bruxelles, 1853.

- ↑ Publications de la Soc. pour la Recherche et la Conservation de Monuments, etc., vol. vii. p. 185. Luxembourg, 1852.

- ↑ Ibid. vol. ix.

- ↑ Le Tombeau de Childeric I., p. 158.

- ↑ Tacitus, lib. xliii.

- ↑ Op. cit., p. 131. The horse-shoe arch occurs frequently as a figure on the sculptured stones left by the Celts, and which are found in England, Scotland, and elsewhere.

- ↑ Lehr- und Handbuch der Hufbeschlagskunst. Stuttgart, 1861.

- ↑ Aug. Thierry. Lettres sur l'Hist. de France, vi.

- ↑ Carmen xii. apud Scrip. Franc, i. 811.

- ↑ A. Reville. Etude sur l'Epopée des Nibelungen.

- ↑ E. Houel. Hist, du Cheval chez tous les Peuples.

- ↑ Geschichte der Teutschen Landwirthschaft von den Ältesten Zeiten bis zu Ende des Funfzehnten Jahrhunderts, p. 37. Gorlitz,1802.

- ↑ Op. cit., p. 8.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 9.

- ↑ Annales Fuldens. Pertz M., i. p. 411.

- ↑ Martin. Op. cit., i. p. 437.

- ↑ Lex Alemannor. Lex Salica.

- ↑ Mallet. Introduction à l'Histoire de Danemarc. London, 1770.

- ↑ Denmark in the Early Iron Age, by Conrad Engelheart.—Saturday Review, Oct. 13, 1866.